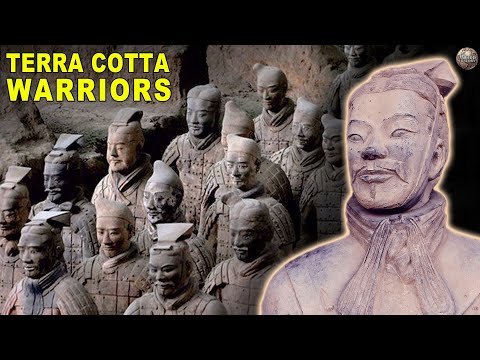

Fascinating Facts About China's Terracotta Army

673.94k views1815 WordsCopy TextShare

Weird History

Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, built the huge Terracotta Army to protect him in the afte...

Video Transcript:

[MUSIC PLAYING] Like the Egyptians, the ancient Chinese believed the items they took with them to the grave would accompany them into the afterlife. In 246 BCE, work commenced on what would eventually become the mausoleum of Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang. The emperor would require an army to protect him in the afterlife.

But instead of burying actual people with him underground, he commissioned clay reproductions of warriors, thousands of them. Today, we're going to list some fascinating facts about China's Terracotta Army. But before we get started, be sure to subscribe to the Weird History channel.

And let us know in the comments below what other amazing archaeological finds you would like to hear about. OK, we're going to China. Qin Shi Huang was born February 18, 259 BCE, and lived until September 10, 210 BC.

At the age of 38, Qin-- who was then known as Zheng, King of Qin-- conquered the other warring states and became the first emperor of a unified China as well as the founder of the Qin dynasty. Under his rule, feudalism was abolished. And drastic administrative reforms were made in an effort to avoid lapsing back into the chaos of the never-ending wars between states.

He developed an extensive network of roads, standardized weights and measures, and switched their power to a single currency. Most significantly, Chinese script was also standardized, giving the entire country, for the first time ever, a single communication system. In 215 BCE, the emperor ordered General Meng Tian begin construction of his tomb.

The project, situated underneath a 76-meter-tall tomb mound shaped like a truncated pyramid, would take 38 years to complete. Being a successful emperor means being able to defeat your enemies. And Emperor Qin was a frighteningly successful emperor.

Not only did he defeat armies in six different states of China, he massacred them. However, for the ancient Chinese, beating your enemies in the living world was only a temporary victory. And there was a decent chance a guy like Qin might have to face his enemies again in the afterlife.

It was this fear, that the militaries from the states defeated would pursue him into the afterlife, that motivated him to build his Terracotta Army. In fact, one of the reasons the Terracotta Army faces east is because that is the direction an enemy would likely come from to attack the underground mausoleum. The emperor ordered the Terracotta Army to be built almost immediately after he took the Qin state throne in 246 BCE.

According to an ancient source written by the Chinese historian Sima Qian, who lived from 145 to 90 BCE, over 700,000 laborers spent 40 years working day and night to finish the soldiers and the tomb. It's worth noting, however, that some modern historians have regarded these numbers as highly unlikely. No city in the world had a population of 700,000 at the time.

And it's estimated the structure could have easily been built in just a few years by around 15,000 men. Regardless of how many there were, these workers also molded the legs, arms, torsos, and heads for the terracotta figures, which were then assembled together. Modern electron microscopes even reveal grinding and polishing marks that are believed to be the earliest-known evidence for the industrial use of a lathe.

Needless to say, it took a while. And when the work was finally completed in 206 BC, Qin already been dead for four years. Many laborers and artisans died during the construction.

Some were possibly even executed to keep the location of the tomb and its treasures a secret. One of the most incredible aspects of the Terracotta Army is that while laborers only used about eight different molds for the soldiers, every single one of the 8,000 statues is different and unique in its own way. Each warrior supports his own facial features, which were added in clay.

And those who have seen them closely report that one can notice all of the subtle differences the craftsman included to differentiate each soldier. Aside from being separated into different ranks-- infantry, archers, generals, or cavalry-- each individual soldier features unique facial expressions, clothing, and hairstyles. They also have varying heights, with the tallest ones, of course, representing the generals.

Most of the statues are 5 feet 11 inches tall, but some actually stand as high as 6 foot 7". One of the most surprising aspects of the Terracotta Army, at least to historians of ancient China, was that the horses in the army are depicted as wearing saddles. This was a surprise when first discovered because it means that the saddle was invented by the time of that Qin dynasty, which is much earlier than was originally believed.

In ancient armies, the cavalry and war chariots were extremely important. And the terracotta steeds, accurate in size to living horses, are depicted as well-fed with erect ears, wide eyes, and open mouths. Some believe the horses resemble the Hochu horses, who live today in Gansu, while others posit they're based off [INAUDIBLE] horses from Xinjiang.

Whatever the case, the animals are good at climbing hills and racing, and are very strong. In addition to the 8,000 soldiers, archaeologists also uncovered 130 chariots pulled by 520 horses, along with 150 cavalry horses, most of which were buried in pits near the emperor's mausoleum. But surprisingly, these pits also contained non-military statues.

Apparently, the emperor feared boredom in the afterlife as much as he feared the armies of his enemies because he elected to be buried with statues of entertainers, such as acrobats, strongmen, and musicians. Bronze ducks, waterfowl, and cranes also appeared among the human statues, a sign most archaeologists have understood to mean that the emperor hoped to be surrounded by similar animals in the afterlife. As far as anyone can tell, the Terracotta Army remained untouched underground for over 2,200 years.

In fact, despite occasional reports of pieces of terracotta figures and roofing tiles being discovered in the area, nobody really knew about them until 1974. But in March of that year, a group of farmers, five brothers and their neighbor, discovered them by accident while digging a well in Xi'an, about a mile east of the emperor's tomb mound at Mount Li. Naturally, the Chinese government investigated the area.

And it quickly turned into one of the country's greatest archaeological finds. While excavating the pits, archaeologists uncovered about 40,000 bronze weapons, including battle axes, crossbows, arrowheads, and spears. Amazingly, however, even though they had remained underground for over 2,000 years, the weapons emerged in excellent condition and free of rust.

This is likely because they were covered in a protective chrome plating. While this technique was once believed to have been pioneered by the Germans in 1937, the discovery of the Terracotta Army and their weapons proved how ancient Chinese metallurgy was far, far ahead of its time. In modern times, tourists can get a look at the Terracotta Army.

But unfortunately, they can't see it in its original form. Why not? Well, after being molded, the statues also received vibrantly colored paint jobs with pigments made from various materials.

Intensely fired bones provided white pigments, while iron oxide was used for dark red. Azurite provided the blues, malachite the greens, and charcoal was used for black. However, once buried underground for several centuries, most of the statues lost their color.

When archaeologists excavated the area, the dry air took its toll and disintegrated the paint right off the statues. The lacquer beneath the paint curls in the exposed air, causing layers to flake off within minutes. Fortunately, since those original excavations, scientists have developed a solution with polyethylene glycol, known as PEG.

This chemical, which guards against that kind of air damage, is now sprayed onto any statue the moment it becomes unearthed. Today, we know that mercury is one of the world's most toxic chemicals. But the ancient Chinese, they considered it to be the elixir of life.

In fact, Emperor Qin, in his quest to live forever, ingested mercury pills regularly. Not only did this not help him live forever, it very likely contributed to his death at the age of 50. The emperor's belief in mercury may also mean his unexplored tomb is surrounded by rivers of the metal.

Chinese historian Sima Qian even claimed that 100 flowing rivers were created in the tomb and filled with mercury. While his account makes no mention of the terracotta soldiers, there's good reason to believe him on this one. Analysis of the soil in the vicinity of the tomb has shown extremely high levels of mercury.

Even though the Terracotta Army was discovered over 40 years ago, only about 1% of the emperor's tomb has been excavated. At first, archaeologists worried an excavation would damage the emperor's corpse and artifacts in the tomb. But the biggest concern today is safety.

The rumored rivers of mercury have left archaeologists struggling to find the safest way to excavate the tomb, if they can at all. The terracotta forces of Emperor Qin-- the warriors, horses, chariots, and even the emperor's tomb itself-- are spread out over a compound that is over 20 square miles in size. One pit, roughly the size of an airplane hangar, contains the soldiers.

A second contains the cavalry and infantry units. And a third holds high-ranking officers and chariots to represent the command center. And if all that doesn't impress you, keep in mind that there was originally supposed to be even more.

The tomb is believed to be incomplete, largely due to the discovery of a fourth-- empty-- pit that wasn't finished, even after the emperor died. Between 2009 and 2019, Chinese archaeologist Shen Maosheng headed a new excavation of the emperor's mausoleum. And in January of 2020, the Chinese information site Xinhuanet announced that Shen's team had uncovered 200 more clay soldiers.

According to Shen, most of the newly discovered sculptures are either holding pole weapons, bending their right arms with half-clenched fists, or carrying bows with their right arms hanging naturally, indicating each soldier's own task within the army. The new excavation is about 750 feet long, 200 feet wide, and 16 feet deep. And in total, there are more than 6,000 clay soldiers and horses.

The carved armor on each of the newly discovered soldiers seems to indicate their rank. According to the archaeologists, the new excavation greatly expanded their study on the military service system and military equipment of the Qin dynasty. It also provided new ideas for the research on the artistic style, characteristics, and manufacturing techniques of figurines in the period.

So what do you think? What one item would you take to the afterlife? Let us know in the comments below.

And while you're at it, check out some of these other videos from our Weird History.

Related Videos

14:08

These Ancient Relics Are so Advanced They ...

Thoughty2

15,855,391 views

13:48

Visiting the forgotten history of China (M...

JetLag Warriors

89,840 views

11:08

What Aztecs Were Eating Before European Co...

Weird History

1,863,507 views

39:58

The Creation of China Explained

History Scope

305,867 views

11:06

What Was City Life Like in the Middle Ages?

MedievalMadness

410,424 views

3:55

The Dark History of the Terracotta Army - ...

Guinness World Records

119,029 views

1:07:52

Who Built The Great Wall Of China And Why?

Absolute History

125,440 views

23:56

All of China's Dynasties in ONE Video - Ch...

Learn Chinese Now

1,056,231 views

44:02

Secrets Of The Great Wall | Ancient China ...

National Geographic Asia

9,496,791 views

11:09

The Most Shocking Deathbed Confessions In ...

Weird History

73,464 views

1:17:35

The Entire History of Ancient Japan

Voices of the Past

5,084,850 views

4:32

The incredible history of China's terracot...

TED-Ed

4,507,594 views

25:35

What Archaeological Sites Used To Actually...

BE AMAZED

16,014,113 views

10:15

What Sex Was Like In Ancient Greece

Weird History

67,572 views

37:47

SHANGHAI. Largest and Richest City in China!

CoolVision

1,111,904 views

8:12

The Terracotta Army

Sideprojects

86,505 views

1:27

Unearth the Hidden Origin of China's Terra...

National Geographic

56,327 views

1:12:01

Howard Blackburn: Gloucester's Most Legend...

1623 Studios

315,934 views

29:55

Most Incredible Ancient Weapons

BE AMAZED

1,791,502 views

10:27

Why King James I Was Obsessed With Burning...

Weird History

46,308 views