The Brain and Language

184.7k views804 WordsCopy TextShare

Professor Dave Explains

The way that humans communicate is very complex. We have an innate ability to understand and formula...

Video Transcript:

Professor Dave again, let’s learn about language. We just learned about brain lateralization, or the notion that certain cognitive functions can be localized more specifically in one hemisphere of the brain over the other. Language is one such function, as it is highly localized in the left hemisphere.

Attempts to understand why this is the case can help us understand the evolution of cerebral lateralization in general, so let’s take a look at how the brain processes language. The motor theory of lateralization proposes that the left hemisphere controls fine movements, speech being one of these, but our ability to make a variety of noises with our mouths is far from the full story when it comes to language. Unlike other animals, we are able to take a finite set of elements, which comprise some alphabet, and use them to express any idea imaginable, new or old, concrete or abstract.

Even monkeys and whales and dolphins, which do exhibit rudimentary forms of speech, can’t do what we do. They do not have such fine motor control over speech so as to produce the distinct syllables that we can. But they are also not as hard-wired as we are to be able to perceive and comprehend these sounds, something that is innate in humans, which are able to learn their parents’ languages remarkably quickly in infancy.

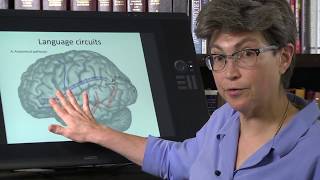

What are the specific areas of the brain that are responsible for this capacity? Two critical regions are called Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. The first of these is responsible for the motor functions that allow us to formulate syllables with our mouths, since damage to this area results in impairment of this function, without affecting the ability to understand language.

The second area is the one that is responsible for the understanding of language, since damage to this region does not impair the ability to vocalize, but results in complete nonsense being spoken. These two regions together with the basal nuclei form a language implementation system that analyzes words that are heard and produces our own speech in response. A surrounding set of cortical areas links this system with other regions of the cortex that are responsible for conceptualization of ideas, essentially enabling us to communicate our thoughts.

This highlights the features of language that are lateralized, though there are functions of the opposing hemisphere that are also relevant, which allow us to interpret the nonverbal components of language, such as body language, gestures, and any kind of tone or quality that would signify the emotional content of what is heard. Much of what we have mentioned so far can be considered part of the Wernicke-Geschwind model. This is comprised of seven components, two of which are Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, which we just discussed.

The others are the primary visual cortex, angular gyrus, primary auditory cortex, arcuate fasciculus, and the primary motor cortex. All of these are in the left hemisphere of the brain, not surprisingly. Now let’s trace the brain activity that occurs during a conversation.

According to this model, when you are listening to someone talk, their voice is converted into signals that are sent to the primary auditory cortex, and then conducted to Wernicke’s area. This is where we can imagine that the words are actually comprehended, as this is where the neural representation of the thought underlying the reply is generated, which is then sent via the arcuate fasciculus over to Broca’s area. From there, information is sent to the primary motor cortex, which controls the muscles in your mouth so that you may respond.

Instead, when reading aloud, the visual information of the written words is sent to the primary visual cortex, and this information is transmitted to the angular gyrus, which translates the written word into the corresponding auditory signal, and sends that to Wernicke’s area for comprehension. The rest follows the same path already outlined. We should note that this is simply a model, and is likely somewhat of an oversimplification of brain function.

There is empirical evidence to support this model, relating to patients with brain injuries in specific areas, and the observation of the type and severity of function loss. But the model is not flawless, it can’t account for all of the data, and not all of its predictions have been confirmed. But it is a reasonable model that serves as a basic understanding of how the brain perceives and produces language.

There is plenty more to discuss here, and it is up for debate the degree to which we are innately programmed to learn language, with syntactical and grammatical rules fully formed in the brain, according to Noam Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar. We will touch on this again in a future linguistics course, but for now let’s now move on to some other topics.

Related Videos

13:56

The Brain

Bozeman Science

6,031,941 views

34:33

The Tale of Trump and the Woke Trans Mice

Professor Dave Explains

193,170 views

12:16

What textbooks get wrong about language an...

Language of Mind

3,075 views

5:41

Psycholinguistics: Language and the Brain

Evan Ashworth

46,790 views

22:59

The Dome Paradox: A Loophole in Newton's Laws

Up and Atom

1,932,648 views

6:11

Language and the brain: Aphasia and split-...

khanacademymedicine

456,189 views

9:35

Elon gets NIGHTMARE news about Tesla

Brian Tyler Cohen

732,590 views

4:54

How do our brains process speech? - Gareth...

TED-Ed

423,226 views

18:54

Can You Fool A Self Driving Car?

Mark Rober

4,586,181 views

21:45

Is English really a Germanic language?

RobWords

573,429 views

18:35

Your Brain on Birth Control - Dr. Sarah Hill

After Skool

241,991 views

10:19

Au Revoir, Champagne | EPA Is Abandoning T...

The Late Show with Stephen Colbert

2,404,805 views

6:07

Brain Lateralization: The Split Brain

Professor Dave Explains

278,927 views

14:13

How language shapes the way we think | Ler...

TED

13,593,609 views

8:46

What happens to your brain as you age

The Economist

955,889 views

22:27

I Rode the Weirdest Trains in Japan

Ryan Trahan

1,654,828 views

14:27

The Biggest Myth In Education

Veritasium

14,390,463 views

12:14

11.15 Language Comprehension and Production

UChicago Online

27,127 views

5:52

The Neuroscience of Language

Neuro Transmissions

106,460 views

20:33

He Learned an Ancient Language Experts Cou...

Olly Richards

1,856,446 views