Aprende TODO Descartes FÁCIL y SENCILLO 😎 (en 15 Minutos) | Filosofía Moderna

1.37M views2722 WordsCopy TextShare

Adictos a la Filosofía

😬 ¡Hoy te traigo TODO el pensamiento de Descartes (padre de la filosofía moderna) en solo 15 minut...

Video Transcript:

¡Hello, philoaddicts! Today I bring you a very summarized summary of René Descartes' philosophy. I've wanted to bring Descartes to this channel for a long time, because truth is I've got a lot of objections for him, but today I'm bringing you just a summary of his thought that can be very useful to those of you who don't know him at all or to those of you who are preparing your Philosophy exams.

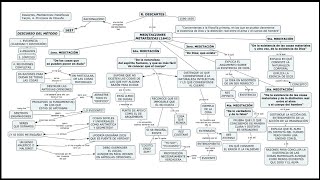

So, if you want to grab a pen and some paper, go ahead! I'll leave you too in the description a little scheme that can be of use in order to organize your ideas. So that's it, lets cut to the point!

René Descartes, father of modern philosophy, all of his thought is marked by the ceaseless search for certainty. This is a key idea: the criteria of truth for Descartes is certainty, subjective conviction. That is so that, if there is something of which I can have the most minimal doubt, the best we can do is to reject it and treat it as false.

In this point, Descartes is very influenced by the splendour of the new scientific method and, in special, by the strictness of mathematics, which give us exact, precise and doubtless results. On the contrary, he is very much disappointed with philosophers, who never manage to agree on nothing, with the result that philosophy does not progress and always stands on the same spot. Because of this he proposes that philosophy needs to change its method, and adopt a method that is equally rigorous as that of mathematics.

And in this new method of knowledge, doubt begins to take a very important role. Only doubting everything, at least once a lifetime (he says), one can reach some truth. Only through doubt as a method we can establish the doubtless bases of philosophy's building, and ground knowledge in a solid and secure manner.

Doubt, curious enough, has become a method, a path to certainty. This method will have four rules: First, the rule of certainty: never accept nothing as true unless I am completely convinced of it. In the end, this is about avoiding judgment rashness until I get certainty.

The criteria of truth is certainty or, as Descartes puts it, "clarity and distinction". Therefore, it is about searching ideas that are clear and distinct. Second, the rule of analysis.

One should divide problems in as many parts as possible and necessary. Divide that which is complex into that which is simple in order to arrive to those basic ideas that are clear and distinct and that can be nothing else but true. Third, the rule of synthesis.

Once I've arrived to the most simple, I need to conduct my thought with order and keep ascending until I reach that which is complex. This way we translate the certainty of simple ideas (clear and distinct ideas) up until complex ones, through careful logic and rational steps, with the aim of clarifying complex ideas and making them evident. Fourth, the rule of enumeration.

Repeting and reviewing all steps that have been done until I am completely sure that I've left nothing out. So be it, let's repeat these four rules, again and again. .

. Just kidding, if you want to rewatch it, go back and do it. We'll keep going.

Descartes' most important text is his Six Metaphysic Meditations, where he employs, step by step, this new method of knowledge. In the first meditation, Descartes aims at doubting all his ancient opinions and starting absolutely from zero until he finds a truth beyond doubt on which to base all knowledge. With this in mind, he departs from the world and from everybody, he retreats to his room and handed himself over only to his thought.

By the way, in the original latin, "ancient opinions" reads as "vetus opinio". I say it because if you write it on your exam, you're going to look pretty cool. In terms of results, the first meditation is a complete disaster.

Descartes does not find that which he was looking for, he does not find any undoubted truth. He starts doubting about our sensitive knowledge, and he realizes he can no longer trust his senses. His sense have deceived him already in the past, like when he puts a straight stick into water and it seems broken; or when he sees Peter in the distance, but when he gets closer it turns out he was Joana.

On the other hand, there's neither an absolutely infallible criteria by which to distinguish when I am dreaming from when I am awake, because certainly there are a lot of dreams that seem pretty real when I have them. So my senses don't pass the exam of the doubt and with them the whole world goes to the trash, because I can no longer be certain that the world my senses show to me trully exists. But at least one can be sure about mathematical truths, right?

I mean, 2 + 2 is always going to be 4. But Descartes says "Hmmm. .

. it might be that an evil genius exists who deceives me and makes me believe that 2 + 2 equals 4 when in fact they're 5". So I can neither be absolutely, absolutely, absolutely certain of mathematical truths.

If we were talking before about a methodical doubt, a doubt that's used as a method, now we're in front of something called hyperbolical doubt, because Descartes brings the doubt to its extreme, to its exaggeration. In short, at the end of this first meditation Descartes is not even sure that his mother loves him. Maybe that's why he got in this mess.

. . poor chap.

Never mind, let's move to the second meditation. Here, the great discovery is made: Descartes comes across a truth beyond doubt. Un-doub-ta-ble.

As much as there is an evil genius, he cannot deceive me about my doubt. That is, if I doubt, then I am certain that I doubt, nobody can deceive me of that. But there's more: if I doubt, that is because I think and, if I think I exist.

Cogito, sum. "I exist" stands as the first undoubted truth, the new philosophy's first principle. And I exist precisely as a thinking thing, as a "res cogitans".

. . or "res cogita" (one-legged cow, in Spanish) for his friends.

OK, fair enough, I exist but. . .

what am I? A thinking thing. This is important, ok?

For the moment, I am just a thinking thing. Because Descartes has thrown away the body with all the sensible world; I cannot be certain about the existence of my body. I am only certain that I exist as a thinking thing.

And here begins the radical distinction between soul, or "I", and body that will be the basis of cartesian dualism. More things, I exist, sure, but. .

. what about everybody else? Well, I don't know.

I just know, I am just sure that I exist. . .

if I think. At least when I think, of course. That's why I'm always telling you to exercise your mind, because if you don't then what happens is that you cease to exist, and that's something nobody wants.

If you exist, of course. . .

Now seriously, the intermittence of the cogito is a problem that Descartes does not solve yet, in this meditation, because the cogito only exists when it thinks. When it does not think. .

. I don't know whether it exists or not. Only when he proves, in the coming meditations, God's existence then he'll be able to affirm that I exist even when I don't think (when I'm asleep, for example), because God, who thinks me, maintains me, holds me, in existence.

In short, in the second meditation I find out that I exist, but I do not yet know whether something outside myself exists or not. That is, I am alone, radically alone. That's why we need to keep going.

Third meditation, Descartes looks inside his self and finds three kinds of ideas: Innate ideas, which are those I belive have been born with me; adventitious ideas, the ones that I belive come from outside, and factitious ideas, the ones I invent or build myself (like, for example, the idea of a centaur or a mermaid). From this basis he tries not one, but two arguments to prove the existence of God. The first argument goes like this: I find in me the idea of a perfect and infinite God, but this idea cannot come from me.

It cannot be factitious, I cannot have invented or built it because I'm just a finite substance. The idea of infinity could only have been put in me by an equally infinite substance. That is to say: GOD.

Therefore, God is the cause of the idea of infinity I find inside of me, and He has put it there as the artist signing his work. God is the only explanation for me, a finite substance, having in me an idea of infinity. The second argument says that I couldn't exist if God didn't exist.

Because I am an imperfect and finite substance, I have not created myself, and I am aware of not having existed always. Damn! I'm not even sure my existence goes on when I stop thinking!

Even more, if I were God, if I were perfect and infinite, I would not have the doubt. My knowledge would also be perfect. Therefore, somebody must have caused me, and that somebody, if we want to avoid a regression to infinity, must be God.

God is, then, not only the cause of the idea of infinity I have inside me, but also cause of me. God is the only explanation of my existence. This God that he is discovering is, also, perfect and, thus, totally good and cannot be a deceiver.

The fourth meditation is like a little bracket and Descartes uses it to explain how can it be that, if God is good, error exists. Descartes explains we have two faculties: intelligence and will; and that while intelligence is finite, will is, in exchange, infinite. So to speak, will is "larger" than intelligence.

Error, then, happens when my will wants to run faster than my intelligence and does not keep itself inside the limits established by intelligence. That is, it happens when I rush in judgement because my will wants to judge something NOW. If I see in the distance someone that looks like Peter but I'm not quite sure he is him, if I manage to contain my will until I'm completely sure, then I'll not take the disappointment of saying hello to Peter and realize he was actually Joana.

I had a very good teacher that explained this as follows: if intelligence is the sleeve and will is the arma, erro happens when you stretch more the arm than the sleeve. But this, says Descartes, has nothing to do with God being evil or inducing me into error. Instead, it is our will's fault, because it does not follow the limits put by our intelligence.

Also, God, who is good, has given me a method to avoid error, consisting in the four rules I've told you before. In the fifth meditation Descartes presents a third argument for God's existence. He hadn't enough with two.

. . This argument is called the "ontological argument", and it is as follows: Just as the idea of a mountain is inseparable of the idea of a valley, that is, just as I cannot think a mountain without a valley, or a triangle without three sides, the idea of God implies, necessarily, his own existence.

How is so? Because the idea of God is the idea of a extremely perfect God, and a God that didn't exist would be an imperfect God, because he would be lacking a perfection: existence. If one thinks it right, then, one cannot think God as non-existing, because the idea of God is inseparable of the idea of existence, just as the mountain is inseparable of the valley.

The essence of a extremely perfect being must have all perfections: among them, existence. I can think of a horse with wings or without them but, strictly speaking, I cannot think in God without existence, just as I cannot think in a triangle with four sides. The idea of God implies, necessarily, existence, and this God, who is perfect, cannot be deceiver because he is good.

The hypothesis of the evil genius, then, falls down, and I can rescue mathematical truths. Now I can be completely sure that 2 + 2 equals 4, because God, who exists, does not deceive me. Now that I know that God exists and He cannot deceive me, I can trust my knowledges.

Therefore, God becomes the guarantee of my knowledge. Lastly, let's check the sixth meditation, where Descartes recovers the sensible world. How does he do it?

Well, it's a little complex, but basically as follows: As he's proved that God exists and is not a deceiver, I can trust my senses as long as I use the method of the four rules seen before. It would be contrary to the divine goodness that the ideas I perceive as received from the outside world did not correspond with with nothing real outside of myself. Because I'm sure God does not deceive me, doubting about the existence of the external world and my body is exaggerated.

A curious idea that he enounces by the end of the sixth meditation is that, though I need to be careful with my judgements and not rush, in the essential I can trust what nature teaches me because nature, considered in general, is nothing else but God, and God does not deceive me. Where does Descartes get that nature is God? Well, a little from here, out of his sleeve.

But, anyway, the thing is in understanding that, though my senses have deceived me sometimes, well, error is not the common thing and, besides, I now have a method that, if followed strictly, helps me avoid any mistake. And so, because God does not deceive me, I can trust my knowledge. And that is how, in the end of all meditations, we have obtained three substances: the "res cogitans", which is me, the finite thinking substance; the "res infinita", which is God, the infinite substance; and he now has deduced the existence of the "res extensa", which is the material or extramental reality.

Exterior reality is left reduced, therefore, to extension, and this is going to give place to cartesian mechanicism, because a reality reduced to extension can only be understood in a mechanic manner. This piles up more difficulties to the relationship between soul and body, because Descartes is understanding them as two completely different substances. Then, how can it be explained that a wholly inmaterial and inextense substance can affect another substance that is purely extension?

Animals are also reduced to lifeless machines, in nothing different from a watch. But, however, let's leave objections for another day because we could be going all day like this. What do you think?

Does Descartes convince you? Do you buy his arguments for God's existence? How do you know you're awake and not in a dream?

How are you sure your mother loves you? And that's it, if you're sure you've liked the video, don't doubt it and hit the like button, share it with those friends of yours who may not exist and subscribe before the evil genius convinces you it's not worth it. And that would be it, I'm going to rest and stop thinking a little bit.

(P): Oh, my God! Where did he go? Has he ceased to exist?

! What am I going to do without him? !

But. . .

(P): Wait a minute. . .

Who am I talking to? Am I not alone in the universe? Am I not the only one that exists?

(P): Me and my ideas, and nothing else. I think because I exist and I exist because I think. But, if I cease to think.

. . (P): I cease to exist!

(P): Fine, Pikachu, don't stop thinking! Just think in nice stuff, like global power, like. .

. Pikachu, Pikachu, dude? Calm down, you, it's just an iMovie effect.

. . (P): Oh.

. . can you bring me water?

Related Videos

14:44

Dualismo vs Monismo

Filosofia Moderna

2,233 views

Binaural Beats | Boost Focus and Concentra...

Greenred Productions - Relaxing Music

16:34

Filosofía 2º de Bachillerato: DESCARTES (m...

Titi CLB

405,693 views

13:10

Por Qué la Ciencia NUNCA podrá explicar la...

Adictos a la Filosofía

142,291 views

1:06:37

video con todo leibniz para que impresione...

Adictos a la Filosofía

105,101 views

18:26

LA ÉTICA DE SPINOZA 😱 (FÁCIL en 20 Minuto...

Adictos a la Filosofía

191,242 views

16:37

Filosofia de DESCARTES (Català)

Lluna Pineda

514,263 views

7:42

Descartes (Primera parte)

Unboxing Philosophy

1,300,060 views

11:05

Descartes - La Primera Meditación explicada

La Travesía

82,975 views

10:05

DAVID HUME y la CRÍTICA a la SUSTANCIA 🤔►...

Adictos a la Filosofía

336,766 views

39:26

RENÉ DESCARTES - Meditaciones Metafísicas:...

Silvana de Robles

9,182 views

17:41

La Demostración Filosófica de la Vida Eter...

Adictos a la Filosofía

219,883 views

![5 Pasos Claves Para hacer de los Próximos 6 Meses el Mejor Cambio de Tu Vida [Dra Marian Rojas]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/MZUeBwrafx8/mqdefault.jpg)

15:46

5 Pasos Claves Para hacer de los Próximos ...

Mentes Ganadoras

20,625 views

20:20

INTRODUCCIÓN A LA FILOSOFÍA | Clase #9: Fi...

Filosofía en Red

111,359 views

10:30

El SUPERHOMBRE Para Que Lo Entiendas FÁCIL...

Adictos a la Filosofía

631,465 views

22:03

René Descartes para principiantes: “Pienso...

Filo News

146,150 views

1:31:48

Si Dios Existe, ¿Por qué Permite EL MAL? (...

Aladetres

384,508 views

11:41

Todas las Filosofías Explicadas en 12 Minutos

El Más Listo

229,459 views

15:05

KANT en 15 minutos (Explicación ANIMADA pu...

Filosofía en Minutos

1,883,251 views

18:50

El Misterio de la Conciencia 🤔► El Proble...

Adictos a la Filosofía

196,588 views