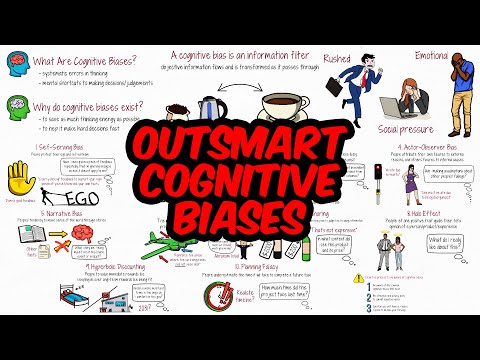

How to Make Better Decisions: 10 Cognitive Biases and How to Outsmart Them

78.41k views1286 WordsCopy TextShare

The Art of Improvement

✅ Full illustration: https://email.artofimprovement.co.uk/how-to-make-better-decisions

Don’t become...

Video Transcript:

What Are Cognitive Biases? A cognitive bias is a systematic error in thinking. It also works as a mental shortcut to making decisions or judgements.

Everyone is susceptible to cognitive bias, no matter their age, gender, or cultural background. Why do cognitive biases exist? Our brains need to take in an incredible amount of information but it also wants to save as much thinking energy as possible.

So, it relies on generalities or rules of thumb (also called heuristics) to help it make hard decisions fast. You can think of a cognitive bias as an information filter, through which objective information flows and is transformed as it passes through. Like coffee grounds and water changing into coffee — it’s the same ingredients but a slightly different experience once it’s transformed.

We usually rely on cognitive biases when we’re emotional, rushed to decide, or feel social pressure to make a choice. However, everyday thinking and decision-making are subject to cognitive biases as well. In this video, I’ve outlined ten common cognitive biases and ways to avoid them in your everyday thinking.

1. Self-Serving Bias This is the tendency for people to protect their ego and self-esteem. It often takes the form of “cherry-picking” feedback to support your high opinion of yourself or overlooking your own faults and failures.

You might be dismissing good feedback because you don’t want to bruise your ego. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “Have I been given a piece of feedback repeatedly, that I’m ignoring because I believe it doesn’t apply to me? ” 2.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) This is a form of social anxiety that makes people scared they’re being left out of exciting or interesting events. It can be triggered by posts on social media, where it looks like everyone is having fun without you. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “Do I feel left out of an invisible ‘in-crowd’?

Am I doing something because I want to, or because I’ll feel left out if I don’t? 3. Gambler’s Fallacy This principle describes peoples’ tendency to think a random event is less likely to happen in the future if it’s happened in the past.

For example, if I flip a coin that lands on heads 100 times in a row, most people assume it will land on tails next. But actually, each new flip is independent of what’s happened in the past. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “Is this event dependent or independent from past outcomes?

In other words, am I judging a random event by unrelated historical events? If I didn’t know anything about past performance, would I still make the same choice? ” 4.

Actor-Observer Bias This is the tendency for people to attribute their own failures to external reasons, and others failures to internal causes. For example, when you’re late, it’s because there was too much traffic. But you assume that Jane was late because she is disorganized.

TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “Am I making assumptions about other peoples’ failings? Have I let myself off the hook for bad behavior one too many times, while being tough on your colleagues, friends, or family members’ failings? ” 5.

Narrative Bias This describes peoples’ tendency to make sense of the world through stories. Our brains have to process a lot of information, so it creates a story to link different items. It also ignores facts that don’t fit the narrative.

TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “What story am I telling myself about this choice, event, or product? Have I ignored anything that might disprove this mental story? What happens if I turn this story on its head?

” 6. Survivorship Bias This describes the mental error of only concentrating on the projects or people that have been successful, and overlooking those that failed when analyzing what made something a success. A famous example of Survivorship Bias in action comes from military history.

During World War II, statistician Abraham Wald was working for the U. S. military to try and figure out where planes should have their armor reinforced, in order to avoid getting shot down.

The military’s initial efforts weren’t as successful as they’d like, and Wald knew why. The military had decided to only reinforce those areas where planes had been shot. But the problem was, they were only seeing planes that had returned.

In other words, where these planes had been hit was survivorable damage, because they’d flown home. The planes who’d crashed hadn’t returned and therefore hadn’t brought back data about the places where the damage proved fatal. Wald proposed that the military reinforce the areas where the surviving planes had not been shot, as those were the places where downed planes had been damaged.

Wald’s brilliant observation was correct, and saved many planes from a crash landing. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “When I look back to see what’s gone right, have I also looked at what’s gone wrong? Am I accounting for the features, tendencies or characteristics of failure as well as success?

What features or choices do success and failure have in common? ” 7. Anchoring This is the tendency for people to use the first piece of information they see to judge the following information.

For instance, if you see two bottles of wine — the first one you see costs $2000 and the second costs $200 — you’re less likely to think of the second bottle as expensive because you anchored to $2000 as the cost of a bottle of wine. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “In what context did I see this product and its price? Is the company making an effort to anchor me against something more expensive, to cloud my judgment?

” 8. Halo Effect This is the tendency for people to let one positive trait guide their total opinion of a person, product, or experience. For example, people consider good-looking individuals more intelligent, more successful, and more popular.

TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “What do I really like about this? ” then imagine it without that trait. Do you feel the same way?

Interrogate your feelings about this product, person, or experience. 9. Hyperbolic Discounting This is the tendency for people to value immediate rewards like sleeping in, over long-term rewards like being fit.

This means people have to outwit their own psychology in order to get in a workout or achieve other goals. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “What tends to win in my mind — the here and now or the long term benefits? Which is more important to me in the long run — comfort or this goal?

” Here’s a hint: Picture yourself in 10 years — are you better off for having prioritized the bigger picture? 10. Planning Fallacy This is the tendency for people to underestimate how much time it will take to complete a future task.

In other words, people aren’t realistic about their timelines. TO AVOID THIS BIAS, ASK YOURSELF: “How much time did this project take last time? Have I accounted for delays and setbacks that I can’t yet anticipate?

” An interesting feature of cognitive biases is that even if you’re aware of them, you still have to stay attentive to what biases might be driving your thinking. You can also follow a process like this one to help keep yourself vigilant: First, be aware of the common cognitive biases that exist (you’ve started that process with this video). Second, be attentive.

Pay attention and actively work to combat cognitive biases in your decision-making process. Last, question yourself. The “ask yourself” considerations in this video are a good place to start, but make sure you have a process in place to de-bias your thinking when making decisions.

Related Videos

14:11

If You Want To Charm People, Play The "Opp...

Charisma on Command

6,087,281 views

10:08

12 Cognitive Biases Explained - How to Thi...

Practical Psychology

2,211,315 views

12:21

6 Psychology Tricks To Make People Respect...

Charisma on Command

9,122,207 views

13:15

21 Tiny Habits to Improve Your Life

The Art of Improvement

4,685,532 views

17:59

The Paradox of Being a Good Person - Georg...

Pursuit of Wonder

2,041,002 views

28:28

Russell's Paradox - a simple explanation o...

Jeffrey Kaplan

8,029,352 views

11:31

HARVARD negotiators explain: How to get wh...

LITTLE BIT BETTER

1,985,051 views

5:16

How to make smart decisions more easily

TED-Ed

1,591,690 views

4:44

The Most Common Cognitive Bias

Veritasium

15,564,465 views

10:38

You’d Be Surprised How Smart (Or Dumb) You...

Pursuit of Wonder

1,343,487 views

4:21

The Dunning Kruger Effect

Sprouts

2,843,961 views

5:15

How to improve your daily decision making:...

Bite Size Psych

259,294 views

28:11

How to become 37.78 times better at anythi...

Escaping Ordinary (B.C Marx)

19,053,443 views

11:31

9 Mental Models You Can Use to Think Like ...

Farnam Street

325,432 views

21:37

20 Minutes on UnderstandMyself.com

Jordan B Peterson

1,047,371 views

24:27

30 cognitive biases & psychological misjud...

Progress Leaves Clues

42,208 views

3:49

Heuristics and biases in decision making, ...

Learn Liberty

622,070 views

6:15

Cognitive Biases 101, with Peter Baumann ...

Big Think

153,434 views

8:12

9 Cognitive Biases You Need to Avoid

Mind Known

51,827 views

12:22

3 kinds of bias that shape your worldview ...

TED

322,622 views