Something Strange Happens When You Trust Quantum Mechanics

1.54M views5436 WordsCopy TextShare

Veritasium

Does light take all possible paths at the same time? 🌏 Get exclusive NordVPN deal here ➵ https://N...

Video Transcript:

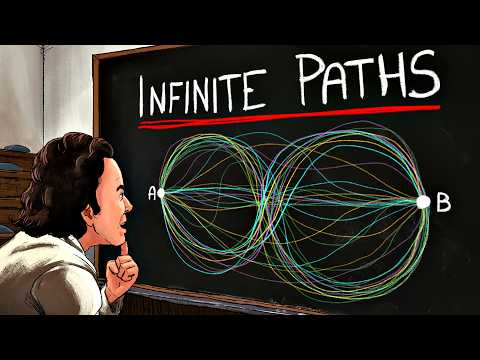

As a 42 year old who's spent most of my life studying physics, I must admit that I had a big misconception. I believed that every object has one single trajectory through space, one single path. But in this video, I will prove to you that this is not the case.

Everything is actually exploring all possible paths all at once. So let's start with a simple thought experiment. Say you're at a beach when all of a sudden you see your friends struggling out in the water.

You want to go help them as quickly as possible. So which path should you take to get there? The shortest path is a straight line, so you could head directly towards him.

But you can run faster than you can swim, and this path requires more swimming. So alternatively, you could run down the beach to minimize the distance through the water. But now the total distance is longer than it needs to be.

So the optimal path, it turns out, is somewhere in between. To be precise, it depends on the speeds at which you can run and swim. Now, you might recognize this mathematical relationship because it is the exact same law that governs light passing from one medium into another.

So light also takes the fastest path from point A to point B. What's weird about this is that as humans, we can see where we want to go and then figure out the fastest route. But light, I mean, how does light know how to travel to minimize its journey time?

Now here is where my misconception comes in. I shine a laser beam. The light just goes in one direction.

I throw a ball. The ball just goes in one direction, you know? I would have answered, there is nothing strange about this.

Light sets off from point A in some direction. And then a little while later it encounters a new medium. And due to local interactions with that medium, it changes direction, ending up at point B.

If you later find that of all the possible paths, light took the shortest time to get from A to B, I wouldn't think it was optimizing for anything. I would just think that's what happens when light obeys local rules. But now I will prove to you that light doesn't set out in only one direction.

Instead, it really does explore all possible paths. And the same is true for electrons and protons. All quantum particles.

So the fact that we see things on single, well-defined trajectories is, in a way, the most convincing illusion nature has ever devised. And the way it works all comes down to a quantity known as the action. In a previous video, we showed how an obscure scientist, Maupertuis, made an ad hoc proposal that there should be a quantity called action, which he defined as mass times velocity times distance.

And he claimed that everything always follows the path that minimizes the action. Hamilton later showed that this action is equivalent to the integral over time of kinetic energy minus potential energy. Action was useful and an alternative way of solving physics problems, especially when Newton's laws get too cumbersome.

But then, around the turn of the 20th century, action showed up at the heart of a scientific revolution: the birth of quantum mechanics. It all started with electric lighting in Germany. Think about what it's like in the 1890s, right?

Electricity being more widely available, at least in urban sectors. And things like, you know, light bulbs. They were new.

They were literally the hot new thing. Germany wanted to replace all their gas street lights with electric light bulbs. So an important question was how do you maximize the visible light given off by a hot filament?

Scientists at a German research institute, the PTR, studied how much light different materials emitted as a function of temperature. At low temperatures, each material gave off its own characteristic spectrum, mostly in the infrared, but above about 500°C all materials started to glow in the same way, with an almost identical distribution of light. The hotter the object, the more energy was emitted at every wavelength, and the peak of the distribution shifted to the left.

But they still didn't understand how it worked theoretically. So that was sort of the next step, right? If you can understand how it works theoretically, then you can use that theory to potentially design your products.

They started by imagining the simplest object possible, one that would absorb all light that falls onto it and perfectly emit radiation based on its temperature. They came up with a hole in a metal cube. This hole is a perfect blackbody because any light that shines onto it will go straight in, bounce around inside, and eventually be absorbed.

But this also makes it a perfect emitter. Any radiation inside the cube can escape through the hole unimpeded. Theorists reasoned that electrons in the walls of the cube would wiggle around, emitting electromagnetic waves.

These waves would then bounce off the other walls. When you have two waves of the same frequency, where one travels to the right and the other to the left, they can interfere in such a way that they create places where there's no wave amplitude those are nodes, and places where there is maximum wave amplitude, the anti nodes. Waves like this are called standing waves because they don't really move left or right and inside a cavity, given enough time and reflections.

It is only these standing waves that survive. All the other ones just cancel out. So a sort of order emerges from the chaos.

In two dimensions, standing waves look something like this. For shorter wavelengths or higher frequencies, you can fit more and more different vibrational modes. Inside this cube, so that in three dimensions, the total number of modes is proportional to frequency cubed, or one over lambda cubed.

The expectation was there would be more and more waves inside the cube, the shorter the wavelength. This led directly to the Rayleigh-Jeans law. At longer wavelengths.

It matched the experimental data pretty well, but at shorter wavelengths the theory diverged from experiment. In fact, it predicted that at the shortest wavelengths, an infinite amount of energy would be emitted. This, for obvious reasons, became known as the ultraviolet catastrophe.

The person to solve this problem was Max Planck, but Planck almost didn't make it into studying physics, because when he was 16 years old, he went up to his professor and asked him, well, maybe I could do a career in physics. To which his professor responded that he'd better find another field to do research in, because physics was essentially a complete science. You know, there was just a few tiny little problems that they had to clean up.

But besides that, it was over. But Planck didn't listen. By 1897, he was a professor himself, and for the next three years he struggled to find a theoretical explanation for blackbody radiation.

He tried approach after approach, but no matter what, he tried. Nothing worked. He said I was ready to sacrifice every one of my previous convictions about physical laws.

Then, in a quote ‘act of desperation’, he did something no one had thought to try. According to classical physics, the energy of an electromagnetic wave depends only on its amplitude, not its wavelength or frequency. And it could take any arbitrary value.

So any atom could emit any wavelength of light with an arbitrarily small amount of energy. But Planck tried restricting the energy so that it could only come in multiples of a smallest amount. A quantum.

And he made the energy of one quantum directly proportional to its frequency. E equals hf, where h is just a constant. Think about what this does to the radiation coming from the blackbody at a given temperature.

The atoms in the cavity have a range of energies. Some have a little bit. A few have a lot, and most of their energy somewhere in between.

For long wavelength low frequency radiation, the energy HF of one quantum is small, so all of the atoms have enough energy to emit this wavelength, and the spectrum matches the really gene's prediction very well. But at shorter wavelengths, higher frequencies, the energy of a quantum increases. And now not all of the atoms have enough energy to emit that wavelength.

This is why experiment diverges from the classical prediction. The spectrum peaks and then starts to fall because fewer and fewer atoms have enough energy to emit one quantum of that radiation. And there comes a point when none of the atoms have enough energy to emit one quantum.

So here the spectrum must drop to zero. With this approach, Planck got a new formula for the radiation spectrum. Now all that was left for him to do was to tune the parameter h.

And when he did this just right, he got his formula to match up perfectly with experiment. But he was sort of troubled by his own formula because to him it was just a mathematical trick. He had no clue why it worked.

It was purely formal. And most importantly, he had no clue what this H represented. I mean, he had introduced a new physical constant without any reason.

He wrote a theoretical interpretation had to be found at any cost, no matter how high. So from that moment on, he dedicated himself to finding one. He later reflected that after some weeks of the most strenuous work of my life, light came into the darkness and a new undreamed of perspective opened up before me.

He introduces what we now call Planck's constant, and it has the units of action. Planck's constant, h is a quantum of action. Planck later proposed that any time any change happened in nature, it would be some whole multiple of this quantum of action.

So it's kind of spooky, this breakthrough that starts the ball rolling toward quantum theory brings action in not energy and not force. Action. Gives you a hint.

At first, the quantum of action got little attention. That is, until a 26 year old patent clerk came on the scene. In 1905, Albert Einstein claimed that Planck's theory wasn't just a mathematical trick.

It was telling us that light actually comes in discrete packets, or photons, each with an energy HF. Einstein used this insight to explain the photoelectric effect how light can eject electrons from metal, but only when the frequency is high enough. If the frequency is too low, no electrons will be emitted regardless of the intensity.

The idea of quantization spread. Eight years later, Niels Bohr was trying to understand how an atom is stable if it has a positive charge in the center and negative electrons whizzing around it. Why don't they just spiral into the nucleus, radiating their energy as they go?

And what he wants to do is, he says there's something fishy about something being discrete that seems to be the new ambiguous weirdo lesson of the new quantum of action. Bohr realizes that as the electron goes around the nucleus, it has an angular momentum. Mass times velocity times radius.

So angular momentum has the same units as action. And so what he decides to do is discretize the orbital angular momentum. For no good reason he says, let me slap that on and say, and imagine the electron can only be in one unit, two units, three units of the same quantity H.

And because it's talking about motion in a circle, the factors two pi come in. So is really nh over two pi, what we now call an h bar. This comes out of nowhere.

There seems like absolutely no good reason why angular momentum should be quantized. But by doing it, Bohr finds the correct energy levels of the hydrogen atom. When an electron jumps from a higher orbit to a lower one, the energy difference is given off as a photon of a particular color of light.

Exactly reproducing the hydrogen spectrum. And that was a pretty startling thing to have fall out. I think that really was compelling.

Take some quantity with the unit of action and apply some, again, kind of ad hoc, discretization or quantization to it. Now, although it worked spectacularly well, no one can make sense of it. That is until 11 years later.

For his PhD, Louis de Broglie was contemplating the recent discoveries in physics. And his big insight was that if light could be both a wave and a particle, then maybe matter particles could also be waves. He proposed that everything.

Electrons, basketballs, people, absolutely everything has a wavelength. And he defined this wavelength analogously to light as Planck's constant, divided by the particles momentum or mass times velocity. Now, if an electron is a wave, the only way it could stay bound to a nucleus in an atom is if it exists as a standing wave.

That requires that a whole number of wavelengths fit around the circumference of the orbit. You could have one wavelength or two wavelengths or three, and so on. So the circumference two pi r must be equal to some multiple n times the wavelength.

We can sub in de Broglies expression for the wavelength to get the two pi r equals NH over mv, but we can rearrange this to get the mvr. The angular momentum is equal to NH over two pi. That is precisely Bohr's quantized angular momentum condition.

But now we have a good physical reason why it's quantized. Because electrons are waves and they must exist as standing waves to be bound in atoms because they want to have constructive interference, have a stable orbit back. That's pretty good.

You get a dissertation out of that. That's pretty good. It is this wave nature of quantum objects.

That means they no longer have a single path through space. Instead, they must explore all possible paths. Now, I have thought about and taught the double slit experiment hundreds of times without fully realizing this implication.

In the double slit experiment. I feel like the mental thing that I'm doing in my head is like, okay, well, the beam is not perfectly straight, and of course it's going to intersect both of those slits because they're really close together. You know?

But then I heard this story about a professor teaching the double slit experiment, and it makes everything so clear. So the professor starts by explaining the setup. Electrons are fired one at a time through two slits to be detected at a screen.

Now, because you can't say for certain which slit the particle went through, quantum mechanics tells us it must go through both at the same time. So to get the probability of finding a particle somewhere on the screen, you simply add up the amplitude of the wave going through one slit, with the amplitude of the wave going through the other slit and square it. But that's when a student raised his hand.

What if you add a third slit? Well, you just add up the amplitudes of the waves going through each of the three slits, and you can work out the probability. The professor wanted to continue, but then the student interjected again.

What if you add a fourth slit and a fifth? The professor, who is now clearly losing his patience, replies, I think it's clear to the whole class that you just add up the amplitudes from all the slits. It's the same for six, seven, etc.

but now the bold student pressed his advantage. What if I make it infinite slits so that the screen disappears? And then I add a second screen with infinite slits and a third and a fourth.

The student's point was clear. Even when we're not doing a double slit experiment, when it's just light or particles traveling through empty space, they must be exploring all possible paths. Because this is exactly how the math would work if you had infinite screens, each with infinite slits.

You have to add up the amplitude from each slit. That's just the way it works. According to the story, the student was Richard Feynman, and while the story is made up, the logic is flawless.

Because if you believe in the double slit experiment that you can't tell which of the two slits the particle went through, then you have to consider the possibility that it goes through both. By that same logic, any time any particle goes from place one to place two. You have to consider all the possible paths it could take to get there, including ones that go faster than the speed of light, including ones that go back in time, and including ones that go to the other side of the moon and back.

I feel like I can't go to the sun and back. You have to restrict it to be local, right? So the math doesn't do that.

I mean, you could see that just in the double slit experiment, right? And we'll do light because then there's no funky business with the speed. If you're going to say like, this path interferes with this path and these distances are different, right.

And so clearly they can’t have the same speed. So you need to consider paths that have different speeds. Feynman's way of doing quantum mechanics suggests that anything going from one place to another is connected in every possible way.

And the internet is kind of like that too connecting us to anything, anywhere, at any time. At least in theory, there are still artificial barriers like geo blocks and country restrictions that block off parts of the internet. But fortunately, there's today's sponsor, NordVPN, which can help knock down those barriers.

Just connect to one of their thousands of servers, for example, this one in the US. And it looks as if you're accessing the internet from there. The team and I travel a lot to make these videos, and using a VPN is a game changer.

It allows us to access the news sites and articles we need, no matter where in the world we are. And personally, I also love that NordVPN allows me to stay up to date with how the Canucks are doing back in Canada. Not very well at the moment.

Canucks have a real shot at the Cup this year. But to try NordVPN for yourself, sign up at nordvpn. com/veritasium.

Click that link in the description or scan this QR code. And when you do, you get a huge discount on a two year plan and an additional four bonus months for free. It's the best deal and it also comes with a 30 day money back guarantee.

So head to nordvpn. com/veritasium to try it out risk free. I want to thank NordVPN for sponsoring this part of the video.

And now let's get back to Feynman's crazy way of doing quantum mechanics. So according to Feynman, any time a particle, a photon, or even a macroscopic object moves from point 1 to point 2, it has some chance to take any path. And as preposterous as it might sound.

He found that we need to include all these paths in our calculation, where each path is weighted the same. So why then, do we not see all those crazy paths? Well, that's because we still need to add up their amplitudes.

For simplicity, imagine we only have three paths. Then here's what we're going to do. First, let's take this one.

When the particle wave starts following it, we start a stopwatch. It goes around and around very fast, and when it gets to the end point, we hit stop. We'll do the same for the other two paths.

And then we add up the arrows, square the result. And that is then proportional to the probability the particle took those paths to get there. In this case the arrow and square are pretty small, so the probability of the particle going from 1 to 2 using these paths is small.

Compare that with these three paths. For example. Well now the arrow is much larger.

And this is important. The larger the resulting arrow, the higher the probability of that event happening. Now in these examples the stopwatch is not actually measuring time.

Instead it measures something called the phase. Just as in the double slit experiment, when a wave takes a different path from point 1 to 2, it will end up there with a different phase. And this phase is what determines the amplitude of the wave at that point.

Mathematically, we can write the amplitude our stopwatch as e to the I phi, where phi is the phase. As the particle wave follows a path, its phase increases. Winding the vector around.

So now the big question is how much does the phase change for each path? Well, to answer that, imagine we split up the path into many tiny sections, each one so small that it's effectively straight. Then in each section, the particle wave goes a distance delta x and a time delta t, and the increase in phase is easy to compute.

It just depends on the wavelength and frequency of the wave. To find the total increase in phase for the whole path, we just add up all the little phase increases of all the individual sections. But we can sub in lambda equals h over mv from de Broglie, and using e we can sub in for frequency.

We can also simplify by writing h over two pi as h bar. To get this expression. Then we can take delta t to the right.

And if we make delta t infinitesimally small, then we can replace this sum with an integral. But now Dx by Dt is just velocity. So we can write this as m b squared.

Now we know that in the simplest case the total energy e is just kinetic plus potential energy. And subbing that in we're left with the integral over time of kinetic energy minus potential energy. But wait a second.

That is just the classical action. So it's action that determines how fast the stopwatch turns. As the particle moves along a trajectory, its action increases, and that is what increases the phase.

And what's important to note is that h bar is tiny. It's about ten to the -34 joule seconds, which is way smaller than the action of any everyday object. That means the phase of ordinary objects on ordinary paths spins around zillions of times, eventually pointing in some random direction.

If you consider a slightly different path, the action may be slightly different say 0. 01 joule seconds different. That doesn't seem like much, but divide it by h bar and the arrow will spin around ten to the 32 more times.

So again, it will just point in some random direction. This is what happens to almost all of the possible paths. So when you add up the phases, they just cancel out.

They destructively interfere. The only exception is for the paths closest to the path of least action, because these paths are at a minimum. So if you make tiny changes to the path to first order, the action doesn't change.

And so for other paths that are very close to the path of least action, their arrows point in basically the same direction. They constructively interfere. And that is why those are the paths we see.

This explains how light knows where to go. I mean, it doesn't. It just explores all possible paths, but the past we end up seeing are the ones that interfere constructively.

And those are the paths of least action. So really, this is how classical mechanics emerges from quantum mechanics. It's why a ball follows the trajectory it does, and how planets orbit the sun.

They don't really have a precise trajectory. Instead, everything explores all possible paths. It's just that massive particles have large actions compared to hbar, so that only paths extremely close to the true path of least action survive.

Which is why they're much more particle like. If you go to much smaller particles like electrons or photons, the actions are much smaller, and so there's more of a spread in which trajectories they actually end up taking. Now, you might say, I still don't believe you, but Casper has this incredible demo that should convince you 100% that this is really how the world works.

To do it, I've taken a light, a mirror and a camera. Now there are infinitely many paths that the light could take. And according to Feynman, we have to add the contributions of each them.

Including paths that go like this. Now, you might say he's crazy. I'm not crazy.

That's what happens. Another possibility is I could come here and go. Or it could come here and go.

Or it could come where you'd like it to come and go. And it can go over here and go and so on and so on. And these are all possibilities.

And every single one of these paths has their own little arrow. So what we can do is we can look at all those arrows and see where they line up. And so if I turn on this light, that's exactly where you see it reflects that at the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection.

But now what I'm going to do is I'm going to cover up that spot so that we no longer see the light reflect. And then I'm going to prove that really Feynman is right. That really light also goes like this.

It's just that most of the time, those effects are cancelled out. Now that sounds impossible, right? But let's zoom in to this tiny piece right here.

Then we see all these different paths and all the arrows just go around and around in circles. So when you add them up, they all just cancel out. But what if I cover up about half of them like so.

Well, now when I add up those arrows you suddenly do see a large resulting arrow. And so if I can somehow cover up this mirror in many, many tiny strips, then I should be able to get the light to reflect like this. And I can do that with this piece of foil right here on this piece of foil.

There are about a thousand lines per millimeter, and that should be enough to get this effect. So let me turn off the lights. So let's see I'm going to turn it on in 321.

We see it. That is so cool. It actually looks a lot weirder than I was expecting it to.

I was expecting more like, one spot, but there's many, many spots where it's reflecting. Oh, okay. Okay.

And just to show, I haven't been cheating you, right underneath is my finger. And even with the light on, you know, we see the light reflect. And if we remove the cover, then what do we see?

Yeah, we see exactly the normal reflection where it's always supposed to go, which is right there. And then we've got now all these extra reflections, all these extra bits where the pattern just lines up. So very, very cool.

When I was talking about this with a friend, actually, he said, yeah, but you're using a diffraction grating. That's kind of like cheating. You get all these other reflections right now and this light is just going in all directions.

And so there's one other thing. I've been super, super curious to try. I also want to do this with a laser where I shine the laser right next to it.

And then if light does take every possible path, we should also see it come off here. It probably shouldn't work. I actually have a laser right over here and we can see when I shine it.

It really does. Just go to one spot and you can see where that spot is. It's right over there, which is about the same place where we had our reflection.

And you can also see right now if we look at this view that you cannot see the laser light at all. Right. Like I could see the laser, but I have to bring it out all the way over here.

And then I'm able to sort of see the light. But if I just put it up here, you can see the reflection. Now, what I'm going to do next is I'm going to put this foil, this magic foil, and I'm going to put it over here and we can turn off this.

And now let's see what happens when I turn on the laser. Wait wait wait wait. No way, no way.

It works. It works. Wait.

What? Look where the laser is going. Oh, my God, it actually works.

What? What? This is definitely the coolest demo I've ever done.

So what I was doing is I was holding the laser, and I can show you right now. I was shining it down, like, this way off. And you could still see it reflect.

But if I take this away, it disappears. And if I put this back, it appears so that it shows really that we cannot get rid of the area which gives zero that it really is canceling out. And if we do clever things to it, we can demonstrate the reality of the reflections from this part of the mirror.

So light and by extension, everything really does explore all possible paths. It's just that most of the time the crazy paths destructively interfere. That's because the actions of nearby paths change rapidly.

Now, I've studied physics for most of my life, and I feel like I never really appreciated how important action and the principle of least action are. But now I think I finally get it. And I finally get why.

If you ask theoretical physicists what they're working on, they'll rarely talk about energy or forces. Most of the time, they'll talk about action. Nobody in particle physics approaches particle physics from a viewpoint other than least action.

But we teach physics historically, and no least action is almost like the new kid on the block for understanding physics. And so, yeah, we build up to it. But in reality, I think life's a lot easier once you realize this underlying principle, because when you do, then all you have to do is write down the correct Lagrangian so you get the right action and out come the laws of physics.

So you've got a separate Lagrangian for classical mechanics, for special relativity, for electrodynamics, and so on. It's a single mathematical framework that, once you've learned it, then you can apply it in different places in exactly the same way. The hunt for the theory of everything, right.

The thing that will encompass all of physics in reality, what people are asking is what is this Lagrangian that can spit out all of the laws of physics in this universe? That's really what they're asking. The moment we haven't really found that right.

Because we can we can sticky tape things together, but we don't know if that's the proper mathematical structure. So that's what people are hunting for. This was our second video on the principle of least action.

And I know we've covered a lot, but you might still have some questions. So we are hosting a Q&A over on our Patreon. You can submit your questions there, and we'll also post the Q&A there.

And it's all for free. If you want to submit a question or watch the Q&A. Head over to Patreon.

com/Veritasium and you can make a free account. Or you can support us a little bit as well if you'd like. I'd also like to thank NordVPN for sponsoring this video.

Check them out by clicking the link in the description or scanning this QR code. And finally, I really want to thank you for watching.

Related Videos