Every Options Strategy (and how to manage them) | Iron Condors, Vertical Spreads, Strangles

52.3k vues9129 MotsCopier le textePartager

tastylive

Subscribe to our Second Channel: @tastylivetrending

Check out more options and trading videos at www...

Transcription vidéo:

If you're not ready to manage your trades, then you're trading wrong. In the options world, there are eight strategies that most traders use, and the successful traders stand ready to make the necessary adjustments with those strategies when they need to be made. It doesn't take more than a couple of minutes to follow these mechanics, and I promise it will make all the difference in your trading. So welcome to our Options Crash Course Strategy Series! I'm Jim Schultz, and I'm going to be your tour guide for this series. First up on the docket, we are

going to cover the short vertical spread. What we want to do is hit three things: we're going to discuss managing winners, managing losers, and managing the dance floor. But before we get to all that, let's remind ourselves what a short vertical spread is. A short vertical spread is a defined-risk directional trade, and this is a great option for a beginner trader who's looking to understand the mechanics and get their feet wet in the world of options trading. It's a very strong trade with a ton of peace of mind to know what your worst-case scenario is

on order entry. But how do we set these guys up? Well, they all set up basically the same: you sell one out-of-the-money option and then buy a second further out-of-the-money option. By buying that second option, that is the thing that puts the safety net in place. As a reference point, we typically like to collect around one-third the width of the strikes. So if it's a $2 wide vertical spread, we'd collect about 67 or 70 cents. If it's a $3 wide vertical spread, we'd collect around a dollar. We feel that this provides a great risk-reward balance

that sets us up in a nice high-probability situation. Okay, easy enough. But once you put this thing on, how do you manage it? First up, managing those winners—right? The easy stuff, the fun stuff. You put on a short put spread and the stock goes higher. That thing's going to manage itself; it's not going to be difficult to handle because it's going to be an easy winner. It's going to be a fun time. You put on a short call spread and the stock goes lower— that is also going to be a fun time; it's also going

to be an easy trade. You set your profit targets at 50% of max profit for either the short put spread or the short call spread, and if the stock accommodates you, man, you just take it off, move on, and find another opportunity. Don’t overthink it. Okay, so now for the not-so-fun stuff: how do you manage your losers? What do you do when the position is a loser and the stock isn't accommodating you? Thankfully, though, this situation is actually pretty simple too. If you get to 21 days to go, then look to roll this thing out

to the next monthly cycle. Don't change the strikes and don't add units; just pick this guy up, move it out to the next cycle, and drop it down at 21 days to go. However, what you want to make sure of is that you can roll forward for a credit. You don't want to pay a debit to roll your position because this would add risk to the trade. So, if you can roll forward for a credit at 21 days to go, then by all means, do so. But if you have to pay a debit—which will be

the case if the position is too far gone—then you have to sit and wait. We control our size on order entry, so in the event that this does happen, it's something we are ready and willing to absorb. To be perfectly honest, this is going to happen to you a time or two, or ten, or twenty over your trading career. It's a probabilistic certainty. But remember, as high-probability traders, this is not going to be the most likely outcome; we are most likely going to be managing our winners. Alright, so now we know how to manage winners

with short vertical spreads, and we know how to manage losers with short vertical spreads, but what do we do with everything in between? Right? What do we do with all those dance floor situations, where we're at 21 days to go, and maybe we have a scratch, a small winner, or a small loser? How do I know how to handle that situation? Well, I'm not even going to pretend that this is going to be an exhaustive list for how to handle those situations, but here is a really good sound strategic way to approach them: look at

the IVR on the trade. Look at the implied volatility rank. If the IVR is still elevated—if the IVR is still high like it was when you put the trade on—then consider keeping it on. Because you know the implied volatility is a mean-reverting entity, and if it does indeed mean revert and come back down, then that's going to help you reach your profit target. If, on the other hand, the IVR has collapsed, then it might be time to take that trade off. Whether it's a small winner, a small loser, or a scratch, it might be the

best move to just close the trade, move on, and find something else. So there you have it, man. That is... How to manage a short vertical spread. Be sure to save this video for reference, and when you are ready, check out the next video inside of this crash course strategy series: long vertical spreads. We are going to cover the long vertical spread, and we're going to follow the same framework that we followed for the short vertical spread. We're going to talk about managing winners, we're going to talk about managing losers, and we're also going to

talk about managing that dance floor—all that stuff kind of in between. So first, let's begin with how a long vertical spread sets up. All right, a long vertical spread is going to set up pretty similarly to a short vertical spread, where you're going to have a long option and you're going to have a short option, but their exact placement is going to be a little bit different. Remember, with a short vertical spread, we focus primarily on out of the money options. Well, with a long vertical spread, we're actually going to be closer to at the

money with our strikes. We're going to go a little bit in the money with our long strike and a little bit out of the money with our short strike, basically straddling the current stock price. With this strategy, we like to be around the at the money strike for the following reasons: we don't want to move too far out of the money because that's going to be a low probability trade. Even though we're buying premium, we still want to be aware of the probability on this trade. We also don't want to move too far in the

money because that will not be a great risk-return tradeoff for this type of strategy. All right, so that's how a long vertical spread sets up. Now, the fun stuff! Let's talk about managing those winners. Right, you have a long put spread on, and the stock goes down—that's going to work out pretty well. You have a long call spread on, and the stock goes up—that's also going to work out pretty well. You set your profit target at 50% of max profit; when it gets there, you take it off, you move on, and you find another opportunity.

All right, easy enough! Those winners, they're going to pretty much take care of themselves. But what about the not-so-fun stuff—the losers? Right, what do you do when this trade moves against you? What do you do when the stock doesn't cooperate? Well, to put it very simply: nothing. You sit and you wait. Sure, if you can roll out at 21 days to go and you can do so for a credit, then you should do that. But if you can't, if the strategy is too far gone and the stock has just not come back to you, you

have to sit and wait. Remember, we control our position sizing on order entry, so if it takes the whole cycle for this thing to come back, then it takes the whole cycle for this thing to come back. If it never comes back, then it never comes back. With our defined risk positions, especially something like a long vertical spread, if the stock doesn't cooperate, then you just have to do nothing. All right, so that is it. That is how you manage a long vertical spread. Again, be sure to save this video for future reference, and then

when you are ready, I will see you in the next video, where we are going to talk about iron condors. In this video, we are going to cover the iron condor, and we are going to follow the same framework, the same protocol, as we've already done. We're going to talk about managing winners, we're going to talk about managing losers, and then we are going to talk about managing everything in between. So let's begin with how to set up an iron condor. All right, so an iron condor is a neutral strategy that benefits most from a

stock that doesn't move too much. It is built from two out of the money short vertical spreads: you have a short put spread below the current stock price, and you have a short call spread above the current stock price. Your best case scenario is both of those spreads stay out of the money; both of those spreads are moving towards expiration where they won't be worth anything. Now, on entry, we like to collect about one and a half the width of the strikes. The short put spread and the short call spread have the same width, so

it doesn't matter which one you choose. But similar to a short put spread or a short call spread, we're looking to collect about one-third the width of the strikes. Now, with an iron condor, it's unique because you have two spreads, so you don't need to collect one-third of the width of the strikes from one spread; you need to collect one-third the width of the strikes from both spreads. All right, so that's how an iron condor sets up. But now, the fun part: how do you manage those winners? It's actually going to be very similar to

what we saw with our short vertical spreads, whether it be a short put spread or a short call spread. We're going to target 50% of max profit. What that means is if you sell an iron condor for a dollar, you're looking to buy it back for 50 cents. If you sell an iron condor for $1.80, you're looking to buy it back for 90 cents. It really is that simple: take these guys off once they reach 50% of max profit, and don't look back. All right, easy enough! What about the not-so-fun part? What about these losers

when the stock moves up significantly or the stock moves... Down significantly well, what you're going to want to do is largely going to be driven by the width of the iron Condor. So let's start with the more narrow guys—your $3 wide iron Condors, your $5 wide iron Condors. You can treat these very much like you treat every other defined risk strategy. You can pretty much just sit and wait; you control your risk on order entry, and then at 21 days to go, if you can roll for a credit, then you do so. If you have

to pay a debit, then you sit tight and do nothing. This is absolutely a viable alternative with these narrow iron Condors. Now to be fair, you could also roll the untested side. So if the stock moves up a lot, you could roll the put spread up; if the stock moves down a lot, you could roll the call spread down. That is going to bring in a credit, and it will reduce your risk, but you have to be aware it's also going to shrink that region of profitability. It's going to make it more difficult to be

profitable on this trade because there's simply less distance between the two short strikes now, and there's already a tremendous amount of friction between the short options and the long options. All right, so that's how you handle the narrow iron Condors. But what if you have a wider iron Condor? What if you have an iron Condor that's, you know, I don't know, $10 or $15 or $20 wide? Well, this is actually going to behave a lot more like a short strangle, which we're going to see in a future video inside this series. Even though the risk

is very much defined because you have so much distance between the short option and the long option, these guys are going to behave a lot more like a strangle. So, it's probably prudent to roll that untested side when one of your sides gets tested, because you have so much additional distance between the shorts and the longs. There isn't going to be as much friction as you would have with a more narrow iron Condor. So what this means is you will be able to reduce your risk, you will be able to bring in more credit, and

you won't shrink your chances of being profitable on the position like you might with a $3 wide or a $5 wide iron Condor. Okay, so that's how to handle the winning iron Condors; that's how to handle the losing iron Condors. But what about all the iron Condors that are kind of like "eh," not really a winner, not really a loser? You get to 21 days to go, and they're pretty much a scratch. Well, this is going to be largely up to your discretion as a trader, but here is a good reference point to use—the same

one that we used with our short vertical spreads. Look at IVR; look at the implied volatility rank. If it's still elevated like it was when you put the trade on, then consider keeping it on. But if it has collapsed, if it has come in a little bit, then you might want to consider taking it off. Following IVR and using it as your reference point here really allows you to take advantage of any volatility mean reversion that might indeed take hold. All right, guys, that is it for the iron Condor. Save this video for future reference,

and hey, share it with a friend, right? Share it with one of your trader friends that's trying to learn about iron Condors. When you are ready, I will see you guys in the next video inside of this series—the diagonal spread. We are going to cover the diagonal spread now, guys. This is probably my favorite low IV environment strategy. The flexibility, the adaptability is second to none. So let's follow the same structure as what we've done so far: let's talk about winners, let's talk about losers, and let's talk about everything in between. But before we do,

let's remind ourselves how a diagonal spread sets up. All right, so how does a diagonal spread set up? Well, first, let's remember that a diagonal spread is kind of a hybrid strategy; it is part vertical spread and it is part calendar spread. So you have both a directional component and a time component. What that means is if you get the stock move that you want, then you can get paid very quickly. It also means that you can benefit from the simple passage of time. Now our diagonals are always debit strategies. So what that means is

this: if you are bullish, you want to use call options; if you are bearish, you want to use put options. The way it sets up is as follows: you want to go into the back month, and you want to buy an option that is a couple strikes in the money. Then you want to step into the front month, and you want to sell an option that is a couple strikes out of the money. Now that's probably about as clear as mud, so let's work through a couple of examples. Let's suppose that you are bullish on

Apple, and Apple is currently selling for $130. The front month is February, and the back month is March. What you might want to do is go into March and buy the 128 strike call—that's a couple strikes in the money. Then you go back into February and you sell maybe the 132 strike call—that is a couple strikes out of the money. This would give you a $4 wide diagonal spread. Or let's say you're bearish on the overall market. Let's say you're bearish on the SPY. SPY is at $350; the front... The month is still February, and

the back month is still March. The way you could set this guy up would be going into March and buying maybe a 353 put that is a few strikes in the money. Then you step into February and maybe you sell the 348 put that is a couple strikes out of the money. Here you would have on your hands a $5 wide put diagonal spread. Either way, guys, call diagonals, put diagonals, upside, downside, bullish SPYs—I don't even care about any of that. Here is the most important part of the whole puzzle: you don't want to overpay

for your diagonal spread. You don't want to pay more than 75% of the width of the spread. So, on our $4 wide diagonal in Apple, that would be about $3; on our $5 wide diagonal in SPY, that would be about $3.75. Why is it so important that you not overpay for your diagonal spread? Well, you need to remember that the width of the spread less the debit that you've paid—that's your profit potential. So, on that $4 wide diagonal in Apple, you pay three bucks; the maximum profit on that strategy is $1. If you overpay—if you

pay too much for your diagonal spread—you might find yourself having gotten the move that you wanted, and you didn't even make any money. You're not even profitable, and you're just left scratching your head. So, by all means, tinker with the strikes, play around with it a little bit until you get the risk-return trade-off that you want, but if it doesn't set up, then it doesn't set up. Just walk away and find something else. All right, so that's how a diagonal spread sets up. Now the fun part: the winning trades. How do we manage these guys?

Well, it's actually pretty simple, and it's very similar to everything we've done to this point. We set our profit target right at about 50% of maximum profit. So again, on that $4 wide diagonal spread, you pay three bucks; your maximum profit is $1. You're only looking to come away with 50% of that, so about 50 cents. That would be a winning trade. You book it, you close it, you move on, you find another opportunity. All right, so now unfortunately, not-so-fun stuff: those losing trades, right? You put on a call diagonal and the stock goes down.

You put on a put diagonal and the stock goes up. What do you do? Well, this is the true beauty of the diagonal spread because, remember, you have distance between your short option and your long option—you have options, pun intended. All right, so you've basically got three options here: Number one, you could roll that short option forward into a weekly cycle and create for yourself sort of a mini diagonal spread. You'll be able to do this for a credit; this is probably the most standard adjustment to a diagonal spread. Number two, you could roll forward

into a mini diagonal spread, but simultaneously you roll your short strike in, thus shrinking the width of the diagonal spread. If you choose to do this, you will aggressively collect more credits, but you need to be mindful that you don't shrink the width so far that the net debit that you've paid exceeds the width of the diagonal spread because if you do that, you will be locking in a loss. Number three, you could also roll the short option all the way into the back month with the long option, and this would create for yourself a

vertical spread in that back month cycle. Okay, so when do you make these adjustments if you don't get the move that you wanted? Well, this is largely going to be up to your discretion, but usually no sooner than 21 days to go and possibly even later in the cycle because this is a defined risk strategy where your maximum loss is approximately the cost that you've paid for the diagonal spread. All right, so those are winners, those are losers. What about everything in between? What about when you get to 21 days to go and you're kind

of even? What about when you get close to expiration on that short option and you're kind of at a scratch? What do you do? Well, this is very, very simple: roll that short option forward into a weekly cycle and go for that mini diagonal. Man, unless your directional bias has changed, take full advantage of the flexibility that you have with this strategy. All right, guys, that's it! We made it to the end. That is the diagonal spread in 8 minutes or less. I will see you in the next video, which is going to be our

first undefined risk strategy with the short strangle. We are going to dive into the undefined risk category, and we're going to do so headfirst with the short strangle. We're going to follow the same protocols as what we've done with all the other videos up to this point: we're going to talk about managing winners, we're going to talk about managing losers, and we're going to talk about everything in between. So let's do it, and let's begin with the structure of a short strangle. So, the short strangle is one of the simplest undefined risk strategies that you

could select. It consists of two legs: an out-of-the-money short call above the current stock price and an out-of-the-money short put below the current stock price. That's it! Now, on entry, there are a few things that you want to look out for. Number one, since this is a short premium strategy, it is best suited for a high implied volatility ratio (IVR) environment. Now ideally, this would mean an IVR that's greater than 50, but at times, an IVR that's maybe 25 or 30 might... Be high enough. There is definitely some flexibility here. Number two, and specifically two

strangles, we want to make sure that we collect enough on entry. We typically set our minimum bound around $1 across both the put and the call, and the reason why is very simple: this is an undefined risk strategy, so we want to make sure that we are fairly compensated for taking all of that risk. Number three, also specific to a strangle, a great starting point for your strike selection would be somewhere around the 16 Delta mark: a 16 Delta short call and a 16 Delta short put. This is a classic one standard deviation strangle. Use

this as a reference point to determine where you want to select your strikes. You may want to collect more premium, you may want to increase or decrease your probabilities—that's perfectly fine. But starting with the one standard deviation strangle is a really great foundation. All right, so now we know how these guys set up, let's get to the fun stuff: managing those winners. This is going to be pretty simple. This is going to be the same procedure that we have followed with our other short premium strategies, short verticals and iron condors. We take these guys off

at 50% of max profit. So, for example, if you sell a strangle for $2, you're looking to buy it back for $1. If you sell a strangle for $1.50, you're looking to buy it back for $0.75. It really is that simple. The one thing that you want to make sure that you do here, though, is don't take the legs off separately; don't leg out of the trade. Our research has shown there's no long-term benefit to doing this, so keep it very simple: take it off as a package. All right, what about these not-so-fun guys? What

about these losers? Well, I hope you have your Powerade Zero handy because you're going to need those electrolytes. This is going to be a lot. First up, if the stock is between your short strikes, don't do anything. If the stock is between your short strikes, even if it's moving around a lot, the strategy is working. Let it work. It isn't until one of the short strikes gets hit that the adjustment protocol to follow is triggered. All right, so what happens when the stock rallies and your short call gets hit, or the stock falls and your

short put gets hit? It's basically a three-step process with a four bonus step that you can execute at your discretion. So, let's get into it. All right, step one: you roll the untested side into a tighter strangle, where your objective is to reduce the magnitude of your deltas by 30 to 50%. So, for example, let's say you put on that one standard deviation strangle to begin with, so you're pretty delta neutral on trade entry. Let's say the stock rallies up to your short strike or maybe through your short strike. Now your position deltas might be

around minus 50 deltas. What you would want to do is roll that short put up until you have trimmed the magnitude of those bearish deltas by 30 to 50%. So if you're at minus 50, maybe you're looking to reduce your deltas to minus 25 or minus 35—somewhere around that 30 to 50% magnitude reduction. The same would be true if the stock fell; you would roll your call strike down to again reduce the magnitude of your bullish deltas in this case by 30 to 50%. All right, so what if the stock still continues to move against

you? This is where you go to step two: you roll that untested side into a straddle. Now, if the stock is continuing to rally, you're going to roll that short put strike all the way up until it shares the same strike as your short call strike. If the stock is falling, then you would roll the short call strike down all the way to share the same strike as the short put strike. All right, but what if that's still not enough? What if the stock continues to get away from you? The stock continues to move against

you. You go to step three: you're going to want to go inverted with your strangle. This means you roll your put strike up above your call strike if the stock is rallying, or you roll your call strike down below your put strike if the stock is falling. Doing this will really help to control and mitigate your directional exposure on the position. Now, naturally, if I was in your position right now, the number one question that I would have is, "All right, Jim, how do I know where to set my inverted strike?" Well, to be honest,

there is a lot of discretion that you're going to need to apply. There's plenty of pros and cons, plenty of gimmies and gotta's that you need to consider. But here's a great reference point: consider moving your inverted strike to the new at-the-money strike. The reason why this is a great reference point, a great anchor in the sea, if you will, is the at-the-money strike always has the greatest amount of extrinsic value. So if you move to that strike, you can be assured that you are maximizing the extrinsic value that you are collecting on the trade.

What you really want to be aware of here is the width of the inversion relative to the credits that you have collected, because your best-case scenario now is the stock stays between your two short strikes and the two options are in the money, so you can buy back that strangle for the width of the inversion. So, for example, if you have a $5 wide inverted strangle and you've collected $7... If the stock were to expire inside of those two short strikes, both options would be in the money. The total intrinsic value would be the width

of the inversion. For $5, you collected $7, so you would end up netting a positive $2 profit on the trade. Therefore, you always want to be aware of this relationship because things are a little bit different now from what they were with a regular strangle. All right, now that fourth step that I promised you: the bonus step. You can always roll out in time; you can always add duration to the trade, and you can do this whenever you see fit. You can combine it with step one, you can combine it with step two, and you

can combine it with step three. So how do you know when is the best time to pull the trigger on this bonus step? Well, remember, we typically like to keep our short premium trades around 45 days to go. So if they're still around 45 days to go in the current cycle—like 47, 43, 40, or 39—then I would consider sitting tight. But if you've gotten to a point where there aren’t close to 45 days to go, maybe you're at 21, maybe you're at 25, or maybe you're at 30, this might be a really good time to

roll this position out, add that duration, and use this bonus step. Now, a quick disclaimer: that entire protocol is a great guide to follow, and the reasons why are these: all along the way, at every step in the process, you are collecting credits, you are reducing risk, and you are widening your break-even points. But is this the only way that you could adjust a short strangle? Absolutely not. Are there other viable, successful ways to adjust a short strangle? Absolutely. But if you are brand new, if you are just gaining experience, and you are just getting

your feet wet, then start here. As you get some more exposure to the markets and as you gain that experience, by all means, man, tweak it, tinker with it, and make it your own. All right, lastly, what about that dance floor? What about those trades that aren't really winners? They're not really losers; they're just kind of hanging out somewhere in the middle. Well, this is pretty simple, and it's going to be very similar to what we've done with our other short premium trades: the short vertical, the iron condor. Look at IVR. If IVR is still

high, if it's still elevated, then consider keeping it on. But if IVR has come down, if IVR has collapsed, then consider taking it off. All right, guys, man, you made it! That was a lot. When you are ready, I will see you in the next video. The short put: we are going to cover the short put, which is actually a bit of a downtick in difficulty from the short strangle that we just did in the last video. So that's pretty good. We're going to follow the same protocol that we've been doing: winners, losers, and dance

floor. So let's begin with how a short put sets up. All right, so structurally, strategically, a short put is actually pretty straightforward. First, it's only a single leg, so that's pretty nice. But second, we are almost always going to choose an out-of-the-money strike on trade entry for a new position. The reason why is very simple: by choosing an out-of-the-money strike, we leave ourselves room to be wrong directionally and still make money. That alone is an extremely powerful phenomenon. For example, let's say you've got Starbucks at $100 a share. You want to sell a 95 put.

Here is how a short put would set up: if Starbucks goes higher, you're going to make money; if Starbucks goes nowhere, you're going to make money. But even if Starbucks goes down a little bit but stays above that 95 strike, you are still on the path to making money in a market that is very unpredictable and totally random. In the 45-day time horizon, this is very, very advantageous. All right, so that's how a short put sets up. Now, what about these winners? This is pretty straightforward because it's going to be the same as what we've

seen with everything up to this point with vertical spreads, iron condors, diagonals, and short strangles. We want to target 50% of max profit. So if you sell the short put for two bucks, you're looking to buy it back for a dollar. If you sell a short strangle, a short put for $1.80, you're looking to buy it back for 90. It's really that simple. That's all there is to it. Okay, so now on to these losers, the not-so-fun guys. This is where things can get a little bumpy, so you might want to buckle up. And of

course, this is not the only way that you could handle these situations, but I do think it makes a little bit of sense. First up: as long as the stock is above your short strike, as long as the stock is above your short put, doing nothing is almost always the move to make. It doesn't matter how you feel; it doesn't matter what you think—doing nothing is the move. Okay, but let's say now the stock has fallen down to your short strike. Now what do you do? Well, it really depends on the severity of the move,

right? Like, if the stock is now just below your short strike, then you probably only need to roll out in time, right? Push this thing out to the next cycle, add some duration, pick up some extra intrinsic value, widen out those break-even points, and you're probably going to be okay. Okay, but what if the stock has fallen kind of significantly? Below your short strike, now what do you do? Well, first off, as an initial line of defense, you probably want to go ahead and roll out in time. But also, as a secondary line of defense,

you might want to consider adding a short call at the same strike as your short put. This would create for yourself, of course, a short straddle, and it's going to effectively serve the same purpose as rolling out in time. You're going to pick up more extrinsic value, and you're going to help to widen out those break-even points. But there's another benefit: adding those bearish deltas from the short call will help to flatten out your directional risk, flatten out your directional exposure from the deep in-the-money or somewhat in-the-money short put that you have. And those bullish

deltas will allow you to focus more on non-directional elements like theta, like vega, and less on delta. Okay, but what if the stock has fallen way below your short put strike? Now, again, first off, roll out in time, add that duration, pick up the extrinsic value, and widen out those break-even points. But also, adding a short call— you probably don't want to go to the straddle strike now; you might want to be a little bit more aggressive. You might want to go right into an inverted strangle, so your short call strike will be below your

short put strike. This will help to more aggressively neutralize those deltas while still bringing in credits, adding extrinsic value, and widening out those break-even points. The thing you want to be aware of here, and you want to be careful of, as we saw in the short strangle video, is you just want to make sure that the width of your inversion is less than the total credits that you've collected, so you're not locking in a loss for this cycle. Okay, so now that you've made these adjustments, how do you know when it's time to get out?

How do you know when it's time to exit a short put or any undefined risk strategy, for that matter? Here are some good rules of thumb: if your position was a loser—which is almost always going to be the case in this scenario—if you can work that thing back to a scratch, if you can work that thing back to even, then I would strongly consider taking it off. Turning a loser into a scratch is basically like a winner at the end of the day. But what if this thing never comes back? What if the stock never

cooperates; the position never accommodates you, and this thing just becomes a runaway train? Somewhere around 2X to 3X of total credits received is a good place to consider exiting your trade if you don't want to hold it anymore. So just to be clear, as an example, let's say you sell a put for $2. Then you make a couple of adjustments, you add some time, and your total credits collected become $5. If you close that trade, if it never comes back and you close it for $15, that is a 2X loser. You collected $5, and you

lost $10; that's a 2X loser. If you were to close it for $20, that would be a $15 loser or a 3X loser. All right, so those are the winners and those are the losers. But what about the dance floor? What about those in-between guys when it comes to a short put? Well, as is the case with all undefined risk strategies, we don't want to carry these inside of 21 days to go. So if you still have this on at 21 days to go, the choice becomes simple: you either roll it or you close it.

If implied volatility rank (IVR) is elevated and you still like your bullish bias, then consider rolling it. If IVR has fallen and you don't like your bullish bias, then consider closing it. Well, what if IVR has fallen and you still like your bullish bias? Well, that's your call. All right, guys, you made it! That is the end of the short put video. Be sure to save this video for future reference, and when you are ready, I will see you in the next video on short straddles. We are going to continue with our undefined risk category

today, and we are going to specifically cover the short straddle. Now, as you're going to see, this is going to be a little different from what we've covered thus far inside of the undefined risk category, so pay close attention. We're going to do this the same way that we've done it to this point: winners, losers, and then the dance floor. So let's begin with how a short straddle sets up. Okay, so a short straddle actually sets up very similarly to a short strangle. You have two options: you have a short put and you have a

short call. The key difference here, though, is that with a short strangle, we saw that there was some distance between the short put and the short call. But with a short straddle, they're actually going to share the same short strike, and that short strike is usually going to be situated right around where the stock price is to create that neutral directional bias. So, for example, if the stock price was 100, you would do a short put at 100 and a short call at 100. If the stock price was 45, you would do a short put

at 45 and a short call at 45. Now, to be fair, naturally, if I heard that, if I was on your end of the information today, my question would be: Jim, why in the world would I do that? Why in the world would anybody not have any distance between their... Short strikes—well, the answer, or at least part of the answer, is this: remember that the at-the-money strikes always carry the greatest amount of extrinsic value. So, by choosing to sell your strikes there, you are maximizing the short premium that you collect. Okay, so that's how a

straddle sets up. Now, on to the fun part—those winners! How do you handle those straddles that are profitable? Well, this is actually going to be different from what we've seen in the previous six videos. We're going to target a smaller percentage of max profit. We're only going to target 25% of max profit, and the reason why is this: yes, it's true that the at-the-money strikes command the greatest extrinsic value, but they also cling on to that extrinsic value the longest. So, we combat this by more aggressively managing our winners at a smaller percentage of max

profit—25% relative to 50%, like we've seen with the other strategies. So, for example, if you sell a straddle for $5, we would be looking to take off about $1.25, or 25% of that. If you sell a straddle for $3, we will be looking to manage that winner at about $0.75. All right, so now on to the not-so-fun stuff—how do we handle those losers? Well, similar to a strangle, this is going to be kind of a step-by-step process. As long as the stock is between your break-even points, you sit and you do nothing. Since we have

that shared strike, one of our strikes is always going to be in the money, so we can't use the distance between the short strikes as our reference point. Instead, we use the break-even points. As long as the stock is between those two markers, the strategy is working, and your best bet is most likely to do nothing. So, for example, if you sell the 50 straddle for $5, let's say your upside break-even is 55 and your downside break-even is 45. Those become your two markers for knowing when it's time to adjust your strategy. Okay, but now

let's say one of your break-evens does get hit, whether it be on the top side or the bottom side—what do you do? Well, first, a quick little disclaimer: this is of course not the only way that you can handle a short straddle and its adjustments, but I do think it's a pretty good foundation. Similar to what we saw with a strangle, this is going to be a step-by-step process. The key difference here, though, is we don't have as many adjustments available to us as we had with the strangle, because we're already starting in the straddle

position. Since we're already in a straddle position, we basically only have two adjustments available to us: we either roll out or we go inverted. So, how do you know which of the two to choose? Well, take a look at how much time is left in your cycle. Again, if you are close to around 45 days to go, the move might be to go ahead and go inverted. Follow the same protocols that we've laid out in the previous two videos with short puts and short strangles. Start with that at-the-money strike because it has the greatest amount

of extrinsic value, and then make adjustments from there. The one thing that you want to be aware of, of course, is the credits you've collected relative to the width of inversion. Now, if you happen to be closer to 21 days to go, then roll out in time first. Go to that next cycle, add duration, and pick up that extrinsic. And of course, don't forget if at any point in time you want to more aggressively reduce your risk and improve your basis, then you can do both: you can go inverted and roll out in time at

the same time. Okay, now as far as when to call it quits, when to wave that white flag—well, as we've seen in the last couple of videos, if you want to manage your losers, somewhere around 2x to 3x of total credits received is a great starting point. So, for example, if you've collected $7 in total on your straddle and all of its adjustments, then buying it back for $21 would be a 2x loser; buying it back for $28 would be a 3x loser. If, however, you collected, let's say, $9 on your straddle and all of

its adjustments, then buying it back for $27 would be a 2x loser, and buying it back for $36 would be a 3x loser. All right, so those are the winners, and those are the losers. But what about everything in between? What about that dance floor? Well, this one's pretty simple because it's the exact same as what we've seen so far. Look at IVR. If IVR is still elevated, then consider keeping it on. If IVR has collapsed, then consider taking it off. All right, so that's it! The short straddle is now in the books. I will

see you in the next and final video on the ratio spread. We are going to cover the ratio spread, and we're going to follow the same protocols that we follow to this point. We're going to cover winners, we're going to cover losers, and we're going to cover that dance floor. But first, let's talk about how a ratio spread sets up. The ratio spread—this is arguably the most versatile, most flexible strategy that is available to us, and it consists of two parts: you have one long option and you have two short options. The long option is

usually situated at the money or slightly out of the money, and the two short options are then placed further out of the money. Money, and because you have two short options relative to every one long option, this is going to be a net credit strategy. So, for example, let's say that the stock was at $50. You might set up a put ratio spread using the 49 strike and the 48 strike. You would buy a put at the 49 strike and then sell two puts at the 48 strike. But let's say the stock was $75. You

might set up a put ratio spread using the 75 and 72.5 strikes. You would buy a put at the 75 strike, the at-the-money strike, and then you would sell two puts at the 72.5 strike, the out-of-the-money strikes. Now, there are a few things that you want to be aware of, that you want to be cognizant of when it comes to putting on a ratio spread. First, the wider you go with your ratio spread, the greater your maximum potential profit. This is because the vertical spread that's kind of baked into the center of the ratio spread

could potentially be worth more money. The trade-off here is that the wider you go with that ratio spread, the lower your credits collected. Second, you want to make sure that you collect a credit that is economically significant. You'll see why in a couple of minutes. Third, we typically prefer put ratio spreads over call ratio spreads, and this is for the same reason that we typically prefer short puts over short calls—the market wants to go higher over time. Battling a short call over cycle after cycle after cycle in a market that wants to grind higher can

really be a stick in the mud. All right, so managing winners—everybody's favorite. This is actually going to be a little bit more involved than what we've seen to this point, and that's because with a put ratio spread, you can actually make money in both directions. If the stock rallies, then you're going to keep the credit collected because those options are going to move further out of the money. But if the stock falls, then you could potentially make more money. This would happen at expiration if you pin that short strike. You'll keep that credit collected, but

you'll also pick up the width of the ratio spread. Since we don't hold our undefined risk trades inside of 21 days to go, we're actually not super interested in that stock falling scenario since that's never really going to come into play. So we want to focus our energies on the stock rallying scenario. How do we manage those winners? Because ratio spreads are so versatile and they are so flexible, you're going to have to use a lot of discretion in handling these situations. But if the stock does rally and the options move further and further out

of the money, you're going to want to look to capture most of the credit that you have collected. So, for example, let's say you put a ratio spread on at entry for 60. If you can buy that thing back for 20 cents a week later, then you might want to consider doing that. Let's say you put a ratio spread on for 90 cents. If at some point in the future you can buy that thing back for 30 cents or 33 cents, you might want to consider that one too. Again, there's no hard cut-off point here,

so you're going to have to use your experience as your guide. But do you remember when we said it needs to be economically significant? This is why you want to put yourself in a position to where, if the stock does rally and your P&L approaches that credit collected, it is meaningful. All right, so now what about those losers? Well, our reference point for adjusting is going to be that short strike. As long as the stock is above your short strike, then you do nothing—easy enough. But now, what do you do if the stock does fall

down through your short put strike? How do you handle that situation? Well, the first thing you're going to want to do is check the value of the vertical spread that is baked into the center of the strategy. If you can take that off for nearly max value, then go ahead and take that off. So, for example, if you have a $1 wide ratio spread, then the vertical spread that's in the center is $1 wide. If you can take that off for 85 cents, that's almost max value. If you have a $2.50 wide ratio and you

can take off the vertical spread for $2, that's also almost max value. Now, where is the cut-off point for determining if it's enough on the vertical spread to take it off? Well, that's largely going to be up to you, but I can tell you what I do: If I can't get at least 80% of the vertical spread's value, then I do not take it off. If you are able to close out of that long put vertical for near max value, now all you have left is a short put, so manage it in the same way

that we did in the short put video. Just keep in mind that now your total credits collected are the credits on order entry and the credits from selling out that vertical spread. Okay, but what do you do if you can't close out of that vertical spread for near max value? Well, you basically have two options. First option: you sit and you wait; you do nothing. You can do this here because either one of two things is going to happen: A, the stock goes down. If the stock goes down, then that vertical spread is going to

increase in value and... You're going to be able to close it down; you close it down, you manage that extra short put accordingly, and you move on. Or B, the stock actually rallies. If the stock rallies, then those options could be out of the money again. This is an even better scenario. But the second option, of course, is you can roll the whole thing out in time. You can pick the whole thing up: the short put, the vertical spread, all the pieces, and roll it out in time. If you do this, you will reduce your

risk and add duration to the trade. All right, easy enough. But what do you do if the stock just keeps falling? What do you do if, no matter what you do, the stock will not come back? Well, again, remember: if you choose to manage your losers, somewhere around 2x to 3x of total credits received is a really good marker. So, for example, if your total credits from order entry, from rolling out, or from closing out that vertical spread—if all of these credits were $4, for example, buying it back for $12 would be a 2x loser,

and buying it back for $16 would be a 3x loser. All right, so those are the winners, and those are the losers. But what about everything in between? What about that dance floor? Well, since you have that extra short put, and this strategy is so flexible, rolling out in time as your default option is not a bad move. But remember, you can always use IVR as your guide. If IVR is still elevated, then keep it on. If IVR has fallen, then take it off. Wow, you guys made it! The options crash course strategy series has

now come to a close. I sincerely hope that you guys got some value from these videos. So that is it, and I will see you guys next time.

Vidéos connexes

1:22:46

Every Options Greek (and how to use them) ...

tastylive

28,337 views

31:31

How This Professor Unlocked a Winning 0 DT...

tastylive

84,892 views

41:24

These 4 Lessons Allowed Me to Stop Trading...

tastylive

116,436 views

47:44

Ranking Option Strategies Based On Risk | ...

tastylive

73,887 views

![Options for Beginners [2025]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/89NHBLDTQyk/mqdefault.jpg)

1:56:35

Options for Beginners [2025]

tastylive

181,418 views

1:29:00

Tom Sosnoff a Strategic Finance for the Pr...

FAU Business

68,532 views

52:56

The BEST 0DTE Strategies for Profit with T...

OptionsPlay

81,672 views

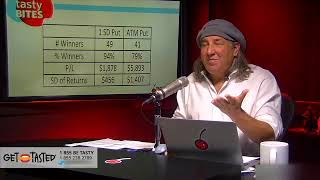

34:01

Dan talks with Tom on How He Manages & Sel...

Sheridan Risk Management

38,038 views

48:36

48 Minutes of Trading Advice You Wish You ...

tastylive

105,433 views

14:28

We Compared This Dip To 2008... The Simila...

tastylive

18,354 views

17:55

Small Account Options Income Strategy (Easy)

SMB Capital

438,395 views

26:29

Tom Sosnoff's Complete Guide to Options (f...

tastylive

152,668 views

1:03:02

The Blueprint to Tom Sosnoff's Ideal Portf...

tastylive

65,796 views

50:02

Deep In The Money Call Options - Why They'...

Lee Lowell - The Smart Option Seller

66,273 views

1:01:29

Tom Sosnoff: How To Trade Earnings Moves I...

Investor's Business Daily

29,467 views

27:09

'Go Naked' - Finance Professor's Strategy ...

tastylive

110,302 views

1:00:04

The ONLY #1 Options Strategy You May Need ...

OptionsPlay

106,559 views

32:06

Trading Took This 9-5 Employee To A Full T...

tastylive

36,860 views

12:01

Selling Put Options in $10,000 (or less) T...

tastylive

465,016 views

14:02

4 Steps to Start Trading In a Small Account

tastylive

59,711 views