Adult ADHD What You Need to Know

177.91k views10991 WordsCopy TextShare

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science

This lecture is based on Dr. Barkley's recent book, Taking Charge of Adult ADHD (2021; New York, Gui...

Video Transcript:

Hello, I'm Dr. Russell Barkley, and I'm a clinical professor of Psychiatry at the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia. In this presentation, I want to speak with you about adult ADHD and what you need to know about the nature, the impairments, the causes, and the treatments for adult ADHD. To begin with, it's important to understand that while the public has only recently come to recognize ADHD in adults as a valid condition, the fact is that ADHD in adults has been recognized for more than 240 years or more. In the first reference to

ADHD in the medical literature, the German physician Melchior Adam Weikard described a condition of attention disorder that very much resembles today's adult ADHD. Subsequently, the Scottish physician Alexander Crichton also published a medical textbook. It's quite possible that Crichton even studied with Weikard during his time getting training in Germany. In any case, Crichton also described the same condition in adults but also went on to talk about another attention disorder as well. Nonetheless, what this shows is that ADHD in adults has been recognized in the medical literature for several hundred years. Not much was done about that,

however, until the 1960s and '70s when follow-up studies of large samples of ADHD children, who were then called hyperactive, were followed into adulthood, and it was discovered that at least 35% to 50% of these cases of ADHD in childhood seemed to have persisted into adulthood. These studies were compromised, however, by the fact that there were no valid, reliable, or consensus diagnostic criteria at the time in existence for diagnosing ADHD, either in children or adults; that would come later. Nonetheless, studies of these very active, inattentive children followed to adulthood showed that the disorder could persist. At

about the same time, Paul Wender and his colleagues at the University of Utah Medical Center were also publishing studies on adults with ADHD and what kinds of medications might be useful for them. But it was in the 1990s when the public was first awakened to the possibility that adults could have ADHD, even though the medical literature and research had been documenting that possibility for quite some time. This largely had to do with the publication of a trade book, "Driven to Distraction," by my friend Edward Hallowell and his colleague John Ratey, in which he talks about

adult ADHD. At the same time, specialty clinics were being set up in the United States to see adults with ADHD. At first, these clinics were started by clinicians who specialized with children, such as child psychiatrists and psychologists. This is because our adult colleagues in psychiatry and psychology did not yet recognize that ADHD could be a legitimate adult diagnosis. So, in order to treat these adults, those people already responsible for treating children with ADHD began to open clinics to see these adults. From there, the information spread out to other clinicians that this was a valid condition

in adults and that many children diagnosed with it in childhood would continue to have ADHD upon reaching adulthood. By the turn of the century in the 2000s, numerous specialty clinics began to operate in the United States and elsewhere, headed by professionals who now did specialize in adult ADHD, and this trend continues to date, so that there has been a growing percentage of adults with ADHD who are getting appropriate diagnosis and care. Now, whereas in previous decades this was certainly not the case. How do we diagnose ADHD in children and adults? Currently, we use a manual

published by the American Psychiatric Association, known as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. It is now in its fifth edition, published in 2013, and so it is called DSM-5. The DSM criteria for the diagnosis are shown on the following slides. First, there is a list of inattention symptoms that have to occur often, and the individual must have at least five or more of these symptoms. These symptoms include problems with failing to give close attention to details, difficulty sustaining attention to tasks, not listening to directions or to others, not following through on instructions, problems

with organizing one’s tasks or activities, problems with avoiding tasks that require sustained mental effort (what we call procrastination), losing things necessary for tasks, being easily distracted, and being forgetful in daily activities. These are the nine attention symptoms, and if an adult has at least five or more of these, it is considered to be developmentally inappropriate or deviant, and it is the first step toward diagnosis of the disorder. The next set of symptoms deals with hyperactive and impulsive behavior. Again, the adult must have at least five of these symptoms, and the symptoms must have occurred often

or more. This helps to separate these problems from normally occurring behavior in the typical adult and child population. So, these symptoms include things like being very fidgety or squirmy in one's seat, leaving the seat in one's classroom or at work inappropriately. For children, it includes running about or climbing on things excessively, although we don't hear that complaint in adults. Difficulty playing quietly or engaging in leisure activities quietly, in the case of adults, seems to always be on the go or driven by a motor (meaning very active behavior), talking excessively, often blurting out answers before questions

are completed, having difficulty awaiting their turn (such as when waiting in line or in traffic), and so on, and interrupting or intruding on others impulsively. So, these are the nine symptoms that we look for. Now, the problem with these symptoms is that they mainly apply to children. The hyperactivity declines markedly with age such that, by adulthood, many of these hyperactive symptoms are no longer evident if they were in childhood. It is the symptoms of impulsiveness that are quite persistent, and here you see they mainly have to do with excessive speech and interrupting others while... They're

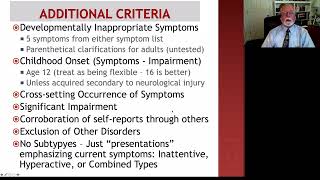

talking, but there are other symptoms as well that I will show you in just a moment. There are more criteria besides this. Not only does an adult have to have at least five symptoms on either of those lists, it doesn't have to be both, just either of them; the symptoms also have to be considered inappropriate for their age. The best way we measure that is through the use of behavior rating scales that are completed by the adults and by others who know them well. We can then compare their answers to the answers we would get

from the general population, and that helps us to decide just how far from normal the adult is in these symptoms. Now, we do require that the symptoms have developed sometime in childhood or adolescence, and although the DSM-5 says that the symptoms should be present by age 12, that's not really true. They can develop after that as well; generally, as long as the symptoms have developed sometime around 18 years of age or younger, we would consider this to be a legitimate case of ADHD. The reason for that is that adults are not very good at recalling

exactly when their symptoms might have developed. In fact, my studies show they're often off by about four years or more; that is, they often say the symptoms developed about four years later than they actually did. So we don't want to place too much emphasis on the age of onset; as long as the symptoms occurred sometime during the developmental period, then we would consider the criteria to have been met. Even then, some people can develop ADHD later in adulthood secondary to some neurological injury, such as a traumatic brain injury experienced during a fall, a car accident,

or playing sports, or possibly from some neurologic disease or tumor, such as stroke or dementia or other things. So it's quite possible for people to show the symptoms of ADHD following some event that compromises the integrity of the brain, particularly the front part of the brain. Now, these symptoms have to occur in multiple places, not just one situation. So we look for them to exist in their home life, in their work, in any school settings in which they may be participating, or even out in the community. In the case of adults, we also see whether

it affects things like their driving, their management of money, their ability to live with and engage in relationships with other people, and of course, their ability to raise their children, should they have children. So we're looking across many domains in order to see that the symptoms are affecting at least one or more of these. We want the symptoms to produce significant impairment or harm to the individual so that the individual is not functioning well in those situations that I've mentioned, like their home life or in their work life as well. So we must be seeing

that there are adverse consequences that are occurring in these domains of major life activities as an additional requirement for diagnosis. Now, because adult ADHD often interferes with self-awareness, we want to corroborate what the adults tell us about themselves through others who know them well, because in some cases, particularly with teens and young adults, they often underreport the severity of their problems. So it's very important that we obtain information from elsewhere, especially people who know them well, in order to validate or corroborate these self-reports. Now, mental health professionals also need to exclude other disorders that might

be producing problems with attention, such as depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis or schizophrenia, anxiety, and so on. We can usually rule out those other conditions as causing the problem because they don't usually show problems with attention, impulsiveness, and hyperactivity that date back to childhood and have been largely chronic in nature. Only ADHD seems to be a chronic, unremitting pattern of those symptoms that starts in childhood. Now, we also like the symptoms to have persisted for at least six months or longer. In the case of adults, that's easy to do, especially since the symptoms developed in childhood

or adolescence. Earlier versions of the DSM said that there were three types of ADHD; we no longer believe that that is the case. So in DSM-5, we changed the term from subtypes to presentations, so that there is a predominantly inattentive presentation in which mainly the symptoms of inattention are the most problematic. But some people may show up with problems more with impulsiveness and maybe hyperactivity, in which case we would call that the hyperactive-impulsive presentation. But the majority of children and adults who come to clinics have the combined presentation in which they meet criteria for having

at least five or more symptoms on both lists of symptoms. So now you understand how we go about making a diagnosis of ADHD in adults. Here are some things to consider. Although the symptoms of ADHD, as I have described them, are correct, clinical researchers like myself have a much deeper appreciation for or understanding of the nature of these symptoms. So let me explain them the way I understand them and not just the way the DSM-5 lists them. That is because the symptoms in the DSM-5 are fairly superficial, were developed mainly on children, and were not

well tested with adults. As a result, they don't seem to apply to adults as well as they do to children. So it helps if the clinician, the professional, has this richer understanding of what to look for in someone with adult ADHD. Now, we've said that ADHD involves these two dimensions of neuropsychological deficits. The first of these to develop in childhood is usually the problem with inhibition. The hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, what they look like, however, is much more than just motor hyperactivity or restlessness. It's not just a problem with inhibiting motor actions; in addition, as the DSM-5

points out, there are problems with inhibiting verbal behavior, which are manifested through things like talking excessively, not giving others a chance to converse in the conversation, interrupting others inappropriately, and so on. Besides those two problems with inhibition, there are at least three others that are not mentioned in the DSM-5. One of them is impulsive thinking or cognition, in which the individual has difficulties suppressing unwanted thoughts from entering into their stream of consciousness, particularly when they are working on tasks or pursuing goals. During those times, most typical people would suppress these unwanted thoughts and focus on

the task at hand, but people with ADHD, because of their inhibitory problems, often have difficulties not thinking about these irrelevant ideas or thoughts. In addition, we also see adults with ADHD engaging in very rapid decision-making, which means that they don't think about or deliberate on the consequences of the actions they're considering before they do them. Instead, they appear to think impulsively and act on those ideas impulsively as well. Another problem with impulsiveness is what we call impulsive motivation. This simply means that people with ADHD prefer to have more immediate but smaller rewards and other consequences

rather than deferring their gratification and working toward larger, later rewards. So that delay of gratification is very difficult for them, and they often find themselves engaging in things that give them immediate pleasure or rewards, even if these are not the most optimal ways they should be spending their time. In teens and young adults with ADHD, we may see this in their development of internet or gaming addictions, among others, in which they are opting to play games because they're such fun and provide immediate gratification rather than studying, doing schoolwork, or completing the tasks they've agreed to

do for their employers. Yet another area of impulsiveness is impulsive emotion. This is also not mentioned in the DSM-5, but it is just as central to ADHD as are the other symptoms that are mentioned in our diagnostic manual. By impulsive emotion, or poor emotional self-regulation, what we mean is that people with ADHD show their emotions very quickly when they've been provoked. Now, these emotions are different from what we see in a mood disorder in several respects. First, the emotions are provoked by things that happen to us, just as the emotions of typical people. What distinguishes

them is that the person with ADHD shows them very quickly and often to a more extreme degree. But we can also understand the emotion; it's reasonable and rational; it makes sense to us. We too might have felt the same way, but we wouldn't have shown the emotion — or at least not to that degree. We would have inhibited the initial emotion and engaged in various ways to calm ourselves down. Adults with ADHD have difficulty doing that. Their emotions are quite impulsive, often more extreme, and they struggle to gain control of them if those strong emotions

have been provoked. However, they are understandable nonetheless. In a mood disorder, the emotions are of long duration, not short as in ADHD. The emotions may last for days or weeks, and we also don't understand what provoked them. They don't make sense to us; we can't see what's making the person depressed, manic, or necessarily anxious. Furthermore, the emotions are often extreme, capricious, and labile or variable, especially the emotion of irritability. So all of these are ways that we distinguish a mood disorder from the emotional problems that adults with ADHD have. Again, the emotions are provoked but

impulsive, a little more extreme, hard to gain control of, but they're understandable, they're situation-specific, they often pass relatively quickly, and they're not bizarre or extreme — at least not like in a mood disorder. You can see that there are at least five domains in which inhibition interferes with functioning in adults: motor behavior, verbal behavior, their thinking, their motivation (they want things now rather than later), and their emotions. As I've said earlier, the hyperactive behavior often seen in children with ADHD declines markedly with age, so that by adulthood, those hyperactive symptoms are not very useful for

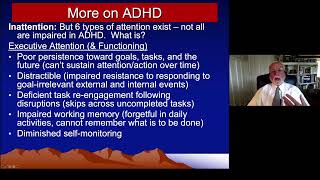

making a diagnosis. The adult may feel restless, may show some need to be busy and engage in lots of different tasks which they don't finish, but we don't see them climbing on furniture, driven by motors, or in other ways acting hyperactive. However, they may still show signs of some restlessness when they are required to stay seated for long periods of time. Now, how can we understand the inattention symptoms beyond just the way they're described in the DSM-5? We need to understand that there are at least six different kinds of attention that our brain allows us

to have. ADHD does not interfere with all of these kinds of attention, such as arousal, alertness, the focus of attention, and so on. Instead, ADHD interferes with sustained attention; a better term for that is persistence toward goals, toward tasks, and persistence toward the future in general. ADHD is interfering with the ability to string together long chains of motor actions needed to accomplish a longer-term goal. They can't persist toward their goals or assigned tasks. In other words, the problem with attention is one of attention to the future, and that's a very special kind of inattention. Along

with that, in order to persist toward our goals and our future, we have to resist responding to distracting events, which are simply events that are not relevant to the goals that we're pursuing, and we must inhibit responding to these if we are going to accomplish the work we want to do. And that is what adults with ADHD struggle to do as well; they often react to events that are distracting. happening around them, even if those events have nothing to do with what they should be doing at this time. Now, we all will get distracted from

time to time during our work, and when we do, we deal with the distraction and then we get back to finishing the task at hand. We return to or re-engage the incomplete work. People with ADHD struggle to do that also. Once they've been distracted away from their work or tasks, they find it hard to go back and resume the incomplete goal or activity; instead, they are off pursuing other things, other distractions, skipping from one uncompleted activity to another and not finishing much of anything. Now, the ability to re-engage work that we've been distracted from is

not a problem with attention; it shows that there's a problem with working memory. Working memory is a very special kind of memory that is given to us in our frontal lobes, the forward part of the brain, and in this kind of memory, we are actively holding in mind our goals, the steps we intended to pursue to get there, and what progress we're making toward those goals. It's all actively held in our mind, and we're using it to keep ourselves on task, focus our effort, and persist over time. People with ADHD have serious impairments in working

memory. They can't hold in mind information about what they're supposed to be doing for very long, and it's easily disrupted by other events that happen around them that aren't relevant to the goal but nonetheless distract them. In that way, they're a lot like older people, such as myself. Once you get past age 55 or so, you begin to lose some of your working memory, and you may go into a room and forget why you went there because you couldn't hold the goal in mind for very long. So, we see the same thing in ADHD, but

it is much worse. Finally, as I've said, another attention problem that goes with ADHD is attention to the self—the ability to be aware of and monitor ourselves as we go about our daily activities and to compare what we're doing against what our goals were. So, self-awareness or self-monitoring is very important to accomplishing our goals, and adults with ADHD, as I said earlier, often have diminished self-awareness. That is why we can't rely exclusively on what they tell us about how they're functioning in their life; we must get information from others. Excuse me, you may not know

it, but I have just suggested that ADHD involves most of the brain's executive functions. The executive functions are that set of mental abilities that we use to pursue goals, get ready for the future, and solve problems. People with ADHD, as is evident here, have lots of difficulties with these executive abilities. Excuse me, these executive functions give us self-control and self-regulation over time to prepare for the future in order to improve our welfare, and people with ADHD have lots of trouble with that. So, let me go back and specifically list for you, excuse me, the seven

executive functions that ADHD is likely to impair. The first, as I've mentioned, is self-awareness and self-monitoring. The second, I've mentioned, is inhibition or self-restraint. The third is working memory, and there are two kinds of working memory: nonverbal, in which we use visual imagery to think about what we're going to do, to reflect back on our relevant past, which we call hindsight, and then to think ahead from that about what might happen next. That's the non-verbal aspect of working memory: holding images about the past and the future in mind that are related to our goals. The

second type of working memory is verbal working memory. Basically, it is self-speech. We talk to ourselves. In the case of little children, they do it out loud, but by the time they are out of elementary school, this voice has moved into their head. They've internalized it, and they now have a mind's voice that they can use to talk privately to themselves in order to guide themselves to do what they've been asked to do or to pursue their own goals. So, think of working memory as the mind's eye (visual imagery) and the mind's voice. We use

both of these in order to stay on task and accomplish our goals, and people with ADHD struggle with both of them. I like to think of working memory very much like a GPS in a car. We get in the car, and we enter a destination into the GPS—that's our goal, right? Then the GPS brings up images of the relevant surroundings, the maps, and it also gives us verbal instructions on how to move through that region, those maps. So, the GPS is using images and words to guide us over time to reach a destination, and working

memory works very similarly to that. And so, when it's disrupted, as it is in ADHD, people will have a lot of difficulty accomplishing their goals, pursuing the future, and staying on task. Now, I've mentioned the others already: there's a problem with emotional self-regulation, and there's also a motivational deficit—problems with self-motivation. Instead of pursuing longer-term goals that have bigger rewards, which requires that we motivate ourselves, people with ADHD instead opt to do shorter-term things for which they can get more immediate rewards and consequences that don't require self-motivation. Finally, although I haven't mentioned it before, ADHD adults

and children have problems with planning and problem-solving, both of which are very important to future-directed, goal-oriented behavior. We must be able to think about various plans and options for what we hope to accomplish and choose the best one. And if we encounter problems or obstacles along the way to our goal, we have to... Be able to stop, inhibit, think about what we're doing, and see if we can come up with multiple other possibilities that might overcome the problem. Problem-solving is something people with ADHD struggle to do as well. You can now see that ADHD in

an adult is a much more impairing disorder than people originally believed. It is a problem not just with attention and inhibition, but with the executive functions and self-regulation. This helps us to understand why, if ADHD in an adult is not treated, it can lead to all of the difficulties you see on this slide: difficulties with education, problems with family conflict, and difficulties getting along with others—not just people in the family, but people we encounter outside, friends, and acquaintances. It can lead to problems following the law, in which people with ADHD are more likely to engage

in illegal behavior or antisocial behavior. It can lead them into substance abuse, such as smoking more, using more marijuana or alcohol, or even using illegal substances. Again, this is because of their impulsiveness, which leads them to be prone to addiction. We see a pattern of risk-taking behavior that may be evident in their sexual behavior, in which they engage in more sexual activity with others without using contraception. This leads to an increased risk of teenage or young adult pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases because they don't think through the consequences of what they're doing. Their risk-taking often

leads them to experience many more accidental injuries than do other people—not just injuries at home, but while driving, while engaged in sports, or while working in the workplace. People with ADHD suffer a lot more in their accidental injuries, to the point where children with ADHD are twice as likely to die by age 10, and adults with ADHD are five times more likely to die by age 45 as a result of their risk-taking and proneness to accidental injuries. Among adolescents, there's also a growing risk for attempting suicide because of their impulsiveness—if they're depressed and they think

about suicide, they are more likely to attempt it because of their lack of inhibition. They also have difficulties with risk-taking while driving: speeding with a motor vehicle, parking where they shouldn't, and getting more traffic citations for all sorts of driving infractions, including driving while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. As you can imagine, these problems with executive functioning will interfere not just with school but with work performance, their occupational functioning. Of course, people who are impulsive don't manage their finances or their money very well, particularly their use of credit cards for impulse buying. People

who don't think about their actions also don't look after their health very well. Instead of eating well with healthy nutrition, exercising often, and getting good medical and dental care that is preventive in nature, they tend to avoid doing those things, eating poor diets often filled with junk food, high in carbohydrates and sugars, and often low in proteins or healthier foods. This leads them to a growing risk for obesity—twice the risk for obesity of other adults—and eventually to risk for coronary heart disease (CHD). You can imagine that these deficits in self-control would certainly affect one's marriage

or one's cohabiting relationships with others, and we do see that impulsiveness leads to problems in living at home and accomplishing our work at home when we live with others because of impulsive emotions. There's a greater likelihood of reactive aggression, frustration, and hostility, and sometimes that can lead to interpersonal violence toward others when they're provoked. Should they have children, you can well see that these problems with self-control would interfere with their ability to monitor their children, create more consistent home routines, give more reasonable consequences for good and bad behavior, control their emotions more when they have

to deal with their children, and become frustrated in doing so. So, ADHD leads to a variety of impairments across nearly every major domain of life activities that we have studied to date. Luckily, treatment reduces many of these risks, particularly treatment with medication. Now, what causes adult ADHD? It's essentially the same things that lead to Childhood ADHD, with perhaps a couple of exceptions. ADHD in children and adults is highly inherited; it is genetically influenced. Indeed, ADHD is one of the top three most genetically influenced psychiatric disorders we know of, the other two being bipolar disorder (known

as manic depression) and autism spectrum disorder. The genetic influence on ADHD is between 70 and 80%, which means that about 75% of the differences among people in the population in their ADHD symptoms is the result of differences in their genes—the gene interactions that build and operate the brain and, as a result, determine some of these behaviors. So far and away, genetics is the leading cause of ADHD. Now, while often it is inheritance that we're talking about here, the genes for ADHD exist in other relatives. Other relatives are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, and

therefore the biological offspring of these people are more likely to get those genes and develop ADHD. Simply put, ADHD runs in families at a much higher rate than we would expect by chance alone. If an adult has ADHD, their child is eight times more likely than a typical child to have the disorder. Put another way, nearly half of the children of adults with ADHD will also have ADHD if their parent has the genetic form of the disorder. If a child has ADHD, 25 to 35% of their brothers and sisters will also qualify for the disorder,

and if a twin has ADHD, their identical twin is 75 to 90% likely to have the same disorder. All of the figures I've given you clearly show you how inherited, how genetic ADHD actually is. But more recently, we've learned that there's another genetic cause of ADHD that doesn't involve inheritance. The way I've described it here is what we call “new” or “de novo” mutations. What happens is that as adults grow up and wait to have children, they accumulate mutations in their DNA—in their eggs and sperm. So if we did a blood test, we wouldn't see

these mutations, but if we looked more closely at their gametes—their eggs and sperm—we would see that they have more mutations in them. Now, since many people are waiting to have children, particularly here in the West, often not having their first children until they're about 30 years of age or older, adults who wait that long have 8 to 10 times more mutations in their eggs and sperm than if they had had children in their 20s. So these mutations pile up, and eventually, they reach a point where enough mutations exist to cause ADHD in the offspring of

those parents, even though no one else in the family before them ever had ADHD. It has to do with the accumulation of new mutations as a result of delaying childbearing. This is more likely to affect fathers than mothers, but research shows that it occurs in both sexes of parents. So one cause of ADHD, accounting for about 10% of all ADHD cases, are these new cases—de novo cases—that arose from genetic mutations in the parents' eggs and sperm. Now, about two-thirds of ADHD can be explained by these genetic causes. What about the other third? Well, as this

diagram shows, there are other things that can create ADHD in a child and have it persist into adulthood. All of these have to do with things that damage the brain, particularly during pregnancy or early childhood. Such things as being born very prematurely and having low birth weight often lead to bleeding in the brain and small injuries. But if these injuries are sufficient, they can lead to ADHD, and about 35% to 45% or more of babies born very premature and needing to go into a neonatal intensive care unit will go on to develop ADHD in childhood.

Another reason for ADHD is mothers who drink during their pregnancy—that is, use alcohol. Alcohol is a toxin to the brain, and it can poison the development of the frontal lobe in particular. If done in large quantities, it even leads to fetal alcohol syndrome. But even just alcohol exposure is sufficient to increase the risk for ADHD about 2.5 times more than would be the case if the mother had not consumed alcohol at all during her pregnancy. Other toxins in the environment, such as lead, mercury, and so on, heavy metals in the environment, can lead to damage

to the brains of young children or to the brain of a fetus during pregnancy if the mother is exposed to these toxins. So poisons can disrupt the formation of the frontal lobes, the executive brain, and lead to ADHD. More research now is showing that frequent illnesses and infections in the mother during her pregnancy increase the odds that her child will have ADHD. It's not clear whether it is the virus or bacteria that is doing this by directly affecting the child's brain development or if it's the mother's immune system that is reacting to the infection—perhaps overreacting

to it, leading to systemic inflammation—and possibly to her immune system or even the baby's immune system beginning to attack the brain. We know that there are a number of adult medical syndromes that can arise from autoimmune disorders, where the immune system turns on the body and begins to damage it in some way. A good example you may know would be multiple sclerosis, but there are other such autoimmune disorders in which the immune system is damaging the body, and in this case, the brain. The number of pregnancy complications, and especially delivery complications, are also risk factors

for ADHD, such as not getting sufficient oxygen during delivery, a very prolonged delivery that might be leading to some traumatic damage to the child's brain as it is stalled in the birth canal, and so on. So there are many other things that could happen—just about anything that might affect brain development adversely could potentially give rise to ADHD in a child and have that persist into adulthood to create adult ADHD. Now, ADHD in children and adults is rarely seen by itself. Oftentimes, we see other disorders developing alongside the ADHD, and you'll see a list of them

here. Some of the most common are oppositional defiance disorder, a pattern of defiance in children, a pattern of stubbornness, anger, and irritability toward others. Oftentimes, this pattern of anger and hostility toward others, temper outbursts, and so on can persist into adulthood. Conduct disorder or antisocial behavior is another problem that I've already mentioned that can develop in adolescents. In about 25% of ADHD children and adults, those who go on to develop conduct disorder or even antisocial personality disorder, which is related to it, are also at high risk for substance use and abuse. About 25% of adults

with ADHD may develop mild depression, or be demoralized, or even qualify for major depressive disorder. The risk for depression seems to be highest in the adolescent years and declines somewhat after that, although being demoralized is a very common feature of adult ADHD because of their frequent failures to achieve all that they had hoped to do in their lives or been asked to do in their employment as a result of having ADHD. There's a new mood disorder called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder—that's a pattern of extreme depression and irritability coupled with explosive temper, aggressiveness, and even destructive

behavior. Only about 10% of children with ADHD, or less, ever develop that disorder. Anxiety disorders increasingly occur with ADHD as children grow older, such that in childhood, we may see 15% to 20% or more having an anxiety disorder alongside their ADHD. However, if the ADHD goes untreated until adulthood, that figure more than doubles, reaching 40% to 50% of adults with ADHD seen in our clinics who usually have an anxiety disorder accompanying their ADHD. Approximately 5% of people with ADHD might develop a tic disorder; it's a little higher in children and much less so in adults.

A few of them may go on to develop Tourette syndrome, but ADHD is not a major risk factor for those two issues. However, if a person already has a tic disorder or Tourette syndrome, they carry a very high risk of having ADHD along with it, with anywhere from 40% to 80% of such cases having ADHD as a coexisting disorder. About 20% to 25% of children with ADHD have some symptoms of autism spectrum disorder, often toward the higher end of functioning and being relatively mild. Conversely, over half of children with autism have ADHD, showing that the

two disorders coexist. Intellectual disability may occur in ADHD to a slightly greater extent in the population; about 2% to 3% of adults have intellectual disability, what we used to call mental retardation. That figure is about two to three times higher in people with ADHD, with about 4% to 7% qualifying for having this intellectual subnormality. One of the more common learning problems seen in ADHD are specific learning disabilities. Half or more of children and adults with ADHD have difficulties with reading, writing, language, spelling, and arithmetic. We call these specific learning disorders because they interfere with a

specific type of academic achievement, so the relationship between ADHD and learning disabilities is quite high. Additionally, more than half of children with ADHD are diagnosed with developmental coordination disorder, having both fine and gross motor incoordination more so than typical people of the same age. They are also more likely to have difficulties with language development and communication, particularly with expressive language, which we've discussed. The excessive talking and difficulties with motor coordination of the mouth may affect communication. Finally, ADHD does link up, to some extent, with adult personality disorders. The three most common are antisocial personality disorder,

which some people think of as sociopathy or psychopathy, a pattern of chronic violation of the rights of others and of the legal system; borderline personality disorder, which may occur in about 15% to 20% of these adults; and, in about 10% or less, we might see passive-aggressive personality disorder. All of this is simply to explain that ADHD rarely occurs alone. Over 80% of children and adults who come to clinics for an evaluation for ADHD will have at least one of these other disorders, and more than 50% will have at least two of them. When adults go

to the clinic, they can expect the clinician to follow these steps to evaluate whether they have adult ADHD. The first step will be to ask them what they're concerned about, of course, in a very open-ended interview: "Why are you here? What troubles you?" Then, we'll ask how long those problems have existed. If what we hear begins to sound like symptoms of ADHD, the clinician will then consult the DSM-5 and go through the 18 symptoms of the disorder. Although I've noted that the DSM requires at least five symptoms from each of the two symptom lists, research

shows that even four symptoms on either of those lists is very inappropriate for an adult, so I argue that clinicians should be urged to use four as the symptom threshold, not five. We want to ensure that the symptoms are truly deviant; that is, they occur to a degree that is inappropriate for the adult's age and sex. The best way to do that is to provide them with a rating scale of these ADHD symptoms, where they can assess how often they experience each symptom. We can then add up their score and compare it to a table

of norms derived from the general population, allowing us to see how far from normal—or how deviant—they are. People with ADHD often fall above the 93rd percentile in the population concerning how many symptoms they exhibit and how severe those symptoms are, indicating that these are not common. We aim to screen out typical behavior by using these rating scales. Next, we review the DSM criteria again for how they were as children, asking them to recall their symptoms from when they were 12 to 16 years of age or younger, giving them a very broad window in which to

think about their history. We look to see if they had six or more of these symptoms on either the inattention or the impulsivity symptom list. We want to ensure that the onset occurred sometime in childhood or adolescence, but as I mentioned, it's not as crucial that we apply a hard and fast specific number as part of our criteria. We're seeking evidence of symptoms that developed sometime before the age of 16 to 24, let's say. Even then, we're not going to apply a strict numerical criterion, as development continues until individuals are at least 24 to 30

years of age. Even at that point, as I've noted, ADHD could develop in people who have had... A significant brain injury could develop at any time in life, secondary to such injuries. We want to make sure that the symptoms of the adult are pervasive. As I've said, they occur in many settings, so we're going to ask about where these problems are and in what areas of life they are affecting you, to be sure that it isn't just one place. Then, we want to make sure that there are adverse consequences occurring; we call this impairment. So,

is it interfering with your home life, with your social life, with your work, with your education, with your driving, with your management of money, with raising children, or with living with an intimate partner, as in marriage? We're going to ask about all of those things, and we want to see that there are problems in at least two or more of those domains in order to be confident that the person has ADHD. Now, it's very possible for somebody with ADHD, who has a very high IQ, to go quite far in school, maybe even to get into

college or even to a professional school, before they begin to have problems in school. Nevertheless, their high IQ does not protect them from the adverse consequences of ADHD in other areas of life, such as getting along with others, holding a job, managing money, driving, and being predisposed to antisocial behavior, drug use, or addiction. So, although a high IQ can protect someone with ADHD from some of the educational adverse consequences, it can't protect them from the others. During this evaluation, we will also see if the adult with ADHD has any other psychiatric, learning, or developmental disorders,

what we call comorbidity. This is because, as I mentioned in my last slide, there is a high risk that the adult will have at least another disorder, and possibly two or more. As we've said several times in this lecture, we corroborate what the patient tells us through others who know them well and through previous archival records, like school records, report cards, driving records, and criminal history work history. Can we see a pattern in any of these histories that shows impairment? Have adverse consequences occurred? Then, of course, we need to rule out the possibility that the

adult might be faking their ADHD, what we call malingering or feigning ADHD. This is not very common in routine clinical practice, but there are certain parts of the population where, here in the United States, we are seeing this as a more common problem. One is college campuses; at our universities, if you have ADHD, you can get special accommodations, considerations on your exams, extra help in your classes, and maybe even access to medication to help you. Some students want these advantages even though they don't have ADHD, and because of the internet, they are able to quickly

learn what the symptoms are and then go to a university clinic and complain about having ADHD. Professionals who work for universities have to be very careful in evaluating students to rule out those who seem to be faking the disorder to get these advantages. One might also see this in criminal trials where someone has been found guilty and wants to have their sentence minimized. They may argue that they have ADHD and that they shouldn't be punished so severely because their ADHD explains why they got into so much legal trouble. So there's a tendency sometimes in criminal

courts for people to fake ADHD in hopes that it might get them a more lenient sentence. Many times when I speak about ADHD in the U.S., people come up to me and say, "Where was this when I was growing up? I've never heard of this; I don't remember anyone in my school or in my social life ever being diagnosed with this." Well, that's true. They may not have been diagnosed with it because, until the 1990s, it wasn't widely recognized that adults could have ADHD, but they did have it; they just weren't diagnosed with it. ADHD

has been with us ever since we have been humans. As we know, discussions of ADHD exist in the medical literature going back to the 1770s. So where were these adults if they weren't being diagnosed? Here are the various problems that we see these adults having, and this might be where they showed up. A sizable percentage of adults with ADHD are not taking care of their health very well; they have a propensity for obesity. Females have a propensity for binge eating, obesity, and bulimia. They're more likely, as a result, to develop dental problems, even dental fractures,

from their risk-taking behavior and their aggression, and they may even go on to have a higher risk for type 2 diabetes. We also know that they are more likely to have had accidental injuries of all types, so we would have seen them in the emergency room or in obesity clinics or eating disorder clinics. About 25% of them may have had depression, so a mood disorder clinic might be where they went. As I said, 15 to 20% of children and 40 to 50% of adult patients with ADHD have an anxiety disorder, so perhaps that's where they

were being seen for their anxiety, even if their ADHD went undiagnosed. If they went to an obesity clinic, evidence shows that 40% of people who go to weight loss clinics are adults with ADHD struggling to control their impulsive eating. As I've mentioned, women in particular may be prone to bulimia or binge eating disorder. I noted earlier that there's a greater predisposition to substance use and abuse, and it's no surprise that when we look at clinics for drug abusers, we find that about 40% of them would qualify for a diagnosis of ADHD. Forget these people are

more prone to antisocial behavior and law-breaking. So, let's look at our prisons. What do we find? One in four prisoners in the United States would qualify as having adult ADHD. If we look at adolescents who are in our Juvenile Justice System, it's 50 to 80% of them who have ADHD. Notice that even if they're not diagnosed with ADHD, they might be seen in various other clinics or within the justice system as well. As I've said, they're more prone to injuries, suicide attempts, self-injury of all types, and even vehicular crashes. Look at the emergency room, and

you'll see a lot more people with ADHD coming in because of accidental injuries. As we've pointed out, adults with ADHD have more problems in their marriages, peer relationships, finances, work, and so on. So, that's where you would have seen these people when you were growing up: people who were in marital therapy, who wanted help with social skills, who needed help managing their money and finances, and who may have needed help getting and keeping a job. As I pointed out, people with ADHD are likely to die younger. One reason you might not have seen them is

that some of them were dying early—twice as likely to die in childhood, four to five times more likely to die in adulthood by age 45 due to accidents, suicide, or homicide. Most recently, my own research shows that adults with ADHD who are not receiving treatment have about a 10 to 13-year reduction in their healthy life expectancy or total life expectancy. That's because of the accumulation of all their impulsive actions over time: their proneness to drug use, drinking, smoking, obesity, poor diet, and not exercising all eventually begin to add up to a reduced life expectancy. Again,

this can be changed if we will just treat the ADHD. None of this is cast in stone in terms of early mortality or shorter life expectancy. It's one reason why we want people with ADHD to be treated as early as possible, and it's never too late to get treatment and to change these risks. So again, where were these people when you were growing up? They were there; you just would have found them in these other pathways. They may not have been diagnosed, but they were certainly having ADHD in their adult years. Let's focus now on

the treatments that we like to use for adult ADHD. I think of these as falling into five areas of management. The first is to get a thorough, appropriate diagnosis—get well diagnosed and understand whether you have additional disorders or comorbidities besides your ADHD. So, diagnosis or evaluation is our first component. Next, get educated about your disorder. Read widely, watch videos like this, and read my books, such as "Taking Charge of Adult ADHD" or "When an Adult You Love Has ADHD." There are many other books on this topic. Go to YouTube; you will see many of my

lectures on ADHD there along with others. Remember, truth is an assembled thing. The more widely you read, the more resources you examine, the more accurate your understanding of ADHD will be. So don't just trust one professional, one book, or one website. Read widely, learn, and look for consistency in the information across these sources. Then we use medications. Over 80% of adults with ADHD will need to be on medication in addition to the other things we will do for them. No other form of treatment is as effective for managing this disorder as the ADHD medications, and

that includes complementary, psychosocial, or psychological treatments. They are only about one-third or less as helpful as the medications. So, that is why we often combine the medications with these other treatment components. Please think about medication if you're an adult with ADHD, because if you turn it down, you are turning down one of the most effective treatments we have. It would be as if you were a diabetic and told me you refuse to take insulin, or as an epileptic who doesn't want to take their seizure medication. You're turning down a very effective intervention. That's not to

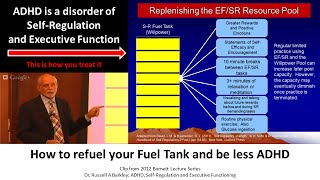

say that the medications do not have side effects; all medications have side effects. Those for ADHD are annoying to some extent but not life-threatening. The next component to treatment is to modify your behavior as best we can. We do this by helping you with cognitive behavioral therapy programs, mindfulness meditation programs, increasing your participation in exercise and physical activity, and getting you to rearrange your environment in order to change your pattern of behavior to be more helpful and beneficial. So, behavior modification is the fourth component of treatment. Finally, we like to rearrange your workplace, home, or

school settings to make them more conducive to your being able to function effectively there. For instance, breaking your work down into smaller quotas, taking frequent breaks, moving while you're working, even including squeezing a rubber ball, standing while you work, or going for a walk before you go into a meeting—these are all ways of changing your environment as well as your behavior in order to make it more likely that you can get the work done and meet the expectations of that situation. So again, the five components of treatment are evaluation, education, medication, modification of behavior, and

accommodations—changes to the environment. Now, within those five components, let's look a little more... Specifically at the things we recommend for adults, the first is that we counsel the adult about their diagnosis of ADHD, sharing with them all of the information I have shared with you today in this lecture. By doing so, we hope to bring you to a new view of yourself and of your ADHD. ADHD is a chronic medical disorder that persists in many people into adulthood and has to be managed using multiple means on a daily basis. It is exactly like diabetes, which

is why I call ADHD the diabetes of psychiatry, because it helps people understand the approach we need to take to treatment. The treatments we have cannot cure diabetes; similarly, the treatments we have cannot cure ADHD. But we do them anyway because we're trying to contain, maintain, and control the disorder to prevent the many other harms that will happen if we don’t. You know the harms from diabetes: heart disease, going blind, gangrene, infections, risk of amputation, vascular disease, and so on. All of these are things that happen, as well as early death, to people who don't

manage their diabetes, and the same can happen with ADHD. Remember all of the different domains I showed you that ADHD interferes with if it is not treated. So think of ADHD like diabetes, and you will understand what we have to do in order to treat ADHD: treat it using multiple methods on a daily basis to improve functioning and prevent harm. Now, the medications for ADHD that we have here in the United States are the stimulants: methylphenidate, which was known as Ritalin in earlier years, and the amphetamines, which people knew as Dexedrine back decades ago. More

recently, drugs like Adderall and Vyvanse have been added. There are many different drug names for stimulants, but they basically involve these two chemicals; it’s just that they may be formulated into very different delivery systems. The way that we take them and those different delivery systems keep the medicine in the body longer than the original immediate-release tablets of these medicines used to do decades ago. The next category of medicine we have in the US is the non-stimulant called atomoxetine. This is not a stimulant; it's a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. It makes more norepinephrine available in the brain,

whereas the stimulants are more likely to affect how much dopamine occurs in the brain and, to some extent, norepinephrine too. Other countries often only have methylphenidate and atomoxetine, but Western countries—particularly here in North America—have a much wider variety of medicines, including the amphetamines. Now, recently, about a decade ago, people discovered that drugs used to treat high blood pressure in adults, clonidine and guanfacine, known as Alpha-2 agonists, also had some behavior-modifying effects that might be helpful for managing ADHD, particularly impulsive, hyperactive, explosive behavior. So they've been reformulated into extended-release preparations for use now in ADHD here

in the US. So we have at least three kinds of medicines: stimulants, non-stimulants, and the Alpha-2 agonists. Besides these medicines and teaching you about ADHD, we also counsel you about ways to adjust to your ADHD to improve your life, to understand your ADHD better, and encourage you to own it. As we say, just like a diabetic has to understand that they are a diabetic, adults with ADHD need to own their ADHD because they won't do anything about it if they don't believe they actually have it. So sometimes we have to counsel them about acceptance of

the diagnosis, living with the diagnosis, and finding ways to succeed in spite of it. As I've said, we also help adults with ADHD make changes to their home and work life so that they are better able to function in those environments. Whether it involves recommendations about organization of their workspace, time management tips, using calendars, day planners, and computers to help with our scheduling and our to-do lists, all of these are ways to make people more accountable for the work they've agreed to do. One simple way of doing that is to make yourself accountable to others

more frequently for what you promise to do at work. You can have a colleague or a supervisor with whom you meet several times a day, discussing what you plan to do, and knowing that you have to meet with them later that day is more likely to help you stay on task and get your work done. I've already mentioned that we try to help adults with ADHD modify their behavior, and we do this through cognitive behavioral therapy. But in this case, it’s not the usual forms of CBT that we would use for depression or anxiety; instead,

this version of CBT focuses on those executive function deficits that lead to problems with impulsiveness, poor emotion regulation, time management difficulties, and difficulties with self-motivation. There are different programs available—at least three here in the United States—that have been developed and tested through research and shown to be beneficial for adults with ADHD. Manuals by Mary Solanto and Dr. J. Russell Ramsay are the more recent manuals that explain how this CBT should be done. Here in the US, we have a new profession that has developed over the past 20 years, known as adult ADHD coaching, in which

counselors, therapists, or other paraprofessionals have gotten some training in ADHD and how to help manage it. They will meet with you more often, text you, use Facebook, and use other social media as well as your smartphone to stay in contact with you frequently in order to help you cope with your ADHD and accomplish the goals you wanted to achieve that day or that week. Hopefully, this will become available in other countries as well. Not yet definitive, there is a growing body of evidence showing that teaching adults with ADHD mindfulness and meditation can be helpful for

them, particularly in managing stress and gaining more emotional control. Therefore, there are now new books published just this year on teaching adults with ADHD mindfulness and meditation. I think that this may prove to eventually be helpful—not for all the deficits that ADHD produces; it's hard for me to see how mindfulness meditation would help someone with time management—but it would help with emotion regulation. As I've said earlier, it's becoming increasingly evident in our research that movement helps people cope with ADHD symptoms. So, we encourage regular daily exercise, as well as incorporating smaller muscle movements during periods

of work or other sedentary activities. For instance, simply squeezing a tennis ball while you're working, standing while you work, or pacing back and forth at your desk while you work are ways of helping to sustain concentration and reduce the impact of ADHD in school or the workplace. Finally, because of all the health-related problems I've mentioned that go hand in hand with ADHD, including the risk for early mortality, as well as obesity and a shorter life expectancy, we encourage adults with ADHD to routinely participate in preventive medical care, that is, annual checkups and preventive dental care,

so that they don't let things get so out of hand that these become serious medical problems for them. Now, some adults with ADHD ask me if there are certain jobs that are better for an adult with ADHD, and the answer is probably yes. In my own experience working with thousands of people with ADHD, these are the kinds of things that we see about their work in which they find that they do better in their workplace: if they're allowed to work this way, allowing more movement while they work, not having to sustain their attention for too

long on any one thing, and having a job that's more exciting or stimulating, such as being an emergency medical technician, a fireman, a policeman, or a soldier in the military. If you're a physician with ADHD, working in the emergency room might be a good place for you. They seem to enjoy work that involves more hands-on interaction with materials, such as carpentry, plumbing, or being an electrician, a landscaper, a mason, and so on. Working with their hands and building things, or even working with computers and fixing them, are tasks they find to be more interesting. Jobs

that involve changing the workplace often, such as being a door-to-door salesman or someone who works as a videographer for a television station—who goes out every day and collects film footage of current events to show on the nightly news—are also appealing. These are all examples of situations that people with ADHD find to be helpful in coping with their disorder. Being more accountable to others, as I've mentioned in the workplace, having more flexible hours to determine when you start and when you end work can be beneficial. Adults with ADHD report that their best hours of concentration are

not the morning hours, as is typical with other adults, but rather the afternoon and evening hours. So perhaps allowing them to adjust their work schedule to when their attention is most optimal might be advantageous. Of course, jobs that don't require a lot of sitting still, sedentary activity, organizing long-term projects, planning things out, and so on—paperwork—are not very ADHD-friendly. The more frequently they can interact with others as part of their job, such as in sales work, the better. Having work that is broken up into small quotas with frequent breaks can also be beneficial. Targeting them to

a vocation that capitalizes on their aptitudes or strengths is crucial. Often, adults with ADHD are good at non-traditional things such as athletics, sales, being an entrepreneur, working with computers, dealing with other people, traveling, and so on. These are areas where people with ADHD may have strengths and better aptitudes for success. Of course, jobs that allow them to be a little more impulsive and expressive of their emotions might be better suited for them. Think about stand-up comedy, drama and acting, and the arts, such as dance—these might be fields where adults with ADHD would thrive more than

in alternative occupations. People with ADHD are often a bit more creative, especially if they have high intelligence, enabling them to generate more ideas and more unusual concepts. So, making them part of a creative team involved in advertising, for instance, could be a way of harnessing their creativity while keeping them in a group that helps them maintain focus. Here's a list of the various occupations I may have mentioned already, and others in which we find adults with ADHD having satisfactory careers and being able to achieve success. I'll just leave that for you to decipher. In conclusion,

adult ADHD is not a disorder of attention; it's a disorder of self-regulation. The brain's executive functions that are needed for self-regulation guide directed behavior and preparing for the future. Much of this has to do with poor inhibition and difficulties with other executive functions, such as working memory, self-motivation, time management, and so on. About 3 to 5% of adults in the U.S. have ADHD, making it a relatively common problem, and it applies to both men and women. The sex ratio is about 1.6 men to every woman, but women have ADHD too, and it can be just

as impairing. About 23% of the children diagnosed with ADHD will have ADHD into adulthood—maybe not severe enough to still qualify for a diagnosis, but they are still highly symptomatic, and it interferes with their lives. So, it's a very persistent disorder in most cases. As I've shown you, adult ADHD can adversely interfere with virtually every major domain of human adult life activity—from home life to work, to school, to friends, to marriage, to driving, to money, to health, and so on. Therefore, it's a very pervasive disorder in terms of its negative effects, which is why we need

to take it more seriously and make sure it gets treated well. As I've explained, the disorder is largely due to biological factors, such as causes within the realms of genetics and neurology. It is not a disorder that is caused merely by social problems, by sugar in the diet, by too much screen time, or by other ideas popular among laypeople that have no scientific basis. Treatment of adult ADHD, as I've argued, involves five components: an evaluation to get your diagnosis; education to learn about the disorder as much as you can, and to accept your disorder as

part of you; medications that can be very effective at managing your ADHD. In most cases, only about 10% of people with ADHD do not benefit from any of the medications we have available; learning to modify your behavior through cognitive behavior therapy; and focusing on your executive function problems can also be helpful. Additionally, making changes to the environment—what we call accommodations—can be beneficial too. So, I hope you've learned more about adult ADHD. In conclusion, you need to understand that despite the seriousness of this disorder, it is among the most highly treatable disorders we know of in

psychiatry. We have more treatments, particularly medicines, that do more to change these symptoms and help more people with the disorder than any other psychiatric disorder, including depression, anxiety, learning problems, and so forth. So, there's a lot of hope for adults with ADHD. If they can get treatment, they can lead relatively successful and meaningful lives. Thank you very much for joining me for this lecture today. I hope that you have found this information to be of use to you as you go forward and learn more about ADHD.

Related Videos

1:33:33

Assessment of ADHD in Adults: Methods and...

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

37,804 views

20:51

Mental or Inner Restlessness and ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

17,298 views

22:02

Why Dr Gabor Mate' is Worse Than Wrong Ab...

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

165,965 views

54:14

Perfectionism and ADHD | Thriving with Adu...

Help for ADHD

133,550 views

13:49

ADHD, IQ, and Giftedness

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

263,563 views

13:36

Should You Be Assessed For ADHD? Psychiatr...

Harley Therapy - Psychotherapy & Counselling

1,719,775 views

1:45:53

ADHD, EF, and Self Regulation

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

23,932 views

28:15

ADD/ADHD | What Is Attention Deficit Hyper...

Understood

9,918,686 views

13:47

This is how you treat ADHD based off scien...

Adhd Videos

4,369,021 views

18:55

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) Miscon...

Kati Morton

130,272 views

22:01

Sleep Problems & ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

41,072 views

59:39

2012 Burnett Lecture Part 1 Keynote Speake...

UNC Learning Center

29:23

ADHD Impairments in Interpersonal Lives 2009

CADDAC Centre for ADHD Awareness Canada

281,709 views

53:57

ADHD and ASD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

38,890 views

17:38

Loneliness & ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

50,657 views

8:56

Recognizing ADHD in Adults | Heather Brann...

TEDx Talks

1,084,188 views

1:02:37

6 Principles for Raising a Child with ADHD...

ADDitude Magazine

94,454 views

1:16:15

Modern Concepts of ADHD - Peter Hill

Gresham College

27,316 views

35:56

What are the Myths and Facts Behind ADHD? ...

TVO Today

97,787 views

35:13

Adult ADHD and Childhood Trauma

Patrick Teahan

1,561,163 views