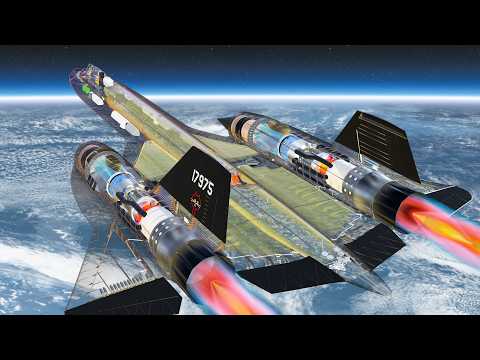

How the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird Works

6.54M views6035 WordsCopy TextShare

Animagraffs

An intensive and thrilling look inside the SR-71 Blackbird, one of aviation's absolute greatest lege...

Video Transcript:

I'm Jake O'Neal, creator of Animagraffs, And this is the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. The SR-71 entered service in the United States Air Force in 1966 as a reconnaissance aircraft, or in other words, a spy plane. It doesn't carry bombs or have onboard guns.

Its main defense against enemy action is altitude and speed which made it essentially invulnerable, sustaining Mach 3. 2, that is 3. 2 times the speed of sound which roughly correlates to about 2,200+ miles per hour (3540.

6 km/h), at altitudes up to 85,000 feet (25,908 m). No SR-71 was ever shot down. To evade missiles or hostile aircraft, if they could even reach the SR-71's altitude, pilots simply outran them.

Every part of this masterpiece is designed for its mission goals. Let's have a general look around the plane to get an idea of how those goals translate into the physical design of things, before we zoom in on the finer details of each system. The Blackbird is a relatively large airplane compared to other fighter or reconnaissance craft of the era.

Flying at untouchable altitudes and speeds simply requires a lot of fuel. Two-thirds of the fuselage are occupied by cylindrical fuel tanks, and any usable space in the wings, for a total capacity of 12,219. 2 gallons (46,254.

7 L), weighing in at around 80,285 pounds (36416. 7 kg) of fuel. A pair of powerful jet engines are secured into the wings at both sides.

A substantial portion of this compartment, called the nacelle, is dedicated to large movable inlet cones called "spikes" which, as we'll see later, are critical for the SR-71's supersonic speed capabilities. A row of flaps along the back of the wing, called elevons, and rudders perched atop each nacelle, make up the flight control surfaces for the plane. Heading to the front, there are two cockpits for the pilot and Reconnaissance Systems Officer respectively.

Equipment bays surround the cockpits and can be fitted with an array of components depending on the mission, as well as the removable nose section. Now let's get into the details, starting with the exterior aerodynamics. The engines appear to be tilted slightly downwards on the ground.

At cruising altitude and speed they're closer to level, with the fuselage and wing designed to sit at 6 degrees positive rotation or "angle of attack". To carry sufficient fuel, equipment, and personnel, the fuselage and nose of the plane is quite long. The Blackbird has a delta wing design, so called for its triangular shape like a greek delta character.

Exceeding the speed of sound, or "going supersonic", as the SR-71 was designed to do means pushing hard against air molecules. Air molecules are real physical things, bonded together in a sort of elastic mesh, and sound happens when those molecules ram into each other, to eventually physically jiggle your ear drum. The spacing of these molecules, their individual weight, the strength of the elastic bonds between them, and so on, gives this air mesh predictable behavior.

If you slam through these molecules faster than they can crash into themselves, you're exceeding the speed of sound. On the ground, this happens at around 760 mph (1,223 km/h) in relatively normal conditions. Since they can't move out of the way fast enough, air molecules bunch up when they hit parts of the plane that stick out, forming shock waves that have predictable characteristics.

Like angles that get sharper with increasing speed. 18 degrees, to be precise, at Mach 3. 2 cruising speed.

Let's throw a more standard wing into the mix. Because these wings have much less sweep back angle, the nose shock wave blasts into them, causing a brick wall of drag to slow the plane down. If you try to sweep them back far enough to tuck into the nose shock wave, the attachment point at the fuselage gets flimsy.

Notice how the delta wing solves these issues. The classic aerodynamic wing profile shape is excellent for generating lift at slower speeds. But as we approach supersonic speed, its thickness and blunt leading edge cause air to bunch up in front of the wing in a turbulent traffic jam Contributing to what's called the "sound barrier".

In contrast, as pressure builds with increasing speed, the SR-71's sharp, thin wing slices through the air. The narrow leading edge allows the developing shock wave to eventually attach itself to the front of the wing. At the speed of sound and above, the plane's sharp features comb air into smooth flowing, well behaved supersonic shock waves at leading and trailing edges The twin jet engines and their inlets are spaced out from the center to avoid air that swirls up from under the fuselage, but are still kept within the nose shock wave even at maximum speeds.

As we continue observing the exterior, we see the characteristic ridges at each side of the fuselage. In aerodynamic parlance, a sharp edge like this is called a chine. These chines serve a few critical tasks.

They help form more powerful vortices as air swirls up around them during flight, which causes lower pressure above the sharp thin wings, contributing an impressive 20% of total lift at speed. They act like fins to stabilize the blackbird's long nose as it cuts through the air. These chines also greatly reduce the radar cross section.

Radar towers beam signals from a point outwards. Common rounded plane features will reliably reflect some of those waves back for easier identification from many angles. The Blackbird's flatter surfaces reduce the likelihood of waves reflecting back to the source.

The rudders are also tilted or canted inwards for the same reason. Its radar cross section makes it look much smaller than it is. The SR-71 was among the first operational aircraft with this kind of intentional stealth shaping.

The Blackbird also featured an early radar-absorbing composite material, called plastic (though not what we think of as plastic). Composite wedges alternate with titanium along the outer rim in a zig-zag pattern to allow for expansion. This so-called plastic also covers inlet cones and rudders.

The interior frame, called the airframe, is mostly made of titanium, as well as much of the exterior paneling, for its performance under extreme stress and heat. Some surfaces could reach 700+ degrees F (371 C), and the entire plane expanded several inches when traveling at speed. Corrugations along the wing surface also allow expansion while contributing strength.

Now that we've seen how the exterior shell and underlying airframe are made for supersonic flight, let's see how the engines get us there. We'll zoom in on just one side. There's the inlet spike at the front, which we'll get to in a bit.

The actual jet engine sits behind that, and has a pretty standard overall design. Air enters the jet engine and is forced backwards by rotating discs with blades, called rotors. Rings of stationary blades called stators make sure the air flows generally backwards and builds pressure, instead of just twisting with rotors.

The passage narrows, compressing the air for more powerful combustion. The compressed air now flows through separate nozzles, around a small outer ring while fuel is sprayed through the center. The fuel-air mixture is ignited.

In many jet engines, ignitor plugs, not unlike a car spark plug, are used. But the SR-71 is different because of its special fuel that has its own ignition requirements. We'll look at that a little later.

Once ignited, flame passes through small "cross-over" tubes until all burner cans are lit. The powerful exhaust shooting out of these cans pushes against turbines, delivering something like 60,000 horsepower Turbines are connected to internal gears and shafts to drive those forward compressor rotors, sucking in more air and continuing the cycle. The exiting hot exhaust gas expands, creating a fast moving jet of air to push the plane forwards.

This setup, with compressor, combustor, and turbine sections, is the basic turbojet engine design. Animagraffs has a video about jet engines if you want to see how this looks in a big airliner, or a more modern fighter jet. High performance engines often have an afterburner section, and the Blackbird does as well.

Fuel has been consumed, but there's still burnable air in the exiting exhaust stream. Additional fuel is sprayed into this stream. The mixture wraps around V-shaped rings called flame holders, which provide a contained area of turbulence for fuel mixing and combustion.

This mixture is ignited For most applications, afterburner is fuel inefficient but very powerful. As such, it's limited to short bursts. In contrast, the Blackbird is designed to maintain continuous, full afterburner at cruising speed, for an hour or so at a time between aerial refuelings.

All this heat and built up pressure must now be converted into exhaust velocity. There's a special section here called a converging/diverging nozzle. Hot, pressurized jet exhaust speeds up to squeeze through the narrow part, and then expands through the wide exit, converting all that heat and pressure into velocity.

There's a ring of flaps called the "ejector" that can alter the size of the exhaust opening for proper exhaust acceleration in varying conditions. There are free-floating ejector flaps that adjust based on the pressure difference inside vs. outside the exhaust duct Accelerating exhaust is something like sticking your thumb over a garden hose.

Water still in the hose moves slowly and pushes harder against hose walls the more you block the stream for a stronger spray at the end. In hard numbers, if air exiting the turbines is at Mach 0. 4, air at the ejector flaps has accelerated to Mach 3 or more, to match the plane's traveling speed.

This late 1950's fighter jet technology is awesome, but it's not capable of sustaining Mach 3. 2 on its own. In fact, the jet engine can't even use supersonic air as it would cause flameouts, extinguishing the combustor, among other things.

This is where the inlet spike comes into play. A supersonic shock wave forms at the sharp tip of the spike, tuning airflow for entry into the inlet chamber. Some compression is already happening here, outside of the nacelle.

Just at the inlet lip, another shock wave forms, bounces or "reflects" a few times, and eventually reaches the narrowest part of the inlet passage, where its supersonic energy is finally converted, having slowed to subsonic speeds. The tremendous exchange of energy that happens as supersonic air trades its velocity for increased pressure, density and temperature, is key. You can't use supersonic air in the jet engine, but you can use the jet engine like a pump to take in more and more supersonic air and convert it to pressure.

It's the garden hose in reverse, if the fast water stream could be crammed back into the hose. To that end, there's an opening just before the inlet's narrowest point, to bleed off some supersonic air. It flows through shock traps to slow and pressurize.

It surrounds and cools the engine, and eventually rejoins the exhaust stream, where it trades pressure for velocity on its way out the back. This process is so important that at Mach 3. 2 cruise, just the pressure recovery alone from the inlet spike and bypass air is responsible for an incredible 58% of thrust.

This clever trick is also possible because there's less air pressure at 80,000 feet, so you don't need to hold or build up as much pressure inside the engine to release a super fast exhaust jet. At sea level the air is much thicker. Imagine that same garden hose, but spraying underwater.

The spike is adjustable. With this much thrust coming from the inlet spike at such high speeds, it's critical that shock waves maintain proper alignment. At Mach 1.

6 the spike begins to retract and continues moving backwards, to 26 inches (66 cm) of rearward travel at its limit as speed hits Mach 3. 2, the Blackbird's designed cruising speed. The inlet throat's shape changes as the spike moves.

At cruise, the spike shock wave sits right at the inlet lip. Again, keeping this pre-designed shock wave pattern is crucial. For example, say some kind of internal error causes pressure build up at the mouth of the jet engine, pushing shock waves out of alignment.

All that thrust is immediately lost, and the plane jerks abruptly to one side, slamming pilots helmets against cockpit windows. This is called an inlet unstart. Unstarts were harrowing experiences for SR-71 pilots.

With up to 70% of total thrust disappearing in an instant. If an unstart is detected, the onboard computer moves the spike forward in an attempt to restart it. So that's it.

You've got the famed J58 jet engines for getting the Blackbird off the ground and up to speed, and the inlet spikes for comfortable cruise well into the supersonic realm. This system is so good at capturing the energy in supersonic airflow that the Blackbird was known to get better fuel mileage the faster it went. Now, let's examine a few other components at the engine that help keep airflow in check at key points in the system.

There are computer controlled cowl bleed vents to let off excess air from the inlet throat. There are computer controlled forward bypass doors to let off excess air, and keep inlet air pressure balanced However, this slow air rejoining the outside flow could cause drag. So, there's another set of bypass doors just before the engine that the pilot can manually control, which bleed air into the nacelle bypass chamber instead.

Below Mach 0. 5 there may not be enough airflow yet for proper cooling. There are suck-in doors about halfway down the nacelle that open to help out.

There's a set of flaps at the back of the jet engine to independently control afterburner exhaust pressure, and a ring of blow-in doors to help keep the ejector area full at lower speeds and avoid dead spots, which cause drag in the system. Above Mach 2. 2, there are six bypass tubes that open to divert air from the jet engine's compressor section directly to the afterburner, relieving internal engine pressure and boosting afterburner performance.

Up to 40% of the engine intake volume can be bypassed in this way, for a significant thrust increase. The inlet spike has rows of small holes and interior passages that take in cooling air at low speed. At higher speeds, a thin layer of air builds up around surfaces, called the boundary layer.

Boundary layers can do weird things as the air sticks to and follows the surface. At curves, air might separate and clog up the flow, causing unwanted turbulence downstream. These holes bleed off boundary air to keep flow running smoothly.

For weight reduction, there's no starter on the airplane. Start carts were used, with two muscle-car engines placed side by side, without mufflers, running full blast. Crew were said to enjoy the start process for its impressive spectacle.

A shaft with gears extends up and connects with a gearbox at the underside of the jet engine, to get everything spinning and start the combustion process. Now let's move away from the engines, for a look at the fuel system. As shown in the intro, fuel tanks make up a large portion of the plane.

At takeoff, fuel flow rate could reach 74,000 lbs. per hour for a single engine. That's about 3 gallons of fuel per second, or 10,800 (40,882 L) gallons per hour.

At Mach 3. 15, fuel flow is more efficient, at a little under 3,000 (11,356 L) gallons per hour. The tank is incorporated into the wing structure without any additional bladder or barrier.

Since panels were designed to expand, panel gaps meant fuel would leak from the plane when cold. Maintenance personnel had charts for allowable drips per hour, and when that rate was exceeded, the plane's panels had to have sealant reapplied. Surfaces got so hot that normal fuel couldn't be used for risk of auto-ignition from surface heat alone.

A special fuel called JP-7 was developed which wouldn't spontaneously ignite below 466 degrees F (241 °C) To ignite this fuel, a special chemical was required, called triethylborane or TEB for short. TEB, in contrast, ignites on contact with air alone. A shot of TEB was injected first to get the JP-7 fuel burning, which produced the famous green starting flame blast.

Additives in the fuel made it useful as a lubricant, coolant, and hydraulic fluid. It took on any of these roles throughout the plane, especially in the engine's mechanical components. The SR-71 had to refuel shortly after takeoff because the very heavy full fuel load would stress the plane's landing gear and require too much runway for liftoff, among other limitations.

Fueling normally happens at about 25,000 feet (7,620 m), where the plane takes on an additional 60,000 lbs. (27,216 kg) of fuel. There are nitrogen containers in the front landing gear compartment to inert fuel tanks – meaning air is allowed to vent out as nitrogen is pumped in.

With no oxygen near the fuel, it's considered inert, or chemically inactive, greatly reducing explosion risk in conditions of extreme pressure and heat. Flight Control Surfaces Flight control surfaces are parts of an airplane's body that influence airflow to change the plane's attitude. For example, a fairly standard airplane has ailerons at each wingtip that move opposite one another to roll the plane.

Moving elevators at the tail affects pitch, and the rudder controls yaw, or rotation about the airplane's vertical axis. The SR-71 has large dual rudders, one above each engine. The delta wing combines ailerons with elevators into a single row of flaps that handles both tasks.

These are called elevons. Each side moves as a single unit. Opposite one another for roll, and together for pitch – or some blended combination of both for maneuvers that require some roll and pitch at the same time.

To achieve this blended, mixed output, there's a mechanical device in the center tail section called a mixer. Cables from the flight stick in the cockpit pass through pulleys and tubes to arrive at the mixer. There are separate down and back cable runs for stick side-to-side or roll, and stick front-to-back, or pitch.

At the mixer, pitch cables connect to the pitch quadrant, which is a partial wheel with channels and attach points. Roll cables attach to the roll quadrant behind that. There's a mixed output bellcrank at the front with push rods that link to the elevons at either side.

Roll input moves the entire bellcrank left or right. Because linkages are mirrored side to side, this ends up rotating elevons in opposite directions. Pitch input rotates the bellcrank itself, which tilts elevons the same way on both sides.

When pitch and roll commands happen together, the bell crank gracefully blends these commands for a singular output to each side. This beautiful mechanical device is worth a closer look. Take the roll components, for example.

There's a feel spring that compresses to give the pilot felt feedback in the stick for the position of parts in the system, because, as we'll see in a minute, the elevons themselves are hydraulically controlled. There's no direct mechanical connection. Moving down the chain, there's a trim actuator.

Trim adds more permanent adjustment to the system so the pilot doesn't have to hold the stick in one place for long periods of time, for example to fight a continuous side wind. The system still allows moment to moment input on top of the trim setting. The pilot controls the trim level from the cockpit.

Pitch components also have these parts. The pitch feel spring is at the bottom of the mixer. The pitch trim actuator is at the back.

Now watch, as the bell crank executes blended roll and pitch commands, with accompanying trim settings. Also connected to the pitch system, there's a stick pusher. With its own computer controlled actuator.

The stick pusher can shake the stick as a warning, or automatically push the stick forward to avoid or counter a stall. Stalls can happen, for example, if the plane exceeds certain flight angle limits, interrupting lift and causing the plane to fall through the air. From the mixer, rods at each side translate movements to individual servo units.

The servo converts this physical movement into hydraulic pressure to regulate rows of actuators at each elevon. It has a sensing rod to monitor elevon position. From this inboard servo, a train of rods and linkages continues to an outboard servo which controls another set of actuators.

There's a separate set of cables, pulleys, and hydraulic components for each rudder. A rotating post with an attached actuator extends from the rudder stub into the rudder frame. Landing gear There's a single steerable nose wheel at the front, and twin gear at the back.

The peculiar light grey rear tires are made of rubber infused with aluminum powder for a much higher flash point, that is, the temperature at which they could catch fire. They're pressurized to an unbelievable 400psi – your average car tire sits at around 30 to 35 psi. They're also inflated with nitrogen instead of oxygen for fire resistance.

The Blackbird's aerodynamic qualities mean higher landing speeds overall. To further slow the plane down and take stress off the wheels, there's a 40 ft. (12 m) diameter drag chute which is deployed at main gear touchdown, at about 150 knots airspeed.

Now, let's head to the front of the plane for a look inside the Blackbird's dual cockpit(s). The pilot sits in the forward cockpit to fly the plane among other duties, with the Reconnaissance Systems Officer (RSO) in the rear cockpit to run onboard equipment, and direct navigation along the mission flight path. Moving to the pilot's position, let's get into the instruments and controls.

Front and center, there's a grouping of main flight instruments. The attitude indicator shows the plane's position relative to the horizon, with a backup attitude indicator nearby for redundancy. Below that, the HSI or Horizontal Situation Indicator, shows the plane's position relative to a heading or preset point in space, and the plane's relationship to the imaginary line from one heading to the next, including remaining distance, side-to-side deviation, and so on.

Below that, a map projector, which ran on 16mm film, and contains the entire flight route. There are a few instruments here which are standard to most airplanes. The altimeter for altitude, airspeed for general forward speed in knots, and vertical air speed for how fast the plane is moving up or down.

At supersonic speeds and very high altitudes, outside air conditions, and supersonic airflow around the plane's exterior components affects instrument accuracy. As such, SR-71 pilots relied on the triple display indicator at speed. There's the KEAS indicator at the top for knots equivalent airspeed, which takes into account air compressibility at high altitude for an adjusted speed calculation.

For reference, there could be up to 100 knots difference between the normal airspeed indicator and this adjusted reading. Altitude is beneath that, and Mach at the bottom. Down and to the right, there are fuel flow gauges measured in thousands of pounds per hour.

Oil pressure gauges are nearby. There are gauges for hydraulic pressure in various systems. Above that, a grouping of instruments related to exhaust, including exhaust nozzle position indicators and exhaust temperature.

Normal running temperature is 800 degrees Fahrenheit (426. 6 C), and can be manually adjusted or "trimmed" by the pilot. There are fire warning lights nearby, and tachometers to measure engine rotation speed.

Idle is about 3900 RPM, while cruise is around 7,100 RPM. That's not much difference in engine rotation speed for all the action happening in that part of the plane. There's an elapsed time gauge which is a sort of stopwatch used, for example, in monitoring expected travel time between points.

Rarely used, but a government requirement. Moving leftward, there's the angle of attack indicator to track the plane's angle relative to its direction of travel. You'll recall from earlier, the plane is designed to sit at about 6 degrees angle of attack at cruise.

There are gauges, switches, and lights related to the previously shown inlets, spikes, and engines. For most of the flight, the inlets are automatically controlled by onboard computers, but the pilot can take manual control if needed. There are left and right inlet unstart warning lights, with restart switches at the bottom left.

There's a spike position gauge, with two indicators, one for each side. and position switches. Compressor inlet temperature, and pressure gauges to monitor conditions at the compressor face or front of the J58 jet engine.

with a pair of switches for air bypass control in this area. There's a stick pusher/shaker switch to the left. When turned on, the stick will shake if the pilot is approaching angle of attack limits, and forcefully push the stick forward if the pilot ignores the shaking.

The RSO bailout switch is used to request bailout, since the RSO (the backseat officer) should go first in emergency bailout conditions, to avoid safety concerns with opening canopies and so on. The RSO ejected light indicates if the RSO has actually ejected. These are also failsafes if the communication system between officers isn't working.

The drag chute pull handle is up and to the left. At the bottom, there are indicator gauges for pitch, roll, and yaw trim levels. The roll trim switch is at the left side of the cockpit.

A combined pitch and yaw trim switch is located on the flight stick, with left-to-right for yaw and up-and-down for pitch. While we're at the stick, let's review other controls here. There's a button to switch the pilot's microphone between internal or external communication.

The dual purpose button to the right either activates control stick command so the pilot can use the stick during autopilot, or it can activate nosewheel steering when on the ground. A button towards the front turns on the rain removal system. And a multi-purpose trigger at the front can control things like disconnecting air refueling components, interrupting pitch or yaw trim, and more.

While in flight, the rudder pedals at each side control rudder angle when pressed inwards from the bottom. Moving feet up to rotate the pedals controls wheel braking for each side while on the ground. Moving now to the right or starboard side of the cockpit, there are instruments related to fuel management.

Balancing the massive fuel load front to back greatly affects performance, since the plane, again, is designed to sit at a particular angle. There's the main fuel level gauge in pounds. Beneath that, the center of gravity indicator.

The fuel system draws from forward tanks and works backwards, so the center of gravity will move aft as fuel is consumed. At speed, this center of gravity has shifted 25% towards the back. There's a fuel forward transfer switch that moves fuel back into forward tanks when switched on.

And a corresponding fuel aft transfer switch, which moves fuel rearward, and must be held down to operate. There's a fuel tank pressure gauge at the bottom, and gauges to measure nitrogen quantity in various tanks, which is used for inerting, as we saw in the fuel system explanation. There's a fuel dump switch to quickly dump thousands of pounds of fuel, for example to drop weight in an emergency situation.

Emergency fuel shutoff switches are nearby. Now let's head over to the left or port side of the cockpit. There's a grouping of dials for environmental controls, such as cockpit temperature, face heat and suit heat, which control heating in the pilot's helmet and suit, and a nearby temperature gauge with a switch to select which system it should display.

For equipment survival, cockpit temps shouldn't exceed 140 deg. F (60 C). Which I'm sure the crew would appreciate as well.

Near the bottom there's a cabin altitude gauge. Crew could choose cabin pressurization equivalent to 10,000 or 26,000 ft. (3048 - 7924.

8 m) And a liquid oxygen level indicator beneath. Liquid oxygen is converted to gas and pumped into crew's helmets for breathing. The landing gear lever is nearby, with associated indicator lights, switches, and so on.

As we pivot all the way to the left side wall, we see the dual throttle levers. There's a button here to toggle the pilot's microphone. And a switch beneath that to manually initiate the inlet spike restart sequence Each throttle channel has a TEB counter to track how many shots of TEB are used, from a starting total of 16 shots per side.

For example, the throttles move forward up to a limit which corresponds to normal engine power. The pilot must lift throttles up over this detent to engage afterburners. Doing so fires a shot of TEB to start the afterburners, and the counters tick down each time this happens.

Afterburner power is controllable from min to max along the stick travel. There's an oxygen settings control panel behind that. A nearby pull handle will jettison the canopy.

Other panels here include a radio panel, standby oxygen panel, a panel for various lights such as landing gear lights and more. Controls for the map projector are found towards the front of this panel area. Corresponding banks of controls on the starboard side handle things like internal comms system, computer navigation aids for flying, landing and takeoff, autopilot, and more.

The rear cockpit echoes many of the same gauges, switches, and indicators, with some crucial additions. There's a view sight monitor which lets the RSO see directly beneath the plane, with magnification settings, and more. A radar display sits beneath that, and a large map projector pane.

There's a control panel for the astroinertial navigation device, which we'll cover in a bit. There's a panel with controls and indicators for reconnaissance equipment. Controls at the left side include a DEF panel to engage onboard defensive systems, which could counter any threats to the plane, from things like surface to air missiles, air to air missiles, hostile fighter intercept attempts, and so on.

There are also radio and intercom controls in this area. As we move away from the controls, we can take in other items in these cockpits. The RSO has retractable sun shades.

The pilot has a positionable sun visor with wings. Sun glare at altitude could make instrument visibility almost impossible if not blocked. Both cockpits have small mirrors to help crew see themselves, due to the difficulty of some actions in their bulky flight suits in confined quarters.

The pilot has a retractable periscope to view the plane looking aft for things like engine fires, contrailing, fuel dumping, and to check rudder position. Windows have inner and outer panes with an air gap. Glass at the outside reached temperatures of 400-500 degrees Fahrenheit (204 - 260 C) at cruise, with the interior pane's surface in the 250 degree (121 C) range.

The cockpit had to have air pumped in at -40 to keep interior temps at a comfortable 60 degrees (15. 5 C) for crew, who wore their own climate controlled flight suits. The suits themselves have various critical layers, starting with a thin nylon comfort layer against the skin, followed by an inflatable rubber bladder layer for added warmth against cold air or water in the event of emergency exit from the cockpit.

A fishnet type layer helps the suit keep its proper shape when inflated, and the iconic orange outer layer which is fire resistant up to 800 F (426. 7 C). There are metal rings for glove and helmet attach points.

There are connections for climate and breathing air. There are easily accessible leg zipper pockets, and velcro pads just above knees for sticking important documents. The helmet has a face shield with a sun visor, and a feeding port for squeezing food out of tubes.

There's a neoprene seal around the face to allow pressurization to sea level for comfortable breathing, where the rest of the suit matched cockpit pressure levels. The seat has a parachute in the head rest, and is anchored to a support rack upon which it slides during the ejection process. There are cables at the bottom for attachment to metal brackets at the heel of each boot.

These cables pull the pilot's feet tight to the seat frame during ejection to avoid striking limbs as the seat blasts out of the cockpit. Equipment The nose and side bays at the front of the plane have components for both airplane functionality and mission-specific objectives. I'll show you the zoomed in individual units, and then we'll zoom out so you can see their range and capabilities from 80,000 ft (24,384 m) down to the earth's surface.

The pitot mast is a thin tube with various probes which feeds air pressure data to onboard computers and instruments for things like airspeed, angle of attack, and more. The entire nose is interchangeable and can be swapped out between flights to suit mission objectives. There are three noses, two with different radar types, and an optical bar camera which I've featured here.

The optical bar camera had film reels that carried 10,500 ft (3,200 m) of 5-inch (12. 7 cm) wide film. For comparison, a normal 90 minute movie would use 8,100 feet (2,468.

8 m) of 35mm film (~1. 38 in). It could also film in stereo vision to help identify objectives easier.

Moving aft, there are liquid oxygen supply bottles. There are bays which house components for the SR-71's defensive systems. Further aft, there's a bay with radar recording equipment.

The Blackbird's unusual speed and altitude tended to activate hostile radar and missile systems along its flight path. These signals could be captured and analyzed to better understand their capabilities. The bays behind that hold technical objective cameras for more detailed photography of smaller, specific areas.

Just behind the rear cockpit, there's the Astro Inertial Navigation System (ANS) to precisely monitor airplane location. It would track three star groups within 30 seconds after leaving the hangar, no matter the time of day. The SR-71's location could be pinpointed to within 300 feet (91 m) anywhere in the world, even at Mach speeds.

This was well before the existence of GPS satellites. Also in these bays and compartments there are batteries, radio equipment, antennas, and computers that run or assist other components related to mission goals, airplane function, and more. And here's a zoomed out diagram to show you what each component sees.

The optical bar camera can continuously photograph an 82 mile (131 km) wide by 2. 3 miles (3. 7 km) long patch.

Radar can monitor an 11 mile (17. 7 km) area from 23 to 115 miles (37 - 185 km) from the flight path. Signal (radar etc.

) recorders can see from horizon to horizon. Technical objective cameras locate and photograph hundreds of targets to within 6 inches (15 cm) of resolution within a 16 mile range (26 km) side to side. Perhaps what makes the SR-71 so special is its rarity.

To have the right people and talents come together, with proper funding, and be allowed to flex their talents fully is apparently a very rare thing indeed, and often results in legends that persist. Hey everyone, Jake here, creator of Animagraffs. First of all thanks for being on the channel and enjoying my work!

This project was AWESOME to create and I'm going to be releasing a behind the scenes video shortly after the release of this one, detailing everything that went into making this project. From the research that I had to find and dig deep to get, to crafting the model, and doing the materials, and rendering, and the rigs -- so, building the moving mechanical objects. The items in these projects, many of them actually work how they would in real life!

These are real recreations and I want to show you how I do it and bring you into the magic and The Madness of making Animagraffs. I'll be entertaining and I might even tell a few light jokes here and there so something to look forward to. Anyway [Music] Later!

Related Videos

39:57

The Pratt & Whitney J58 - The Engine of th...

Air Zoo

150,975 views

25:04

The Insane Engineering of the F-35B

Real Engineering

8,993,823 views

10:29

The History of Truk Naval Base

Shipwreck Sunday

11,709 views

30:52

How a World War Two Submarine Works

Animagraffs

6,278,633 views

53:58

Decoding the Universe: Quantum | Full Docu...

NOVA PBS Official

2,458,794 views

32:29

The End of The International Space Station

The B1M

241,665 views

45:14

Modern Marvels: Jet Engines (S5, E6) | Ful...

HISTORY

919,358 views

25:27

How an 18th Century Sailing Warship Works ...

Animagraffs

12,909,645 views

28:08

The Insane Engineering of the Space Shuttle

Real Engineering

1,398,103 views

1:10:57

Author Brian Shul on piloting the SR-71

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

1,583,023 views

33:45

Why It Was Almost Impossible to Make the B...

Veritasium

31,860,484 views

55:30

How a Helicopter Works (Bell 407)

Animagraffs

2,602,915 views

3:22:17

3 Hours Of WW2 Facts To Fall Asleep To

Timeline - World History Documentaries

6,177,222 views

31:32

Flying the U-2 Spy Plane 70,000 Feet to th...

Sam Eckholm

4,598,048 views

57:24

How Airplane Wings REALLY Generate Lift

Math and Science

702,782 views

28:31

The Real Reason The Boeing Starliner Failed

The Space Race

2,502,760 views

31:30

The Insane Engineering of the X-15

Real Engineering

8,193,388 views

20:04

The Dumbest Drivers Ever

Daily Dose Of Internet

2,985,080 views

1:10:57

LLESA Author Series | "Sled Driver: Flyin...

Inside Livermore Lab

2,081,205 views

1:17:50

How The Space Shuttle Worked | Full Docume...

Real Engineering

2,222,679 views