Somalia, The Modern Pirates

1.15M views6379 WordsCopy TextShare

Best Documentary

For several months, from the Seychelles Islands to the Somali coast, Olivier Joulie went to meet fis...

Video Transcript:

The Seychelles, the end of September 2009. Southeasterly winds blow over the islands. It's the end of the rainy season.

A time when tourists stroll along the beaches and around the fish markets, while at the other end of the island at Port Victoria, about 30 French and Spanish tuna boats are preparing to set out to sea in an atmosphere of tension and stress. Since 2007, the Indian Ocean has become fraught with danger. Fear has a name here, piracy.

Every day, famine and poverty force desperate men to face the dangers of the elements and to attack ships sailing in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Around 100 such ships have so far fallen victim to the Somalian pirates. No ship is safe, be it a cruise ship, a giant oil tanker, or a tuna boat such as this one, the Playa de Bakio, which was attacked with a rocket launcher.

Few ships now dare approach the Somali coast. However, the tuna boats still come here. It's the season for tuna fishing.

There are just three military frigates to protect them. We're on the Indian Ocean on the Txori Toki, a tuna boat sailing under the Spanish flag. The only Frenchman aboard is Ronan the captain.

At the age of 52, he's beginning his 25th season in an ocean that in the past two years has become a no-go area. We're setting out with fear in our bellies if we have to be honest. The sea's huge, immense.

How is it possible with just three or four military vessels at most, to control a tuna fleet spread out over 1,000 or 1,500 nautical miles? If we put a military ship every 100 miles, which is not even the case, a simple rubber dinghy slips through the net. On deck, the men are preparing bamboo frames used to attract the fish.

Each one is equipped with a GPS buoy that the crew can follow and locate. The fishing here is miraculously abundant between August and November when a cold current mixes with the warm waters from the Horn of Africa. The Somali season, in fact, concerns everything out to sea off the east coast of Somalia.

The whole East African coastal zone becomes abundant very quickly and so it attracts shoals of fish and tuna to this area. Many Spanish tuna boats are tempted to join them. That's what happens until there's an attack.

The most reckless then becomes the first to take flight. That's what happened a few weeks ago when three Spanish boats were attacked. All three then changed course to the east because they were really scared.

We could go to this area here, where we'd be a long way from the acts of piracy, but we wouldn't catch very much, as the water isn't rich at the moment, so it's not worth going there. We might as well stay in the harbor, it's much simpler. Since the pirate attacks began, Ronan's eyes never leave the radar.

Astutely, he's carefully recorded the details of each Somali attack on his computer. All the boats you can see correspond to attacks by pirates. On the southern part of the Seychelles, the southeast part of the Seychelles, the western part between the Seychelles and the Somali coast, from Kenya to Somalia.

In the northern part of the Seychelles, we haven't indicated the latest attacks. There have been three, no, four in recent weeks. Are the boats equipped with weapons?

Weapons? All the pirates have weapons on board. Up until now, we haven't seen any attacks without weapons.

Do you know what kind of weapons? Kalashnikovs and RPG rocket launchers, grenade launchers. Systematically, they fired at the boats.

Even if the boat is stopped, they fire at it. Arrival in the high-risk area is scheduled for tomorrow morning. To get on board the target ships, the pirates use small, swift craft, skiffs, towed out to sea by what's known as a mothership, a larger vessel carrying fuel and supplies.

At the stern of the Txori Toki, the crew are setting up a fence as best they can, an illusory protection to prevent the Somali pirates from taking over their ship. At sea, even the rules of navigation have changed. We've never seen anything like it, never.

There are no other solutions. We're not respecting the regulations but every ship is doing the same. Apart from the merchant ships further out east.

Every ship sailing now like us is sailing without navigation lights. At least we know that these small boats, maybe seven or eight meters long, and there are quite a few of them, won't be able to see us. Seeing us on the radar is impossible.

They just can't see us. At least on that score, we're all right. I feel a lot safer at night than during the day.

In the early morning after sailing all night, we finally reached the buoy Ronan located the previous day. We're here, Forty south, 40 minutes south, 50, 30. Always before we cast, we always look at the radar.

When the chief decides whether we cast or not, we check that there's nothing up to 32 and 48 miles. Then the chief will say cast, and we'll release the net and we're ready. -Ready?

-Okay, ready. Ready, everyone ready. Cast away!

In just a few minutes, the ocean's clear waters fill 1,800 meters of net. We're at the limit of Somalia's territorial waters. Two hundred miles away, the coast and the pirates' villages, the skiffs' point of departure.

On the bridge radar, unusual echoes draw Ronan's attention. Usually, it's trawlers, because there are several trawlers in the sector, but you can never be sure. It's coming from here and that one from there.

It stopped. They're tuna boats. Look, they're moving quicker, there's no problem.

As you can see here, we've completely stopped. For two hours or more, depending upon the quantity of fish in the net, it could be more or less. If there's more fish, we've stopped for longer.

The more there is, the more vulnerable we are to any attack, from pirates. If I see an echo seven or eight miles out, approaching, I'm entitled to wonder if it's pirates. Am I going to wait for a definite visual contact and say, right, it's pirates who have grenade launchers, before I do anything?

The Atalanta military says no, it's not pirates. You need to wait for confirmation. Maybe we have to wait with our arms folded for them to come on board to say there's been an attack.

At this point, the Txori Toki and its crew are anchored by a net descending to 250 meters from the seabed. Their survival now depends on Operation Atalanta, the European anti-piracy mission set up in January 2008. It is in Djibouti, a small state with 800,000 inhabitants, at the entrance to the Gulf of Aden, that Operation Atalanta has established its base.

For the world economy, these shipping channels represent huge stakes. Every year, more than 20,000 merchant ships pass through, including the supertankers that transport 30 percent of all Europe's oil supplies. Operation Atalanta involves a dozen frigates in the Gulf of Aden, entrusted with the protection of world trade vessels, and just three to survey a zone in the Indian Ocean five times as big as France.

This morning the sun lights up the shipping lane and the cargo ship so close together, escorted by warships. We're onboard the French patrol plane Atlantique Deux, one of three such surveillance aircraft assigned to Operation Atalanta. Its mission is to detect any suspicious vessel that comes too close to the shipping channel.

In the back of the plane, officers keep their eyes glued to their screens. Using radar and sonar, every square inch of water is examined. Can you transmit your echoes, mate?

Once a target is spotted, the plane dives to 30 meters above the sea, but keeping out of range of potential rocket fire. Queue the photo. The photo is immediately analyzed by a tactical coordinator and his assistant.

In just a few seconds, they have to evaluate the risks. Can you confirm from the photo that there are three skiffs? Zoom in a bit to see if there's a motor.

Zoom in some more. Okay, there are three skiffs. Shift the image a bit.

Three skiffs, two people between the skiffs. Some barrels. Can you confirm there's no fishing equipment?

No, no motor, no fishing equipment. We'll classify it as suspect. Suspected of holding pirates, the boat is immediately pursued by an Atalanta frigate.

It will be boarded half an hour later. In the Gulf of Aden, we hope to get results this year because we had a lot of pirate boats last year. This year we've seen four pirate boats off the Somali coast, off the camps.

Last year, at about the same period, we had more than 15 boats. We can consider that the coalition's current mission is effective. After the Somali basin, the other zones are much more extensive but we're familiar with the tuna boats' positions.

We know exactly where to find them, we know which zones to cover. Obviously, we can't cover such immense zones, but with the knowledge we have of the ships to protect in the zone, I believe we can still be quite effective. The morning's second mission is to survey the Somali coast, visually once again.

To do this, they need to get close. Just off to the sandbank, there's a sandbank. We can see a lagoon.

Then there's a village. Okay, I've got a visual. We're now very close to the coast and can see the pirates' bases.

Here, we can see the details of the town quite well. We can count the skiffs and estimate the amount of fishing activity because we can also see fishing vessels. There are boats between ten and 15 meters in length.

We have the info we're looking for, the movements of vessels along the coast and we can use that information. In 2009, more than 90 percent of the pirate attacks in the Gulf of Aden failed. In the Indian Ocean, the pirates have a much freer hand.

Far from the protection of the Operation Atalanta frigates, the Txori Toki is still fishing. With its net deep in the water, the boat's been immobilized for three-quarters of an hour. It's at times like this that the risks are highest and danger is not far away.

The France Ter apparently encountered pirates last night. They managed to drive them off. They think they were pirates.

A ship put down three small craft. We're wondering who will be the next to be attacked. Who will get captured?

We've just heard that a cargo ship skipper was killed over by Mogadishu, and we're here, fishing for tuna. A strange enemy indeed, these pirates. Invisible yet omnipresent, who can suddenly appear behind the crest of a wave.

On deck, the men know they are prisoners of their nets, and nothing is planned in the event of conflict. The procedure, if we should see a small fast boat approaching, with the net in the water, the only thing would be to cut the cables, to let the net go, and to escape. It's always better to cut the net than to get captured.

It's our lives at stake because no one knows what might happen. Certain Spanish ship bosses have not resisted the pressure. In just a few months, a dozen or so have left the Indian Ocean for the haven of the Atlantic.

In the hold, the fish slide directly into refrigerated vats, and the catch is weighed. Almost 180 tons this morning, not a lot for the season. According to the director of one Spanish company, the biggest one, they will be 40 percent down on earnings this year.

Since the start of the Somali season, in early August. On board, the sailors are taking it hard. Their pay depends on the catches, and in these conditions, it's impossible to fill the holds.

They absolutely don't take us into account. Absolutely not. I'm telling you they're waiting for something serious to happen to react.

They're waiting for a tragedy or I don't know what. Before then, we'll get nothing. We get the impression the government isn't interested in us.

The Spanish government has completely abandoned us and the public isn't interested in sailors. They prefer to send soldiers to Afghanistan or somewhere, rather than here by our side. They should come here.

They'd understand then, how we suffer every night, every day, thinking about it all the time. At year end, they'll be counting the money our suffering has provided for their profits. The lack of understanding is total.

The Spanish government and the shipowners have been holding each other responsible for the crews for months. I think the owner believes that private security companies aren't competent with the resources they have. If something happened on board, the shipowner would be the only one responsible, not the government.

What the government does is to allow the use of private soldiers. Above all, it doesn't want the responsibility. The shipowner doesn't want that.

He says that the flag is Spanish and that the government should put soldiers on board. The government is against this, so we're here with nothing. For the moment we have neither one nor the other.

The only thing we do have is a frigate and a plane that we have no news of. We haven't even seen it for a month and a half. Nothing else.

I don't understand it either. It's political. We have sailed more than 2,000 kilometers with no sign of a frigate.

Our distant protector, Operation Atalanta, is keeping a low profile. There are two more months to go in the Somali season. As Ronan continues his route towards ever-increasing risks, his French colleagues are enjoying a rather calmer voyage.

We returned to the Seychelles. In France, shipowners have organized firm action. Since last July, about 60 marines have been posted to the tuna boats.

The French have understood that their security has a price. I want one guy to stay in position and two to go and help keep loading. You follow me.

Steven is used to such high-sea missions, although this one is rather different. It's not France's interest at stake here, but the shipowner's. These are the weapons that will be used to guarantee the sailors' safety and ours too.

What does the crew think about having weapons on board? They'll get used to them little by little. The uncommon presence of the marines has necessitated various changes on board, and the slightest space has been put to good use.

The marines are preparing to spend four weeks at sea. They will share the same cabin, usually reserved for fishermen, and the weapons will be kept under constant surveillance. At the age of 40, Christian is one of France's youngest fishing bosses.

He runs the 80-meter-long Via Mistral and its crew of 26. The marine reinforcement unit, for him, is a form of life insurance. It might seem odd to go to work with a protection squad with bodyguards, but we haven't found another solution for the moment.

As long as the piracy goes on, I don't know how we can solve the problem. Everybody feels safer. We're not authorized to film the heavy weaponry, but we know that on board is a machine gun ready to fire deterring bursts at a range of over 1,000 meters.

The defence strategy is being kept under wraps too. Military secrets, we're told. We won't explain the organization, we want to keep that secret.

We're capable of reacting to a huge range of situations, both short and long distance. We're here primarily as a deterrent. Subsequently, if any piracy action requires a continued reaction, we have the necessary resources to repel them day or night.

We leave the Seychelles behind us. With a veritable arsenal to protect him, Christian can now fish where Spanish boats don't even venture. The shipowners confirm they are paying the French army for the protection teams.

According to our estimates, the cost is around 2. 5 million euros for nine boats for four months. The protection enables the French boats to catch more tuna than the Spanish.

Less fish means less turnover. The expenses are the same. You leave with a boat and a full tank of fuel, you sail for 50 days or so, but you don't fill the holds with fish.

Your expenses have gone up in smoke. It's a business like any other. We can no longer stay on the Via Mistral.

Our presence is no longer desirable. However, the facts are there. France authorizes soldiers to work for private companies.

An unorthodox war fought without witnesses and any questions. We're picked up by the Txori Argi. On board, the crew inform us that a Spanish tuna boat has just been attacked.

At seven o'clock this morning, we were informed that Alakrana was in the hands of pirates. As of eleven o'clock, it set course for Somalia. Heading 312 at five knots.

The first signal we received on the frequency and it was the only transmission was: "We are under attack. We are under attack. " Since then, they have not responded to the radio or the telephone.

That's it. We knew it was going to happen. What we didn't know was where and when, but we knew it would happen.

Everyone knew we were exposed. Ultimately, it's happened. I hope it's only about money.

I hope there won't be anyone wounded, no one missing, no problems. We have to understand that on this boat, which is quite a special boat, there were 42 crew members, I believe. Forty-two crew members, each one with their own family.

Imagine how worried they are right now. I talked with the boss of the Alakrana about this problem a month ago, and he said: "Santi, it's okay, it's my last trip. " "I've got one month to go, one month.

" "When I get back to port, I'll go home and never come back. " "Another 20 days and I'll be at home. " Instead of going home, he's in Somalia looking at pistols, Kalashnikovs, and grenade launchers.

The atmosphere is grim when we disembark at Port Victoria. Santi should be heading back to Spain for a two-month holiday, but first, he has to hand over to Norbert, a French ship boss from Concarneau who can barely imagine what lies ahead. Santi, how are you doing?

Good, but we have problems with the pirates. Yes, I heard yesterday. Any more news today?

No, there's a frigate not far away to help them. The news yesterday was that they're 100 miles off the coast. People are saying that the crew's all right.

That's important, we just have to wait for them to be freed. We'll see with the office on Monday. The office was saying that the owners had made a decision.

All the boats must fish east of the 60th parallel. No possibility of fishing elsewhere except the French boats with the soldiers on board, but not us. With the Alakrana problem, the Spanish government might think differently.

The Txori Argi wakes up the next morning to more bad news. Norbert and his captain learn that three skiffs had attacked a cargo ship leaving the Seychelles. The sailors immediately try to learn more from the Atalanta authorities.

We're just about to head out to sea. We want to be sure of the position and if we can head out towards the east. Okay, thanks a lot.

They've looked. They've checked the Seychelles perimeter and have only detected one boat and two other small craft. Did they check east and southeast?

Anything else? Very little to the southeast and nothing east. -They think it's all right.

-They think? The anger is mounting. Once again, operation Atalanta is demonstrating its ineffectiveness.

The pirate boat has not been located and Norbert decides not to move. He immediately informed his boss in Spain. We don't know where it is today, or what route it was taking.

We don't know how many they are, and they want me to leave port? I can't go to the north or the northeast, to the east, I don't know. Tito, it's just not possible, it's not possible.

I won't risk my life and the lives of my men. It's too serious. It's Norbert's third day in the harbor.

Under pressure from the shipowner, preparations continue, but the news is not good. -That's the position of an attack, there. -That's yesterday's position.

It's the same position as the cargo ship before. Is it the same attack or another one? Another one.

The information is dated today. October 6th. It happened yesterday evening and this morning.

It's a boat of about ten meters like the pirates in the photos. The boat is a bit over ten meters with people guarding oil drums to hold out for a long time at sea. Yes, like the photos of the boats before.

We don't trust the owners any more than Operation Atlanta. We have no confidence in them. With all the information we're getting, we don't trust anyone.

There's total confusion. There's false, mistaken information. It's not right.

There's no organization. Absolutely none. Despite the deadlock, the fear, and the uncertainty, Norbert has no other choice.

There's nothing to encourage us to go out, but there you go. There's a lot of pressure from the owners and so on. We have to go out.

They have to leave Seychelles to the east and at all costs, avoid the Somali basin. Future events will prove him right. A week later, two French tuna boats, the Drnek and the Glennon, will be attacked north of the Seychelles, less than 30 kilometers from the position indicated by Atalanta.

For over a year and a half, the Spanish fishermen have been the poor relations in Europe's anti-piracy plans. On the Somme, the French army's flagship in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, Rear Admiral Nielly explains that Operation Atalanta simply has no vocation to protect the tuna boats. Obviously, the military resources of the European operation intervene when fishing boats are attacked.

It's part of their mission as security providers in general, but it's not a specific mission to protect the fishing fleet. Despite the presence of three frigates and two reconnaissance planes off the Seychelles, Norbert's suspicious boat was never found. Very probably, there have been several groups of boats in the last few days, with mother skiffs and attack skiffs positioned in the same zone on the fishermen's route between the Seychelles and the fishing zones.

We try to locate them, but they can move very quickly. If there are gaps in the detection process, we can lose a mothership or the skiffs. Even with the maritime patrol aircraft.

If their search zone is a few tenths of degrees off, they won't come into it. The pirate boat's mobility and the sheer size of the ocean are overwhelming problems for the Atalanta officers, and the pirates know it. What happened is that the watchman who was in position here, saw, around midnight, a first skiff.

Between 150 and 200 meters, a beam of the ship. Very quickly, a first shot was heard. Following this attack, the Somme immediately set off in pursuit of its assailants.

Five pirates were arrested after an hour's chase. Their boat was taken on board the frigate. It should be known that when we arrested these people, they were aboard skiffs without food and water, with no fishing nets and no weapons.

There's no real tangible proof. Without proof, no legal proceedings are possible. A few days later, the Somali pirates will be handed over to the authorities of Puntland, a region in northern Somalia.

Who are these men? What do they think about the military forces in the Gulf of Aden in the Indian Ocean? Who hijacked the Alakrana?

We decide to head for Somalia to find the answers. A vast majority of the pirates come from Puntland. Almost a million people live in Bossaso on the northern Somali coast.

Regarded as the hub of the region's activities, the city is a focus for all manner of trafficking. Wood and spices, as well as illegal immigrants and pirates. The five pirates have been transferred to the main prison here outside of town.

Concerned about maintaining cooperative relations with the Western world, the Puntland authorities allow us to visit the inmates. The orders are that you film this prison only briefly inside and outside and that the meeting takes place in this office. I'll have the prisoners who were brought here released.

The five men all come from Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. They're aged between 20 and 30. The French told us we were 200 miles from the coast.

It's not possible we were that far out. Fuel supplies were only to cover 50 miles. As we don't have navigation equipment, it's possible to make a mistake, but not by as much as they say.

We haven't done anything illegal. We're suspected of crimes that others have committed. We're not pirates.

When they took our boat, they handcuffed us and looked everywhere for weapons and pirate equipment. They found nothing, only fishing gear. They told us we were suspected because of the 400 liters of fuel they found on the boat.

We haven't been tried. When we came here, they told us of our sentence. You are sentenced to five years in prison because of the fuel.

That's all we know. We have no more information. We are very surprised by what has happened to us.

Excuse me, sir. There's something that needs to be corrected right away. They were tried and then sentenced to five years in prison.

That has to be said. What the pirates don't say is that they systematically throw their weapons overboard as soon as they see a frigate. Almost 80 Somalis, all accused of acts of piracy, are incarcerated in this ancient, decrepit prison.

Forty or so are squeezed into a cell of barely 20 square meters, with no water and no electricity. The Puntland authorities do not require proof to sentence pirates. Jail time can reach 20 years.

It's a way for the local government to gain favor with Operation Atalanta. As day breaks, we leave Bossaso and head for Garowe, the administrative capital further south. The French are no longer welcome in this region since Somali pirates were imprisoned in French jails in 2007.

If you're recognized as a French journalist, the families of the pirates held in France may want to capture you and use you as a means of exchange for getting back their men, who are currently in French prisons. Why are there so many pirates in Garowe? That's because it's the capital and those who sympathize with them are many.

Our driver has promised to set up a meeting with one of the pirates who defy the international military forces in the Gulf of Aden. We meet him that evening in a hotel. His name is Abdi Razak.

He is 28 years old and has been working as a pirate for four years. Abdi claims to have hijacked four boats in his career. There's no question of revealing our true nationality.

He believes we are Canadian. We begin the interview by asking him what he thinks of France. The French, we will kill them because they've killed some of ours.

We won't have any scruples about that. If they capture you, they either kill you or throw you in prison. What do you think about the military ships sailing out to sea?

The military ships are very present in the zone, but they can't do anything unless you're caught red-handed with weapons. On the other hand, if you're caught with weapons, then you've got problems. Whenever we see them coming, we get rid of the weapons and avoid any trouble with them.

Is it not too dangerous? What danger? It's our choice.

Life is tough and dangerous here. We're in Africa, there's no work. The truth is, it's less dangerous being a pirate than a soldier.

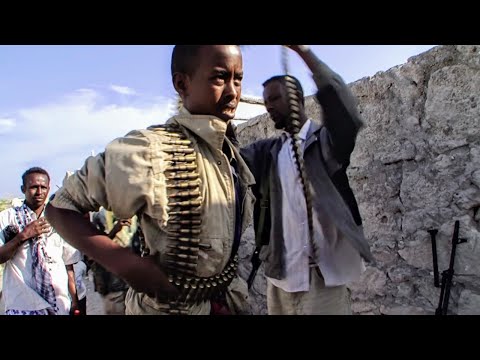

In reality, it's an easy choice to make. What other future is there for these young Somalis apart from the militia and piracy? What can they hope for in a country that's been at war for 19 years?

Somalia in the 21st century is a country bled dry, ravaged by clan wars, poverty, and oblivion. We hear that the Spanish tuna boat, the Alakrana, is at anchor a little further south. Ten days have passed since it was captured.

To get closer, we head for Galkayo, a town in central Somalia, and an obligatory stop on the way to reach the coastal villages. For the Ukrainian pilots who fly us there, Galkayo is a town beyond the law. What's it like there?

Oh my God! Ask the others. It's really bad.

Bandits. Pirates and bandits. When we get there, you come back with us.

There's nothing you can do there. Nobody works. They only know how to steal and fire guns.

Now you're going to land there. You can see for yourselves. They spend their days with machine guns and automatic weapons.

Nobody works. Apart from stealing and shooting, they do nothing else. Why, I don't know.

We're coming in, you'll see. We're met at the airport by Ali, a freelance journalist who'll be our interpreter on the journey to the Alakrana. At our first briefing, Ali explains the tension in town.

There have been confrontations between tradespeople and the local Puntland police. It went on for several days. The Puntland police tried to destroy buildings that were on their territory.

The tradespeople from Galmudug refused. The fighting began like that. It was very violent.

The death toll has reached 12. We enter Galkayo. It is here that tensions among the tribes come to a head.

The town is cut in two. The northern sector belongs to clans from Puntland and the southern zone to the Hawiye, a tribe originally from Mogadishu. South Galkayo was the beginning and capital of the self-proclaimed Galmudug state.

Strolling in the streets is out of the question. Every foreign visitor is under tight surveillance. Twenty or so men armed to the teeth are there to protect us.

The stifling heat in the hotel only adds to the day's oppressive atmosphere. The soldiers are tense. Since early morning, a meeting has been taking place between local leaders and a federal police chief from Mogadishu.

For several months now, certain Somali tribes have decided to join forces to fight their common enemy, the Shababs. These formidable Islamist soldiers, reputed to be close to al Qaeda, are on the point of gaining control in Mogadishu. Children have been conscripted by force, women raped, and seized from their families.

They say that the combatants of Islam need wives. When we ask them why they act this way, they say that all means are allowed to support the Islamic cause. As evening comes, the Shabab response is immediate.

Two grenades explode in the hotel, followed by gunfire. A dozen guards are wounded. Please, listen to me.

Please, listen to me, stop the camera! The next day, the town has a different face. Armed men patrol the streets around the hotel, while heavy artillery and an anti-aircraft vehicle have taken up position on the main street.

The militia seemed far from confident. We have a meeting this morning in a hotel room, out of sight, with Awil Roble, who will become our guardian angel. We tell him what we intend to do.

We want to go on the Spanish boat. They want to get to the Spanish boat. You'll need to get in touch with one of the members of the pirate group.

I will see. Awil promises to contact one of the military chiefs responsible for hijacking the Alakrana, a well-known warlord who has called himself Aden Law. We first have to reach a fishing village on the coast.

The pirate groups meet here after a boat has been captured. Night has fallen as we leave Galkayo. The journey over rough, sand-swept roads takes more than ten hours before we reach Hobyo, one of the newer piracy strongholds.

When we get to the beach, a surprise awaits us. Until now, no foreigners have come here. On the horizon, we see the bulky outlines of three steel monsters.

These ships are Ukrainian, Chinese, and Thai. Inside, the crews have been held hostage by the pirates for months on end. We're in Hobyo now.

The town is largely controlled by the sea pirates. Recently, they came here in large numbers. They come from several tribes and several different places.

The boats off the shore there were captured in different places. They brought them together here. On the beach, 20 or so skiffs are waiting to head out to sea on another attack mission.

We've seen enough. Awil is afraid our presence here will stir up the local population's wrath. We have to present ourselves to the village authorities.

The tiny sand-trapped village now houses some 3,000 people, deprived of almost everything, schools, water, and healthcare. The pirates enjoy relative peace here and the local youngsters make easy recruits. They're docile and have nothing to lose.

The village elders meet us in the courtyard of the only hotel. They want to explain their problems. The problems are out at sea.

The fishing by the big foreign boats destroys the maritime flora. They plunder our natural resources and the fish are gradually disappearing. Our fishermen, with their simple nets, don't have any way of competing, and so they become increasingly poor.

In addition, foreigners sometimes throw their waste into our waters. The locals are forced by hunger into becoming pirates or bandits. The consequence is that prices go up.

Today, only the pirates can buy things. For the others, it's difficult. Life has become too expensive.

Suddenly, a man interrupts our conversation. Careful of this white man. Please, be quiet.

Be careful of these people! -Let us talk. -They'll drop bombs on the towns!

Tell him to shut up. Beware, he's a spy, he's a Secret Service officer! The village chiefs decide to leave the meeting.

We are no longer welcome. Some talk among themselves about the possibility of taking us hostage and try to bribe our interpreter. In just a few seconds, we've become a potential financial asset.

Later, under tight surveillance in our hotel room, Awil suggests we meet a young villager, a member of the security team on the Alakrana. After two weeks on board, he's spending two weeks on land. The hostages are kept together in a particular place on the boat.

It is forbidden to talk to them or have any contact with them. They're locked up and never get out. They're not allowed to move around.

No one can get in touch with the boat. Only telephone calls between the shipowner and the pirates are allowed. Either you give us the ransom we demand or the position remains the same.

No contact will be tolerated and you should know you're the first people we've spoken to. As we talk, we realize that our Canadian cover story has been blown. Tell him that the French use journalists as spies.

How can I be sure that you're journalists? He could have had other jobs before. He can use his press card to do other jobs.

What proof do I have of what you say? I have nothing more to say to you. At that precise moment, we realize that we're not going to board the Alakrana, but Awil had promised to get in touch with Aden Law.

The pirate chief agrees to talk to us by phone. We do not choose the boats we capture. That one was in Somali waters.

Tell me, Aden, it's said that this boat wasn't in Somali waters. How come you captured a boat outside the zone? You should know that this boat, firstly, operated inside our territorial waters.

It was afterward that it left. Even if this boat wasn't there, many other fishing boats and merchant ships come in illegally. These waters belong to the Horn of Africa.

There are warships in our territorial waters. We also have to put up with pollution. Before any discussion, these ships must first leave the zone.

Can you tell us about the hostage situation? Are they well? They are all very well, they're in good health.

Have the hostages had any contact with their families? No, they are hostages that we are holding, they're prisoners. The team of journalists with me would like to meet the hostages.

Can we have permission? If these people insist, they will end up before our committee. He says that if you go on the boat, they'll take you hostage.

They won't leave the boat. That's for sure. Seeing our disappointment and to avoid losing face, Awil explains why no journalists have ever boarded a hijacked boat.

Every pirate believes that a wanted notice has been put out for him. They've become very wary. Every pirate believes that when a journalist interviews them, they'll immediately become a target.

As if a GPS device could locate them and identify them at any time. They think they'll be caught anywhere they go, and their pictures will be displayed everywhere. Ten days after leaving Hobyo, we learned that the captain and crew of the Alakrana had been freed in exchange for a ransom of 2.

8 million euros paid by the Spanish government, the highest sum yet obtained by the Somali pirates. The seizing of the Alakrana was traumatic for Spain. The Spanish tuna boats finally finished their Somali season accompanied by mercenaries.

The French military operation proved its worth. The French marines repelled three attacks by pirates. In 2009, the Indian Ocean was the scene of 200 pirate attacks.

The region has never seen so many such attempts.

Related Videos

52:49

Modern Pirates | Menace On Africa Coast

Best Documentary

11,650,189 views

52:03

Somalia: A Country in Free Fall

Investigations et Enquêtes

2,592,002 views

54:37

Boko Haram: Black Terror in Africa

Best Documentary

5,821,869 views

51:56

Libya - The comeback of Saif Al Islam Al G...

DW Documentary

531,408 views

57:05

Syria: the Legions of Holy War

Best Documentary

1,123,836 views

52:51

Niger Delta, the war for crude oil

Investigations et Enquêtes

3,922,696 views

42:46

No-Go Zones - World’s Toughest Places | Gh...

Free Documentary

13,722,004 views

57:54

Pirate Hunting: Meet the Counter-Piracy Ta...

ENDEVR

11,627,715 views

50:49

Colombia-Venezuela, on the border of drug ...

Les Routes de l'impossible

14,224,754 views

55:52

The Yugoslav wars: Arkan's Legacy in Serbi...

Java Discover | Free Global Documentaries & Clips

176,547 views

1:38:46

From Cape to Cairo by Bike | Free Document...

Free Documentary - Nature

5,360,950 views

51:12

The Gangs of Papua New Guinea

Best Documentary

2,393,820 views

1:38:15

DEEP SEA FISHING - Hard Work On The High S...

WELT Documentary

17,741,795 views

58:49

Yemen's Hidden Agony

Best Documentary

1,445,585 views

18:17

Afghanistan: Inside the Taliban's Emirate

Joe HaTTab

7,429,093 views

25:50

Liberia: A fragile peace

Investigations et Enquêtes

1,606,945 views

44:25

Mortal Combat (Full Episode) | Animal Figh...

Nat Geo WILD

16,136,002 views

48:09

Black Ops Special Forces: Operation Certai...

Best Documentary

1,244,459 views

30:43

The Rise and Fall of Somali Pirates

Johnny Harris

2,572,479 views

51:05

Madagascar: attacking the Red Island | Roa...

Les Routes de l'impossible

16,053,989 views