Mental or Inner Restlessness and ADHD

17.29k views2648 WordsCopy TextShare

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science

00:00 Introduction

00:56 Definition of this symptom

02:23 History of it in ADHD and relationship to ...

Video Transcript:

Greetings, everyone, and happy holidays to you! As you can see, we've got Santa Claus in the background making a guest appearance on my show, and I'm also in my gym clothes because right after I record this, I've got to get my butt on my elliptical trainer so I can try to stay healthy long enough to keep this channel going. So, again, happy holidays!

Today, I want to talk to you about a subject that was suggested to me by a subscriber from Estonia, and that is Anna. Anna, if you're listening, thanks so much for this idea because after I delved into it further, I found just how disruptive this symptom has, or tends to be. So, let's have a look at this PowerPoint presentation I put together for you.

We're going to go through this pretty quickly, although to some extent, it's kind of a deep dive into this problem and its origins. But I'll try to be as quick as I can because I know you guys don't like really long videos. So, we're going to talk about mental or inner restlessness and its relationship to ADHD.

Now, a little bit of background for you: restlessness is defined as that quality of being unwilling or unable to stay still or to be quiet and calm. It perhaps arises because someone is worried or bored. Side effects can include excessive and task-irrelevant movements, impatience, as well as irritability.

So, all of that comes from various dictionaries. As you can see, this definition suggests that it might be associated not only with ADHD out of boredom, perhaps, but also with anxiety and other disorders linked to worrying. Let's move on.

However, when this symptom is mental in form, it is often associated with an unrest of the mind, and as many patients with adult ADHD have described, it involves difficulties with stopping one's thinking, including when trying to fall asleep, having too many thoughts coming to you all at once—kind of a problem with disinhibition there—and thoughts that are off-task. They're not really relevant to what the individual is trying to do, and as a result, they can be very distracting. As you will see in a moment, this suggests that this symptom of mental or inner restlessness might also be associated with mind-wandering.

Now, in the history of ADHD, this symptom was first described back in 1798 in a medical textbook written by Alexander Crichton, a Scottish physician. In this chapter, he was describing disorders of attention, one of which resembles ADHD in adults, but he was the first one to talk about this kind of mental restlessness in individuals. Often, this symptom in children is one that is not widely discussed because it’s probably not there.

By that, I mean that the symptom is an outward motor restlessness, hyperactivity, and even excessive talking, which is hyperactivity of speech—all of which is apparent. But we don't hear parents and children complaining about an inner or mental restlessness in a child with ADHD, and I'll explain why that might be the case in a moment. Because the inner life of a child is not quite so rich as that of adulthood, nevertheless, it is associated even in children—that is, this outward restlessness—with impatience and irritability.

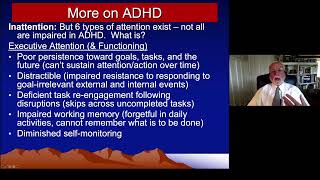

Yet the inner version of restlessness seems to be a classic symptom of adult ADHD. So, why is it that in children it's overt physical hyperactivity and excess of speech, while by adulthood it becomes more covert, private, inner, or mental in nature? We're going to talk about why that might be the case shortly, but it appears that mental restlessness, like physical restlessness and hyperactivity in children, is probably more closely related to the inhibitory symptom dimension of ADHD than it is to the inattention dimension.

Although eventually, it will be related because of that issue of mental distractibility that is likely associated with this inner restlessness. Now, Lisa Wyatt was among the first to develop a rating scale to assess this aspect of adult ADHD, and she showed in college students that they rated themselves as having significantly higher levels of this symptom if they had ADHD in comparison to college students who were more neurotypical. So, Lisa was the first to say, “Hey, we need to explore this symptom in much more detail in our research.

” In order to do that, she went on to develop a systematic, validated rating scale of ADHD inner restlessness. So, if you're looking for a way to measure this in your own research or in your clinical practice, Lisa has a scale that you can locate using Google Scholar to search the journals. Okay, enough of that.

Now, this mental restlessness, she found, was also related to decisions to maximize immediate rewards—that is, to maximize the outcomes of decision-making. She also found that it was linked to feelings of regret, particularly regret regarding these rather hastily put-together decisions to try to maximize immediate rewards or stimulation. So, people often had regrets after the fact in these decision-making activities that Lisa was studying.

This might explain why inner restlessness is eventually associated with anxiety and depression in ADHD over time; at least, we think it might be, but that remains open to question. Now, a little more background for you: this is not the classic symptom that we see in psychosis or mania, so don't necessarily confuse the two. They also complain of a mental restlessness, but theirs involves a pressuring of speech—this rapid talking to the point where words are tripping over each other.

Although we see excessive talking in adults with ADHD, it's not pressured in that sense—the need to sort of get it out of the head. It's also not associated with the flight of ideas that we see in mania and psychosis, which is not only ideas that are skipping around. Across topics, but are rather bizarre in their content, the content of adult ADHD symptoms of restlessness in their mind—such as these thoughts—really isn't necessarily bizarre; it's just skipping all over the place as a result of likely inhibitory problems in thinking.

So, don't confuse it with psychosis or mania. The symptom has been associated in the brain with dysfunctioning of the prefrontal cortex, which makes perfect sense because we know that that's one region of the brain involved in ADHD. It's probably due to the fact that this deficient functioning results in a release of the typical inhibition we have over our actions and over our minds—not just our physical behavior and our speech, but also the inhibition of mental activity so that we can focus on tasks and accomplish them effectively.

Thus, it appears to be a disinhibitory effect over both the motor and verbal areas of the brain, such as through the structure known as the striatum. Now, it might also be related to dysfunctioning in the default mode network. We know that in people with ADHD, the default mode network is not being governed by the frontal executive brain as well as it should be; so it's kind of a rogue or renegade network.

It's this network that's related to mind wandering and daydreaming, and Joe Beerman and others have found that the mind-wandering aspect of this inner or mental restlessness is very much related to the mind-wandering and default mode network aspects of neurological functioning. So, there may be some relationship here—not just to mental restlessness, but as part of that mind wandering. Now, there was a nice little paper back in 2017 by a student over, I believe, in Norway that proposed that this aspect of ADHD, and ADHD more generally, might be related to the impaired sense of time.

As you know, I've been talking about ADHD and time blindness now for more than 30 years as a major deficit in ADHD. Neelson argues that this creates a desynchrony between the individual and their social environment, so that the individual feels out of sync, out of step, and arhythmic, if you will, relative to their outer social world. This might lead to not only ADHD but also to this mental restlessness.

I happen to think that while this problem with time is definitely a central problem for ADHD, I don't think it explains all of ADHD, as Neelson has tried to do. Nevertheless, it's an entertaining idea, particularly with regard to this mental restlessness. Now, why would mental restlessness develop in ADHD?

Why would it start out as being physical in children, not mental? It's just overt hyperactivity: restless behavior, fidgeting, and so on. But it's also then associated with impatience, hostility, as well as poor emotion regulation—the irritability that some people talk about.

Why would it go from being overt to covert? I think the answer to that comes from my theory of executive functioning. So, have a look at my videos on my channel that explain this theory in more detail, but very quickly, that theory says that there are three important processes taking place across child and adolescent development where behavior goes from being external to being internal or mental in form.

First, we engage in self-directed actions. This starts at around 3 to 5 years of age when children start to talk to themselves. So, I'm going to use speech as a good example of this: Before 3 years of age, children talk to the world, but between 3 and 5, they start to talk to themselves—even when nobody's in the room.

Now, by 5 to 7, this speech has become quiet; it's whispering. Later in childhood, the outward signs of speaking disappear, and children now report having a voice in their head—a voice in the mind; inner speech. Thus, behavior goes from being externally directed to self-directed to mental, and that's all because of inhibition.

We're inhibiting the motor aspects of our behavior; we're inhibiting the spinal cord so that we can think without action. Next, in that process, these behaviors become private in form. That's the last stage of developing executive functioning, where we can now do things in our head without moving.

We can talk, we can think, we can act. For example, I can practice my golf swing, and you can't see that happening. So, there's a privatization of behavior that occurs—mainly, if not exclusively, in humans—that's occurring across development.

It creates a mental world in which we can act, think, and talk in mental form without our body engaging in those actual overt actions. Just as important as this privatization and internalization are taking place, they become more and more regulatory. They start to govern our behavior increasingly so that we can do what we think—thinking guides action.

That's also important because that is a major aspect of self-regulation. So, diagrammatically, let's have a look here at what this may tell us about inner restlessness. Here’s a diagram that shows that process in young children.

Over on the left side of my diagram, you see children are stimulus-response creatures; they're externally directed. So, events are happening, and they're reacting to those. There's nothing mental going on in the mind of someone, let's say, who's a preschooler, but as they develop, look at what's going to happen: things are going to happen to them—events—they're going to have mental reactions to these; they're going to be talking to themselves, singing to themselves, emoting to themselves, and then that's going to lead to certain actions.

This is the stage at which inner or mental representations can be used to guide external actions, but we can still see a lot of this happening overtly. So, finally, By late childhood and especially by adulthood, we can do all of this in our head. We have a form of mental simulation; we can create images, words, statements, impressions, and we can use them to guide action over time to our goals.

We have an inner life, which is why humans have an inner self and an outer self, whereas children just have the outer self. Now, can you see how this links up with how we go from overt to mental restlessness? It's because there's a delay in the development of executive functioning, so that people with ADHD are acting more overtly and outwardly.

They're talking, they're touching, they're moving, they're restless, and are doing so longer into development than typical people. But eventually, even those with ADHD do begin to internalize these actions. They go from being public to private, outward to mental; and as they go from being outward to inward, actions that hyperactivity, that restlessness, that impatience, that we were seeing in children also go from being overt to mental.

I think that is the origin of that mental restlessness. After all, if our mental life is our actions and our words in private, if you're already restless, impatient, hyperactive, and talkative by the time you're an adult, those become internal. You now have this mental form of restlessness, which can be very disruptive.

So, I think that's how we get from childhood hyperactivity and excessive talking to adults reporting on mental restlessness. In conclusion, this mental and unobservable symptom, in its very nature, will prove to be highly disruptive in day-to-day functioning, leading to impairments in multiple domains. If you would like a description of this, see my video about Trevor Noah and his ADHD, where he gives a great discussion of this kind of skipping across ideas in his mind while he's listening to a friend who's talking to him.

This may be related to the increasing development of risk for regret and demoralization, and possibly for the development of anxiety and maybe even depression in those with ADHD. After all, if your mind is difficult to control and it's leading you to make decisions that you later regret, it doesn't take long for that to have some kind of emotional aspect to it. Side effects of that kind of inner mental restlessness and decision-making: we know that the inner restlessness is just as subject, just as responsive, to treatment with ADHD medications as the outward hyperactivity and talkativeness are in ADHD children.

So, good thing this is really a symptom of ADHD, and it is a symptom that can be managed with ADHD medications. It's also something that can be further managed through the use of cognitive behavior therapy programs that target executive deficits in adults with ADHD. Programs such as those by Mary Canto, Russ Ramsey, Steve Saffron, and more recently, those by Laura Naous and her colleagues for college students as well.

You can find all of these by Googling them, or just go to Amazon or any major bookseller and you can type in these authors' names, and you'll find their books. It might be possible that mindfulness-based practices could be of some help in managing this mental restlessness. I don't know; I'll have to take a look at John Mitchell and Lydia Xy's book on that subject, "Mindfulness-Based Practices for Adults with ADHD.

" But I would think that that kind of mindfulness might help to slow down this mental restlessness, though I would think that just as with CBT, or cognitive behavior therapy, they would not be as effective as the medications would be. But put them all together, and you probably have a good treatment package for managing not just ADHD symptoms generally, but this problem with mental restlessness. Well, hey everybody!

Thanks for joining me for this topic, and I want to thank Anna again for suggesting a deeper dive into internal restlessness in adult ADHD. As I said earlier, happy holidays to you; I hope you enjoy the month. I certainly will!

I do like Christmas, and I'll be getting on with my Christmas shopping right after I finish exercising today. But as always, everyone, live well, be well, and please take care.

Related Videos

1:30:38

Adult ADHD What You Need to Know

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

177,906 views

22:01

Sleep Problems & ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

41,072 views

1:45:53

ADHD, EF, and Self Regulation

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

23,932 views

13:26

Anxiety and ADHD - How Are They Related?

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

20,012 views

22:02

Why Dr Gabor Mate' is Worse Than Wrong Ab...

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

165,957 views

28:48

ADHD Aha! | ADHD and the myth of laziness ...

Understood

23,060 views

17:38

Loneliness & ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

50,657 views

29:30

I found out I have ADHD.

Laura Try

13,591 views

13:49

ADHD, IQ, and Giftedness

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

263,563 views

21:31

Do I regret starting ADHD medication? Refl...

Rachel Walker

71,910 views

24:51

Screening for ADHD in Yourself or Your Child

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

23,688 views

11:14

Trevor Noah Brilliantly Describes His ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

145,292 views

13:36

Should You Be Assessed For ADHD? Psychiatr...

Harley Therapy - Psychotherapy & Counselling

1,719,775 views

2:39:28

ADHD Overview

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

34,715 views

2:02:12

Adderall, Stimulants & Modafinil for ADHD:...

Andrew Huberman

1,333,516 views

19:36

ADHD: A Left-handed Brain

No Boilerplate

123,647 views

14:44

Owning Your ADHD

Russell Barkley, PhD - Dedicated to ADHD Science+

28,338 views

13:41

The myth of ADHD laziness | Tips from an A...

Understood

2,679 views

2:03:06

Autism Misdiagnosed As Bipolar Disorder

Thomas Henley

17,688 views

20:45

If You HEAR THIS, That's A Narcissist Tryi...

Dhru Purohit

929,475 views