An introduction to Beamforming

60.67k views2300 WordsCopy TextShare

MATLAB

This video talks about how we actually have more control over the shape of the beam than just adding...

Video Transcript:

In the last video, we talked about how the combination of the array factor and the element pattern creates the array pattern. And often, we're trying to create a more directional beam with an array. Now, in this video, I want to talk about how we actually have more control over the shape of the beam than just adding additional elements or adjusting the position and orientation of those elements.

We can also adjust the gain of the signal to each element and apply phase unevenly to each element. And that gives us a lot more flexibility in beamforming. Plus, with the advances in fast analog-to-digital converters we can have full digital control over each individual element, which opens up the possibility of adaptive beamforming, which is pretty cool.

I'm Brian, and welcome to a Matlab Tech Talk. Before we get into beamforming, I first want to talk about why we might need more control over how we form the beam than what we just covered in the last video. I mean, we know we can form a really sharp beam with an array.

In general, the more elements in the array, the sharper the main lobe of the beam. And then, through phase shifting, the beam can be steered. However, forming the sharpest beam and then pointing it at the desired signal isn't the only thing we care about.

We care about the quality of the signal, and specifically how much signal we get compared to noise and interference. And the world is full of noise and interference. For example, interference can come from the signal itself reflecting off other surfaces and arriving at the array through multiple different paths.

Or interference can come from a secondary source. For example, in cellular applications, when trying to communicate with a single phone, interference can come from other nearby cell phones, or even other devices that operate in nearby bands. Or, with an array of microphones that are used to pick up sounds in one direction, interference can come from just other noises in the vicinity.

Now, regardless of the source, potentially we have signal in some direction that we want to maximize and interference in others that we want to minimize. And ideally, we would just point that sharp beam at the signal, and then, hopefully, the array gain in the direction of the interference would be low enough that the signal-to-noise plus interference ratio at the receiver is sufficient. Of course, this might not be the case because, remember, we have these side lobes.

Now, they have less gain than the main lobe, but a loud interference signal from that direction will still impact the received signal. So one thing that is often done is to try to reduce the side lobes. And this is where additional beamforming in the form of gain tapering can come into play.

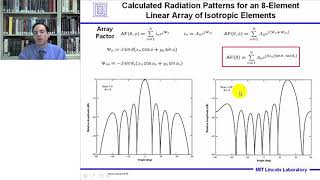

So let's talk about why that is the case. OK, so we know that this is the pattern for an eight-element isotropic linear array. And for this pattern, we are sending the exact same signal to each isotropic element.

And that means that each signal has the same power, which I've indicated here with these sliders. You can think of these as like volume sliders, where moving them up increases the volume or the gain, and then moving them down decreases the gain. So watch what happens when I lower the gain to just the two outside elements.

Notice that the pattern changes. The two lowest side lobes get smaller and then eventually disappear. In fact, by taking the power all the way down to zero like this, then we're just really left with a six-element array.

And then, by bringing the power back up, we are slowly transitioning back to an eight-element array with uniform gain. In this way, changing the gain to an element can affect the pattern, and it can affect it quite a bit. Here, I'm just cycling through random gains for each element.

And you can see how much the side lobes grow and shrink and change. Now, most of these random patterns are much worse than the original uniform gain, but here's what's interesting. Instead of just choosing any random gain, if we taper the gain to each element in a way that lowers the power to the edge elements but increases the power to the center elements, we can lower the gain of all of the side lobes.

I mean, check them out. They're much smaller now, and that's the power of, well, adjusting the power to each element. But it has come at a cost.

The main lobe is now wider than it was without tapering, and if I cycle back and forth between tapered and uniform gain, you can see that the side lobes shrink and grow, and the main beam is getting a little wider or a little narrower. So with tapered gains, we're trading the resolution of the radar for lower side lobe gain. Now, for older radar systems, tapering would be achieved using analog attenuators in line with each element, and they would be more or less fixed for a given array.

So you would pick a tapering strategy that would produce the pattern you need and then shift the phase to steer that pattern. So with that being said, let's look at phase. Here, I've added a second, blue slider that indicates how much phase shift is being added into each element signal.

And recall that by shifting the phase the same amount relative to the element before it, we can steer the beam. And phase shifting like this-- at least for narrowband systems-- could be achieved by delaying the signal to each element and then summing them all up-- a so-called "delay and sum" approach. But just like with gain, we aren't limited to regular spacing of phase shifts.

We can apply any arbitrary phase shift to each element separately. For example, these are a bunch of different random phase shifts. And so you can see how much this also affects the pattern.

And now that modern beam-scanning radar have full digital control over the signal to each element, both the phase and gain can be manipulated digitally, giving us the ability to pick any gain and any phase shift that we want to each element. But once again, most combinations of random gains and phases produce, probably, an undesired pattern. But the important thing here is that we have the capability of choosing these combinations, and that is powerful for beamforming.

Now, the way we define these gains and phases-- at least mathematically-- is with a weight vector. And to understand what this is, let's look at the gain and phase slider. Instead of a left, right, up, down slider system like I've drawn here, let's say we represent gain and phase on a complex plane with a phasor.

So here, a value of 1 plus 0j corresponds to a gain of 1, which is the length, and a phase of 0 degrees, which is the angle. So I can increase the gain to 1. 5 with this complex number.

And I could change the phase to pi radians, or any combination of these two. So now if we zoom back out, we have eight complex numbers representing the gain in phase for each of the elements in our array. And finally, these numbers all packaged together are the weights for the array.

They represent the unique gain and phase that is applied to each element. All right, cool, so we have this ability to form a beam through these weights. But the question is, how do we choose them?

Well, with a conventional beamformer, it's usually set up with a gain taper to control the side lobes, and then the phase is shifted to steer the beam-- exactly what I'm showing here. In this way, we form a sharp beam, and then we steer it towards the direction desired, regardless of what other interferences exist in the environment. But in contrast to the conventional approach, we can also use an optimization algorithm to adjust the weights based on the statistics of the received data.

That is, we can calculate the weights that will produce some optimal pattern given the actual environment. And this is adaptive beamforming. Now, I'm going to briefly introduce one particular algorithm for adaptive beamforming, which is MVDR.

But there are many others, and I've left links to some of them below if you'd like to learn more about different adaptive strategies. All right, so for this example, let's say that we have this eight-element linear array, like we've had this whole video, and there's a signal coming in from this direction, which the array is trying to pick up. So, obviously, we've pointed the highest-gain portion of the main lobe right at the signal.

But let's say that within the environment, there's another source coming from this direction that's producing some interference. The interference is right at the highest gain of one of the side lobes, and perhaps we want to do something about this. And we know that we can manipulate the shape of the pattern even further by adjusting both gain and phase.

So how can we adjust the weights to minimize this interference? Well, if all we're trying to do is minimize the total power in the received data, then the optimal gains are just zeros across the board. I mean, if nothing is getting through, then there is no interference, and the problem is solved.

Of course, that is a silly option. We're not just trying to optimize for lower interference. We also have a constraint in that we want to maintain the same gain in the direction of the signal.

That is, we want to minimize power variance but not distort the signal. And this is the idea behind the minimum variance distortionless response adaptive beamformer, or MVDR. With MVDR, we have to give the algorithm two things.

We need to give it the received signal at the array so that it has an idea of the total power that it's trying to minimize, and we have to tell it where we want a distortionless response. That is, we have to give it the angle of arrival for the signal so that it constrains the algorithm to maintain the gain in that direction. So this is a classic constrained optimization problem.

We want to optimize the weights such that the total received power is minimized, but with the constraint that power in the direction of the signal is maintained. And graphically, this is what we're looking for. We want to manipulate the weights in such a way that changes the gain everywhere except in the direction of the signal.

But the minimum variance part comes from the fact that we want the lowest total power at the receiver. Now, in this case, since the interference is only coming from a single direction, the lowest total power means dropping the gain in the direction of the interference only. All of the other directions don't contribute to the total power, since nothing is coming in from those angles.

So we actually have a lot of room to play with here. Now, I've linked to a page that walks through the details of the mathematics of this algorithm if you're curious. But for this video, I'm going to use MVDR Beamformer, which packages that optimization algorithm up into a simple Matlab function.

All right, so we need a few things for this function to work, like the environment, the direction of the signal, and the array specifics. And so to set the environment with the signal and the interference, I just loosely followed the example called "nulling with LCMV beamformer," which I've linked to below. In this example, we set up a signal from one direction and interference from another direction and build the received data.

And now, here is where I'm going to use that data to calculate the weights with this simple script. I'm creating an MVDR beamformer for my eight-element isotropic array, and I'm telling it the direction of the signal, which I know. And now, here's where I'm calculating the optimal gains given the received data, which has both the signal and the interference in it.

And this is the resulting weight matrix-- which, by the way, corresponds to these phases and these gains for each of the eight elements. And now, if I go back to our array pattern and put that weight matrix in, we can see the result. And as expected, there's a really deep null right at the interference.

Now, there is more gain in these other directions, but again, we don't care about that since there is no power coming in from that way. If we later find out that there is another interference source from those directions, well, we can just update the environment data and then rerun MVDR to find new optimal weights that will minimize all of the different interferences together. In this way, MVDR allows the beamformer to adapt to a changing environment.

All right, so that was a quick introduction to beamforming, and I recommend checking out the examples that I left links to in the description below if you want to learn more. In the next video, we're going to talk about some of the modern applications of beamforming and scanning arrays. So if you don't want to miss that or any other future Tech Talk videos, don't forget to subscribe to this channel.

Also, if you want to check out my channel, Control System Lectures, you can find more control theory topics there as well. Thanks for watching, and I'll see you next time.

Related Videos

13:15

Why multichannel beamforming is useful for...

MATLAB

25,265 views

15:53

Pulse waveform basics: Visualizing radar p...

MATLAB

39,500 views

16:08

Everything You Need to Know About Control ...

MATLAB

529,971 views

17:36

What Are Phased Arrays?

MATLAB

106,810 views

13:08

Why Digital Beamforming Is Useful for Radar

MATLAB

40,615 views

14:30

DIY sonar scanner (practical experiments)

bitluni

1,048,976 views

44:11

Multi-User MIMO Beamforming in 5G New Radio

MATLAB

11,246 views

10:01

A gentle introduction to beamforming

AudioLabsErlangen

21,542 views

18:13

FMCW Radar for Autonomous Vehicles | Under...

MATLAB

103,232 views

33:43

TSP #181 - Starlink Dish Phased Array Desi...

The Signal Path

141,183 views

16:17

Measuring Angles with FMCW Radar | Underst...

MATLAB

47,957 views

8:02

How does an Antenna work? | ICT #4

Lesics

7,581,308 views

26:27

Phased Array Antennas - An Introduction | ...

MIT Lincoln Laboratory

50,678 views

7:46

Basics of Antennas and Beamforming

Wireless Future

278,636 views

33:25

TSP #236 - A 77GHz Automotive Radar Module...

The Signal Path

92,679 views

18:08

The Radar Equation | Understanding Radar P...

MATLAB

44,554 views

![Beamforming directivity [Part 1, Fundamentals of mmWave communication]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/WOE_nKBKUsE/mqdefault.jpg)

11:01

Beamforming directivity [Part 1, Fundament...

Wireless Future

13,051 views

37:32

An Introduction to Direction Finding

Rohde Schwarz

93,937 views

39:13

Introduction to Radar Systems – Lecture 1 ...

MIT Lincoln Laboratory

247,619 views

23:40

A Detailed Introduction to Beamforming

5G Learning

112,222 views