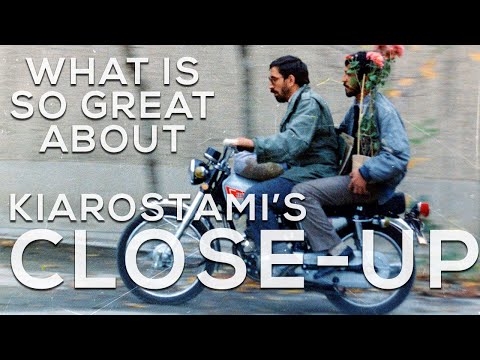

What's so great about Close-Up? (Kiarostami, 1990)

58.73k views3661 WordsCopy TextShare

Plan-Séquence

A study of Close-Up (کلوزآپ ، نمای نزدیک), a1990 Iranian masterpiece, often highlighted as one of t...

Video Transcript:

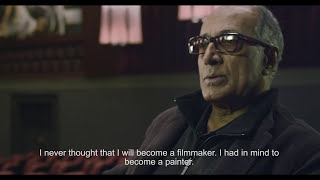

Abbas Kiarostami was an Iranian film director that is regularly featured on lists purporting to comprise the greatest filmmakers in the world. With a high stature among cinephiles and a career full of plentiful international awards, including a Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1997, Kiarostami can rightfully be considered one of the most representative authors in contemporary cinema. Notwithstanding the criticism of his work in his homeland, both during his life and still existing today, with some critics labelling him as “exotic” and charging him of “catering to Western audiences”, or just qualifying his austere film method as a “weakness”, as if stemming from lack of talent, instead of a deliberate aesthetic choice, he is universally seen abroad as a masterful artist with a singular sight.

Though the endearing “Where is the Friend’s Home? ” was his first film to make waves abroad, amassing several prizes at the 1989 Locarno Festival in Switzerland, it was “Close-Up” that actually shot Kiarostami into international recognition. The follow-up to “Where is the Friend’s Home?

” was supposed to be a project called “Pocket Money”, that had pre-production already underway when Kiarostami read an odd piece of news that caught his attention and then decided to postpone the project, coming up with a different idea based on that article. In it, a story was told of a man caught by the police called Hossain Sabzian, which had been accused of fraud, after deceiving a family belonging to a Turkish speaking minority in Iran, by posing as famous director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, allegedly with the intention to rob them, supposedly borrowing money at some point and taking advantage of them by pretending to plan the shooting of a film at their house, going as far as even directing rehearsals on it. “Close-Up” then follows the trial of Sabzian and makes use of re-enactments of key moments with Sabzian himself and the defrauded Ahankhah family members, a much unusual, indeed unique approach, that engrossingly keeps the spectator intrigued and fundamentally guessing the credibility of both the visual and audio aspects of the film.

One is drawn closer and closer to the film, only to have the authenticity of its framework and presentation being questioned with increasing scepticism. At the same time, purely on a narrative level, things aren’t also exactly as clear-cut as they were implied in the beginning and Sabzian turns out not to be a regular con-man, with Kiarostami probing deeply into his psyche and the possible origins of such peculiar case, exploring potential emotional or societal roots, opening up a line of inquiry to study the then current situation in the country. Effectively, “Close-Up” has all the ingredients of a courtroom drama and documentary feature, but that doesn’t stop Kiarostami from taking an active role, though unexpectedly not by dogmatically taking the side of the accused underdog, but going as far as grilling him in court, at times more incisively even than the judge, for the sake of getting to the bottom of the actual root problem.

Nor does he display the downtrodden in an uncritical, or only positive light, but actually gives room for the charged individual to either condemn or salvage himself on his own, the final verdict being attributed by the audience viewing the film. Initially, Kiarostami first had to share the story with Makhmalbaf, to check if he was willing to get on board, and after his approval, both went to visit Sabzian for a preliminary interview. Only then did they went to the Ahankhah family, but not before having to prove their authentic identity, given their previous trouble with Sabzian, as they demanded to see both men’s credentials.

Unlike Sabzian, who readily agreed with the project, members of the Ahankhah family were initially reluctant with the proposition, for as anyone will guess, the former had all the interest to substantiate and provide a motive for his actions, while the latter were disinclined to participate, as this would expose their naivety and mistake. However Kiarostami, certainly with the help of the real Makhmalbaf, managed to convince everyone to join the project, including the actual judge, that fortunately turned out to be a great fan of cinema and was particularly fond of Makhmalbaf’s films, to the point of achieving the delay of the trial for a better placement within the film’s schedule. “Close-Up” is a little peek into early 90’s Iran, tackling an unusual story in an unusual format, that reflects much of what was happening and what was felt as an Iranian person back then.

In the film, one perceives how cinema, the most popular means of entertainment in the country, was seen as a vehicle for attaining fame in a quick fashion, as well as power. Up until the Islamic Revolution, filmmakers were regarded as educated, albeit cheap entertainers, but now they are looked up to, regardless of coming from a privileged family and status, with Makhmalbaf serving as an example of the opposite background, as examples and stars worthy of admiration. Though nowadays that may not be exactly so, since perhaps one probably needs to earn some international award before being acclaimed, after Kiarostami and Farhadi’s recognition abroad, and considering how politicized the role of the filmmaker became, back then the fascination, however, derived from not just because of their ability to craft historical epics and grand melodramatic love stories, but also because, as Sabzian discourses so eloquently during his trial, they are able to touch the hearts of people by exploring their condition and stories that are near to them, the hardships, injustices and tragedies of ordinary folk, cases in point being Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf.

Issues such as poverty, unemployment, alienation, aimlessness and hopelessness, had been touched upon in Sabzian’s favourite fim, Makhmalbaf’s “The Cyclist”, and are highlighted and examined both through Sabzian and the Ahankhah family alike in “Close-Up” as well, left out in the open to be discussed by the cinematic audience. Even the reporter Farazmand is presented as someone that lacks the money to pay the cab fare or to own an audio tape recorder, even though this is essential to his job, as well as having Kiarostami’s crew complaining about their aged and obsolete film technology that serves as an excuse for the film’s later sound capture problems, therefore adding a few more layers to the discourse on the status and resourcefulness of common Iranian people. It is important nevertheless to attentively listen to Sabzian’s defense, as this will provide the justification for his behaviour and when one actually comprehends where he comes from, it’s hard not to sympathize with this sad, lost man.

From the outset he recognizes his guilt and seems genuinely remorseful, his actions are never declared as rightful, though a justification is promptly provided. Still, his personal story is moving and his calm, poised narration comes across as raw and detailed to a very intimate, psychological degree that is impossible not to evoke some empathy. By recounting the events that lead to his criminal actions, which contextualize the condition of many people in the country, an image of Iranian society starts to take shape and is given the spotlight through Kiarostami’s work.

As a country with such rich, ancient, brilliant culture and arts, it feels natural that a kind soul that had been locked in metaphorical solitary confinement, found in art, in this case cinema, the medicine for his ailment, and plunged so deep in it, as a parched man in the desert would dive into an oasis, it created a fantasy so as to shield him from his surroundings. Kiarostami’s “Close-Up” may appear as a quirky and elementary story to some viewers. However, this superficially unassuming outward look hides a substantial amount of interplay, that stimulates the projection of various interpretations, with many theories carrying a glimmer of validity on their own.

Cautious observation allow one to perceive “Close-Up” as a series of lies and facts, jumbled together for an ambiguous reception by the external viewer, since in it we find the film itself as a fiction, but one that was based in the reality that was the tricking of the Ahankhah family. This tricking was based on Sabzian’s fiction while pretending to be director Makhmalbaf, though Makhmalbaf himself exists and is a real Iranian film director, that even appears as himself on the film. This exchange between mutually exclusive dimensions provokes many questions and out of the many that arise, some in particular concern the trickery employed by the characters in this act.

Most people would not hesitate to call Sabzian the clear charlatan in this story, since he managed to fool the family, and even in early stages of the trial, Mehrdad Ahankhah puts up the question on whether Sabzian is putting up an act as well in the courtroom, solely with the goal of obtaining leniency and forgiveness. But the Ahankhah family also seems to be using Sabzian as well, perhaps as a tool to disrupt the boredom of their present lives? At the same time, couldn’t the family be accused of some level of deceit, by following Sabzian’s faux persona after their professed suspicion and by choosing to continue with the deception after learning of his false identity?

Could they be tricking the audience into believing that the way they perform in the film was exactly as it happened? Isn’t the performance itself, regardless of being faithful to the events, a trick on its own? On the other hand, what role does the director play in this charade?

Isn’t he perhaps leading the audience on, by pretending to put out documentary footage that was actually planned and rehearsed, or at least previously discussed? This leads to a broader question, since now we are forced to ask: Do we, as spectators, play an active role on our own deception, since we willingly take ourselves to the theatre to observe a falsified reality? For what purpose?

What does this say about the movie and cinema in general? Kiarostami has something to say about this in an interview where he talks about his career and film style: “This is exactly the opposite to what Hollywood is doing at the moment, which is brainwashing the audiences to such an extent that it strips them of any imagination, decision-making or intellectual capacity, in order to captivate them for two hours. In my films there are always some breaks, such as when a prop assistant brings a bowl of water, and hands it to an actor in the film.

This gives the audience time to breathe a little and stops them from becoming emotionally involved and reminds them that ‘Yes, I’m watching a film’”. Many people, if not most, go to the movies to simply distract themselves and spend a couple of hours. Sabzian too indulged in a voluntary escapade to free himself from his existential bondage, a decision he then regretted, since it caused him more harm than good.

Perhaps Kiarostami is attempting to tell us that cinema, and by extension all art, should be taken more seriously as a proper means for self-actualization, instead of purely relying on it for mere escapism and diversion, that besides its capacity to mesmerize us and take us to other worlds, art can and should be used by ourselves as a vehicle for enlightenment, for attaining a encompassing comprehension of the world, a truth that will benefit the audience and help them return to reality not with the expired sense of having simply shunned the problems away for two hours, but with the insight that allows one to face all the upcoming hours in the future with a different mindset. At its core, “Close-Up” is a classic Kiarostami film, bearing many of the features that define his thoroughly idiosyncratic, apparently uncomplicated style, austere as some have put it before, but which transcends the medium in which these elements are laid, to convey an exhilaratingly moving picture. One will find in it many familiar Kiarostami tropes, such as tightly framed conversations inside moving vehicles and car travelling scenes, or just scenes in which the camera is placed within the vehicle while turned to the external space, like the opening sequence where reporter Farazmand rents a taxi and takes two guards to get Sabzian, or in the re-enactment of Sabzian’s first meeting with a Ahankhah family member on a bus.

One shall witness as well questions and informal conversations with common folk as bystanders, while looking to obtain information or directions, a much typical example of Kiarostami’s inquiry structure seen in various films, and perfect examples of warm quotidian interactions that only a native citizen and speaker could experience. Examples of these are most significantly represented by Farazmand’s quest for the Ahankhah address while being driven in the cab or when Kiarostami himself is questioning the official in the barracks and his soldiers after Sabzian’s arrest. There are also apparently passive moments where silence takes a stand or there is at least a very conspicuous absence of dialogue, and not much else happens.

When talking about such moments defined by inaction, and present in other films of his, Kiarostami said in an interview that “I was constantly looking for scenes in which there was ‘nothing happening’. I wanted to include that nothingness in my film. Some places in a movie should have nothing happening, like in Close-Up, where somebody kicks a can in the street.

But I needed that. I needed that nothing there”. Interestingly, that specific scene has parallels with other events in Kiarostami’s filmographic career, such as the apple in “The Wind will Carry Us”, the zigzag path in “Where is the Friend’s Home?

”, the tire rolling down a highway in “Solution” and in Kiarostami’s first cinematic creation “The Bread and Alley”, where ther e’s literally another can kicking scene. Another aspect of similar nature is present in “Close-Up”, which is having the spectator unconventionally, albeit purposefully removed from what would be the enticing action happening elsewhere, therefore carrying an occluded emotional undercurrent. Examples of such scenes can be traced to when the taxi driver is waiting for Farazmand and the guards to bring back Sabzian, or when Sabzian is waiting for the Abolfazl Ahankhah, the family patriarch, at his living room.

There are also the familiar colloquial dialogues among secondary characters of seemingly unimportant nature, but revealing socio-cultural aspects of Iranian society, such as when the taxi driver engages in small talk with the two guards as they wait for Farazmand to return from the Ahakhah’s home. The presence of a naïve and lying figure as one of the main characters, amid its narrative, can be testified in plenty of Kiarostami’s films, with Hossein Sabzian taking that familiar role in this specific film. One will also find moments in which the people’s humanity shines brightly, exudes powerfully and unpretentiously, without resorting to melodramatic devices or sentimental cues, a prime signature of Kiarostami’s profound simplicity and humanism, and the major examples in “Close-Up” can definitely be pointed at the poignant scenes when Ahankhah’s family have a final opportunity to pardon Sabzian and especially when Sabzian personally meets Makhmalbaf and reencounters Abolfazl Ahankhah back in his home after the trial.

Additionally is the already mentioned substantial and convincing dalliance with reality and fiction, that blurs the lines between both dimensions depicted on screen and result in a cinematic experience that startles and envelops the spectator like few other artists were able to achieve. Taking the audience for a ride and afterwards inform them of his trickery by subtle means, was a major component of Kiarostami’s approach to film, markedly after “Close-Up” in particular. His convincing highly naturalistic, even if artificial reproduction of apparently unscripted moments and scenes, could come across to many as a trait or mannerism of Iranian’s film production scheme but should in fact be taken more as a homage to it, given its carefully planned conception, nevertheless allowing the spectator to gaze at it and find new ways of looking at film.

The finishing touch, and an aspect that is present in every film creation by Kiarostami too, is obviously its careful cinematographic delivery that confers to every frame outside the documentary footage in the courtroom, an entrancing softness and beauty, whether it’s the beguiling close-up portraits of its characters, the mid-shots enclosing the gorgeous backdrops, or the formally rigorous full shots, all displaying a keen eye for composition and sensibility towards the light that tickles the surfaces of the subjects and their space. On a sidenote, it will be interesting to note that although being, as usual, completely absent throughout the film, music finally appears on the magisterial reunion scene, where initially Sabzian and Makhmalbaf first meet and ride the bike, to then meet Ahankhah at the latter’s home, and makes an impact not just because of its restrained but precise temporal use and the beauty of the track itself, but because the track was present in a previous film by Kiarostami called “The Traveller”, thereby connecting Sabzian to the film which himself had praised earlier as one of the inspirations and artworks that have marked him, shaped his soul and brought him to where he is today. Naturally, as the director, Kiarostami was often questioned about “Close-Up” in various interviews and events, so it might be enlightening to learn about how he felt towards it and engaged it from the point of view of the author.

Kiarostami seemed to identify himself with the real people he directed in his film, at one point saying that “in Close-Up I find myself in the character of Sabzian and in the Ahankhah family who are deceived. I’m like the character who lies, and at the same time, I’m similar to the family who’s been lied to”. No doubt “Close-Up” has a personal flair to it, seen from Kiarostami’s perspective, not just due to relating to its subjects, but the film probably held a special place in the director’s heart too, considering the reputation it has brought to him and especially the fact that it represented a refinement of his abilities that enforced the shaping of a style he would come to employ consistently afterwards.

He is quoted as saying that “it was a film that made itself, which came about completely naturally. I shot the film during the day and made notes at night. There wasn’t much time to think, and when it was finished, I watched the film like any other spectator, because it was new even to me.

I think it’s something completely different from what I’ve done”. So, what does Kiarostami then think about his product, in terms of structure and nature, given its opaque offering and resistance to definitive labelling? “I personally can’t define the difference between a documentary and a narrative film.

For instance, Close-Up, a movie that’s based on a true story, with the real characters in the real locations, would seem to qualify as a documentary. But because it restages everything, it isn’t a documentary, so I don’t know which drawer to put it in. You know, even a photograph can tell a story, and the very fact that you’ve picked one scene and omitted other scenes, or selected one lens over another lens, shows that that you’ve done something special and told a story with that photograph: you’re intervening with reality”.

What runs underneath this intelligent remark on the recreation of reality and the active role of the one recording it in a certain configuration, goes straight to the reasoning behind the picking of the lens that gives the title to the film, and is the core of Kiarostami’s cinematic purpose, to interact with his audience not as passive consumers but as autonomous producers of meaning, capable of recognizing and asserting the essence of what is displayed. It is unfortunate however, that Kiarostami’s purpose through “Close-Up” and his other filmography, wasn’t always understood or tolerated, despite his good will and humble intent. Though having said that “Close-Up gives people the chance to know that Sabzian is basically a nice person who has enormous social difficulties”, in itself a statement that is rooted on a compassionate and comprehensive understanding of humanity, Kiarostami was not safe from criticism and some people even accused him of “ignoring the dignity of humanity” and of “killing humanity spiritually”, a baffling accusation that is as absurd as classifying Gandhi as jingoistic or the Dalai Lama as a warmonger.

Despite being one of the most successful of Kiarostami’s films at the Iranian box office, the critical reception of the film was dispiriting, almost universally negative, with critics bashing the film’s peculiar structure, looking at it in politically-tainted glasses, or just dismissing it as a publicity stunt for Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf. Luckily, it acquired a cult status after an exceedingly warm welcome abroad and particularly in France, while earning awards in festivals in Italy, Canada and Turkey, which resulted in a positive re-evaluation back home, and being nowadays considered one of the greatest films of the century by the general professional critique. As the film’s spectators, perhaps there’s one last question to ask: Despite the fake promise made by Sabzian to the Ahankhah family, that he would be shooting a film at their abode, in the end did he not actually do it?

He managed to get Abbas Kiarostami, one of the greatest of all Iranian filmmakers, to shoot a film with him, pretending to be Makhmalbaf, at the Ahankhah’s home, a fact made out of a fantasy, an empty promise made real, a fiction that became reality, by the power of soul and art. Therein lies much of the incredible power of “Close-Up” and the grounding for its timeless status, a work that is bound to inspire all film viewers of any place and time. If you enjoyed this video essay, feel free to like, comment, share or subscribe to the channel, and check other videos if you’re interested in cinema from the world.

Thank you for listening and see you next time.

Related Videos

39:36

Kiarostami and Sabzian کیارستمی و سبزیان

Farid Bozorgmehr

57,718 views

18:21

You Don't Know What Crime Is (Bicycle Thie...

1C2

7,538 views

1:58:27

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI In Conversation With... |...

TIFF Originals

170,250 views

45:00

The Matrix Was a Documentary

Optic Lure

2,073,360 views

27:23

How THIS Scene Became a Modern Masterpiece

Lancelloti

5,239,424 views

24:57

The Madness of Werner Herzog

Pirate mp3

199,794 views

13:30

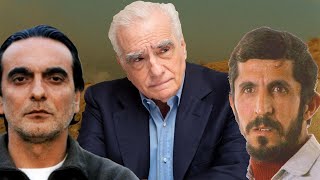

Abbas Kiarostami honored by Martin Scorses...

Peter Scarlet

59,747 views

22:49

Why 2001 Was the Hardest Film Kubrick Ever...

Just One More Thing

319,765 views

19:59

Abbas Kiarostami: The Moment of Truth

Bucket List Reviews

32,524 views

16:12

Mel Gibson Exposed Hollywood and Paid the ...

The Creators

906,884 views

20:14

Abbas Kiarostami Best Movies - Analysis

Life Goes On In Iran

3,334 views

31:29

A Walk with Kiarostami

lachambreverte

39,069 views

1:50:30

അമ്മ അറിയാൻ AMMA ARIYAN_RestoredFullHD1080...

Potato Eaters Collective

124,977 views

48:41

abbas kiarostami interview

Abbas Hojatpanah

36,534 views

10:53

Video Essay: What Abbas Kiarostami Taught ...

No Film School

21,593 views

8:38

Final Draft: Abbas Kiarostami on Film

IUCinema

67,192 views

15:49

You Don’t Understand How Landmines Work (a...

World War Wisdom

985,934 views

22:06

The Story Behind Iranian Heart-Touching St...

Unique Storytellers

2,074 views

10:50

when film critics clearly just do not get ...

CinemaStix

1,159,938 views

5:00

Martin Scorsese on Abbas Kiarostami

James Whale Bake Sale

32,399 views