Cross products | Chapter 10, Essence of linear algebra

1.92M views1515 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

This covers the main geometric intuition behind the 2d and 3d cross products.

Help fund future proje...

Video Transcript:

Last video I talked about the dot product, showing both the standard introduction to the topic, as well as a deeper view of how it relates to linear transformations. I'd like to do the same thing for cross products, which also have a standard introduction, along with a deeper understanding in the light of linear transformations, but this time I'm dividing it into two separate videos. Here, I'll try to hit the main points that students are usually shown about the cross product, and in the next video I'll be showing a view which is less commonly taught, but really satisfying when you learn it.

We'll start in two dimensions. If you have two vectors, v and w, think about the parallelogram that they span out. What I mean by that is that if you take a copy of v and move its tail to the tip of w, and you take a copy of w and move its tail to the tip of v, the four vectors now on the screen enclose a certain parallelogram.

The cross product of v and w, written with the x-shaped multiplication symbol, is the area of this parallelogram. Well, almost. We also need to consider orientation.

Basically, if v is on the right of w, then v cross w is positive and equal to the area of the parallelogram. But if v is on the left of w, then the cross product is negative, namely the negative area of that parallelogram. Notice this means that order matters.

If you swapped v and w, instead taking w cross v, the cross product would become the negative of whatever it was before. The way I always remember the ordering here is that when you take the cross product of the two basis vectors in order, i-hat cross j-hat, the result should be positive. In fact, the order of your basis vectors is what defines orientation.

So since i-hat is on the right of j-hat, I remember that v cross w has to be positive whenever v is on the right of w. So for example, with the vectors shown here, I'll just tell you that the area of that parallelogram is seven. And since v is on the left of w, the cross product should be negative.

So v cross w is negative seven. But of course, you want to be able to compute this without someone telling you the area. This is where the determinant comes in.

So if you didn't see chapter five of this series, where I talk about the determinant, now would be a really good time to go take a look. Even if you did see it, but it was a while ago, I'd recommend taking another look just to make sure those ideas are fresh in your mind. For the 2D cross product, v cross w, what you do is you write the coordinates of v as the first column of a matrix, and you take the coordinates of w and make them the second column, then you just compute the determinant.

This is because a matrix whose columns represent v and w corresponds with a linear transformation that moves the basis vectors i-hat and j-hat to v and w. The determinant is all about measuring how areas change due to a transformation, and the prototypical area that we look at is the unit square resting on i-hat and j-hat. After the transformation, that square gets turned into the parallelogram that we care about.

So the determinant, which generally measures the factor by which areas are changed, gives the area of this parallelogram, since it evolved from a square that started with area one. What's more, if v is on the left of w, it means that orientation was flipped during that transformation, which is what it means for the determinant to be negative. As an example, let's say v has coordinates negative 3, 1, and w has coordinates 2, 1.

The determinant of the matrix with those coordinates as columns is negative 3 times 1 minus 2 times 1, which is negative 5. So evidently, the area of the parallelogram they define is 5, and since v is on the left of w, it should make sense that this value is negative. As with any new operation you learn, I'd recommend playing around with this notion a bit in your head, just to get kind of an intuitive feel for what the cross product is all about.

For example, you might notice that when two vectors are perpendicular, or at least close to being perpendicular, their cross product is larger than it would be if they were pointing in very similar directions, because the area of that parallelogram is larger when the sides are closer to being perpendicular. Something else you might notice is that if you were to scale up one of those vectors, perhaps multiplying v by 3, then the area of that parallelogram is also scaled up by a factor of 3. So what this means for the operation is that 3v cross w will be exactly 3 times the value of v cross w.

Now, even though all of this is a perfectly fine mathematical operation, what I just described is technically not the cross product. The true cross product is something that combines two different 3d vectors to get a new 3d vector. Just as before, we're still going to consider the parallelogram defined by the two vectors that we're crossing together, and the area of this parallelogram is still going to play a big role.

To be concrete, let's say that the area is 2. 5 for the vectors shown here. But as I said, the cross product is not a number, it's a vector.

This new vector's length will be the area of that parallelogram, which in this case is 2. 5, and the direction of that new vector is going to be perpendicular to the parallelogram. But which way, right?

I mean, there are two possible vectors with length 2. 5 that are perpendicular to a given plane. This is where the right hand rule comes in.

Point the forefinger of your right hand in the direction of v, then stick out your middle finger in the direction of w. Then, when you point up your thumb, that's the direction of the cross product. For example, let's say that v was a vector with length 2 pointing straight up in the z direction, and w is a vector with length 2 pointing in the pure y direction.

The parallelogram that they define in this simple example is actually a square, since they're perpendicular and have the same length, and the area of that square is 4. So their cross product should be a vector with length 4. Using the right hand rule, their cross product should point in the negative x direction.

So the cross product of these two vectors is negative 4 times i-hat. For more general computations, there is a formula that you could memorize if you wanted, but it's common and easier to instead remember a certain process involving the 3D determinant. Now, this process looks truly strange at first.

You write down a 3D matrix where the second and third columns contain the coordinates of v and w. But for that first column, you write the basis vectors i-hat, j-hat, and k-hat. Then you compute the determinant of this matrix.

The silliness is probably clear here. What on earth does it mean to put in a vector as the entry of a matrix? Students are often told that this is just a notational trick.

When you carry out the computations as if i-hat, j-hat, and k-hat were numbers, then you get some linear combination of those basis vectors. And the vector defined by that linear combination, students are told to just believe, is the unique vector perpendicular to v and w, whose magnitude is the area of the appropriate parallelogram, and whose direction obeys the right hand rule. And sure, in some sense this is just a notational trick, but there is a reason for doing it.

It's not just a coincidence that the determinant is once again important. And putting the basis vectors in those slots is not just a random thing to do. To understand where all of this comes from, it helps to use the idea of duality that I introduced in the last video.

This concept is a little bit heavy though, so I'm putting it in a separate follow-on video for any of you who are curious to learn more. Arguably, it falls outside the essence of linear algebra. The important part here is to know what that cross product vector geometrically represents.

So if you want to skip that next video, feel free. But for those of you who are willing to go a bit deeper, and who are curious about the connection between this computation and the underlying geometry, the ideas that I'll talk about in the next video are just a really elegant piece of math.

Related Videos

13:10

Cross products in the light of linear tran...

3Blue1Brown

1,259,232 views

14:12

Dot products and duality | Chapter 9, Esse...

3Blue1Brown

2,607,360 views

8:10

ALL of calculus 3 in 8 minutes.

gregorian calendar

1,249,314 views

24:26

The Beauty of Bézier Curves

Freya Holmér

2,047,474 views

12:21

What's a Tensor?

Dan Fleisch

3,706,107 views

10:03

The determinant | Chapter 6, Essence of li...

3Blue1Brown

3,919,555 views

31:33

The Oldest Unsolved Problem in Math

Veritasium

12,128,515 views

17:16

Eigenvectors and eigenvalues | Chapter 14,...

3Blue1Brown

4,989,563 views

50:03

VECTORS Top 10 Must Knows (ultimate study...

JensenMath

147,077 views

17:42

Everything You Need to Know About VECTORS

FloatyMonkey

1,226,411 views

27:31

Measure the Earth’s Radius! (with this one...

Stand-up Maths

924,153 views

19:44

P vs. NP: The Biggest Puzzle in Computer S...

Quanta Magazine

879,872 views

29:42

Why 4d geometry makes me sad

3Blue1Brown

913,180 views

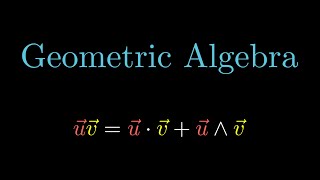

44:23

A Swift Introduction to Geometric Algebra

sudgylacmoe

879,823 views

12:51

Change of basis | Chapter 13, Essence of l...

3Blue1Brown

2,013,948 views

14:51

Visualize Different Matrices part1 | SEE M...

Visual Kernel

72,626 views

13:14

Aristotle's Wheel Paradox - To Infinity an...

Up and Atom

2,687,701 views

23:45

The applications of eigenvectors and eigen...

Zach Star

1,126,315 views

4:08

Cross Product and Dot Product: Visual expl...

Physics Videos by Eugene Khutoryansky

1,002,100 views