Brazil's Psychedelic Samba Pissed EVERYBODY Off

84.06k views4275 WordsCopy TextShare

Bandsplaining

Follow-up podcast on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/bandsplaining

Violence, polarization, campus ...

Video Transcript:

At a university auditorium, a 26-year old performer walks out on stage. With long curly hair, plastic clothing and necklaces made of electrical wiring and animal teeth, his mere presence evokes a visceral reaction. Amid a chorus of boos and screams of profanities, calling him an “imperialist,” the band begins their noisy set.

This only makes the audience angrier, as they soon begin hurling trash. One particularly sharp projectile draws blood. And no, this did not happen at UC Berkeley circa 2017.

This was Brazil in 1968, when the country was in the grips of an increasingly-ruthless military dictatorship that came down particularly hard on left-wing students. But here’s where it gets a bit tricky. The performer, whose name was Caetano Veloso and his friend Gilberto Gil, were no supporters of the dictatorship either.

Just a few months after this incident, their stage performance would get them in even deeper trouble with the government. They were arrested, imprisoned, and later exiled from the country. So what was it that made Veloso and Gil so utterly despised by the left, and yet also, so dreaded by the right?

Their crime… was Tropicalia. Tropicalia may have taken place a long time ago, in a setting that, for many of us, feels far away. But it’s a story that’s also eerily timeless, as history repeats itself, or perhaps simply continues to echo today.

In a few key ways, the history of the United States and Brazil are quite similar. Both lands were discovered by European settlers, who dominated the indigenous inhabitants and then brought over large numbers of enslaved Africans. Both countries have turbulent histories of racism and discrimination, and yet, in an ironic twist, it was the descendants of slaves who were instrumental in developing each country’s musical heritage.

In America it was blues, jazz and rock – you know the story. But in Brazil, it was Samba. The rhythm of samba is rooted in the music of traditional religious ceremonies practiced by African Brazilians.

By the late 19th century it was mixing with the music and dances of European origin. While initially the sound of the Black urban favelas, with lyrics about malandros; bandits on the run from the law, samba would soon be promoted by Brazilian President Getulio Vargas, in an attempt to unify the country. In another ironic twist, Vargas, who was briefly friendly with the fascist leaders of Europe, had once broadcast a block of samba music directly to Nazi Germany.

“I always think about Nazi Germany listening to that very black, very African-Brazilian music. ” Just a funny side-note In the 1930s, mainstream Samba acts would emerge that were widely popular across social classes, such as Dorival Caymmi or Carmen Miranda the latter of whom you might recognize as The Chiquita Banana Girl. When Miranda left for Hollywood in 1939, she was beloved in her home country.

But her roles as the exotic, fruit-laden love interest were criticized back home. Many felt that she was propagating stereotypes that caricatured Brazilian culture. In Carmen Miranda there represents a paradox of Brazilian music.

Samba would never have been possible without the fusion of Afro-Brazilian and European sounds. Later, it was an injection of American bebop that gave Bossa Nova its intoxicating, cool drive. But none of these evolutions happened peacefully.

Brazilian nationalists have long lamented the foreign influences that watered down their culture, or turned their musical exports into the butt of a joke. And by the time rock and roll emerged, this tension was stronger than ever. So there’s a common misconception about rock music that’s not exactly obvious if you’re from the US.

Here, we tend to associate 60s rock with left-wing politics. After all, this was the music of Woodstock, the Vietnam war protests, and so on. Except for that one moment where Bob Dylan got booed on stage, the only people who “opposed” rock were stodgy religious conservatives.

Well, the same was not true elsewhere in the world. As the US emerged a superpower, those who viewed American force with suspicion, also saw American culture with suspicion. This was especially true in Brazil.

In the late 50s, an alliance with the United States brought an economic boom. Many in the middle class were buying their first cars, TVs and refrigerators. However, Brazil still had immense inequality, and many on the political left felt that modernization was coming at the expense of the working poor.

Brazil briefly had a left-wing president in João Goulart who attempted to enact labor reforms, but his tenure was marred by frequent labor strikes and economic decline. Fearing a communist revolution in the vein of Cuba, Brazil’s conservative leaders panicked. In 1964, they staged a coup with the backing of the United States, replacing Brazil’s democracy with a pro-western military dictatorship.

The communist party was banned, opposition was arrested, even executed, and censorship crept in. What emerged was a bitterly polarized society, where music became key to one’s political identity. Students, artists and intellectuals who formed the coalition on the left embraced a kind of protest music that fused Bossa nova with Brazilian folk and politically charged lyrics.

Artists like Chico Buarque, Tom Jobim, and Elis Regina became synonymous with the movement known as MPB or Brazilian Popular Music. They played strictly acoustic music, but hidden within their cool demeanor and complex chords were scathing critiques of the dictatorship. MPB reached the masses through TV shows like O Fina Da Bossa, but it wasn’t the only genre competing for the attention of the youth.

Jovem Guarda was a TV show that featured bands strongly influenced by the British invasion and American rock n roll. Hosted by Roberto Carlos, the singer became the most popular Brazilian rockstar. As music historian Christopher Dunn explained, “Jovem Guarda songs tended to avoid political and social criticism,” instead opting for “themes of male bravado, sexual liberation, fashionable clothes, fancy cars, and wild parties.

” Now, despite the fact that “Jovem Guarda” and “O Fina Da Bossa” were broadcast on the same channel, they might as well have existed in two different worlds. They represented drastically different ideologies about the state of Brazil, and the battle over its national identity. To fans of MPB, Jovem Guarda trivialized everything they stood for.

Instead of awakening the masses with a message of political urgency, it pacified them with odes to consumerism. Instead of glorifying Brazil’s musical heritage, it surrendered to American imperialism in the form of 4/4 rock beats. And to Jovem Guarda fans.

Well… they just didn't see what the big deal was in picking up an electric guitar. MPBs distrust of Jovem Guarda reached a fever pitch, where artists were subjected to purity tests. Those who incorporated any elements of American popular music would face heavy criticism, such as Jorge Ben Jor who flirted with R&B.

After appearing on the Jovem Guarda TV show in 1966, he was blacklisted from the MPB community. The mere appearance of electric instruments could bring MPB audiences into a fury, booing and taunting the performers. In 1967, a rally was held in Sao Paulo that became known as the “March Against The Electric Guitar.

” Initially planned as a marketing stunt to promote a new MPB TV show, protesters marched in the street under the slogan “Defend What is Ours” Granted, not all MPB performers were pleased with this direction. Nara Leão and Caetano Veloso were disturbed as they watched the scene unfold from their hotel. She had turned to him and said, this looks like facism.

So we’re back to this character. The guy with the crazy outfit on stage. Caetano Veloso was on the MPB side of things.

But for him, it wasn’t so much about politics as it was his love of Bossa Nova. Veloso grew up in a small town in Bahia, a state in northeastern Brazil. As a kid, he listened to music of all kinds From sambas to tangos, Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole But this wasn't how he received his musical awakening.

That came from João Gilberto. Largely regarded as the first Bossa Nova album, Veloso describes in his memoir the thrill of hearing “Desafinado” or “out of tune,” for the first time. It was a “deeply penetrating and highly personal interpretation of the spirit of samba.

He did this through a mechanically simple but musically challenging guitar beat that suggested an infinite variety of subtle ways to make the vocal phrasing swing…” Bossa Nova would inspire Veloso towards a career in music, soon relocating to Rio De Janeiro, and befriending MPB stars. For a time, it was exciting. But while Veloso was absorbing the cutting-edge music from around the world, from Stockhausen to The Beatles, his peers were bickering about how to make their music as authentically Brazilian as possible.

“They were, as we were, sons of Bossa nova. So they wanted refined harmonies, complicated harmonies, left-wing-ish lyrics, and a little flavor of regional music from different areas of Brazil Mostly the Northeast And we thought that was passive, you know, defensive. ” He didn’t see how they could counter the oppression and censorship of the dictatorship with their own brand of censorship.

“We were aware that we were living in a period of extreme violence… We did not want to represent the tradition of a small elite that wanted to remain small. We wanted to break with that and bring a form of artistic expression to popular music that contained violence: attitude, poetry and sound. ” And Veloso would soon find two important allies in composer Rogerio Duprat, and fellow singer/songwriter Gilberto Gil.

By the way, I also want to just acknowledge that, by coincidence, Gilberto Gil’s first name is the same as João Gilberto’s last name, but, no relation. Gil is also from Bahia, though his career had moved a bit faster than Veloso’s and he was traveling frequently between cities for performances. It was during a visit to the Northeastern state of Pernambuco where he had a vision: Listening to the music of regional group Banda de Pífanos, alongside the recently released Sgt.

Pepper. For Gil, Veloso, and Duprat, the message was becoming clear. To create something groundbreaking, they could no longer shy away from the global pop vanguard: the electric guitar, psychedelic string arrangements, or pop harmonies.

They could no longer fear commercialization or mass communication. To be truly revolutionary and to illuminate Brazil for what it really is, all source material had to be on the table. So in other words, they started to plan a mutiny.

In the late 60s, televised song competitions were enormously popular in Brazil, and one of the key ways that new music would break out. Naturally, it was the perfect place to launch their insurrection. In just the first few seconds of “Domingo No Parque” you can hear the psychedelic vision of Gil start to take hold.

A chaotic march a la Sgt. Pepper that begins to break down. The song then cleverly transitions to a baião rhythm, held down by a berimbau: The single-stringed instrument that produces deep, rhythmic tones.

Now, hearing it live for the first time, it’s difficult to convey how shocking this was. Joined by Os Mutantes on stage, the combination of Afro-brazilian music with psychedelic pop was unlike anything they had heard before. Veloso had a groundbreaking performance as well.

But I want to focus on a different composition of his. One that would be so pivotal, it would give this movement its name: Tropicália. On the surface, “Tropicália” was an ode to Brasilia; the ultra-modern capital which had just been completed.

But a bitter and sarcastic one. An anthem to the myriad contradictions of an industrial tropical nation. The avant-garde arrangement by Julio Medaglia begins with the chaotic squeals of an untamed jungle.

A voice recites the letter written to the King of Portugal upon the discovery of Brazil. “Everything one plants in it, everything grows and flourishes. ” The lyrics are full of cliches, symbols and imagery that Veloso hoped “would somehow reveal the tragicomedy that is Brazil.

” With all the fanfare of a superhero theme song, he equates Bossa Nova the pride of the intellectual class, with palhoça, a primitive grass dwelling. As the narrator enters the city of Brasilia there is the image of a dead child, sticking out his hand to a swimming pool. He calls the city a monument made of paper mache and silver a facade of modernity hiding the deep inequality within.

But the most controversial lines come at the very end. For the final stanza, Veloso places “A Banda” a hit protest song by Chico Buarque next to Carmen Miranda, and all while giving a nod to the Dada movement To the left wing, this was a vulgar betrayal. Carmen Miranda was a symbol of American imperialism The stereotype of a “sexually exposed Brazil, hypercolorful and fruit-full” submissively falling into the arms of Hollywood lovers.

But for Veloso, there was nothing to be insecure about. Just as Andy Warhol could find the mundane beauty in a Campbell’s soup can Veloso was embracing the Brazilian-ness of tropical kitsch. The playful approach to consumerism was present in other tracks too like “Superbacana” or "Supergroovy" As Christopher Dunn writes, this imaginary superhero is pitted in a battle against Uncle Scrooge and a battalion of cowboys as a metaphor for American imperialism.

And yet, the song itself can’t escape being a jingle for various household products. Now, instrumentally, this wasn’t the most avant-garde music the tropicalists would write, But there are two tracks that I find particularly fun. There’s "Eles" with its swirling backwards organ.

And then there’s ‘Annunciation’ a baião-like rhythm that alters hypnotically between two chords. And all while telling the biblical story of Gabriel informing Mary she would be carrying God’s child. There's even a line where the angel asks Mary not to go on birth control.

Upon it's release, Veloso’s album hit like a storm. I mean, it put everyone on the chopping block: From the pro-military conservatives to the populist left. He and Gil became media sensations, but they were panned by fellow musicians and the musical press.

The harshest response came from students. Tropicalia was challenging their political orthodoxy, and their reaction was to shout it down. The documentary “Tropicalia” describes once such instance when the pair was invited to attend a debate It was a foreboding sign of what was to come.

Just as 1968 was defined by chaos around the globe, the year would be extremely eventful for Brazil. In March, during a protest against high food prices two students were shot and killed by military police. This led to a surge in protests, culminating in the “March of One Hundred Thousand” in Rio de Janeiro which Veloso, Gil and Chico Buarque, among many other artists, attended.

While the march was peaceful, the military responded with even harsher censorship and a clampdown on public demonstrations. Right-wing vigilante groups became more active, such as the CCC or Command For Hunting Communists. If you recall this song by Chico Buarque we played earlier it was written for a play of the same name.

During one staging in São Paulo, the CCC invaded the theater, destroying the set and beating up the actors. So with the fabric of society unraveling around them, how did Veloso and Gil respond? Well, they doubled down absorbing the energy, violence and contradictions and releasing an album that would be Tropcalia’s magnum opus.

This time, with a little help from their friends. Imitating an upper-class family portrait, we see performers Gal Costa, Nara Leão, Tom Zé, Os Mutantes, Veloso, and Gil, composer Rogério Duprat, and poets Torquato Neto and Capinan, represented by his graduation photo. The album varies wildly in style; the title track, performed by Os Mutantes, sounds more like the psychedelic pop of Pet Sounds than anything produced in Brazil prior.

It's title, which translates to “Bread and Circuses,” is a reference to the ancient Roman idiom about how politicians nullify the masses with servings of food and entertainment. The lyrics present an upper-class family who are too busy hanging out in the dining room to be moved by revolutionary art. Political context aside, it’s a song that, to me, cuts deep.

It really lays out that painful futility of songwriting when you have an idea that is making tidal waves in your head, but everyone is just too busy being born or dying to… understand. The song “Batmacumba” is a masterclass of lyrical minimalism. The title is a portmanteau of Batman and Macumba a term for the traditional Afro-Brazilian religions that gave birth to Samba.

The first line adds “iê iê” to the end A reference to the chorus of the Beatles song “She Loves You" while the second line adds Obá, a deity in the traditional religion. And with only these 2 repeating words, Veloso and Gil make an incredibly powerful and controversial statement: That the products of the global culture industry like Batman and rock can sit equally alongside Macumba as a part of Brazilian identity. Now there’s 2 more interesting things about this song.

For one, Os Mutantes released a version of their own and it features this absolutely brutal lead guitar with a sinister tremolo. Secondly, as the song progresses, syllables are gradually removed. Then later, added back in.

So when you zoom out and see the whole lyric sheet, it resembles the wings of a bat. You gotta hand it to them. “Parque Industrial” by Tom Zé is a satirical anthem to Brazil’s booming industrial output, with lyrics about all the new products for sale.

Tom Zé also put out a solo album in ‘68 which, based on the comments I got on this community post, is clearly a fan favorite. It’s a really fun and irreverent album that pokes fun at Brazil's commercial urban life. I particularly enjoy the irony in “Quero Sambar Meu Bem” or, "I want to samba my dear" a song that lacks any samba beat whatsoever.

And I should add that many other tropicalists were releasing solo albums, like Gilberto Gil, who continued the genre-bending of Domingo no Parque. As well as Jorge Ben Jor, the singer we mentioned earlier who was blacklisted for being too R&B. He found a new home in the Tropicalia gang, and although this album came out one year later, we’re going to sneak it in.

But, going back to the collaboration album, no discussion of Tropicalia would complete without mentioning “Baby,” arguably the most famous tropicália song of all. Written by Veloso and sang by Gal Costa, it feels like a love song, at least on the surface. But the narrator speaks in the form of a hard-line advertisement, telling you about all the products you need.

You need to eat an ice cream, you need to learn English, you need to listen to Chico Buarque and Roberto Carlos These guys just can’t stop picking on Chico Buarque. At the peak of the song the narrator stops and says “I don’t know… just read my t-shirt” Baby, baby I love you No doubt for many listeners it is simply a beautiful and romantic song, but I can’t help but feel a twinge of dread hearing it. It’s as though, for the narrator, love can only be mediated through the exchange of products.

It hits a little too close to home… As Veloso described in his book, the day he and Gal finished recording “Baby,” they went out to a restaurant to celebrate. There, they ran into Geraldo Vandré, the MPB singer, who asked to hear a sample. But as Gal began singing Vandre interrupted her suddenly, exclaiming “that’s a piece of shit!

” As Veloso recalls, “he tried to argue, saying that we were betraying the national culture… He alleged that what Brazil needed was what he, Vandré, was doing namely, songs to 'enlighten' the masses and that since the market could not bear more than one strong name at a time, for the general good of the country and the people we should put all our eggs in his basket. ” Of course, the Tropicalists were used to such criticism. But the ferocity of Vandre’s response was perhaps a warning sign.

It’s September, 1968, and we’re back at that auditorium at the Catholic University in Rio De Janeiro. It’s a qualifying round for the 3rd international song competition, and millions of people are watching at home. Inside the auditorium, a tense audience is waiting for Veloso’s name to be called.

The moment he walks out on the stage, backed up by Os Mutantes, they are inundated with jeers and boos. “I knew I was being provocative,” Veloso wrote. “But the hatred that was stamped on the faces of the spectators was fiercer than I could have imagined.

” Veloso had prepared a song just for the occasion: It’s Forbidden to Forbid, his deepest venture into hard rock yet. But instead of reciting the prepared lyrics, Veloso went off-script, directly confronting the students: He continues, “you are the same youth who will always, always, kill tomorrow the old enemy who died yesterday. " With the screams of the audience only growing, Veloso continued his diatribe for over four minutes He tells the audience they are just as bad as the right wing militias who beat up the cast of Chico Buarque’s play earlier that summer.

With Gilberto walking out onto the stage to join him, and with trash and debris reigning down upon them, Veloso announces to the jury that he wishes to be disqualified. "Gilberto Gil is here with me to put an end to the festival and the imbecility that reigns in Brazil. " In the months that followed, Tropicalia would reach its greatest heights.

Veloso and the gang scored a primetime TV slot, where they combined wild performances with provocative set designs; the bands performing inside a series of cages, which were ripped apart at the end of the episode. A reenactment of the Last Supper, but on the table was only bananas. With the holidays around the corner, Veloso performed a Christmas song while holding a revolver against his head.

The footage of their TV show, called “Divino Maravilhoso,” would no doubt be considered a national relic today. But sadly, none of it exists. The tapes have apparently been destroyed, and it remains lost media.

On December 27th, 1968, in the wee hours of the morning, Veloso and Gil were arrested in their apartments by the military police. They were brought to Rio De Janeiro and placed separately in solitary confinement. A week passed, and neither were told what they were arrested for.

Eventually they were transferred to another holding cell, this time shared with fellow political prisoners. Although they were told inmates of their status would not be subject to any violence, at night they could hear beatings take place down the hall. At one point Veloso was brought outside at gunpoint.

He was told to walk down a path until it reached a wall, then ordered to stop and not look back. Veloso was certain he was about to be executed. But in an apparent cruel prank, the guard revealed Veloso was merely getting a haircut.

It was only after a month and yet another prison transfer that Veloso finally found out what he was arrested for. During a show that fall, a banner by artist Helio Oiticica was put on display, featuring the bullet-ridden body of criminal Manoel Moreira. The text read, “be an outcast, be a hero.

” This apparently led to an inquiry into Veloso and Gil, and their subsequent TV appearances didn’t ease any tensions. When the authorities saw their wild and confrontational performances, they saw anarchy. And this scared them more than protestors.

Finally, after 2 months locked up, Veloso and Gil were flown back to their home state and placed on house arrest. There they remained another 4 months, unable to work or perform publicly, although they did use the time to record new albums, which saw their psychedelic experiments taken even further. Veloso’s “Irene” was written in prison about his sister, who’s image would appear in his cell.

It’s just a beautiful, heartbreaking song with incredible production from Duprat. Finally, Veloso and Gil were given the “opportunity” to leave the country. To raise money for their exile, they were permitted to play one final show, provided they did not use it to incite the crowd.

This farewell concert was a bittersweet affair. Though it wasn’t allowed to be professionally recorded, a secret bootleg was later released as an LP. Tropicalia was officially over.

Veloso and Gil would make their way to London, while back home, Brazil would enter it's "years of lead," a period marked by severe cultural repression and political violence. Many other prominent musicians were arrested, or left the country due to an official or self-imposed exile, including Chico Buarque, Geraldo Vandré and Nara Leão. However, Tropicalia had undoubtedly left its mark on Brazilian music.

The genie was out of the bottle, the wall between MPB and Jovem Guarda was obliterated, and in spite of the strict censorship, the 70s would end up a highly creative time for Brazilian music If you have a favorite song or album from the post-Tropicalia era, or just song you think we should have included, please drop a comment below. While you're down there, give us a like, give us a subscribe, and check out the link to our follow-up podcast on Patreon which is going to pick up right where we left off and continue the tropicália story to the present day. Alright guys, until next time.

Related Videos

29:10

The Meltdown of Russia's Music Scene

Bandsplaining

238,810 views

23:57

Do They Know It's Genocide? The Band Aid Tale

Bandsplaining

184,034 views

18:04

The 2005 Radio Scandal Was a Glorious Mess

Bandsplaining

457,767 views

22:16

BRAZIL'S REAL-LIFE GOTHAM CITY? (São Paulo)

Dots on a Map

379,124 views

21:13

Peru’s Response To 60s Rock? Psychedelic C...

Bandsplaining

415,232 views

19:51

How we KILLED the Greatest Kind of Vehicle

Bart's Car Stories

480,055 views

21:12

The Ahhiyawa Problem

Dig.

131,963 views

24:02

How An Obscure 70s Genre Has DEFINED Moder...

Bandsplaining

262,180 views

32:25

The Beatles Recording of Revolver

Film Retrospective

263,953 views

25:05

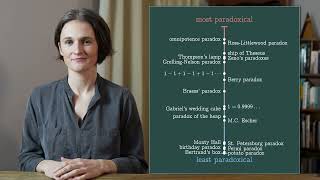

Ranking Paradoxes, From Least to Most Para...

Chalk Talk

233,094 views

34:06

How Bands Pay Bribes To Get Stuck In Your ...

Bandsplaining

100,847 views

22:15

How West Africa Went Psychedelic

Bandsplaining

185,286 views

20:56

The Unlikely Electro Trio Who Made an ABSO...

Bandsplaining

18,249 views

4:27:03

The Sgt. Pepper Sessions | Beatles Documen...

Beatles Bible

320,777 views

15:47

Music Facts To Share At The Dinner Table

Bandsplaining

162,629 views

46:03

China’s Punk Rock Talent Show: A National ...

Bandsplaining

15,969 views

1:41:11

Yoko and The Beatles

Lindsay Ellis

2,343,000 views

14:11

Why are there 12 different notes?

Montechait

124,647 views

2:06:25

The Best Of 1985 Part 1

Beppe Martire

856,499 views

1:06:29

What New Music Genres Were Created in the ...

Bandsplaining

51,406 views