How did the Reconquista Actually Happen?

830.06k views1526 WordsCopy TextShare

Knowledgia

How did the Reconquista Actually Happen?

While many people are aware of Iberia’s religious history...

Video Transcript:

The Reconquista. Or, as it’s known in English, the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. While many people are aware of Iberia’s religious history including the infamous Spanish Inquisitions, not so many are aware that neither Spain nor Portugal was always controlled by Christian Europeans.

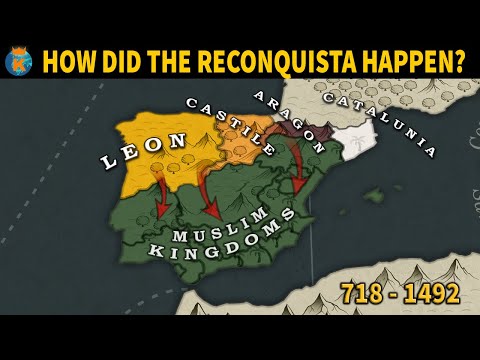

In fact, there was a period of almost 8 centuries that marked a tireless power struggle between the Christian Kingdoms and Muslim Caliphates. This stretch began after the Umayyad Caliphate launched their conquest of Hispania in 711 that would destroy the local Visigothic Kingdom and soon put massive pressure on the neighboring Kingdom of Asturia. It wasn’t long before the Europeans took great umbrage to these acts, and only about a decade after the Muslims first stepped foot on the peninsula for conquest, the Christians were ready for the Reconquista… The first event of this centuries-long campaign is generally believed to be the Battle of Covadonga in which Pelagius the Visigoth led a continued rebellion straight into the belly of the beast at the Picos de Europa.

. . The Umayyads were returning from an unsuccessful clash with the Franks over in France and decided that, in order to rejuvenate morale, it was time to crush the revolt that had been brewing in the Kingdom of Asturia.

Unfortunately for the Muslim conquerors, Pelagius was unwavering and the Asturian rebels routed the Umayyads, forcing the latter to retreat and subsequently triggering the Christian crusader spirit throughout the region. Still, the following centuries represented a slow period in the reconquest. The Muslim Caliphate was focused on consolidating its power from the capital in Cordoba, while the ousted Christians were not quite ready enough to launch a full-scale campaign to reassert their claims to the peninsula.

Additionally, there were other matters that would need to be worked out such as who would take which territories. In the meantime, the young Kingdom of Asturia was slowly expanding its own claims through subtle victories, such as in 924 when the Asturians even managed to seize the city of Leon. There were a couple of centuries of planning, infighting, and overall instability, but when the 11th century rolled around, the Christians were finally fully ready… The Kingdom of Asturia was no longer the only growing Christian state within Iberia’s borders.

The kingdoms of Castile, Leon, Catalonia, and Navarre were one by one joining the Reconquista cause, and in 1085, the old Visigoth capital of Toledo, which had now been under the control of one of the new Muslim Taifa kingdoms, fell to the Kingdom of Castile thanks to the efforts of King Alfonso VI. This was expected to set off an even greater level of morale and fighting spirit for the Christians, but instead, their efforts were shortly stunted. The Muslims, who had quickly realized what a threat the European Christians were becoming, called in Islamic warriors from Africa known as the Almoravids.

These warriors were fierce and fought valiantly for the Muslims of Iberia, but the Christians continued their struggle nonetheless. As the Spanish kingdoms focused on their portion of the peninsula, fighting both the Muslims and each other, over in Portugal came maybe the greatest victory yet. On June 24, 1128, the Battle of Sao Mamede between Afonso Henriques of Portugal and his own mother, Teresa, resulted in the declaration of an independent Kingdom of Portugal with Afonso on its throne.

In 1143, the Kingdom of Leon recognized Afonso as the true King of Portugal and in 1179 the Pope did the same. This was a hugely significant achievement for the Christians of the peninsula and the further expansion in the Algarve in the next century consolidated this victory even more. Part of this success may be attributed to the instability within the Muslim portion of the peninsula.

The Almoravids had faired pretty well when they first accepted the invitation to invade, but in the 12th century, they too fell as the Almohads, not even the Christians, defeated them. Shortly after, in 1212, a united force of the Christian kingdoms crushed the numerically superior Almohads, clearing the way for the Reconquista to continue on… Previously, Alfonso II of Aragon and Alfonso The Eighth of Castile had come to an agreement concerning who could lay claim to what Muslim-occupied territories with the Pact of Cazorla, which had significantly helped to prevent infighting from slowing down the reconquest. Now, following the triumph at Las Navas de Tolosa against the Almohads, the new king of Castile and Leon, Ferdinand III, united his lands and launched a new campaign to retake the rest of the Muslim territories for his newly expanded kingdom.

Cordoba fell in 1236, which was a severe blow to the Muslims, and other important cities followed. By 1250, almost all of the Iberian Peninsula was back in Christian hands, aside from the Muslim Kingdom of Granada which existed under Castillian suzerainty thanks to the evolved policies of Ferdinand III, who had originally tried to expel all Muslims from his recaptured lands but quickly realized the economic consequences of such a strategy. Instead, the Kingdom of Granada was allowed to remain Muslim under the condition that tribute was paid annually to the Castilian king.

This nevertheless led to a period of growth for Islam in Spain and the next King of Castile, Alfonso X, decided to set up the Escuela de Traductores in Toledo which would translate Arab literature for the Europeans to understand. Meanwhile, James I of Aragon and Alfonso III of Portugal were expanding their own borders and bringing the rest of the Iberian Peninsula back under Christian hegemony. It appears that for the time being, the Christians had accepted the Reconquista as complete and were satisfied with allowing the Muslims to stay in these circumstances.

This, though, would soon change… Of course, throughout the final period of rapid Christian expansion, the Muslims didn’t go down without a fight. Small skirmishes and battles would break out from time to time, but the Battle of Rio Salado marked the final major clash as the Portuguese and Castilians routed their opponents. After another century of victorious consolidation, the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were joined by the wedding of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in 1469 and became known now as the Catholic Monarchy.

Apparently, these monarchs were not quite as tolerant as the previous leadership and decided to crack down on the Kingdom of Granada once and for all. In 1491, the newly combined forces of Castile and Aragon laid siege to Granada in an attempt to annihilate the only remaining Muslim stronghold in the peninsula. The Muslims tried to fight back for some months, but Prince Boabdil of Granada soon realized that there was no way he could defeat the attackers on his own.

So, the monarch somehow managed to negotiate a truce with his Spanish opponents through the promise of surrender in the case that he was unable to get support from a fellow Muslim state after 4 months. The allies that Boabdil reached out to, the Marinids of Morocco, never sent aid and after 4 months, as agreed, the truce expired and Prince Boabdil surrendered himself and his kingdom to the Catholic Monarchs on January 2, 1492… For many Christians, this victory and the final collapse of Islam within the Iberian Peninsula represented some type of distant redemption for the events of 1453 that brought about the Fall of Constantinople and the devastating destruction of the Byzantine Empire. Religion also seemed heavily significant even after the reconquest was finished, and the following Alhambra Decree even went as far as banishing all practicing Jews from the Catholic Monarchy, and later both the territories of Castille and Aragon would have mandatory conversions to Catholicism for any Jews or Muslims under the crown.

The following Spanish Inquisition continued this harsh legacy of the Reconquista and even today, many Iberian Christians celebrate the fall of Granada as a great victory for their nations. So, to summarize, the Reconquista was more than just a single war or campaign. More accurately, it was a series of campaigns and clashes between the Muslims and Christian of the Iberian Peninsula as the latter worked unrelentingly to regain their territory and authority.

The reason why the reconquest took nearly 8 centuries is due to a combination of challenges faced by the Christian Europeans. For one, repetitive infighting between the Spanish and Portuguese states and kingdoms greatly held up and sometimes weakened their overall cause. Additionally, the help called in by the Muslims from Africa proved to put a remarkable damper on the Reconquista efforts and overall speed of progress.

Although civil war amongst the Muslims did give aid to the Christians at times, their own internal and external issues were not always simple enough to set aside. And lastly, the decision to leave the Kingdom of Granada alone for some time also delayed the final end to the reconquest journey.

Related Videos

10:34

What happened with the Muslim Majority of ...

Knowledgia

2,154,160 views

5:42

Ugly History: The Spanish Inquisition - Ka...

TED-Ed

1,561,174 views

31:53

Battle of Aljubarrota, 1385 ⚔ How a peasan...

HistoryMarche

963,941 views

18:19

Why wasn't Portugal Conquered by Spain?

Knowledgia

1,199,485 views

23:52

The Bronze Age Collapse (approximately 120...

Historia Civilis

4,107,424 views

23:21

Battle of Sagrajas, 1086 - An ambush that ...

HistoryMarche

245,692 views

26:09

An Epic History of the First Crusade (All ...

Epic History

3,750,872 views

14:46

Why did the Spanish Empire collapse?

Knowledgia

1,845,355 views

14:47

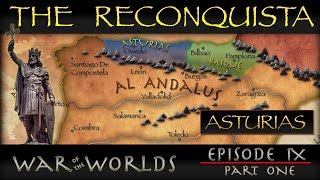

The Reconquista - Part 1 History of Asturias

Flash Point History

92,594 views

23:22

Why did The Confederates Lose The War in j...

Knowledgia

428,777 views

16:27

Batalla de las Navas de Tolosa, 1212 ⚔️ ¿P...

Historia ex Hispania

114,050 views

18:57

Spanish Inquisition: Basics - Medieval Rel...

Kings and Generals

230,391 views

15:32

Why 70% of Spain is Empty

RealLifeLore

11,506,744 views

9:22

The Animated History of Spain

Suibhne

3,056,926 views

9:26

Why did the Caliphate of Cordoba Collapse?

Knowledgia

480,742 views

15:08

Battle of Guadalete, 711 AD ⚔ How was Spai...

HistoryMarche

334,948 views

50:09

The Visigoths and the Arab Conquest of Spa...

Real Crusades History

207,788 views

11:16

Why did The Anglo Saxons Migrate to Britain?

Knowledgia

719,332 views

3:42

The Reconquista: Every Year

Ollie Bye

1,662,910 views

11:39

Why did Spain give up Gibraltar?

Knowledgia

520,856 views