Why π is in the normal distribution (beyond integral tricks)

1.59M views4959 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

Where's the circle? And how does it relate to where e^(-x^2) comes from?

Help fund future projects: ...

Video Transcript:

You may have heard the phrase, the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences. This was the title of a paper by the physicist Eugene Wigner, but even more fun than the title is the way that he chooses to open it. The paper begins, quote, There is a story about two friends who were classmates in high school, talking about their jobs.

One of them became a statistician and was working on population trends. They showed a reprint to their former classmate, and the reprint started, as usual, with the Gaussian distribution. And the statistician explained to the former classmate the meaning of the symbols for the actual population, the average population, and so on.

The classmate was a bit incredulous and was not quite sure whether the statistician was pulling their leg. How can you know that? was the query.

And what is this symbol over here? Oh, said the statistician, this is pi. What is that?

The ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. Well, now you're pushing the joke too far, said the classmate. Surely the population has nothing to do with the circumference of a circle.

In the paper, Wigner then goes on to talk about the more general phenomenon of concepts and pure math, seeming to find applications that extend strangely beyond what their definitions would suggest. But I would like to stay focused on this particular anecdote and the question that the statistician's friend is getting at. You see, there is a very beautiful and classic proof that explains the pi inside the formula for a normal distribution.

And despite there being a number of other really great explanations online, see some links in the description, I cannot help but indulge in the pleasure of reanimating it here. For one thing, there is a fun side note that I didn't learn until recently about how you can use this proof to derive the volumes of higher dimensional spheres. But much more importantly than that, what I really want to do is try to go beyond the classic proof.

Consider this hypothetical statistician's friend. What I want to ask is, can we find an explanation that would satisfy their disbelief? You see, they're not just asking for some pure math proof about a function that was handed down to them on high.

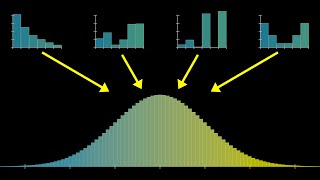

The friend's incredulity was that circles should have anything to do with population statistics. Until we fully draw that connecting line, we should consider the task incomplete. Those of you who watched the last video on the central limit theorem will have some of the backdrop here, because there we broke down the formula for a normal distribution, which is also called a Gaussian distribution.

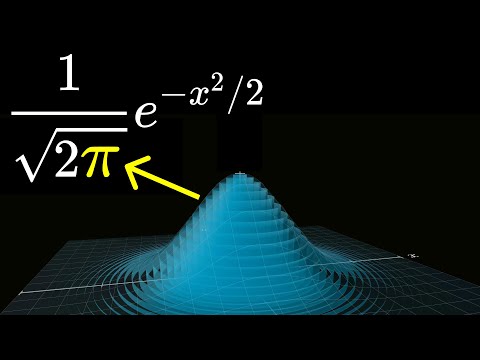

And when you strip away all of the different parameters and the constants, the basic function that describes the bell curve shape is e to the negative x squared. And the reason that pi showed up in the final formula was that the area underneath this curve works out, as you will see in a couple minutes, to be the square root of pi. So what that meant for us was that at some point we needed to divide out by that square root of pi to make sure that the area under the curve is one, which is a requirement before you can interpret it as a probability distribution.

In the full formula that you would see, say, in a stats book, this gets mixed together with some of the other constants, but in its purest form that pi originates from the area underneath this curve. So step number one for you and me is to explain that area, but I want to emphasize it's not the last step. To satisfy the question raised by that hypothetical statistician's friend, we need to go further.

We need to also answer why is it that this function e to the negative x squared is so special in the first place? I mean, there are lots of different formulas you could write down that would give a shape that, you know, vaguely bulges in the middle and tapers out on either side. So why is it that this specific function holds such a special place in statistics?

To phrase our goal another way, can we find a connection between the proof that shows why pi shows up and the central limit theorem, which, as we talked about in the last video, is the thing that explains when you can expect a normal distribution to arise in nature. So with all of that as the goal, first things first, let's dig into the classic and very beautiful proof. All right, when you want to find the area underneath a curve, the tool for doing that is an integral.

As a quick reminder for how you might read this notation, you might imagine approximating that area with many different rectangles under the curve, where the height of each such rectangle is the value of the function above that point, in this case, e to the negative x squared for a certain input x, and the width is some little number that we're calling dx. We need to add up the areas of all these rectangles, for values of x ranging from negative infinity up to infinity, and the use of that notation dx is kind of meant to imply you shouldn't think of any specific width, but instead you ask, as the chosen width for your rectangles gets thinner and thinner, what does this sum of all those areas approach? Of course, all of that is just notation unless you provide a way to answer that question, and the magic of calculus is that it provides just that, at least usually.

You see, usually the procedure here would be to find some function whose derivative is equal to the stuff we have on the inside, e to the negative x squared. In other words, we want to find an antiderivative of that function. The problem is, for this particular function, it is provably not possible to find such an antiderivative.

It's a little weird and beyond the scope of what I want to talk about here, but basically, even though there exists an antiderivative, it is a well-defined function, you cannot express what that antiderivative is using all our usual tools, like polynomial expressions, trig functions, exponentials, or any way to mix them together. So finding this area requires a bit of cleverness. There needs to be a new trick that we bring to bear.

And the first step to this trick is easily the most absurd. We start by bumping things up one dimension, so that instead of asking for the area under a bell curve, we ask for the volume underneath this kind of bell surface. You could rightly ask, why would you do that?

Who ordered another dimension? And I'll admit, it's not terribly motivated right now, other than to say, watch what happens when we just try it. In general, with hard problems, it's never a bad idea to try solving cousins of the problem, since that can help you get a little bit of momentum and insight.

To be clear on how this higher dimensional function is defined, it takes in two different inputs, x and y, which we might think of as a point on the xy-plane. And the way to think about it is to consider the distance from that point to the origin, which I'll label as r, and then to plug in that distance to our original bell curve function, that is, we take e to the negative r squared. You might notice the lines I've drawn on this diagram make a right triangle.

So, by the Pythagorean theorem, x squared plus y squared equals r squared. So in the function I have written, where you see x squared plus y squared, you can think in the back of your mind, that's really the square of the distance from the point to the origin. The main thing to notice here is how this gives our function a kind of circular symmetry, in the sense that all of the inputs that sit on a given circle have the same output.

And so when we graph this function in three dimensions, it means it has a rotational symmetry about the z-axis. Math tends to reward you when you respect its symmetries, so for our question of computing the volume underneath the surface, what we're going to do is respect that symmetry, and imagine integrating together a bunch of thin little cylinders underneath that surface. Here, making this a little more quantitative, let's focus on just one of those cylindrical shells, where its area is going to be the circumference of that shell times the height.

You might imagine it as something like the label on a soup can that we can unwrap into a rectangle. The circumference of the cylinder, which is the top side of that rectangle, is going to be 2 pi times the radius. And then the height of our cylinder, the other side of our rectangle, is the height of the surface at this point, which by definition is the value of our function associated with that radius, which like I said earlier you can think of as e to the negative r squared.

The real way you want to think about this is to give that cylinder a little bit of thickness, which we'll call dr, so that the volume that it represents is approximately that area we just looked at multiplied by this thickness dr. Our task now is to integrate together, or add together, all of these different cylinders as r ranges between 0 and infinity. Or more precisely, we consider what happens as that thickness gets thinner and thinner, approaching 0, and we add together the volumes of the many many many different thin cylinders that sit underneath that curve.

You might think this is just a harder version of what we were looking at earlier, three dimensions should be more complicated than two. But actually something very helpful has happened. First let me clean up a little by factoring the pi outside that integral.

Now the stuff inside that integral, having picked up this term 2r, does have an antiderivative. We can now apply the usual tactics of calculus. Specifically, that whole inside expression is the derivative of negative e to the negative r squared.

And so, those of you comfortable with calculus know what to do from here. We take that antiderivative and plug in the upper bound, which is negative infinity squared, and that gives us 0, or speaking a little bit more precisely, if you consider the limit of this expression as the input approaches infinity, the limiting value is 0, and we subtract off the value of that antiderivative at the lower bound, 0, which in this case is negative 1. So all in all, the whole integral just works out to be 1, which means all we're left with is that factor out in front, pi.

Evidently, the volume underneath this bell surface is pi. And I'll point out in this case, it's not wild that pi shows up, because the surface has this intrinsic circular symmetry. Still, you might wonder, how does that help us?

As I said, throughout math, if you face a hard problem, solving an adjacent problem can be unexpectedly helpful as a next step. And in this case, it's helpful not just for building intuition, but we can directly relate the three-dimensional graph to our two-dimensional graph by analyzing the volume in a second, different way. You see, the more general way to approach volumes underneath surfaces is to think of chopping it up into slices that are all parallel to one of the axes.

For example, all these slices that are parallel to the x-axis. For example, this right here is a slice that corresponds to the plane y equals 0. You might notice it looks just like a bell curve, and if we write out the function, this should actually make a lot of sense.

You could just plug in y equals 0, but to help see what happens with other slices, notice how, thanks to the rules of exponentiation, we could also write our function as e to the negative x squared times e to the negative y squared. It factors out nicely. On this slice, that e to the negative y squared is just a number, specifically the number 1.

So this is the same graph we've seen before, e to the negative x squared, meaning that the area of this slice is exactly the thing that we're looking for. It's the mystery constant, which I'm going to give the name c. What's nice is there's nothing really special about this particular slice.

If we chose a different slice corresponding to a different y value, it corresponds to multiplying this curve by a different number. So it's the same basic shape, just scaled down by that number, meaning its area is the same as our mystery constant, just scaled down by some number. That's pretty cool.

Each one of these slices has the same basic shape, just rescaled in the vertical direction, which, by the way, is not at all true for most two-variable functions. This is very much dependent on the fact that we were able to factor our function into one part that's just dependent on the y and another part that's just dependent on the x. Now, to think about the volume underneath this whole surface, here's another way we could phrase it.

We're going to compute another integral that ranges from y equals negative infinity up to infinity, where the term inside that integral tells us the area of each one of those slices. And when we multiply it by a little thickness dy, you might think of it as giving each one of those slices a little bit of volume. And remember, that term c sitting in front represents the thing we want to know, which itself is an integral, a suspiciously similar-looking integral.

See, if we take the expression on the top and we factor out that constant c, because it's just a number, it doesn't depend on y, the thing we're left with, the integral we need to compute, is exactly the mystery constant, the thing we don't know. So overall, the volume underneath this bell surface works out to be this mystery constant squared. Out of context, this might seem very unhelpful, it's just relating one thing we don't know to another thing we don't know, except we've already computed the volume under this surface, we know that it's equal to pi.

Therefore, the mystery constant we want to know, the area underneath this bell curve, must be the square root of pi. It's a very pretty argument, but a few things are not entirely satisfying. For one thing, it feels a little bit like a trick, something that just happened to work without offering much of a sense for how you could have rediscovered it yourself.

Also, if we think back to our imagined statistician's friend, it doesn't really answer their question, which was what do circles have to do with population statistics? Like I said, it's the first step, not the last, and as our next step, let's see if we can unpack why this proof is not quite as wild and arbitrary as you might first think, and how it relates to an explanation for where this function e to the negative x squared is coming from in the first place. John Herschel was this mathematician slash scientist slash inventor who really did all sorts of things throughout the 19th century.

He made contributions in chemistry, astronomy, photography, botany, he invented the blueprint and named many of the moons in our solar system, and in the midst of all of this, he also offered a very elegant little derivation for the Gaussian distribution in 1850. The setup is to imagine that you want to describe some kind of probability distribution in two-dimensional space. For instance, maybe you want to model the probability density for hits on a dartboard.

What Herschel showed is that if you want this distribution to satisfy two pretty reasonable seeming properties, your hand is unexpectedly forced, and even if you had never heard of a Gaussian in your life, you would be inexorably drawn to use a function with the shape e to the negative x squared plus y squared. You do have one degree of freedom to control the spread of that distribution, and of course there's going to be some constant sitting in front to make sure it's normalized, but the point is that we're forced into this very specific kind of bell curve shape. The first of these two properties is that the probability density around each point depends only on its distance from the origin, not on its direction.

So on a dartboard with everybody aiming for the bullseye, this would mean that you could rotate the board and it would make no difference for the distribution. Mathematically, this means that the function describing your probability distribution, which I'll call f2 since it takes in two inputs x and y, well it can be expressed as some single variable function of the radius r. And just to spell it out, r is the distance between the point xy and the origin, the square root of x squared plus y squared.

Property number two is that the x and y coordinates of each point are independent from each other, which is to say if you learn the x coordinate of a point, it would give you no information about the y coordinate. The way this looks as an equation is that our function, which describes the probability density around each point on the xy plane, can be factored into two different parts, one of which can be purely written in terms of x, this is the distribution of the x coordinate, I'm giving it the name g, and the other part is purely in terms of y, this would be the distribution for the y coordinate, which I'm temporarily calling h. But if you combine this with the assumption that things are radially symmetric, both of these should be the same distribution, the behavior on each axis should look the same.

So we could also write this as g of x times g of y, it's the same function. And more than that, this function is actually going to be proportional to the one we were looking at, the one that describes our probability density as a function of the radius, the distance away from the origin. To see this, imagine you were to analyze a point that was on the x-axis, a distance r away from the origin.

Then the two distinct ways to express our function based on the two different properties tells us that f of r has to equal some constant multiplied by g of r. So these functions f and g are basically the same thing, just up to some constant multiple. And you know what?

It would be really nice if we could just assume that that constant was one, so that f and g were literally the same function. And what I'm going to do, which might feel a little bit cheeky, is just assume that that is the case. What this means is that our answer is going to be a little bit wrong.

The function that we will deduce describing this distribution will be off by some constant factor. But that's no big deal, because in the end we can just rescale to make sure the area under the curve is one, like we always do with probability distributions. Now, if f and g are the same thing, this gives us a very nice little equation purely in terms of the function f.

Remember what this function f is. If you have some point in the xy-plane, a distance r from the origin, then f of r tells you the relative likelihood of that point showing up in the random process. More specifically, it gives the probability density of that point.

At the outset, this function could have been anything, but Herschel's two different properties evidently imply something kind of funny about it, which is that if we take the x and y coordinates of that point on the plane and evaluate this function on them separately, taking f of x times f of y, it should give us the same result. Or if you prefer, we could expand out the meaning of that distance r as the square root of x squared plus y squared, and this is what our key equation looks like. This kind of equation is what's known in the business as a functional equation.

We're not solving for an unknown number. Instead, we're saying that the equation is true for all possible numbers x and y, and the thing we're trying to find is an unknown function. In the back of your mind, you can think we already know one function that satisfies this property, e to the negative x squared, and as a sanity check, you might verify for yourself that it does satisfy that.

Of course, the point is to pretend that you don't know that, and to instead deduce what all of the functions are which satisfy this property. In general, functional equations can be quite tricky, but let me show you how you can solve this one. First, it's nice to introduce a little helper function that I'll call h of x, which will be defined as our mystery function evaluated at the square root of x.

Said another way, h of x squared is the same thing as f of x. For example, in the back of your mind where you know that e to the negative x squared will happen to be one of the answers, this little helper function h would be e to the negative x. But again, we're pretending like we don't know that.

The reason for doing this is that the key property for f looks a little bit nicer if we phrase it in terms of this helper function h, because now what it's saying is if you take two arbitrary positive numbers and you add them up and evaluate h, it's the same thing as evaluating h on them separately and then multiplying the results. In a sense, it turns addition into multiplication. Some of you might see where this is going, but let's take a moment to walk through why this forces our hand.

As a next step, you might want to pause and convince yourself that if this property is true for the sum of two numbers, this property also must be true if we add up an arbitrary number of inputs. To get a feel for why this is so constraining, think about plugging in a whole number, something like h of 5. Because you can write 5 as 1 plus 1 plus 1 plus 1 plus 1, this key property means that it must equal h of 1 multiplied by itself five times.

Of course, there's nothing special about 5. I could have chosen any whole number n, and we'd be forced to conclude that the function looks like some number raised to the power n. And let's go ahead and give that number a name, like b for the base of our exponential.

As a little mini exercise here, see if you can pause and take a moment to convince yourself that the same is true for a rational input, that if you plug in p over q to this function, it must look like this base b raised to the power p over q. And as a hint, you might want to think about adding that input to itself q different times. And then because rational numbers are dense in the real number line, if we make one more pretty reasonable assumption that we only care about continuous functions, this is enough to force your hand completely and say that h has to be an exponential function, b to the power x, for all real number inputs x.

I guess to be more precise I should say for all positive real inputs. The way we defined h, it's only taking in positive numbers. Now, as we've gone over before, instead of writing down exponential functions as some base raised to the power x, mathematicians often like to write them as e to the power of some constant c times x.

Making the choice to always use e as a base while letting that constant c determine which specific exponential function you're talking about just makes everything much easier any time calculus comes wandering along your path. And so this means that our target function f has to look like e to the power of some constant times x squared. The beauty is that that function is no longer something that was merely handed down to us from on high.

Instead we started with these two different premises for how we wanted a distribution in two dimensions to behave, and we were drawn to the conclusion that the shape of the expression describing that distribution as a function of the radius away from the origin has to be e to the power of some constant times that radius squared. You'll remember I said earlier this answer will be off by a factor of a constant. We need to rescale it to make it a valid probability distribution, and geometrically you might think of that as scaling it so that the volume under the surface is equal to one.

Now you might notice that for positive values of this constant in the exponent c, our function blows up to infinity in all directions, so the volume under that surface would be infinite, meaning it's not possible to renormalize. You can't turn it into a probability distribution. And that leaves us with the last constraint, which is that this constant in the exponent has to be a negative number, and the specific value of that number determines the spread of the distribution.

Ten years after Herschel wrote this, James Clerk Maxwell, who's most well known for having written down the fundamental equations for electricity and magnetism, independently stumbled across the same derivation. In his case he was doing it in three dimensions since he was doing statistical mechanics and he was deriving a formula for the distribution for velocities of molecules in a gas, but the logic all works out the same. For you and me, if we view this as the defining property of a Gaussian, then it's a little bit less surprising that pi might make an appearance.

After all, circular symmetry was part of this defining property. More than that, it makes the clever proof that we saw earlier feel a little bit less out of the blue. I mean, a key problem-solving principle in math is to use the defining features of your setup, and if you had been primed by this Herschel-Maxwell derivation, where the defining property for a Gaussian is this coincidence of having a distribution that's both radially symmetric and also independent along each axis, then the very first step of our proof, which seemed so strange bumping the problem up one dimension, was really just a way of opening the door to let that defining property make itself visible.

And if you think back, the essence of the proof came down to using that radial symmetry on the one hand, and then also using the ability to factor the function on the other. From this standpoint, using both those facts feels less like a trick that happened to work, and more like an inevitable necessity. Nevertheless, thinking once again of our statistician's friend, this is still not entirely satisfying.

Using the Herschel-Maxwell derivation, saying this property of a multi-dimensional distribution is what defines a Gaussian, well that presumes that we're already in some kind of multi-dimensional situation in the first place. Much more commonly, the way that a normal distribution arises in practice doesn't feel spatial or geometric at all. It stems from the central limit theorem, which is all about adding together many different independent variables.

So to bring it all home here, what we need to do is explain why the function that's characterized by this Herschel-Maxwell derivation should be the same thing as the function that sits at the heart of the central limit theorem. And at this point, those of you following along are probably going to make fun of me, I think it makes sense to pull this last step out as its own video. Oh, and one final footnote here.

After making a Patreon post about this particular project, one patron, who's a mathematician named Kevin Ega, shared something completely delightful that I had never seen before, which is that if you apply this integration trick in higher dimensions, it lets you derive the formulas for volumes of higher dimensional spheres. It's a very fun exercise, I'm leaving the details up on the screen for any viewers who are comfortable with integration by parts. Thank you very much to Kevin for sharing that one, and thanks to all patrons, by the way, both for the support of the channel, and also for all the feedback you offer on the early drafts of videos.

Thank you.

Related Videos

31:15

But what is the Central Limit Theorem?

3Blue1Brown

3,452,230 views

17:26

Researchers thought this was a bug (Borwei...

3Blue1Brown

3,526,689 views

![The most beautiful equation in math, explained visually [Euler’s Formula]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/f8CXG7dS-D0/mqdefault.jpg)

26:57

The most beautiful equation in math, expla...

Welch Labs

569,448 views

22:21

Why do prime numbers make these spirals? |...

3Blue1Brown

5,737,751 views

11:57

The Definition of the Gamma function

William Tu

3,097 views

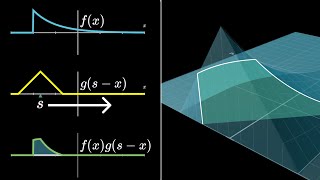

27:25

Convolutions | Why X+Y in probability is a...

3Blue1Brown

671,974 views

10:00

The Bernoulli Integral is ridiculous

Dr. Trefor Bazett

700,837 views

19:22

Using topology for discrete problems | The...

3Blue1Brown

873,756 views

21:05

Why is there no equation for the perimeter...

Stand-up Maths

2,191,760 views

15:01

how Laplace solved the Gaussian integral

blackpenredpen

739,196 views

24:28

Euler's formula with introductory group th...

3Blue1Brown

2,440,040 views

8:10

ALL of calculus 3 in 8 minutes.

gregorian calendar

1,161,588 views

27:36

Beyond the Mandelbrot set, an intro to hol...

3Blue1Brown

1,468,546 views

12:59

The Boundary of Computation

Mutual Information

1,012,386 views

5:45

Why does pi show up here? | The Gaussian I...

vcubingx

242,046 views

21:58

Group theory, abstraction, and the 196,883...

3Blue1Brown

3,049,412 views

22:38

How To Catch A Cheater With Math

Primer

4,991,646 views

21:23

Euler's Formula - Numberphile

Numberphile

346,906 views

49:49

Way beyond the golden ratio: The power of ...

Mathologer

101,198 views

12:19

Every Important Math Constant Explained

ThoughtThrill

100,272 views