Here we are in the Faroes, a remote community up at the North Atlantic. We have been living on fishing for hundreds of years. We have no production of chemicals, but we are exposed to a lot of chemicals.

They came to us without asking us. We have seen negative effects on the health of our children. We want to see their development because we always have been a bit suspicious if these substances can have any impact on the endocrine system.

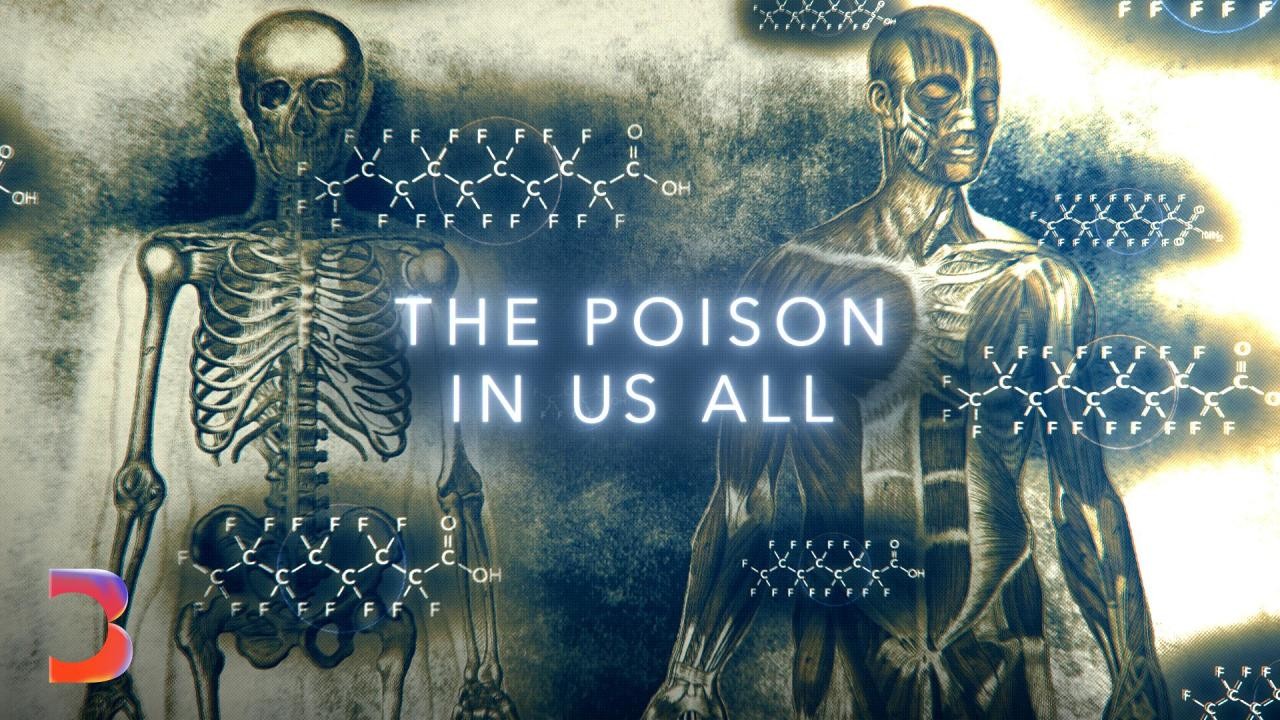

This is the price to pay for what the international society have done without thinking about the consequences of just releasing new substances. What we have seen here in the Faroes is that this is part of a absolutely global contamination that may have started in the 1960s, without us being aware of it. The PFAS is everywhere.

PFAS have contaminated our food supply, and PFAS can also accumulate in soils, in sediments. The chemists who have sampled rainwater on the Antarctica and in the Himalayas, what do they find in the rainwater? PFAS.

It's all over. They don't just stay in the environment, in our water, in our soil, but they get into living things, and they stay in us. It's like a ticking time bomb in the body, as this stuff is building up and coating all of our organs and staying there year after year.

We have analyzed thousands and thousands of human blood samples. We never met one that did not contain PFAS. We have all paid a high price due to large corporations carelessly dumping known toxic chemicals.

Through no fault of my own, I was exposed to these toxic chemicals, and as a result, I will die with this cancer. We've all been used as guinea pigs for the last 70 to 80 years. We weren't told we were being exposed, even though the companies knew that these things, if we put them into these products, they will get into people.

They will get into people's blood. But they did it anyway. It's hard to even talk to people about these chemicals and tell them, look, there's a chemical that's in you that's not found anywhere in nature.

These chemicals are found in 99% of people. It just sounds crazy. Tell people that these are also forever chemicals, that we've created a chemical that we don't know how to destroy, it sounds even stranger.

So PFAS are synthetic, man-made chemicals. PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. It's quite a mouthful.

It's an acronym that stands for a family of thousands of different chemicals. The most recent estimate from the EPA says that there are over 14,000 different chemical structures that they recognize to be PFAS. They share the same chemical property of having many carbon-fluorine bonds.

These carbon-fluorine bonds are some of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry. So for this reason, PFAS have also been called "forever chemicals," because those carbon-fluorine bonds just really don't break down. But the part where this story gets really strange is looking at their origins, because these chemicals came from the Manhattan Project, which was a secret project to build the atomic bomb in World War II.

So after the war, companies began experimenting with these chemicals. One company had a scientist who accidentally splashed some of it on their canvas shoes. They discovered the chemicals had stain-proof and water-proof properties.

That company was 3M. Because of their unique chemical properties, they're added to products to make them non-stick, greaseproof, stainproof, and water resistant. You know who's going to win this contest.

Teflon is so much easier to clean than stainless steel or uncoated aluminum. These chemicals went into some of these company's most famous products, like 3M's Scotchgard and DuPont's Teflon. These chemicals were really at the dawn of what we think of as the era of better living through chemistry, and they sort of epitomized this attitude of consumers and companies that everything we do could become more convenient.

. . .

on virtually any fabric! Use Scotchgard fabric protector and let your cup runneth over. And consumers are still really enjoying the fruits of this era.

When you look around you, there are so many things that are stainproof or waterproof, like pizza boxes that are grease-resistant or microwave popcorn bags. They're in industrial applications like plastics, semiconductors. They may even be used in solar panels and wind turbines.

They're in a lot of products that it's not even clear why they're there, like toilet paper or dental floss. But as time has gone on and more scientific research into them has progressed, we've realized that they also have a downside. We're east of Minneapolis in Minnesota, near 3M's global headquarters.

So back in 2018, I started looking at 3M's history with PFAS chemicals. I wrote a story at that time. A lot has changed since then and I'm back to see what's happened.

In 3M's hometown in Cottage Grove, Minnesota, and in these surrounding areas of Oakdale and Lake Elmo, the company had been dumping these chemicals since the 1960s. And clearly these chemicals got out into the environment, they were seeping underground, getting into aquifers, getting into soil, and that's really the beginning of this gigantic plume that was later documented around the 3M site in Cottage Grove. The pollution has caused concern among the people who live in the area.

There are troubling statistics about childhood cancer, which is thought to be more connected to environmental contaminants. Hi. Hi, how's it going?

Hi. How are those burgers? Great!

I'm a wonderful barbecuer, obviously. Do you have a plate to put them on? That probably would've been something I should have grabbed as well.

Oh my gosh, mother. I have the other. Back in 2018 I interviewed a number of local residents, including Amy and her daughter Lexi.

I was so happy to get back in touch with you and find out that Lexi has made a full recovery. So how many years did that take and- Being like, done with treatment and stuff to be fully like, considered cancer-free, it took five years after I was treated for it. So when did you first start suspecting that it could be an environmental issue?

I drank city water growing up, so City of Oakdale Water. And then when I was pregnant with Lexi, her dad and I moved into an apartment in Oakdale and lived there until she was about two or three and all of her baby bottles were made with the water. We didn't buy the filtered water then.

I don't think it was like, as common as it is now. Like, to me, I don't really remember people as having bottles of water. It was more of a luxury.

People didn't wanna spend money on that. I mean, do you ever think back about, like, eating fish from the lake or anything else that might've put her at higher risk? Yeah, so- I've been eating fish since like, the day I was like, one years old.

Like, since the day I could chew my grandpa has been having me eat fish. From the lakes around here? Yeah.

So my dad, her grandpa, he's a professional fishing guide. Oh wow. So he loves the fish, and he loves to go fishing and come home and make big fish fries.

And yeah, they live right over by here. It's about a six-minute drive from here. So all the lakes that he would go to would be Lake Demontreville, Lake Jane, all the ones in Lake Elmo.

My dad's a lot more particular now if he's gonna actually keep them. Not everyone was as fortunate as Lexi. Death records show a child who died in Oakdale from 2003 to 2015 was 171% more likely to have had cancer compared to those who lived outside the contaminated area.

So in that area, one of the schools was Tartan High School. And there was a math teacher there who told me the numbers just weren't adding up. There were so many students who seemed to have rare cancers, so many teachers who had family members with cancer.

And one of the most outspoken students about this was Amara Strande. I'm 20 years old, and at the age of 15, I was diagnosed with stage four fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. I've had over 20 surgeries, including two liver resections and one open chest surgery.

There are no more treatments to try, no roadmap, and no plan. So is this her bedroom- Bedroom. or just her hangout?

No, this is her bedroom. No, this was her bedroom. The reason why there's no bed in here is because it was a hospital bed, and we had to give that back to- The hospice.

It's from hospice. Yeah. Amara was diagnosed with cancer at age 15 and she died just two days before her 21st birthday in April of 2023.

What she's most proud of is- Her music studio. Her music studio. Wow, how many different instruments does she have in here?

I see a violin. There's a ukulele, her mandolin. There might be a harmonica or a kazoo somewhere in there.

Her first love was music. She was a composer. She had written songs.

Her dream of a career was to write music, compose music for either computer games or maybe even film scores. And she could keep composing even while she was sick? She was composing up until just a few days before she died.

Yeah. But she couldn't sing anymore. They removed this large mass that had grown into the fibers of her liver, of the fibrolamellar variety of liver cancer.

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is a cancer that is found in one in five million people. It's very rare. Did any doctors along the way say they thought there might be an environmental cause for the cancer or suggest any lifestyle changes?

That was not their concern. Their concern was to deal with the cancer as they understood it. It wasn't until much later that Amara started inquiring about, how possibly could this happen to her?

And did she first start asking those questions at all because she was a student at Tartan and there have been so many other cancers there? Absolutely. I mean, she was aware of the community concern about PFAS.

It was something that the kids talked about at school and even joked about, you know, as much as you can joke about, you know, "Don't drink the water here. " "Don't drink the cancer water. " Yeah.

As they talked about it. She knew kids whose parents had cancer, and then she knew kids whose siblings had cancer. She wanted to know, why doesn't anyone know about this?

Why aren't people asking questions? Even though Amara and Lexi's mother Amy believe that these cancers are linked to PFAS chemicals, it's something that's very hard to prove. It takes years of research both on a population level and in particular when you look at one individual.

But fears about the water intensified by what would come out in the 2010s. Minnesota sued 3M for damaging the state's natural resources with its dumping of PFAS, and in doing so, a mass of the company's internal documents were released. What they revealed has been described as a scientific cover up.

Seeing the documents that in 1975, 3M was told, we think we're finding your chemicals, these perfluorinated materials, in the blood of the general US population. And to see what was going on internally, you know, 3M started testing its own workers and found, yes, this chemical is building up in the workers who were exposed to this chemical. They were seeing studies of these chemicals on animals with disturbing effects.

It shows that in 1997, 3M gave DuPont a material safety data sheet with a label that said: "Cancer: Warning: contains a chemical which can cause cancer. " But 3M removed that label the same year and for decades sold PFAS without warning the public of its dangers. You see the companies internally debating.

Do we say anything? Do we tell the government? And unfortunately what they decided was, no.

Some of 3M's documents even showed that there had been a sort of whistleblower inside the company named Richard Purdy who had said the company wasn't telling its customers about the risks of these chemicals, and he resigned. He referred to 3M's PFOS, or P-F-O-S, as the most insidious pollutant since PCBs, Some of the most notorious PFAS are PFOS and PFOA. So these are two PFAS molecules that have a carbon backbone with eight carbon atoms.

These are the chemicals that so far have raised the greatest concern. These are the ones that show up most frequently in the environment. These are also the ones that show up most frequently in people's bodies.

They have half lives in blood of years, which means that it would take years to decades for the levels in your blood to go down to an unmeasurable level. The 3M company had actually had one of its own scientists sit down and calculate what would be a safe level in human blood, and that scientist had calculated, and they even used the word "safe" on the headline of the document, that the safe level for this chemical in human blood would be no more than 1. 05 parts per billion.

At the time, in the late 1990s, the average level of that chemical being found in the general US population's blood was 30 times higher than that. In 2018 3M settled, but there was no admission that it had done anything wrong, that there had been a scientific cover up, or what the real risk of these chemicals was. 3M will pay 850 million dollars to settle claims it contaminated water in Minnesota for decades.

It's hard to talk about in our community because, like, everyone loves 3M, right? There's not a person I know personally from 3M who isn't a stellar individual. I feel torn inside myself, but I am really angry at whoever, at whatever level did what they did, especially after they knew the chemicals were dangerous and they kept doing it.

So no one even knew what these chemicals were until this lawyer from Ohio came along. His name is Rob Bilott, and he took on the case of a farmer who had these cows downstream of a DuPont factory that were dying. It's unbelievable.

That calf has died miserable. And so Rob Bilott's story is now told in the film "Dark Waters," where he's played by Mark Ruffalo. DuPont is knowingly poisoning 70,000 local residents for the last 40 years.

That's not what I was trained to do. That wasn't the kind of thing I was normally doing at the time. I was actually working with chemical companies and big corporate clients, helping them navigate all the federal, state, international laws, rules, regulations, governing things going out into the environment.

It was actually through that case that we took on back in 1998 that we first found out that these manmade chemicals we now call PFAS, forever chemicals, even existed. What we're seeing is not only are we finding all these potential human health impacts, but we're seeing them happening at lower and lower dose levels and exposure levels. We recently had the Federal Environmental Protection Agency come out and essentially say, if you can detect this, it's of health concern.

The safety advisories keep getting lower and lower. From 70 parts per trillion for both PFOA and PFOS in drinking water in 2016, the EPA lowered it to just four parts per trillion each. That's less than a single drop in an Olympic-size swimming pool.

Each time those levels are lowered, it means that more people live in an area where contaminated water is thought to be a concern. A recent study found that as many as 200 million people are drinking water with more than the acceptable levels of PFAS. That's around two thirds of Americans.

States are taking action, and one of those states is Minnesota. They're not taking any chances with the PFAS that are in drinking water. And to do that, they're trying out new types of water filters.

PFAS is out in the environment, and it will spread as far as the water can spread it. It's left the barn, it's out of the gate. This waterway is carrying the PFAS right where the air meets the water, and these little bubbles are sort of signs that there might be PFAS in that water.

PFAS has a hydrophobic and a hydrophilic nature to it. So if you think about it as like a caterpillar, the head of the caterpillar is hydrophilic. It wants to be in the water.

And the tail of it wants to be out of the water, it's hydrophobic, so it kind of surfs along. And so it actually has that property that behaves the same way out in the environment on its own, or whether you're putting it in the water or on a pan, it's going to behave the same way. So Mother Nature is saying, here's your PFAS, it's in the foam.

And so we wanna take advantage of that and do the most removal we can. It's called the SAFF. It's surface activated foam fractionation.

We fill those full of contaminated water, and then we are able to physically remove the PFAS by foaming it, adding air into the system. And then we pull the PFAS off of that foam again, and that's where we get a small volume of very high-concentrated PFAS-containing liquid. Thus far, the test has shown us that we can remove roughly 92 to 98% of PFOA and PFOS.

It could run at least at 60,000 gallons of water treatment per day, and this is just one small system. So this is effectively the test to see whether we can scale this up to very large volumes and can we apply this in a permanent location to reduce the PFAS in the environment altogether. It's not just 3M or DuPont who are responsible for PFAS pollution.

There's about a dozen companies that have produced PFAS around the world. Highly concentrated levels have been found in Europe, Japan, and Australia. It's become a multi-billion dollar problem globally.

Like the US, a lot of these sites are places where the chemicals are manufactured, or sites where other companies use them. One of the most widespread sources are military bases and airports, where firefighting foams containing 3M's PFOS were sprayed right into the ground. We're just going right through here.

So you're here to have your blood drawn? Yes. All right, so come on with me here.

I've come to Mount Sinai Hospital in New York to have my blood taken and tested for a variety of PFAS. We'll give you a little warning there. Little jab.

All used in different products and made all over the world. So we know these chemicals are everywhere, and they're in everyone, and the question is obviously, you know, what level of them is unsafe? It's something that science is still trying to figure out.

Personally, I've wondered if I could avoid these chemicals as well. PFAS, like a lot of other chemicals, can bioaccumulate, which means it sort of moves up the food chain and becomes more concentrated in predators and apex predators. And one of the places where a lot of the cutting edge research is being done is, surprisingly, the Faroe Islands.

This small archipelago in the North Atlantic has a population of just over 50,000 people. There is no manufacturing of chemicals here. There's this quirk of local culture that people have eaten whale meat for generations.

And whale meat can have very highly concentrated levels of chemicals in it. Pilot whales is a kind of a gift from nature because over centuries we have harvested in hundreds and around thousand per year. They were seen as really a gift from, almost from heaven.

I went out to the public saying that pregnant women, especially, or women who intended to become pregnant, they should really be careful eating pilot whale meat. Dr Pal Weihe and his team found mercury was getting into the local population, from whale meat and other seafood. The scientists have studied the Faroese since the 1980s.

Okay. Every so often a new cohort of hundreds of children under one year old are added to the research. Their physical and mental development is examined all the way into adult life.

Seems that she's hearing well with both ears. They're tested for things such as balance, reaction time, body composition, lung and heart function. Even the antibodies in their blood.

As the Faroese reduced their consumption of pilot whale, the scientists saw the levels of mercury in their blood lower over time. But unlike mercury, PFAS chemicals are in everything. In the Faroe Islands people have stainproof couches and waterproof jackets, just like the rest of us.

Even in people who had very low levels of the chemicals, the scientists started spotting things that really concerned them. What we saw surprised us very much. And we saw that the negative effect on the antibody formation was much higher in children exposed to PFAS than to PCP and other substances.

People in the Faroe Islands far away from pollution, and they were exposed to these compounds at something we thought was very low concentrations. And still we found that every time that a child had a doubled concentration of PFAS in the blood, the child would lose half of the antibody. Essentially, the vaccines did not work.

It means that there is a fault, a weakness, in your immune system. It's not functioning optimally. We can see that those kids who have higher exposures have a weaker skeleton.

And there's a tendency of, at young ages to develop what we call pre-diabetes. Okay, I just do the last test. So as these studies evolve and we learn more about the links between high PFAS levels and health problems, how close are we to understanding how much is too much?

The World Health Organization experts on cancer believe that if you don't have an optimally functioning immune system, you may be more vulnerable to cancer. So we can see the various diseases that are sort of triggered, if not facilitated. I would call this as a multi-organ toxicant, PFAS.

It affects multiple targets. And it may be that different PFAS each take their pick And it may be that different PFAS each take their pick of their favorite toxicity. We are trying to decipher that.

One of the most disturbing things that persists as a scientific problem with PFAS is that there's no known way to get them out of our bodies. There's only one way that's known of, and unfortunately that's through mothers giving birth. They're offloading their PFAS to their children, both at the time of birth and through breastfeeding.

And this just has huge implications for not just our generation, but the generations to come, that we're passing these PFAS on to our children. Elsa Helmsdael is both a scientist who studies PFAS, a person who has been through the cohorts, and a mother who's had to deal with PFAS on a very personal level. I thought a lot about it, and I decided to only breastfeed for six months, even though the recommendation is that you breastfeed for a year.

Wow. Did it feel strange to think about being sort of pre-polluted or sharing your pollution with your child? Yeah, yeah.

Yeah, it did. And also, because I didn't know my own levels, and you actually give a lot of the contaminants, in this case, the PFAS, to children, so their levels go really high and your levels drop as a consequence of breastfeeding. I didn't think about it that much when I was tested myself, but I do think about a lot when it comes to my kids.

We are starting to understand that early life exposures can change the configuration of our chromosomes. And so the question is, is it something that can affect future generations if we pollute or expose the currently pregnant women? if we pollute or expose the currently pregnant women?

And this has been shown in rodent studies that it can happen. The pesticide is completely gone, but the changed DNA chemistry is not. PFAS aren't just a problem for humans.

The chemicals have been detected in animals for decades, from polar bears in the Arctic to dolphins in India. In the Faroe Islands, they're also studying the impact on wildlife. Ornithologist Sjúrður Hammer is looking at their effects, both on seabirds and to ecosystems as a whole.

We're fairly confident that the PFAS that we're finding in seabirds, for the most part, comes from their diet. There's important research done quite recently on how pollutants have a negative impact on top predators in particular, where you see high concentrations, and that has a knock-on effect on their, it could be parasite load, but it could also be their likelihood to catch infections or to survive a pandemic, like avian influenza. So if we were to lose an apex predator like the Great Skua, what are the consequences ecologically?

Ecologically, top predators are so very important in stabilizing the ecosystem. They have a kind of controlling, top-down effect on the ecosystem. Are there other consequences ecologically to these birds in particular having PFAS or other chemicals?

We very often look for sub-lethal effects. They may have more subtle effects on their reproduction, for example. And also in relation to PFAS, there are indications that the mothers pass it on to their eggs.

So there's what we call maternal transfer as well. Just as with humans. Yes.

We have documented some of the negative consequences, and we send the message back to you. Please learn the lesson. It can be irresponsible just to invent some new substances and produce them and send them out, without any control.

As more has been learned about the health hazards of these chemicals, regulation of PFAS has really picked up. It's forcing a reckoning for the chemical companies. They're seeing settlements from lawsuits that are amounting to tens of billions of dollars.

While claims that PFAS chemicals cause cancer have been litigated elsewhere, there's never been a major trial in Minnesota. Skeptics say the state's drinking water contains other contaminants, but many people living in areas with high levels of PFAS still question 3M's role. Even since the 2018 settlement, Minnesota is still working out how to deal with PFAS.

The PFAS legislation that we have, this year we named it the "Amara Law. " It will ban non-essential use. It will require labeling of any product that has PFAS in it.

These manufacturers were coming forward wanting to be considered essential. So that's how we found out there were all these products that had PFAS in them, because they wanted to be on the essential list. We didn't know how extensive PFAS chemicals were in different products.

We kept learning more and more every day of the thousands of products that contained these chemicals. And at the same time, how would any of us know? It's not listed on ingredients, it's not listed on what is used to make this particular shampoo or this particular dental floss.

We need stricter regulations on the use of PFAS chemicals and more research to be done on the long-term effects of exposure. We also need more education for the public about the dangers of these chemicals, so that people can make informed choices about the products they use. Her voice in the legislature was a voice for the community.

They saw her as she was getting weaker. I saw her as getting clearer, in many ways, stronger than she'd ever been. She was a champion for us this year, bringing awareness to this issue.

Unfortunately, you know, she passed away, I think it was three days before we had the bill on the floor for the first time. All Amara was asking for in testifying at the Capitol was for companies, who are using these chemicals, do the right thing and take responsibility for their use. Her life doesn't seem over to me because she puts so much in motion, and those things are still in motion.

And so there's no over for me yet. So there are reasons to be optimistic about our exposure to PFAS. Back in around 2006, the EPA put pressure on companies to get rid of them.

And so these long-chain PFAS, like PFOA and PFOS, which we know so much about their health harms, have been phased out mostly since then. There has been a catch, however. Unfortunately, these chemical companies didn't just do away with PFAS, they replaced them.

One of the most studied and the most known is a chemical that was made by DuPont and its spinoff Chemours, for Teflon. Instead of making C8, they started making C6, something we now call GenX. They renamed it.

Now GenX is being found in drinking water supplies. And what did we see? GenX caused the exact same three tumors in rats that PFOA, the C8, did.

Exactly the same. Liver, testicular, pancreatic. Red flags went up within the scientific community saying, wait a minute, we need to be really paying attention to the rest of these PFAS chemicals, these replacements.

Even though they may be chemically different, they've got a lot of the same toxicity and share a lot of the same characteristics. Maybe we ought to be addressing them all as a group, as a class. And that's what we've seen now emerge, is the only way we can get around this one-at-a-time regulation is to address all of them within a group.

There could be thousands of additional PFAS chemicals now out there in our environment, Rob Bilott is pursuing another class action lawsuit against a number of producers of PFAS. It could potentially involve the entire population of the United States. We have more than enough evidence, it's time to move forward and act to protect the American public.

Thank you. Just think about this. If there really are 12,000 or more PFAS, how long would it take us to get all of these studies done that these manufacturers are saying that we would need?

We'd all be gone by the time that happens. If the companies are gonna say there isn't sufficient data, they should have to pay to have the studies done. How do we short circuit this?

So I brought a new case in 2018 in federal court in Ohio, and the companies immediately sought appeal, saying this was too big. Nobody had ever had a class action this large, involving millions and millions of people. And our argument was nobody else has contaminated the entire United States and has put chemicals into the blood of everyone in the country.

This case is only this big because the harm is this big. So I always knew that I would have PFAS in my blood. Like everyone, I've been exposed to them.

I was hopeful that they would be slightly lower than average, given I've known for years where these chemicals are, and I live in an area that does not have high PFAS levels in the water. I would say that, overall, you are above the mean for someone of, for a woman of your age. So you have higher than average PFAS levels.

Any particular PFAS? The best assays really only measure about a dozen or so of these chemicals. So it's always a bit of an incomplete picture.

But we do know that some of them are more commonly found than others. And so the two most common are PFAS and PFOA. So you're actually a little bit on the high side for the PFAS and just below the 50th percentile for PFOA.

These risks are relatively low, I don't think you should rush out and get yourself tested, but the next time you see your physician for your annual checkup, you may ask for a liver function test, you may ask for a thyroid function test. I did Scotchgard a lot of shoes 10 years ago. That could actually be it.

That one has a particularly long half life, so that could actually have done it. We are a chemical society, and, you know, we are exposed to these chemicals. Now, they're not highly toxic in the sense that, you know, if you're exposed, you're definitely going to get cancer or immune problems, but they increase the risk and all the other things in your life that may increase the risk just add to that, including your genetic susceptibility.

Knowing that my PFAS levels were high sort of shows that we can't avoid these chemicals, even if we try to make very educated choices as consumers. It raises an issue that I've talked about with people in the human rights space who say our right to be born without pollution should be a human rights issue. Thankfully, there are a growing number of scientists and private companies looking for solutions.

Some have even had success in breaking down PFAS' forever bonds. But realistically, these solutions are a long way off and will cost a lot of money. And it's not like we can just stop making PFAS altogether.

They're in some really important products, like stents and medical devices and semiconductors. The next challenge is really gonna be deciding which uses are essential and which ones we can live without. Consumers also have to make a choice about whether they're willing to live without some of the convenience.

You know, are we willing to get our feet wet and wear leather shoes that haven't been waterproofed? Are we willing to have fabric on our couches that get stained? I think that a PFAS-free future is a very hard goal to think about.

I don't know that that's ever achievable. Unfortunately, people can't really make informed decisions about PFAS because of the corporate secrecy that surrounded them for decades. Scientists often say, if they'd seen some of these companies' internal documents decades ago, the world would be much further along in understanding PFAS.

When we ask people, did you know that you might be exposed to PFAS? People don't know. They ask, what is PFAS?

That is, we have not informed people that we are essentially exposing them to these toxic substances. We didn't ask for their permission. This could have been avoided.

This could have been avoided decades and decades ago. Millions of people could have avoided the exposures that we're dealing with now. I'm saying as a doctor, I think we are doing something in society that is affecting the ethics of our healthcare system because we are allowing chemical exposure to reach the population in general, and that is affecting our health and worse, the next generation's health.

In my community, I have seen neighbors and friends who have also been affected by these toxic chemicals. This is not just an individual problem, it's a community problem, and it's time for action to be taken.