Divergence and curl: The language of Maxwell's equations, fluid flow, and more

4.29M views2735 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

Visualizing two core operations in calculus. (Small error correction below)

Help fund future proje...

Video Transcript:

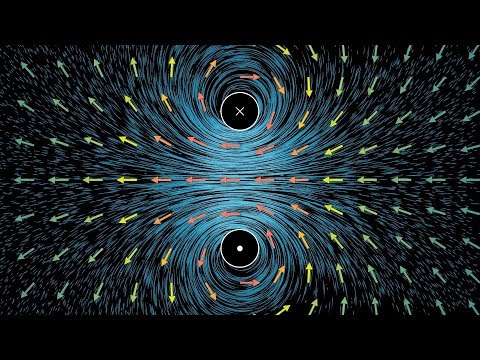

Today, you and I are going to get into divergence and curl. To make sure we're all on the same page, let's begin by talking about vector fields. Essentially a vector field is what you get if you associate each point in space with a vector, some magnitude and direction.

Maybe those vectors represent the velocities of particles of fluid at each point in space, or maybe they represent the force of gravity at many different points in space, or maybe a magnetic field strength. Quick note on drawing these, often if you were to draw the vectors to scale, the longer ones end up just cluttering up the whole thing, so it's common to basically lie a little and artificially shorten ones that are too long, maybe using color to give some vague sense of length. In principle, vector fields in physics might change over time.

In almost all real-world fluid flow, the velocities of particles in a given region of space will change over time in response to the surrounding context. Wind is not a constant, it comes in gusts. An electric field changes as the charged particles characterizing it move around.

But here we'll just be looking at static vector fields, which maybe you think of as describing a steady-state system. Also, while such vectors could in principle be three-dimensional, or even higher, we're just going to be looking at two dimensions. An important idea which regularly goes unsaid is that you can often understand a vector field which represents one physical phenomenon better by imagining what if it represented a different physical phenomenon.

What if these vectors describing gravitational force instead defined a fluid flow? What would that flow look like? And what can the properties of that flow tell us about the original gravitational force?

And what if the vectors defining a fluid flow were thought of as describing the downhill direction of a certain hill? Does such a hill even exist? And if so, what does it tell us about the original flow?

These sorts of questions can be surprisingly helpful. For example, the ideas of divergence and curl are particularly viscerally understood when the vector field is thought of as representing fluid flow, even if the field you're looking at is really meant to describe something else, like an electric field. Here, take a look at this vector field, and think of each vector as describing the velocity of a fluid at that point.

Notice that when you do this, that fluid behaves in a very strange, non-physical way. Around some points, like these ones, the fluid seems to just spring into existence from nothingness, as if there's some kind of source there. Some other points act more like sinks, where the fluid seems to disappear into nothingness.

The divergence of a vector field at a particular point of the plane tells you how much this imagined fluid tends to flow out of or into small regions near it. For example, the divergence of our vector field evaluated at all of those points that act like sources will give a positive number. And it doesn't just have to be that all of the fluid is flowing away from that point.

The divergence would also be positive if it was just that the fluid coming into it from one direction was slower than the flow coming out of it in another direction, since that would still insinuate a certain spontaneous generation. Now on the flip side, if in a small region around a point there seems to be more fluid flowing into it than out of it, the divergence at that point would be a negative number. Remember, this vector field is really a function that takes in 2-dimensional inputs and spits out 2-dimensional outputs.

The divergence of that vector field gives you a new function, one that takes in a single 2d point as its input, but its output depends on the behavior of the field in a small neighborhood around that point. In this way it's analogous to a derivative, and that output is just a single number, measuring how much that point acts as a source or a sink. I'm purposely delaying discussion of computations here, the understanding for what it represents is more important.

Notice, this means that for an actual physical fluid, like water rather than some imagined one used to illustrate an arbitrary vector field, then if that fluid is incompressible, the velocity vector field must have a divergence of zero everywhere. That's an important constraint on what kinds of vector fields could solve real-world fluid flow problems. For the curl at a given point, you also think about the fluid flow around it, but this time you ask how much that fluid tends to rotate around the point.

As in, if you were to drop a twig in the fluid at that point, somehow fixing its center in place, would it tend to spin around? Regions where that rotation is clockwise are said to have positive curl, and regions where it's counterclockwise have negative curl. It doesn't have to be that all the vectors around the input are pointing counterclockwise, or all of them are pointing clockwise.

A point inside a region like this one, for example, would also have non-zero curl, since the flow is slow at the bottom, but quick up top, resulting in a net clockwise influence. And really, true proper curl is a three-dimensional idea, one where you associate each point in 2d space with a new vector characterizing the rotation around that point, according to a certain right-hand rule, and I have plenty of content from my time at Khan Academy describing this in more detail if you want, but for our main purpose, I'll just be referring to the two-dimensional variant of curl, which associates each point in 2d space with a single number rather than a new vector. As I said, even though these intuitions are given in the context of fluid flow, both of these ideas are significant for other sorts of vector fields.

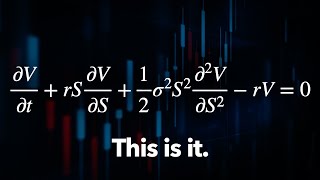

One very important example is how electricity and magnetism are described by four special equations. These are known as Maxwell's equations, and they're written in the language of divergence and curl. This top one, for example, is Gauss's law, stating that the divergence of an electric field at a given point is proportional to the charge density at that point.

Unpacking the intuition for this, you might imagine positively charged regions as acting like sources of some imagined fluid, and negatively charged regions as being the sinks of that fluid, and throughout parts of space where there is no charge, the fluid would be flowing incompressibly, just like water. Of course, there's not some literal electric fluid, but it's a very useful and pretty way to read an equation like this. Similarly, another important equation is that the divergence of the magnetic field is zero everywhere, and you can understand that by saying that if the field represents a fluid flow, that fluid would be incompressible, with no sources and no sinks, it acts just like water.

This also has the interpretation that magnetic monopoles, something that acts just like a north or south end of a magnet in isolation, don't exist, there's nothing analogous to positive and negative charges in an electric field. Likewise, the last two equations tell us that the way one of these fields changes depends on the curl of the other field. And really, this is a purely three-dimensional idea, and a little outside of our main focus here, but the point is that divergence and curl arise in contexts that are unrelated to flow, and side note, the back and forth from these last two equations is what gives rise to light waves.

And quite often, these ideas are useful in contexts which don't even seem spatial in nature at first. To take a classic example that students of differential equations often study, let's say that you wanted to track the population sizes of two different species, where maybe one of them is a predator of another. The state of this system at a given time, meaning the two population sizes, could be thought of as a point in two-dimensional space, what you would call the phase space of this system.

For a given pair of population sizes, these populations may be inclined to change based on things like how reproductive are the two species, or just how much does one of them enjoy eating the other one. These rates of change would typically be written analytically as a set of differential equations. It's okay if you don't understand these particular equations, I'm just throwing them up for those of you who are curious, and because replacing variables with pictures makes me laugh a little bit.

But the relevance here is that a nice way to visualize what such a set of equations is really saying is to associate each point on the plane, each pair of population sizes, with a vector, indicating the rates of change for both variables. For example, when there are lots of foxes, but relatively few rabbits, the number of foxes might tend to go down because of the constrained food supply, and the number of rabbits might also tend to go down because they're getting eaten by all of the foxes, potentially at a rate that's faster than they can reproduce. So a given vector here is telling you how, and how quickly, a given pair of population sizes tends to change.

Notice, this is a case where the vector field is not about physical space, but instead it's a representation of a certain dynamic system that has two variables, and how that system evolves over time. This can maybe also give a sense for why mathematicians care about studying the geometry of higher dimensions. What if our system was tracking more than just two or three numbers?

The flow associated with this field is called the phase flow for our differential equation, and it's a way to conceptualize, at a glance, how many possible starting states would evolve over time. Operations like divergence and curl can help to inform you about the system. Do the population sizes converge towards a particular pair of numbers, or are there some values they diverge away from?

Are there cyclic patterns, and are those cycles stable or unstable? To be perfectly honest with you, for something like this you'd often want to bring in related tools beyond just divergence and curl, those would give you the full story, but the frame of mind that practice with these two ideas brings you carries over well to studying setups like this with similar pieces of mathematical machinery. If you really want to get a handle on these ideas, you'd want to learn how to compute them and practice those computations, and I'll leave links to where you can learn about this and practice if you want.

Again, I did some videos and articles and worked examples for Khan Academy on this topic during my time there, so too much detail here will start to feel redundant for me. But there is one thing worth bringing up, regarding the notation associated with these computations. Commonly, the divergence is written as a dot product between this upside-down triangle thing and your vector field function, and the curl is written as a similar cross product.

Sometimes students are told that this is just a notational trick, each computation involves a certain sum of certain derivatives, and treating this upside-down triangle as if it was a vector of derivative operators can be a helpful way to keep everything straight. But it is actually more than just a mnemonic device, there is a real connection between divergence and the dot product, and between curl and the cross product. Even though we won't be doing practice computations here, I would like to give you at least some vague sense for how these four ideas are connected.

Imagine taking some small step from one point of your vector field to another. The vector at this new point will likely be a little different from the one at the first point, there will be some change to the function after that step, which you might see by subtracting off your original vector from that new one. And this kind of difference to your function over small steps is what differential calculus is all about.

The dot product gives you a measure of how aligned two vectors are, right? The dot product of your step vector with that difference vector it causes tends to be positive in regions where the divergence is positive, and vice versa. In fact, in some sense, the divergence is a sort of average value for this dot product of a step with a change to the output it causes over all possible step directions, assuming that things are rescaled appropriately.

I mean, think about it, if a step in some direction causes a change to that vector in that same direction, this corresponds to a tendency for outward flow, for positive divergence. And on the flip side, if those dot products tend to be negative, meaning the difference vector is pointing in the opposite direction from the step vector, that corresponds with a tendency for inward flow, negative divergence. Similarly, remember that the cross product is a sort of measure for how perpendicular two vectors are, so the cross product of your step vector with the difference vector it causes tends to be positive in regions where the curl is positive, and vice versa.

You might think of the curl as a sort of average of this step vector difference vector cross product. If a step in some direction corresponds to a change perpendicular to that step, that corresponds to a tendency for flow rotation. So, typically this is the part where there might be some kind of sponsor message.

But one thing I want to do with the channel moving ahead is to stop doing sponsored content, and instead make things just about the direct relationship with the audience. I mean that not only in the sense of the funding model, with direct support through Patreon, but also in the sense that I think these videos can better accomplish their goal if each one of them feels like it's just about you and me sharing in a love of math, with no other motive, especially in the cases where the viewers are students. There are some other reasons, and I wrote up some of my full thoughts on this over on Patreon, which you certainly don't have to be a supporter to read, that's just where it lives.

I think advertising on the internet occupies a super wide spectrum, from truly degenerate clickbait up to genuinely well-aligned win-win-win partnerships. I've always taken care only to do promotions for companies that I would genuinely recommend. To take one example, you may have noticed that I did a number of promos for Brilliant, and it's really hard to imagine better alignment than that.

I try to inspire people to be interested in math, but I'm also a firm believer that videos aren't enough, that you need to actively solve problems, and here's a platform that provides practice. And likewise for any others I've promoted too, I always make sure to feel good alignment. But even still, even if you seek out the best possible partnerships, whenever advertising is in the equation, the incentives will always be to try reaching as many people as possible.

But when the model is more exclusively about a direct relationship with the audience, the incentives are pointed towards maximizing how valuable people find the experiences they're given. I think those two goals are correlated, but not always perfectly. I like to think that I'll always try to maximize the value of the experience no matter what, but for that matter I also like to think that I can consistently wake up early and resist eating too much sugar.

What matters more than wanting something is to actually align incentives. Anyway, if you want to hear more of my thoughts, I'll link to the Patreon post. And thank you again to existing supporters for making this possible, and I'll see you all next video.

Related Videos

20:57

But what is the Fourier Transform? A visu...

3Blue1Brown

10,437,629 views

![Div, Grad, and Curl: Vector Calculus Building Blocks for PDEs [Divergence, Gradient, and Curl]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/lKXW7DRyyro/mqdefault.jpg)

13:02

Div, Grad, and Curl: Vector Calculus Build...

Steve Brunton

331,624 views

21:33

How wiggling charges give rise to light | ...

3Blue1Brown

810,722 views

![The most beautiful equation in math, explained visually [Euler’s Formula]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/f8CXG7dS-D0/mqdefault.jpg)

26:57

The most beautiful equation in math, expla...

Welch Labs

810,075 views

33:39

Maxwell's Equations Explained: Supplement ...

Kathy Loves Physics & History

242,727 views

25:33

Divergence and Curl

Physics Videos by Eugene Khutoryansky

437,708 views

21:44

Feynman's Lost Lecture (ft. 3Blue1Brown)

minutephysics

3,480,585 views

27:07

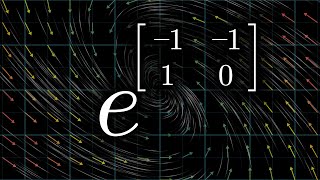

How (and why) to raise e to the power of a...

3Blue1Brown

2,860,893 views

38:41

The 4 Maxwell Equations. Get the Deepest I...

Physics by Alexander FufaeV

703,807 views

21:58

Group theory, abstraction, and the 196,883...

3Blue1Brown

3,074,287 views

40:06

A tale of two problem solvers (Average cub...

3Blue1Brown

2,759,440 views

26:06

From Newton’s method to Newton’s fractal (...

3Blue1Brown

2,838,980 views

18:36

This is why you're learning differential e...

Zach Star

3,495,118 views

14:20

ALL OF PHYSICS explained in 14 Minutes

Wacky Science

3,029,436 views

31:22

The Trillion Dollar Equation

Veritasium

8,639,870 views

8:44

Maxwell's Equations Visualized (Divergence...

The Science Asylum

377,800 views

31:51

Visualizing quaternions (4d numbers) with ...

3Blue1Brown

4,704,817 views

29:06

All of Multivariable Calculus in One Formula

Foolish Chemist

137,928 views

14:44

The Electromagnetic field, how Electric an...

ScienceClic English

1,220,243 views

27:16

Differential equations, a tourist's guide ...

3Blue1Brown

4,131,376 views