But what is a Fourier series? From heat flow to drawing with circles | DE4

17.84M views4426 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

Fourier series, from the heat equation epicycles.

Help fund future projects: https://www.patreon.com...

Video Transcript:

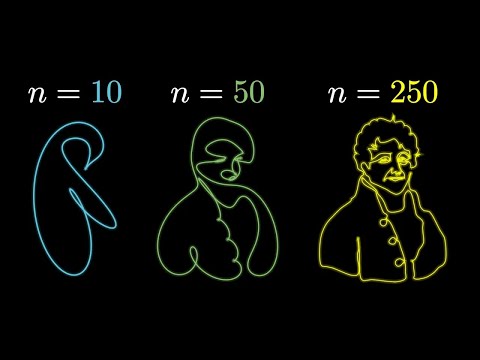

Here, we look at the math behind an animation like this one, what's known as a complex Fourier series. Each little vector is rotating at some constant integer frequency, and when you add them together, tip to tail, the final tip draws out some shape over time. By tweaking the initial size and angle of each vector, we can make it draw pretty much anything we want, and here you'll see how.

Before diving into it all, I want you to take a moment to just linger on how striking this is. This particular animation has 300 rotating arrows in total. Go full screen for this if you can, the intricacy is worth it.

Think about this, the action of each individual arrow is perhaps the simplest thing you could imagine, rotation at a steady rate. And yet the collection of all added together is anything but simple, and the mind-boggling complexity is put into an even sharper focus the farther we zoom in, revealing the contributions of the littlest, quickest, and downright frenetic arrows. When you consider the chaotic frenzy you're looking at, and the clockwork rigidity underlying all the motions, it's bizarre how the swarm acts with a kind of coordination to trace out some very specific shape.

And unlike much of the emergent complexity you find elsewhere in nature, this is something that we have the math to describe and to control completely. Just by tuning the starting conditions, nothing more, we can make this swarm conspire in all of the right ways to draw anything you want, provided you have enough little arrows. What's even crazier is that the ultimate formula for all of this is incredibly short.

Now often, Fourier series are described in terms of something that looks a little different, functions of real numbers being broken down as a sum of sine waves. That turns out to be a special case of this more general rotating vector phenomenon that we'll build up to, but it's where Fourier himself started, and there's good reason for us to start the story there as well. Technically, this is the third video in a sequence about the heat equation, what Fourier was working on when he developed his big idea.

I would like to teach you about Fourier series in a way that doesn't depend on you coming from those chapters, but if you have at least a high-level idea for the problem from physics which originally motivated this piece of math, it gives some indication for just how unexpectedly far-reaching Fourier series are. All you need to know is that we had a certain equation which tells us how the temperature distribution on a rod would evolve over time, and incidentally it also describes many other phenomena unrelated to heat. While it's hard to directly use this equation to figure out what will happen to an arbitrary heat distribution, there's a simple solution if the initial function just happens to look like a cosine wave, with the frequency tuned so that it's flat at each end point.

Specifically, as you graph what happens over time, these waves simply get scaled down exponentially, with higher frequency waves having a faster exponential decay. The heat equation happens to be what's known in the business as a linear equation, meaning if you know two solutions and add them up, that sum is a new solution. You can even scale them each by some constant, which gives you some dials to turn to construct a custom function solving the equation.

This is a fairly straightforward property that you can verify for yourself, but it's incredibly important. It means we can take our infinite family of solutions, these exponentially decaying cosine waves, scale a few of them by some custom constants of our choosing, and combine them to get a solution for a new, tailor-made initial condition, which is some combination of cosine waves. One important thing I'd like you to notice is that when you combine these waves, because the higher frequency ones decay faster, the sum you construct will tend to smooth out over time, as all the high frequency terms quickly go to zero, leaving only the low frequency terms dominating.

So in a funny way, all of the complexity in the evolution of this heat distribution which the heat equation implies is captured by this difference in the decay rates for the different pure frequency components. It's at this point that Fourier gains immortality. I think most normal people at this stage would say, well, I can solve the heat equation when the initial distribution just happens to look like a wave, or a sum of waves, but what a shame it is that most real world distributions don't at all look like that.

I mean, for example, let's say you brought together two rods which were each at some uniform temperature, and you wanted to know what happens immediately after they come into contact. To make the number simple, let's say the temperature of the left rod is 1 degree, and the right rod is negative 1 degree, and that the total length, L, of the combined two rods is 1. What this means is our initial temperature distribution is a step function, which is so obviously different from a sine wave, or the sum of sine waves, don't you think?

I mean, it's almost entirely flat, not wavy, and for god's sake it's even discontinuous! And yet Fourier thought to ask a question which seems absurd. How do you express this as a sum of sine waves?

Even more boldly, how do you express any initial distribution as a sum of sine waves? And it's more constrained than just that! You have to restrict yourself to adding waves which satisfy a certain boundary condition, and as we saw last video, that means working with these cosine functions whose frequencies are all some whole number multiple of a given base frequency.

And by the way, if you were working with some different boundary condition, say that the endpoints have to stay fixed, you'd have a different set of waves at your disposal to piece together, in this case replacing that cosine expression with a sine. It's strange how often progress in math looks more like asking a new question rather than simply answering old ones. Fourier really does have a kind of immortality now, with his name essentially synonymous with the idea of breaking down functions and patterns as combinations of simple oscillations.

It's really hard to overstate just how important and far-reaching that idea turned out to be, well beyond anything Fourier himself could have imagined. And yet, the origin of all this is a piece of physics which, at first glance, has nothing to do with frequencies and oscillations. If nothing else, this should give you a hint about the general applicability of Fourier series.

Now hang on, I hear some of you saying, none of these sums of sine waves that you're showing are actually the step function, they're all just approximations. And it's true, any finite sum of sine waves will never be perfectly flat, except for a constant function, nor will it be discontinuous. But Fourier thought more broadly, considering infinite sums.

In the case of our step function, it turns out to be equal to this infinite sum, where the coefficients are 1, negative one third, plus one fifth, minus one seventh, and so on for all the odd frequencies, and all of it is rescaled by 4 divided by pi. I'll explain where those numbers come from in a moment. Before that, it's worth being clear about what we mean by a phrase like infinite sum, which runs the risk of being a little vague.

Consider the simpler context of numbers, where you could say, for example, that this infinite sum of fractions equals pi divided by 4. As you keep adding the terms one by one, at all times what you have is rational, it never actually equals the irrational pi divided by 4. But this sequence of partial sums approaches pi over 4, which is to say, the numbers you see, while never equaling pi over 4, get arbitrarily close to that value, and they stay arbitrarily close to that value.

That's all a mouthful to say, so instead we abbreviate and just say the infinite sum equals pi over 4. With functions, you're doing the same thing, but with many different values in parallel. Consider a specific input, and the value of all of these scaled cosine functions for that input.

If that input is less than 0. 5, as you add more and more terms, the sum will approach 1. If that input is greater than 0.

5, as you add more and more terms, it would approach negative 1. At the input 0. 5 itself, all of the cosines are 0, so the limit of the partial sums is also 0.

That means that, somewhat awkwardly, for this infinite sum to be strictly true, we have to prescribe the value of this set function at the point of discontinuity to be 0, sort of halfway along the jump. Analogous to an infinite sum of rational numbers being irrational, the infinite sum of wavy continuous functions can equal a discontinuous flat function. Getting limits into the game allows for qualitative changes, which finite sums alone never could.

There are multiple technical nuances that I'm sweeping under the rug here. Does the fact that we're forced into a certain value for the step function at the point of discontinuity make any difference for the heat flow problem? For that matter, what does it really mean to solve a PDE with a discontinuous initial condition?

Can we be sure that the limit of solutions to the heat equation is also a solution? And can we be sure that all functions actually have a Fourier series like this? If not, when not?

These are exactly the kind of questions which real analysis is built to answer, but it falls a bit deeper in the weeds than I'd like to go here, so I'll relegate that all to links in the video's description. The upshot is that when you take the heat equation solutions associated with these cosine waves and add them all up, all infinitely many of them, you do get an exact solution describing how the step function will evolve over time, and if you had done this in 1822, you would have become immortal for doing so. The key challenge in all of this, of course, is to find these coefficients.

So far, we've been thinking about functions with real number outputs, but for the computations, I'd like to show you something more general than what Fourier originally did, applying to functions whose output can be any complex number in the 2D plane, which is where all these rotating vectors from the opening come back into play. Why the added complexity? Well, aside from being more general, in my view, the computations become cleaner, and it's easier to understand why they actually work.

More importantly, it sets a good foundation for the ideas that will come up later on in the series, like the Laplace transform, and the importance of exponential functions. We'll still think of functions whose input is some real number on a finite interval, say from 0 up to 1 for simplicity, but whereas something like a temperature function will have outputs on the real number line, this broader view will let the outputs wander anywhere in the 2D complex plane. You might think of such a function as a drawing, with a pencil tip tracing out different points in the complex plane as the input ranges from 0 to 1.

And instead of sine waves being the fundamental building block, as you saw at the start, we'll focus on breaking these functions down as a sum of little vectors, all rotating at some constant integer frequency. Functions with real number outputs are essentially really boring drawings, a one-dimensional pencil sketch. You might not be used to thinking of them like this, since usually we visualize such a function with a graph, but right now the path being drawn is only in the output space.

If you do one of these decompositions into rotating vectors for a boring one-dimensional drawing, what will happen is that the vectors with frequency 1 and negative 1 will have the same length, and they'll be horizontal reflections of each other. When you just look at the sum of these two as they rotate, that sum stays fixed on the real number line, and it oscillates like a sine wave. If you haven't seen it before, this might be a really weird way to think about what a sine wave is, since we're used to looking at its graph rather than the output alone wandering on the real number line, but in the broader context of functions with complex number outputs, this oscillation on the horizontal line is what a sine wave looks like.

Similarly, the pair of rotating vectors with frequencies 2 and negative 2 will add another sine wave component, and so on, with the sine waves we were looking for earlier now corresponding to pairs of vectors rotating in opposite directions. So the context that Fourier originally studied, breaking down real-valued functions into sine waves, is a special case of the more general idea of 2D drawings and rotating vectors. And at this point, maybe you don't trust me that widening our view to complex functions makes things easier to understand, but bear with me, it's really worth the added effort to see the fuller picture, and I think you'll be pleased with how clean the actual computation is in this broader context.

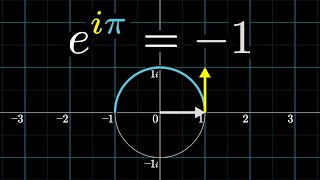

You may also wonder why, if we're going to bump things up into two dimensions, we don't just talk about 2D vectors, what does the square root of negative one have to do with anything? Well, the heart and soul of Fourier series is the complex exponential, e to the i times t. As the input t ticks forward with time, this value walks around the unit circle at a rate of one unit per second.

In the next video you'll see a quick intuition for why exponentiating imaginary numbers walks around circles like this from the perspective of differential equations. And beyond that, as the series progresses, I hope to give you some sense for why complex exponentials like this are actually very important. In theory, you could describe all of the Fourier series stuff purely in terms of vectors, and never breathe a word of i, the square root of negative one.

The formulas would become more convoluted, but beyond that, leaving out the function e to the x would somehow no longer authentically reflect why this idea turns out to be so useful for solving differential equations. For right now, if you want, you can think of e to the i t as a notational shorthand for describing rotating vectors, but just keep in the back of your mind that it is more significant than mere shorthand. You'll notice I'm being a little loose with language using the words vector and complex numbers somewhat interchangeably, in large part because thinking of complex numbers as little arrows makes the idea of adding a lot of them together easier to visualize.

Alright, armed with the function e to the i times t, let's write down a formula for each of these rotating vectors we're working with. For right now, think of each of them as starting pointing one unit to the right at the number 1. The easiest vector to describe is the constant one, which stays at the number 1, never moving, or if you prefer, it's quote-unquote rotating just at a frequency of 0.

Then there will be the vector rotating one cycle every second, which we write as e to the 2 pi i times t. That 2 pi is there because as t goes from 0 to 1, it needs to cover a distance of 2 pi along the circle. Technically in what's being shown, it's actually one cycle every 10 seconds so things aren't too dizzying, I'm slowing everything down by a factor of 10.

We also have a vector rotating at one cycle per second in the other direction, e to the negative 2 pi i times t. Similarly, the one going two rotations per second is e to the 2 times 2 pi i times t, where that 2 times 2 pi in the exponent describes how much distance is covered in one second. And we go on like this over all integers, both positive and negative, with a general formula of e to the n times 2 pi times i t.

Notice, this makes it more consistent to write that constant vector as e to the 0 times 2 pi times i t, which feels like an awfully complicated way to write the number 1, but at least it fits the pattern. The control that we have, the set of knobs and dials we get to turn, is the initial size and direction of each of these numbers. The way we control that is by multiplying each one by some complex constant, which I'll call c sub n.

For example, if we wanted the constant vector not to be at the number 1, but to have a length of 0. 5, c sub 0 would be 0. 5.

If we wanted the vector rotating at 1 cycle per second to start off at an angle of 45 degrees, we'd multiply it by a complex number which has the effect of rotating it by that much, which you can write as e to the pi fourths times i. And if its initial length needed to be 0. 3, then the coefficient c sub 1 would be 0.

3 times that amount. Likewise, everyone in our infinite family of rotating vectors has some complex constant being multiplied into it, which determines its initial angle and its total magnitude. Our goal is to express any arbitrary function f of t, say this one that draws an eighth note as t goes from 0 to 1, as a sum of terms like this, so we need some way of picking out these constants one by one, given the data of the function itself.

The easiest of these to find is the constant term. This term represents a sort of center of mass for the full drawing. If you were to sample a bunch of evenly spaced values for the input t as it ranges from 0 to 1, the average of all the outputs of the function for those samples would be the constant term c0.

Or more accurately, as you consider finer and finer samples, the average of the outputs for these samples approaches c0 in the limit. What I'm describing, finer and finer sums of a function for samples of t from the input range, is an integral, an integral of f of t from 0 to 1. Normally, since I'm framing this all in terms of averages, you would divide the integral by the length of the input range, but that length is 1, so in this case, taking an integral and taking an average are the same thing.

There's a very nice way to think about why this integral would pull out c0. Remember, we want to think of this function as a sum of rotating vectors, so consider this integral, this continuous average, as being applied to that whole sum. The average of a sum like this is the same as the sum over the averages of each part.

You can read this move as a sort of subtle shift in perspective. Rather than looking at the sum of all the vectors at each point in time and taking the average value they sweep out, look at the average of an individual vector as t goes from 0 to 1, and then add up all these averages. But each of these vectors just makes a whole number of rotations around 0, so its average value as t ranges from 0 to 1 will be 0.

The only exception is the constant term. Since it stays static and doesn't rotate, its average value is just whatever number it happened to start on, which is c0. So doing this average over the whole function is a sort of clever way to kill all the terms that aren't c0.

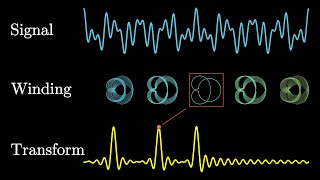

But here's the actual clever part. Let's say you wanted to compute a different term, like c2, sitting in front of the vector rotating two cycles per second. The trick is to first multiply f of t by something that makes that vector hold still, sort of the mathematical equivalent of giving a smartphone to an overactive child.

Specifically, if you multiply the whole function by e to the negative 2 times 2 pi i times t, think about what happens to each term. Since multiplying exponentials results in adding what's in the exponent, the frequency term in each of our exponents gets shifted down by 2. So now, as we do our averages of each term, that c-1 vector spins around negative 3 times with an average of 0.

The c0 vector, previously constant, now rotates twice as t ranges from 0 to 1, so its average is also 0. And likewise, all vectors other than the c2 term make some whole number of rotations, meaning they average out to be 0. So taking the average of this modified function is a clever way to kill all the terms other than c2.

And of course, there's nothing special about the number 2 here, you could replace it with any other n, and you have a general formula for cn, which is what we're looking for. Out of context, this expression might look complicated, but remember, you can read it as first modifying our function, our 2d drawing, so as to make the nth little vector hold still, and then performing an average which kills all the moving vectors and leaves you only with the still part. Isn't that crazy?

All of the complexity in these decompositions you're seeing of drawings into sums of many rotating vectors is entirely captured in this little expression. So when I'm rendering these animations, that's exactly what I'm having the computer do. It treats the path like a complex function, and for a certain range of values n, it computes this integral to find the coefficient c of n.

For those of you curious about where the data for a path itself comes from, I'm going the easy route and just having the program read in an SVG, which is a file format that defines the image in terms of mathematical curves rather than with pixel values. So the mapping f of t from a time parameter to points in space basically comes predefined. In what's shown right now, I'm using 101 rotating vectors, computing the values of n from negative 50 up to 50.

In practice, each of these integrals is computed numerically, basically meaning it chops up the unit interval into many small pieces of size delta t, and then adds up this value, f of t times e to the negative n 2 pi i t times delta t, for each one of them. There are fancier methods for more efficient numerical integration, but this gives the basic idea. And after you compute these 101 constants, each one determines an initial angle and magnitude for the little vectors, and then you just set them all rotating, adding them tip to tail as they go, and the path drawn out by the final tip is some approximation of the original path you fed in.

As the number of vectors used approaches infinity, the approximation path gets more and more accurate. To bring this all back down to earth, consider the example we were looking at earlier, of a step function, which remember was useful for modeling the heat dissipation between two rods at different temperatures after they come into contact. Like any real number valued function, the step function is like a boring drawing that's confined to one dimension.

But this one is an especially dull drawing, since for inputs between 0 and 0. 5, the output just stays static at the number 1, and then it discontinuously jumps to negative 1 for inputs between 0. 5 and 1.

So in the Fourier series approximation, the vector sum stays really close to 1 for the first half of the cycle, then quickly jumps to negative 1, and stays close to that for the second half of the cycle. And remember, each pair of vectors rotating in opposite directions corresponds to one of the cosine waves we were looking at earlier. To find the coefficients, you would need to compute this integral, and for the ambitious viewers among you itching to work out some integrals by hand, this is one where you can actually do the calculus to get an exact answer, rather than just having a computer do it numerically for you.

I'll leave it as an exercise to work this out, and to relate it back to the idea of cosine waves by pairing off the vectors that rotate in opposite directions. And for the even more ambitious, I'll leave another exercise up on the screen for how to relate this more general computation with what you might see in a textbook describing Fourier series only in terms of real valued functions with sines and cosines. By the way, if you're looking for more Fourier series content, I highly recommend the videos by Mathologer and The Coding Train, and I'd also recommend this blog post, links of course in the description.

So on the one hand, this concludes our discussion of the heat equation, which was a little window into the study of partial differential equations. But on the other hand, this Fourier-to-Fourier series is a first glimpse at a deeper idea. Exponential functions, including their generalization into complex numbers and even matrices, play a very important role for differential equations, especially when it comes to linear equations.

What you just saw, breaking down a function as a combination of these exponentials and using that to solve a differential equation, comes up again and again in different shapes and forms. Thank you.

Related Videos

4:08

e^(iπ) in 3.14 minutes, using dynamics | DE5

3Blue1Brown

2,857,931 views

20:57

But what is the Fourier Transform? A visu...

3Blue1Brown

10,382,376 views

8:25

What is a Fourier Series? (Explained by dr...

SmarterEveryDay

3,632,069 views

21:36

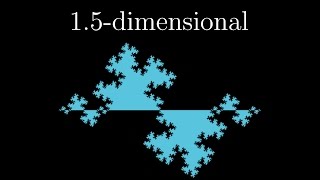

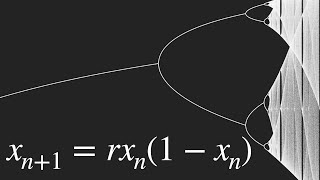

Fractals are typically not self-similar

3Blue1Brown

4,009,320 views

16:17

The Revolutionary Genius Of Joseph Fourier

Dr. Will Wood

146,472 views

14:48

The Fourier Series and Fourier Transform D...

Up and Atom

811,497 views

26:06

From Newton’s method to Newton’s fractal (...

3Blue1Brown

2,829,808 views

![The most beautiful equation in math, explained visually [Euler’s Formula]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/f8CXG7dS-D0/mqdefault.jpg)

26:57

The most beautiful equation in math, expla...

Welch Labs

686,677 views

11:14

The Man Who Solved the World’s Most Famous...

Newsthink

860,306 views

18:39

This equation will change how you see the ...

Veritasium

16,040,723 views

31:15

But what is the Central Limit Theorem?

3Blue1Brown

3,469,867 views

3:19

When a physics teacher knows his stuff !!

Lectures by Walter Lewin. They will make you ♥ Physics.

53,774,469 views

31:51

Visualizing quaternions (4d numbers) with ...

3Blue1Brown

4,685,248 views

25:35

Epicycles, complex Fourier series and Home...

Mathologer

395,715 views

27:07

How (and why) to raise e to the power of a...

3Blue1Brown

2,841,160 views

28:47

Coding Challenge 125: Fourier Series

The Coding Train

587,478 views

52:07

Lecture 1 | The Fourier Transforms and its...

Stanford

1,303,557 views

15:21

Why π^π^π^π could be an integer (for all w...

Stand-up Maths

3,408,889 views

20:52

I misunderstood Schrödinger's cat for year...

FloatHeadPhysics

373,235 views