How wiggling charges give rise to light

1.11M views3976 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

Explaining the barber pole effect from the last video: https://youtu.be/QCX62YJCmGk

Next video on th...

Video Transcript:

In the last video, you and I looked at this demo here, where we shine linearly polarized light through a tube full of sugar water, and we saw how it rather mysteriously results in these colored diagonal stripes. There, I walked through the general outline for an explanation, keeping track of what questions still need to be answered. Namely, why does sugar water twist the polarization direction of light?

Why does that twisting rate depend on the color of the light? And why, even if you understand that this twist is happening, would you see any evidence of it when viewing the tube from the side, with no additional polarizing filters? Here, I'd like to begin with the very fundamental idea of what light is, and show how the answer to these questions can emerge from an extremely minimal set of assumptions.

In some sense, the fundamental question of electricity and magnetism is how the position and motion of one charged particle influences that of another. For example, one of the first things you learn, say in a high school physics class, is that charges with the same sign tend to repel each other. And the strength of this force depends a lot on the distance between them.

If your charges are close, that repulsive force is very strong, but it decays very rapidly as these particles go away from each other. Specifically, here's how you might see this written down as an equation, known as Coulomb's law. The force is proportional to the charge of both of the particles, where it's common to use the letter q.

There are some constants in there, which for our purposes we can just think of as one big proportionality constant. And the important fact is that you've got this 1 divided by r squared term, where r is the distance between them. So for example, if the distance between them increases by a factor of 3, the force that they're applying to each other goes down by a factor of 9.

Another way you might see a law like this written down is to focus on just one charged particle, and then say for every point in space, if there was a second charge there, what force would this first charge be applying to that second one? And instead of describing a force per se, you might see this written describing what's known as the electric field, which is just a way of saying what force would be applied to a unit charge. And in this context, the word field means there's a value associated with every single point in space.

So the way I have it written here, it depends on a little vector r, which would be the vector from our charge to a given point in space, and the direction of this field at all points is in the same direction as r. I bring up Coulomb's law to emphasize that it's not the full story. There are other ways that charges influence each other.

For example, here's a phenomenon that this law alone could not explain. If you wiggle one charge up and down, then after a little bit of a delay, a second charge some distance to its right will be induced to wiggle up and down as well. We can write down a second law, which you might think of as a correction term to be added to Coulomb's law, that describes what's going on here.

Suppose at some point in time t0, that first charge is accelerating. Then I'll let time play forward, but leave on the screen a kind of ghost of that particle indicating where it was and how it was accelerating at this time t0. After a certain delay, this causes a force on the second charge, and the equation describing this force looks something like this.

So again, it's proportional to the charge of both of the particles, and once more a common way to write it involves this pile of constants that you don't really need to worry about. The important factor I want you to notice is how the force also depends on the distance between the particles, but instead of decaying in proportion to r squared, it only decays in proportion to r. So over long distances, this is the force that dominates, and Coulomb's law is negligible.

And then finally, it depends on the acceleration of that first particle, but it's not the acceleration of that particle at the current time, it's whatever that acceleration was at some time in the past. How far in the past depends on the distance between the particles and the speed of light, denoted with c. The way to think about it is that any form of influence can't propagate any faster than this speed, c.

In fact, a more accurate description of Coulomb's law would also involve a delay term like this. Again, the intuitive way to read this equation is that wiggling a charge in one location after some delay causes a wiggle to a second charge in another location. And actually, the way I have it written right now is a little bit wrong.

Instead of the acceleration vector here, I should really be writing something like a perp, indicating the component of that acceleration vector which is perpendicular to the line drawn between the two charges. In other words, when you wiggle that first charge, the direction that the second charge wiggles is always perpendicular to the line between them, and the amount that it wiggles gets weaker and weaker when that line between them is more lined up with the initial acceleration. As before, this is something you might see written down in a way that describes a component of the electric field caused by just one charge.

Again, that means what force would be applied to a second charge at all possible different points in space. This component of the field is only ever non-zero when our first charge is moving somehow, when it has an acceleration vector on it. And because of this delay term, the effects on this field tend to radiate away from the charge.

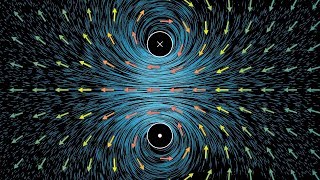

This is why I'm writing it down with the subscript rad. This is the component of the electric field that will radiate away from a given charge. For instance, when the charge is oscillating up and down, you get these propagating waves.

And for many of the vector fields I'll be showing, the intensity of the field is illustrated with the opacity of each little vector. This radiating influence is light, or more generally, electromagnetic radiation, including things like radio waves and x-rays and all that good stuff. As a side note, you sometimes see this propagation described a very different way that puts the fields front and center, using what are known as Maxwell's equations.

For our purposes, I want to focus just on this one law and show just how far it can take us when it comes to intuitions for light. For the animations I'm about to show, all I've really done is encoded in this one law, which tells us what should this component of the electric field be at every point in space, as determined by the history of accelerations of a particular charge. For example, if I set that charge oscillating up and down in the z direction, and illustrate this component of the electric field everywhere on the xy plane, you see these circular propagations of equal strength in all directions.

It's a little easier to think about if we focus on just one axis, like the x-axis. And at first when I made this animation, I assumed that there was some kind of bug, because near the charge it just looks crooked and wrong. But when you think about it, this is actually what you should expect, because remember, each one of these vectors is supposed to be perpendicular to the line drawn between that point and where the charge was at some point in the past.

At points that are far enough away from the charge, which is where this component of the field is what dominates anyway, the wiggling in the field is essentially parallel to the wiggling in the charge, which is why when we think about light waves, we're safe to think about the wiggling direction as being perpendicular to the propagation direction. Like I said, this propagation for just one charge is equally strong in all of the directions perpendicular to its wiggling, and really I should emphasize that the propagation does happen in all directions of three-dimensional space. It's maybe a little busy to try to illustrate the full three-dimensional vector field on screen like this, so it's clarifying if we just focus on, say, the xz plane.

Notice how the waves here are strongest in the x direction, but it still does propagate in all other directions, it's just that that propagation gets weaker in directions that are more aligned with the original wiggling. At the extreme, the only place where there's no propagation is in the z axis. Because our law has this 1 divided by r in it, the strength of the wave caused by just one particle does decay as you go farther away, in proportion to 1 over r.

But notice what happens if I take a whole row of charges, say oriented along the y axis, and I have them all start wiggling up and down in the z direction, and I illustrate the combined effects that all of them have on this component of the electric field. The effects of all these charges interfere deconstructively along the y direction, but they interfere constructively along the x direction. This is what it looks like for a beam of light to be concentrated along just one dimension.

So if you were to focus on the field just along the x axis, instead of decaying in proportion to 1 over r, this combined effect decays much more gently. In the extreme, you can get something arbitrarily close to those pure sine wave propagations we were illustrating earlier, if at some distance away you have a large number of charges oscillating in sync with each other like this. One thing that's worth emphasizing when you see light illustrated with a sine wave like this, is that even though that wave is being drawn in two or three dimensions, it's only describing the electric field along a one-dimensional line, namely the base of all those vectors.

It's just that to draw the vectors you have to venture off of that line. Great, so one of the last important things to highlight before we get back to the sugar water is polarization. In everything I've been showing, the driving charge is just oscillating along a single direction, like the z axis, and this causes linearly polarized light.

But it doesn't have to happen like that. For example, if I set the charge rotating in a little circle along the yz plane, meaning its acceleration vector is also rotating in a little circle, notice what the field looks like. This is known, aptly enough, as circularly polarized light.

Honestly, it's easiest to think about for just one point of the electric field. What it means for light to be circularly polarized is that at that point, the electric field vector is just rotating in a circle. People often find circular polarization a little confusing, and I suspect part of the reason for that is that it's hard to illustrate with a static diagram, but also it's a little confusing when you try to think about the full electric field.

For example, here's what the field looks like on the xy plane when I set that little charge rotating in a circle. It's certainly very beautiful, I could look at this all day, but you can understand why it might feel a little confusing. The very last thing I'll mention is that while everything here is a classical description of light, the important points still hold up in quantum mechanics.

You still have propagating waves, there's still polarization that can be either linear or circular. The main difference with quantum mechanics is that the energy in this wave doesn't scale up and down continuously, like you might expect, it comes in discrete little steps. I have another video that goes into more detail, but for our purposes, thinking about it classically is fine.

Part of the reason I wanted to go through that is because, frankly, it's just very fun to animate and I like an excuse for a fundamental lesson. But now let's turn back to our demo and see how we can build up an intuition for some of our key questions, starting from this very basic premise that shaking a charge in one location causes a shake to another charge a little bit later. And let's start by actually skipping ahead to question number three, why do we see the diagonal stripes?

To think about this, you need to imagine an observer to the side of the tube, and then for a particular pure color, say red, if the observer looks in the tube and sees that color, it's because light of that color has bounced off something at that point in the tube, and then propagated towards the eye of the observer. Sometimes when people talk about light bouncing off of things, the implied mental image is a projectile ricocheting off of some object, heading off in some random direction. But the better mental image to hold in your mind is that when the propagating light waves caused by some wiggling charge reach some second charge causing it to wiggle, that secondary wiggle results in its own propagation.

And for the animation on screen, that propagation goes back to the first charge, which itself causes a propagation towards the second. And this is what it looks like in a very simplified situation for light to bounce back and forth between two charges. If you have some concentrated beam of polarized light interacting with some charge, causing it to wiggle up and down, then these resulting second-order propagations are most strong in the directions perpendicular to the direction of polarization.

In some sense, you could think of light as bouncing off of that charge, but the important point is that it doesn't bounce in all directions equally. It's strongest perpendicular to the wiggle direction, but gets weaker in all of the other directions. So think about our setup, and for a particular frequency of light, how likely it is that an observer looking at a particular point in the tube will see that light.

Again, the key phenomenon with sugar water, which we have yet to explain, is that the polarization direction is slowly getting twisted as it goes down the tube. So suppose the observer was looking at a point like this one, where the polarization direction happens to be straight up and down. Then the second-order propagations resulting from wiggling charges at that point are most strong along the plane where the observer is, so the amount of red that they see at that point would look stronger.

By contrast, if they were looking at a different point in the tube like this one, where the wiggling direction is closer to being parallel to the line of sight, then the direction where the scattering is strongest is not at all aligned with the observer, and the amount of red they see is only going to be very weak. And looking at our actual physical setup, if we first pass the light through a filter showing only the red, we see exactly this effect in action. As you scan your eyes along the tube, the intensity of red that you see goes from being high to being low, where it's almost black, back to being high again.

As an analogy, imagine there was a ribbon going down the tube, always aligned with the polarization direction for this color, then putting yourself in the shoes of the observer, when you look at points where the ribbon appears very thin, you're going to see very little red light, whereas if you scan your eyes over to points where the ribbon appears thicker, you're going to see more red light. One thing that's nice about this is that if we try it for various different colors, you can actually see how the twisting rates are different for each one of the colors. Notice with red light, the distance between where it appears brightest and where it appears darkest is relatively long, whereas if you look down the colors of the rainbow, distance between the brightest point and the darkest point gets lower and lower.

So what you're seeing in effect is how red light twists slowly, whereas light waves with higher frequencies get twisted more aggressively. But still, you might wonder why the boundaries between light and dark points appear diagonal. Why is it that in addition to having variation as you scan your eyes from left to right, there's also variation as you scan your eyes from the top of the tube to the bottom?

This has less to do with what's going on in the tube, and more to do with a matter of perspective. Take a moment to think about many different parallel beams of light ranging from the top of the tube to the bottom. At the beginning, all of these light waves are wiggling up and down, and as you pass through the tube, and the effects of the sugar water somehow twists these directions, because they're all passing through the same amount of sugar, they're getting twisted by the same amounts.

So at all points, the polarization of these waves are parallel to each other. If you're the observer and you look at the topmost point here, its wiggling direction is essentially parallel to the line of sight, so the light scattering from that point is basically not going to reach your eyes at all. It should appear black.

But if you scan your eyes down the tube, the angle between the line of sight and the wiggling direction changes, and so there will be at least some component of red light scattering towards the eye. So as you scan your eyes from top to bottom, the amount of a particular color you see might vary, say from dark to light. The full demo that has white light is basically a combination of all these pure color patterns that go from light to dark to light with diagonal boundaries between the intense points and the weak points, hence why you see diagonal boundaries between the colors inside the tube.

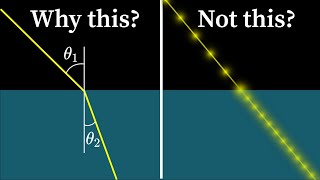

And now at last let's turn to the heart of the matter and try to explain why interactions with sugar would make light twist like this in the first place. It's related to the idea that light seems to slow down as it passes through a given medium. For example, if you look at the crests of a light wave as it goes into water, the crests through the water are traveling about 1.

33 times slower than the crests of that wave would travel in a vacuum. This number is what's called the index of refraction for water. In a bit, what I'd like to show is how this index of refraction can be explained by analyzing how the initial light wave shakes all the charges in the material and how the resulting second order propagations superimpose with that original light wave.

For right now, I'll just say that the interactions with each layer of the material ends up having the effect of slightly shifting back the phase of the wave, and on the whole, this gives the overall appearance that that wave moves slower as it passes through the material. Skipping ahead to what's going on with sugar, the relevant property of sucrose here is that it's what's called a chiral molecule, meaning it's fundamentally different from its mirror image. You could never reorient it in space to become identical to its mirror image.

It's like a left hand or a right hand. Or another much simpler example of a chiral shape is a spiral. If I take this right-handed spiral, then its mirror image is a left-handed spiral, and no matter how you try to rotate and reorient that first one, it'll never become identical to the second.

What's going on then is that the presence of a chiral molecule in the water like this introduces an asymmetry when it comes to interactions with light, specifically circularly polarized light. It turns out that the amount this chiral molecule slows down, say, left-handed circularly polarized light is different from the amount that it slows down right-handed circularly polarized light. Effectively, there's not one index of refraction, but two.

Now you might say that seems irrelevant to our setup, since we are very deliberately shining in linearly polarized light, there is no circularly polarized light. But actually there's a sense in which linearly polarized light is equal parts left-handed and right-handed circularly polarized light. Here, focus your attention on just one vector in this wave, wiggling straight up and down, which is to say polarized in the z direction.

Notice how it's possible to express this vector as a sum of two rotating vectors, one of them rotating at a constant rate counterclockwise, and the other one rotating clockwise. Adding them together tip to tail results in a vector oscillating on a line. In this case, it's a vertical line, but that direction can change based on the phase of the two vectors we're adding together.

Here, let me throw up a couple labels to keep track of how much each one of those two vectors has rotated in total, and then every now and then I'm going to slow down that first vector a little bit, and I want you to notice what happens to their sum. Well, every time I slow it down, effectively knocking back its phase a little bit, it causes the linearly wiggling sum to wiggle in a slightly different direction. So if the circularly polarized light wave represented by that left vector gets slowed down a little bit every time it runs across a sugar molecule, or at least slowed down more than its oppositely rotating counterpart would, the effect on the sum is to slowly rotate the direction of linear polarization.

And hence, as you look at slices further and further down the tube, the polarization direction does indeed get twisted the way we were describing earlier, representing how the composite effects with many many many different sugar molecules are slightly different for left-handed light than they are for right-handed light. As a nice way to test whether you understood everything up to this point, see if just by looking at the direction of the diagonal slices on our tube, you can deduce which kind of light the sugar is slowing down more, left-handed light or right-handed light. I'll call this a partial answer to our question number one, because it still leaves us wondering why there's an index of refraction in the first place, and how exactly it might depend on the polarization of the light, not just the material it's passing through.

Also, like I said at the start, a robust enough intuition here should also answer for us why the strength of this effect would depend on the frequency of the light. At this point I think we've covered quite enough for one video, so I'll pull out a discussion covering the origins of the index of refraction to a separate video. Thank you.

Related Videos

29:24

By why would light "slow down"? | Visualiz...

3Blue1Brown

1,609,372 views

9:57

This tests your understanding of light | T...

3Blue1Brown

1,112,045 views

29:08

I built a 1,000,000,000 fps video camera t...

AlphaPhoenix

927,285 views

17:26

Researchers thought this was a bug (Borwei...

3Blue1Brown

3,970,605 views

20:00

A Simple Diagram That Will Change How You ...

Astrum

154,182 views

16:02

What Does An Electron ACTUALLY Look Like?

PBS Space Time

650,464 views

22:59

The Dome Paradox: A Loophole in Newton's Laws

Up and Atom

1,718,044 views

27:26

This open problem taught me what topology is

3Blue1Brown

1,070,112 views

20:47

The Genius Behind the Quantum Navigation B...

Dr Ben Miles

1,453,590 views

15:42

Divergence and curl: The language of Maxw...

3Blue1Brown

4,459,084 views

21:16

Why Is MIT Making Robot Insects?

Veritasium

2,669,826 views

20:28

What is Spin? A Geometric explanation

ScienceClic English

512,068 views

![The moment we stopped understanding AI [AlexNet]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/UZDiGooFs54/mqdefault.jpg)

17:38

The moment we stopped understanding AI [Al...

Welch Labs

1,589,966 views

21:58

Group theory, abstraction, and the 196,883...

3Blue1Brown

3,191,301 views

28:30

How do Graphics Cards Work? Exploring GPU...

Branch Education

3,140,726 views

28:28

Russell's Paradox - a simple explanation o...

Jeffrey Kaplan

8,290,405 views

32:44

Is The Universe Just An Optimization Machine?

Veritasium

8,472,012 views

13:25

Answering viewer questions about refraction

3Blue1Brown

805,992 views

25:06

What is the i really doing in Schrödinger'...

Welch Labs

431,117 views

18:35

How Electricity Works - for visual learners

The Engineering Mindset

807,155 views