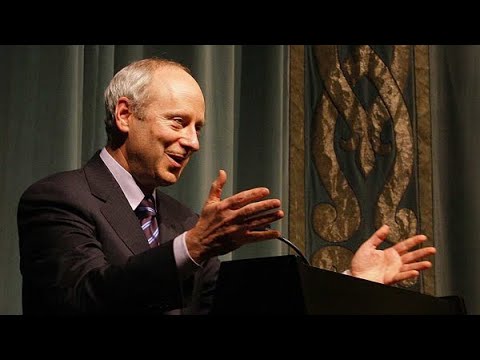

Justicia ¿Qué debemos hacer? | Michael J. Sandel

118.47k views881 WordsCopy TextShare

Fundación Juan March

Michael J. Sandel, filósofo y profesor de la Universidad de Harvard y Premio Princesa de Asturias en...

Video Transcript:

I look at three traditions of Justice that can be found in the history of ideas one tradition says that justice means maximizing pleasure or happiness or the collective well-being the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people this is the utilitarian philosophy of the English political philosopher Jeremy Bentham and later John Stuart Mill the second way of thinking about justice to be found in the tradition is the idea that justice means not maximizing happiness or well-being not simply counting numbers or maximizing GDP according to the second tradition justice means respecting individual rights and especially the

freedom to choose for ourselves how to live this second answer to the question what is justice finds its most powerful expression in the philosophy of Immanuel account the 18th century German philosopher and then there's a third tradition of Justice which says justice is not only about maximizing utility or wealth welfare it's not even only about respecting rights and freedom of choice according to this third tradition justice is about cultivating and promoting civic virtue and the common good this way of thinking about justice is in some ways the oldest in the Western philosophical tradition it goes

back to the philosophy of Aristotle I think that questions of justice and philosophy in general is too important to leave to the philosophers and so I want to try to connect the big ideas of philosophy about justice and rights and the common good to the world in which we live and I want to try to show that all of us as Democratic citizens whenever we take a position or advance an argument in the public sphere our implicitly at least relying upon one or another of these philosophical ideas now why is it why is it that

the public discourse of our societies let's say of the Western democracies why is it that our public discourse is not going very well these days I think there is a kind of emptiness in our public life an emptiness that explains why there is such widespread frustration in democratic societies with politics political parties and politicians I think the reason for the frustration has to do with the fact that our public life consists of very little attention to the big questions including large questions of the meaning and purpose of our collective lives very little attention in the

debates of the political parties or in what we see in the mass media why is this I think for two reasons one reason is that over the last few decades there has been a kind of faith in markets a faith that might even be called a kind of market triumphalism it began in the 1980s in the market ideologies of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher but it continued in the 90s even when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were succeeded by Bill Clinton and Tony Blair center-left parties in the 90s and early 2000s did not really challenge

this is my suggestion the market faith that they inherited they tried to make the case for a more generous welfare state then was advocated by the pure less a fair market faith of Reagan and Thatcher but they did not define a new public philosophy they didn't articulate a new governing vision they didn't bring into public life discussion about fundamental questions of ethics of Justice and of the good life now why didn't they partly because bringing questions of the good life bringing questions of morality into politics is risky it's risky because we in modern societies disagree

about moral questions about the best way to live and so there's a tendency to try to conduct our politics without reference to the moral convictions that lead us to disagree whether those moral convictions have to do with abortion or same-sex marriage or euthanasia or stem-cell research or the distribution of income and wealth the rising inequality between rich and poor there's a tendency in recent times to try to conceive political discourse and to enact law in a way that is neutral toward competing conceptions of the good life and so the result is a kind of empty

politics the technocratic and managerial politics that leaves ordinary men and women citizens generally deeply unsatisfied and what I think is missing in public discourse in democratic societies like ours is an explicit moral engagement with these questions about maximizing the welfare of society honoring freedom of choice and reasoning together even though we may disagree about the meaning the intrinsic meaning of social goods including citizenship including motherhood and childbearing Parenthood these are the debates we haven't had in recent decades these are the debates that have been displaced by a certain faith that markets by themselves can define

justice and can realize freedom and so the conclusion I would draw has not to do with who is right and who is wrong we haven't resolved the question we've only just begun but the kind of dialogue we've had here is an illustration of the reasoned moral discourse that seems to me missing but necessary if we are to begin to realize the ideal the democratic ideal of a politics of the common good thank you very much [Applause] you

Related Videos

14:56

Emilio Lledó | Autobiografía Intelectual

Fundación Juan March

7,204 views

1:09:51

V. Completa ¿Qué ha sido del bien común? M...

Aprendemos Juntos 2030

428,445 views

47:30

Expediciones científicas (I): Jorge Juan y...

Fundación Juan March

4,352 views

0:27

#Shorts · El papel de Margarita en Fausto

Fundación Juan March

1,747 views

1:27:59

Entrevista a Ignacio Peyró: anglofilia y t...

Fundación Juan March

2,219 views

3:49

Conferencias | Otoño 2024 · La March

Fundación Juan March

5,422 views

1:08:55

La revolución arquitectónica española · La...

Fundación Juan March

6,293 views

0:54

POWIĘKSZYĆ DZIURĘ ZA 100 000 #ekonomia #bi...

Stać Mnie

540,677 views

50:23

Stawiamy domy dla powodzian w 48 godzin! C...

Budda. TV

1,091,013 views

0:17

Ukraińcy nadal nie przeprosili za morderst...

Sławomir Mentzen

424,292 views

0:29

Czy to LEGALNE? 🤔✅ #policevsmoto #moto #s...

Bike Blaze

1,886,103 views

0:26

NIE ŻARTUJ SOBIE NA LITOŚĆ BOSKĄ! #juliavo...

Julia von Stein

254,369 views

0:43

Gdy dostaniesz 2 ze sprawdzianu.. a Ty jak...

Waksy Shorts

188,325 views

2:06

Mata - Lloret de Mar (EA SPORTS FC 25 Offi...

Mata

3,001,149 views

0:38

To NIESPRAWIEDLIWE 😥#moto #shorts #police...

Bike Blaze

310,635 views

1:00

Wiedzieliście, że w GTA IV zastawiono puła...

tvgry

385,469 views

0:49

20 TRAMPOLIN vs KULA DO KRĘGLI

reZigiusz Reakcje

333,559 views