But what is a neural network? | Chapter 1, Deep learning

17.2M views3361 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

What are the neurons, why are there layers, and what is the math underlying it?

Help fund future pro...

Video Transcript:

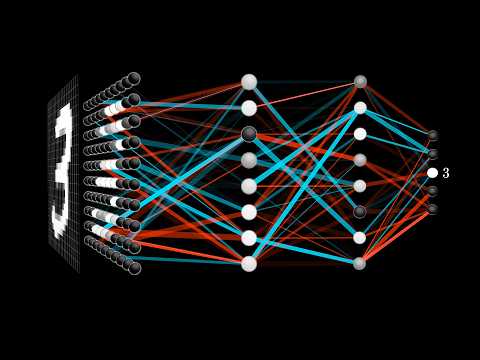

This is a 3. It's sloppily written and rendered at an extremely low resolution of 28x28 pixels, but your brain has no trouble recognizing it as a 3. And I want you to take a moment to appreciate how crazy it is that brains can do this so effortlessly.

I mean, this, this and this are also recognizable as 3s, even though the specific values of each pixel is very different from one image to the next. The particular light-sensitive cells in your eye that are firing when you see this 3 are very different from the ones firing when you see this 3. But something in that crazy-smart visual cortex of yours resolves these as representing the same idea, while at the same time recognizing other images as their own distinct ideas.

But if I told you, hey, sit down and write for me a program that takes in a grid of 28x28 pixels like this and outputs a single number between 0 and 10, telling you what it thinks the digit is, well the task goes from comically trivial to dauntingly difficult. Unless you've been living under a rock, I think I hardly need to motivate the relevance and importance of machine learning and neural networks to the present and to the future. But what I want to do here is show you what a neural network actually is, assuming no background, and to help visualize what it's doing, not as a buzzword but as a piece of math.

My hope is that you come away feeling like the structure itself is motivated, and to feel like you know what it means when you read, or you hear about a neural network quote-unquote learning. This video is just going to be devoted to the structure component of that, and the following one is going to tackle learning. What we're going to do is put together a neural network that can learn to recognize handwritten digits.

This is a somewhat classic example for introducing the topic, and I'm happy to stick with the status quo here, because at the end of the two videos I want to point you to a couple good resources where you can learn more, and where you can download the code that does this and play with it on your own computer. There are many many variants of neural networks, and in recent years there's been sort of a boom in research towards these variants, but in these two introductory videos you and I are just going to look at the simplest plain vanilla form with no added frills. This is kind of a necessary prerequisite for understanding any of the more powerful modern variants, and trust me it still has plenty of complexity for us to wrap our minds around.

But even in this simplest form it can learn to recognize handwritten digits, which is a pretty cool thing for a computer to be able to do. And at the same time you'll see how it does fall short of a couple hopes that we might have for it. As the name suggests neural networks are inspired by the brain, but let's break that down.

What are the neurons, and in what sense are they linked together? Right now when I say neuron all I want you to think about is a thing that holds a number, specifically a number between 0 and 1. It's really not more than that.

For example the network starts with a bunch of neurons corresponding to each of the 28x28 pixels of the input image, which is 784 neurons in total. Each one of these holds a number that represents the grayscale value of the corresponding pixel, ranging from 0 for black pixels up to 1 for white pixels. This number inside the neuron is called its activation, and the image you might have in mind here is that each neuron is lit up when its activation is a high number.

So all of these 784 neurons make up the first layer of our network. Now jumping over to the last layer, this has 10 neurons, each representing one of the digits. The activation in these neurons, again some number that's between 0 and 1, represents how much the system thinks that a given image corresponds with a given digit.

There's also a couple layers in between called the hidden layers, which for the time being should just be a giant question mark for how on earth this process of recognizing digits is going to be handled. In this network I chose two hidden layers, each one with 16 neurons, and admittedly that's kind of an arbitrary choice. To be honest I chose two layers based on how I want to motivate the structure in just a moment, and 16, well that was just a nice number to fit on the screen.

In practice there is a lot of room for experiment with a specific structure here. The way the network operates, activations in one layer determine the activations of the next layer. And of course the heart of the network as an information processing mechanism comes down to exactly how those activations from one layer bring about activations in the next layer.

It's meant to be loosely analogous to how in biological networks of neurons, some groups of neurons firing cause certain others to fire. Now the network I'm showing here has already been trained to recognize digits, and let me show you what I mean by that. It means if you feed in an image, lighting up all 784 neurons of the input layer according to the brightness of each pixel in the image, that pattern of activations causes some very specific pattern in the next layer which causes some pattern in the one after it, which finally gives some pattern in the output layer.

And the brightest neuron of that output layer is the network's choice, so to speak, for what digit this image represents. And before jumping into the math for how one layer influences the next, or how training works, let's just talk about why it's even reasonable to expect a layered structure like this to behave intelligently. What are we expecting here?

What is the best hope for what those middle layers might be doing? Well, when you or I recognize digits, we piece together various components. A 9 has a loop up top and a line on the right.

An 8 also has a loop up top, but it's paired with another loop down low. A 4 basically breaks down into three specific lines, and things like that. Now in a perfect world, we might hope that each neuron in the second to last layer corresponds with one of these subcomponents, that anytime you feed in an image with, say, a loop up top, like a 9 or an 8, there's some specific neuron whose activation is going to be close to 1.

And I don't mean this specific loop of pixels, the hope would be that any generally loopy pattern towards the top sets off this neuron. That way, going from the third layer to the last one just requires learning which combination of subcomponents corresponds to which digits. Of course, that just kicks the problem down the road, because how would you recognize these subcomponents, or even learn what the right subcomponents should be?

And I still haven't even talked about how one layer influences the next, but run with me on this one for a moment. Recognizing a loop can also break down into subproblems. One reasonable way to do this would be to first recognize the various little edges that make it up.

Similarly, a long line, like the kind you might see in the digits 1 or 4 or 7, is really just a long edge, or maybe you think of it as a certain pattern of several smaller edges. So maybe our hope is that each neuron in the second layer of the network corresponds with the various relevant little edges. Maybe when an image like this one comes in, it lights up all of the neurons associated with around 8 to 10 specific little edges, which in turn lights up the neurons associated with the upper loop and a long vertical line, and those light up the neuron associated with a 9.

Whether or not this is what our final network actually does is another question, one that I'll come back to once we see how to train the network, but this is a hope that we might have, a sort of goal with the layered structure like this. Moreover, you can imagine how being able to detect edges and patterns like this would be really useful for other image recognition tasks. And even beyond image recognition, there are all sorts of intelligent things you might want to do that break down into layers of abstraction.

Parsing speech, for example, involves taking raw audio and picking out distinct sounds, which combine to make certain syllables, which combine to form words, which combine to make up phrases and more abstract thoughts, etc. But getting back to how any of this actually works, picture yourself right now designing how exactly the activations in one layer might determine the activations in the next. The goal is to have some mechanism that could conceivably combine pixels into edges, or edges into patterns, or patterns into digits.

And to zoom in on one very specific example, let's say the hope is for one particular neuron in the second layer to pick up on whether or not the image has an edge in this region here. The question at hand is what parameters should the network have? What dials and knobs should you be able to tweak so that it's expressive enough to potentially capture this pattern, or any other pixel pattern, or the pattern that several edges can make a loop, and other such things?

Well, what we'll do is assign a weight to each one of the connections between our neuron and the neurons from the first layer. These weights are just numbers. Then take all of those activations from the first layer and compute their weighted sum according to these weights.

I find it helpful to think of these weights as being organized into a little grid of their own, and I'm going to use green pixels to indicate positive weights, and red pixels to indicate negative weights, where the brightness of that pixel is some loose depiction of the weight's value. Now if we made the weights associated with almost all of the pixels zero except for some positive weights in this region that we care about, then taking the weighted sum of all the pixel values really just amounts to adding up the values of the pixel just in the region that we care about. And if you really wanted to pick up on whether there's an edge here, what you might do is have some negative weights associated with the surrounding pixels.

Then the sum is largest when those middle pixels are bright but the surrounding pixels are darker. When you compute a weighted sum like this, you might come out with any number, but for this network what we want is for activations to be some value between 0 and 1. So a common thing to do is to pump this weighted sum into some function that squishes the real number line into the range between 0 and 1.

And a common function that does this is called the sigmoid function, also known as a logistic curve. Basically very negative inputs end up close to 0, positive inputs end up close to 1, and it just steadily increases around the input 0. So the activation of the neuron here is basically a measure of how positive the relevant weighted sum is.

But maybe it's not that you want the neuron to light up when the weighted sum is bigger than 0. Maybe you only want it to be active when the sum is bigger than say 10. That is, you want some bias for it to be inactive.

What we'll do then is just add in some other number like negative 10 to this weighted sum before plugging it through the sigmoid squishification function. That additional number is called the bias. So the weights tell you what pixel pattern this neuron in the second layer is picking up on, and the bias tells you how high the weighted sum needs to be before the neuron starts getting meaningfully active.

And that is just one neuron. Every other neuron in this layer is going to be connected to all 784 pixel neurons from the first layer, and each one of those 784 connections has its own weight associated with it. Also, each one has some bias, some other number that you add on to the weighted sum before squishing it with the sigmoid.

And that's a lot to think about! With this hidden layer of 16 neurons, that's a total of 784 times 16 weights, along with 16 biases. And all of that is just the connections from the first layer to the second.

The connections between the other layers also have a bunch of weights and biases associated with them. All said and done, this network has almost exactly 13,000 total weights and biases. 13,000 knobs and dials that can be tweaked and turned to make this network behave in different ways.

So when we talk about learning, what that's referring to is getting the computer to find a valid setting for all of these many many numbers so that it'll actually solve the problem at hand. One thought experiment that is at once fun and kind of horrifying is to imagine sitting down and setting all of these weights and biases by hand, purposefully tweaking the numbers so that the second layer picks up on edges, the third layer picks up on patterns, etc. I personally find this satisfying rather than just treating the network as a total black box, because when the network doesn't perform the way you anticipate, if you've built up a little bit of a relationship with what those weights and biases actually mean, you have a starting place for experimenting with how to change the structure to improve.

Or when the network does work but not for the reasons you might expect, digging into what the weights and biases are doing is a good way to challenge your assumptions and really expose the full space of possible solutions. By the way, the actual function here is a little cumbersome to write down, don't you think? So let me show you a more notationally compact way that these connections are represented.

This is how you'd see it if you choose to read up more about neural networks. 214 00:13:41,380 --> 00:13:40,520 Organize all of the activations from one layer into a column as a vector. Then organize all of the weights as a matrix, where each row of that matrix corresponds to the connections between one layer and a particular neuron in the next layer.

What that means is that taking the weighted sum of the activations in the first layer according to these weights corresponds to one of the terms in the matrix vector product of everything we have on the left here. By the way, so much of machine learning just comes down to having a good grasp of linear algebra, so for any of you who want a nice visual understanding for matrices and what matrix vector multiplication means, take a look at the series I did on linear algebra, especially chapter 3. Back to our expression, instead of talking about adding the bias to each one of these values independently, we represent it by organizing all those biases into a vector, and adding the entire vector to the previous matrix vector product.

Then as a final step, I'll wrap a sigmoid around the outside here, and what that's supposed to represent is that you're going to apply the sigmoid function to each specific component of the resulting vector inside. So once you write down this weight matrix and these vectors as their own symbols, you can communicate the full transition of activations from one layer to the next in an extremely tight and neat little expression, and this makes the relevant code both a lot simpler and a lot faster, since many libraries optimize the heck out of matrix multiplication. Remember how earlier I said these neurons are simply things that hold numbers?

Well of course the specific numbers that they hold depends on the image you feed in, so it's actually more accurate to think of each neuron as a function, one that takes in the outputs of all the neurons in the previous layer and spits out a number between 0 and 1. Really the entire network is just a function, one that takes in 784 numbers as an input and spits out 10 numbers as an output. It's an absurdly complicated function, one that involves 13,000 parameters in the forms of these weights and biases that pick up on certain patterns, and which involves iterating many matrix vector products and the sigmoid squishification function, but it's just a function nonetheless.

And in a way it's kind of reassuring that it looks complicated. I mean if it were any simpler, what hope would we have that it could take on the challenge of recognizing digits? And how does it take on that challenge?

How does this network learn the appropriate weights and biases just by looking at data? Well that's what I'll show in the next video, and I'll also dig a little more into what this particular network we're seeing is really doing. Now is the point I suppose I should say subscribe to stay notified about when that video or any new videos come out, but realistically most of you don't actually receive notifications from YouTube, do you?

Maybe more honestly I should say subscribe so that the neural networks that underlie YouTube's recommendation algorithm are primed to believe that you want to see content from this channel get recommended to you. Anyway, stay posted for more. Thank you very much to everyone supporting these videos on Patreon.

I've been a little slow to progress in the probability series this summer, but I'm jumping back into it after this project, so patrons you can look out for updates there. To close things off here I have with me Lisha Li who did her PhD work on the theoretical side of deep learning and who currently works at a venture capital firm called Amplify Partners who kindly provided some of the funding for this video. So Lisha one thing I think we should quickly bring up is this sigmoid function.

As I understand it early networks use this to squish the relevant weighted sum into that interval between zero and one, you know kind of motivated by this biological analogy of neurons either being inactive or active. Exactly. But relatively few modern networks actually use sigmoid anymore.

Yeah. It's kind of old school right? Yeah or rather ReLU seems to be much easier to train.

And ReLU, ReLU stands for rectified linear unit? Yes it's this kind of function where you're just taking a max of zero and a where a is given by what you were explaining in the video and what this was sort of motivated from I think was a partially by a biological analogy with how neurons would either be activated or not. And so if it passes a certain threshold it would be the identity function but if it did not then it would just not be activated so it'd be zero so it's kind of a simplification.

Using sigmoids didn't help training or it was very difficult to train at some point and people just tried ReLU and it happened to work very well for these incredibly deep neural networks. All right thank you Lisha.

Related Videos

20:33

Gradient descent, how neural networks lear...

3Blue1Brown

6,991,532 views

23:34

Why Democracy Is Mathematically Impossible

Veritasium

3,677,079 views

22:43

How might LLMs store facts | Chapter 7, De...

3Blue1Brown

379,362 views

26:09

Computer Scientist Explains Machine Learni...

WIRED

2,401,846 views

23:01

But what is a convolution?

3Blue1Brown

2,640,128 views

27:15

The Most Misunderstood Concept in Physics

Veritasium

14,903,778 views

27:14

But what is a GPT? Visual intro to transf...

3Blue1Brown

3,017,279 views

![The moment we stopped understanding AI [AlexNet]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/UZDiGooFs54/mqdefault.jpg)

17:38

The moment we stopped understanding AI [Al...

Welch Labs

1,014,084 views

9:06

10 weird algorithms

Fireship

1,251,263 views

37:03

Something Strange Happens When You Follow ...

Veritasium

13,611,740 views

53:33

Your Brain: Who's in Control? | Full Docum...

NOVA PBS Official

3,963,086 views

34:29

I Took an IQ Test to Find Out What it Actu...

Veritasium

8,343,734 views

12:48

Has Generative AI Already Peaked? - Comput...

Computerphile

978,548 views

1:09:58

MIT Introduction to Deep Learning | 6.S191

Alexander Amini

534,887 views

26:10

Attention in transformers, visually explai...

3Blue1Brown

1,535,792 views

46:02

What is generative AI and how does it work...

The Royal Institution

994,320 views

26:52

A Brain-Inspired Algorithm For Memory

Artem Kirsanov

100,243 views

15:11

Bayes theorem, the geometry of changing be...

3Blue1Brown

4,381,617 views

40:08

The Most Important Algorithm in Machine Le...

Artem Kirsanov

410,101 views

51:31

11. Introduction to Machine Learning

MIT OpenCourseWare

1,644,909 views