Fractals are typically not self-similar

4.09M views3402 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

An explanation of fractal dimension.

Help fund future projects: https://www.patreon.com/3blue1brown

...

Video Transcript:

Who doesn't like fractals? They're a beautiful blend of simplicity and complexity, often including these infinitely repeating patterns. Programmers in particular tend to be especially fond of them, because it takes a shockingly small amount of code to produce images that are way more intricate than any human hand ever could hope to draw.

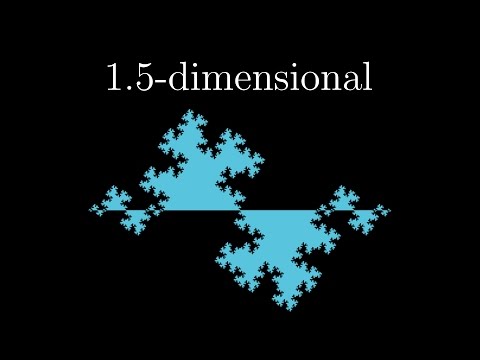

But a lot of people don't actually know the definition of a fractal, at least not the one Benoit Mandelbrot, the father of fractal geometry, had in mind. A common misconception is that fractals are shapes that are perfectly self-similar. For example, this snowflake-looking shape right here, called the Von Koch snowflake, consists of three different segments, and each one of these is perfectly self-similar, in that when you zoom in on it, you get a perfectly identical copy of the original.

Likewise, the famous Sierpinski triangle consists of three smaller identical copies of itself. And don't get me wrong, self-similar shapes are definitely beautiful, and they're a good toy model for what fractals really are. But Mandelbrot had a much broader conception in mind, one motivated not by beauty, but more by a pragmatic desire to model nature in a way that actually captures roughness.

In some ways, fractal geometry is a rebellion against calculus, whose central assumption is that things tend to look smooth if you zoom in far enough. But Mandelbrot saw this as overly idealized, or at least needlessly idealized, resulting in models that neglect the finer details of the thing they're actually modeling, which can matter. What he observed is that self-similar shapes give a basis for modeling the regularity in some forms of roughness, but the popular perception that fractals only include perfectly self-similar shapes is another over-idealization, one that ironically goes against the pragmatic spirit of fractal geometry's origins.

The real definition of fractals has to do with this idea of fractal dimension, the main topic of this video. You see, there is a sense, a certain way to define the word dimension, in which the Sierpinski triangle is approximately 1. 585D, that the Von Koch curve is approximately 1.

262D. The coastline of Britain turns out to be around 1. 21D, and in general it's possible to have shapes whose dimension is any positive real number, not just whole numbers.

I think when I first heard someone reference fractional dimension like this, I just thought it was nonsense, right? I mean, mathematicians are clearly just making stuff up. Dimension is something that usually only makes sense for natural numbers, right?

A line is one-dimensional, a plane that's two-dimensional, the space that we live in that's three-dimensional, and so on. And in fact, any linear algebra student who just learned the formal definition of dimension in that context would agree, it only makes sense for counting numbers. And of course, the idea of fractal dimension is just made up.

I mean, this is math, everything's made up. But the question is whether or not it turns out to be a useful construct for modeling the world. And I think you'll agree, once you learn how fractal dimension is defined, it's something that you start seeing almost everywhere that you look.

It actually helps to start the discussion here by only looking at perfectly self-similar shapes. In fact, I'm going to start with four shapes, the first three of which aren't even fractals. A line, a square, a cube, and a Sierpinski triangle.

All of these shapes are self-similar. A line can be broken up into two smaller lines, each of which is a perfect copy of the original, just scaled down by a half. A square can be broken down into four smaller squares, each of which is a perfect copy of the original, just scaled down by a half.

Likewise, a cube can be broken down into eight smaller cubes, again, each one is a scaled down version by one half. And the core characteristic of the Sierpinski triangle is that it's made of three smaller copies of itself, and the length of the side of one of those smaller copies is one half the side length of the original triangle. Now, it's fun to compare how we measure these things.

We'd say that the smaller line is one half the length of the original line, the smaller square is one quarter the area of the original square, the smaller cube is one eighth the volume of the original cube, and that smaller Sierpinski triangle? Well, we'll talk about how to measure that in just a moment. What I want is a word that generalizes the idea of length, area, and volume, but that I can apply to all of those shapes and more.

And typically in math, the word that you'd use for this is measure, but I think it might be more intuitive to talk about mass, as in, imagine that each of these shapes is made out of metal, a thin wire, a flat sheet, a solid cube, and some kind of Sierpinski mesh. Fractal dimension has everything to do with understanding how the mass of these shapes changes as you scale them. The benefit of starting the discussion with self-similar shapes is that it gives us a nice clear-cut way to compare masses.

When you scale down that line by one half, the mass is also scaled down by one half, which you can viscerally see because it takes two copies of that smaller one to form the whole. When you scale down a square by one half, its mass is scaled down by one fourth, where again you can see this by piecing together four of the smaller copies to get the original. Likewise, when you scale down that cube by one half, the mass is scaled down by one eighth, or one half cubed, because it takes eight copies of that smaller cube to rebuild the original.

And when you scale down the Sierpinski triangle by a factor of a half, wouldn't you agree that it makes sense to say that its mass goes down by a factor of one third? I mean, it takes exactly three of those smaller ones to form the original. But notice that for the line, the square, and the cube, the factor by which the mass changed is this nice clean integer power of one half.

In fact, that exponent is the dimension of each shape. And what's more, you could say that what it means for a shape to be, for example, two-dimensional, what puts the two in two-dimensional, is that when you scale it by some factor, its mass is scaled by that factor raised to the second power. And maybe what it means for a shape to be three-dimensional is that when you scale it by some factor, the mass is scaled by the third power of that factor.

So if this is our conception of dimension, what should the dimensionality of a Sierpinski triangle be? You'd want to say that when you scale it down by a factor of one half, its mass goes down by one half to the power of whatever its dimension is. And because it's self-similar, we know that we want its mass to go down by a factor of one third.

So what's the number d such that raising one half to the power of d gives you one third? Well, that's the same as asking two to the what equals three, the quintessential type of question that logarithms are meant to answer. And when you go and plug in log base two of three to a calculator, what you'll find is that it's about 1.

585. So in this way, the Sierpinski triangle is not one-dimensional, even though you could define a curve that passes through all its points, and nor is it two-dimensional, even though it lives in the plane. Instead, it's 1.

585 dimensional. And if you want to describe its mass, neither length nor area seem like the fitting notions. If you tried, its length would turn out to be infinite, and its area would turn out to be zero.

Instead, what you want is whatever the 1. 585 dimensional analog of length is. Here, let's look at another self-similar fractal, the von Koch curve.

This one is composed of four smaller identical copies of itself, each of which is a copy of the original scaled down by one third. So the scaling factor is one third, and the mass has gone down by a factor of one fourth. So that means the dimension should be some number D, so that when we raise one third to the power of D, it gives us one fourth.

Well, that's the same as saying three to the what equals four, so you can go and plug into a calculator log base three of four, and that comes out to be around 1. 262. So in a sense, the von Koch curve is a 1.

262 dimensional shape. Here's another fun one. This is kind of the right angled version of the Koch curve.

It's built up of eight scaled down copies of itself, where the scaling factor here is one fourth. So if you want to know its dimension, it should be some number D, such that one fourth to the power of D equals one eighth, the factor by which the mass just decreased. And in this case, the value we want is log base four of eight, and that's exactly three halves.

So evidently, this fractal is precisely 1. 5 dimensional. Does that kind of make sense?

It's weird, but it's all just about scaling and comparing masses while you scale. And what I've described so far, everything up to this point is what you might call self-similarity dimension. It does a good job making the idea of fractional dimension seem at least somewhat reasonable, but there's a problem.

It's not really a general notion. I mean, when we were reasoning about how a mass's shape should change, it relied on the self-similarity of the shapes, that you could build them up from smaller copies of themselves. But that seems unnecessarily restrictive.

After all, most two-dimensional shapes are not at all self-similar. Consider the disk, the interior of a circle. We know that's two-dimensional, and you could say that this is because when you scale it up by a factor of two, its mass, proportional to the area, gets scaled by the square of that factor, in this case four.

But it's not like there's some way to piece together four copies of that smaller circle to rebuild the original. So how do we know that that bigger disk is exactly four times the mass of the original? Answering that requires a way to make this idea of mass a little more mathematically rigorous, since we're not dealing with physical objects made of matter, are we?

We're dealing with purely geometric ones living in an abstract space. And there's a couple ways to think about this, but here's a common one. Cover the plane with a grid, and highlight all of the grid squares that are touching the disk, and now count how many there are.

In the back of our minds, we already know that a disk is two-dimensional, and the number of grid squares that it touches should be proportional to its area. A clever way to verify this empirically is to scale up that disk by some factor, like two, and count how many grid squares touch this new scaled-up version. What you should find is that that number has increased approximately in proportion to the square of our scaling factor, which in this case means about four times as many boxes.

Well, admittedly what's on the screen here might not look that convincing, but it's just because the grid is really coarse. If instead you took a much finer grid, one that more tightly captures the intent we're going for here by measuring the size of the circle, that relationship of quadrupling the number of boxes touched when you scale the disk by a factor of two should shine through more clearly. I'll admit though that when I was animating this, I was surprised by just how slowly this value converges to four.

Here's one example. For larger and larger scaling values, which is actually equivalent to just looking at a finer grid, that data is going to more perfectly fit that parabola. Now getting back to fractals, let's play this game with the Sierpinski triangle, counting how many boxes are touching points in that shape.

How would you imagine that number compares to scaling up the triangle by a factor of two and counting the new number of boxes touched? Well, the proportion of boxes touched by the big one to the number of boxes touched by the small one should be about three. After all, that bigger version is just built up of three copies of the smaller version.

You could also think about this as two raised to the dimension of the fractal, which we just saw is about 1. 585. And so if you were to go and plot the scaling factor in this case against the number of boxes touched by the Sierpinski triangle, the data would closely fit a curve with the shape of y equals x to the power 1.

585, just multiplied by some proportionality constant. But importantly, the whole reason that I'm talking about this is that we can play the same game with non-self-similar shapes that still have some kind of roughness. And the classic example here is the coastline of Britain.

If you plop that coastline into the plane and count how many boxes are touching it, and then scale it by some amount, and count how many boxes are touching that new scaled version, what you'd find is that the number of boxes touching the coastline increases approximately in proportion to the scaling factor raised to the power of 1. 21. Here, it's kind of fun to think about how you would actually compute that number empirically.

As in, imagine I give you some shape, and you're a savvy programmer. How would you find this number? So what I'm saying here is that if you scale this shape by some factor, which I'll call S, the number of boxes touching that shape should equal some constant multiplied by that scaling factor raised to whatever the dimension is, the value that we're looking for.

Now, if you have some data plot that closely fits a curve that looks like the input raised to some power, it can be hard to see exactly what that power should be. So a common trick is to take the logarithm of both sides. That way, the dimension is going to drop down from the exponent, and we'll have a nice clean linear relationship.

What this suggests is that if you were to plot the log of the scaling factor against the log of the number of boxes touching the coastline, the relationship should look like a line, and that line should have a slope equal to the dimension. So what that means is that if you tried out a whole bunch of scaling factors, counted the number of boxes touching the coast in each instant, and then plotted the points on the log-log plot, you could then do some kind of linear regression to find the best fit line to your data set, and when you look at the slope of that line, that tells you the empirical measurement for the dimension of what you're examining. I just think that makes this idea of fractal dimension so much more real and visceral compared to abstract, artificially perfect shapes.

And once you're comfortable thinking about dimension like this, you, my friend, have become ready to hear the definition of a fractal. Essentially, fractals are shapes whose dimension is not an integer, but instead some fractional amount. What's cool about that is that it's a quantitative way to say that they're shapes that are rough, and that they stay rough even as you zoom in.

Technically, there's a slightly more accurate definition, and I've included it in the video description, but this idea here of a non-integer dimension almost entirely captures the idea of roughness that we're going for. There is one nuance though that I haven't brought up yet, but it's worth pointing out, which is that this dimension, at least as I've described it so far using the box counting method, can sometimes change based on how far zoomed in you are. For example, here's a shape sitting in three dimensions which at a distance looks like a line.

In 3D, by the way, when you do a box counting you have a 3D grid full of little cubes instead of little squares, but it works the same way. At this scale, where the shape's thickness is smaller than the size of the boxes, it looks one-dimensional, meaning the number of boxes it touches is proportional to its length. But when you scale it up, it starts behaving a lot more like a tube, touching the boxes on the surface of that tube, and so it'll look two-dimensional, with the number of boxes touched being proportional to the square of the scaling factor.

But it's not really a tube, it's made of these rapidly winding little curves, so once you scale it up even more, to the point where the boxes can pick up on the details of those curves, it looks one-dimensional again, with the number of boxes touched scaling directly in proportion to the scaling constant. So actually assigning a number to a shape for its dimension can be tricky, and it leaves room for differing definitions and differing conventions. In a pure math setting, there are indeed numerous definitions for dimension, but all of them focus on what the limit of this dimension is at closer and closer zoom levels.

You can think of that in terms of the plot as the limit of this slope as you move farther and farther to the right. So for a purely geometric shape to be a genuine fractal, it has to continue looking rough, even as you zoom in infinitely far. But in a more applied setting, like looking at the coastline of Britain, it doesn't really make sense to talk about the limit as you zoom in more and more.

I mean, at some point you'd just be hitting atoms. Instead what you do is you look at a sufficiently wide range of scales from very zoomed out up to very zoomed in, and compute the dimension at each one. And in this more applied setting, a shape is typically considered to be a fractal only when the measured dimension stays approximately constant even across multiple different scales.

For example, the coastline of Britain doesn't just look 1. 21 dimensional at a distance. Even if you zoom in by a factor of a thousand, the level of roughness is still around 1.

21. That right there is the sense in which many shapes from nature actually are self-similar, albeit not perfect self-similarity. Perfectly self-similar shapes do play an important role in fractal geometry.

What they give us are simple to describe, low-information examples of this phenomenon of roughness, roughness that persists at many different scales and at arbitrarily close scales. And that's important, it gives us the primitive tools for modeling these fractal phenomena. But I think it's also important not to view them as the prototypical example of fractals, since fractals in general actually have a lot more character to them.

I really do think that this is one of those ideas where once you learn it, it makes you start looking at the world completely differently. What this number is, what this fractional dimension gives us is a quantitative way to describe roughness. For example, the coastline of Norway is about 1.

52 dimensional, which is a numerical way to communicate the fact that it's way more jaggedy than Britain's coastline. The surface of a calm ocean might have a fractal dimension only barely above 2, while a stormy one might have a dimension closer to 2. 3.

In fact, fractal dimension doesn't just arise frequently in nature, it seems to be the core differentiator between objects that arise naturally and those that are just man-made.

Related Videos

26:06

Newton’s fractal (which Newton knew nothin...

3Blue1Brown

2,889,684 views

29:42

Why 4d geometry makes me sad

3Blue1Brown

1,058,576 views

12:07

Space filling curves filling with water

Steve Mould

8,268,354 views

32:44

The Simple Math Problem That Revolutionize...

Veritasium

7,163,707 views

33:06

Something Strange Happens When You Keep Sq...

Veritasium

7,481,164 views

15:42

Divergence and curl: The language of Maxw...

3Blue1Brown

4,403,393 views

16:13

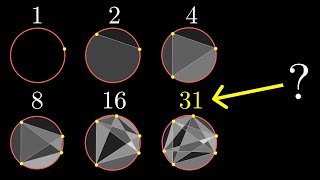

This pattern breaks, but for a good reason...

3Blue1Brown

2,308,281 views

9:27

Hexagons are the Bestagons

CGP Grey

15,075,685 views

28:47

there are 48 regular polyhedra

jan Misali

2,965,071 views

27:07

Thinking outside the 10-dimensional box

3Blue1Brown

3,064,243 views

21:58

Group theory, abstraction, and the 196,883...

3Blue1Brown

3,146,909 views

13:33

Black Hole's Evil Twin - Gravastars Explained

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell

3,425,462 views

27:11

You're Probably Wrong About Rainbows

Veritasium

4,443,158 views

26:19

Perfect Shapes in Higher Dimensions - Numb...

Numberphile

5,302,761 views

15:30

The Mandelbrot Set

D!NG

2,056,966 views

27:36

Beyond the Mandelbrot set, an intro to hol...

3Blue1Brown

1,528,567 views

31:51

Visualizing quaternions (4d numbers) with ...

3Blue1Brown

4,779,996 views

23:46

How To Count Past Infinity

Vsauce

26,886,942 views

18:18

Hilbert's Curve: Is infinite math useful?

3Blue1Brown

2,273,161 views

16:06

The Greatest Mathematician Who Ever Lived

Newsthink

514,081 views