The Worst Disasters in History

626.07k views4779 WordsCopy TextShare

Scary Interesting

Hello everyone and welcome back to Scary Interesting and to some of the Worst Disasters in History. ...

Video Transcript:

Hello everyone, and welcome back to Scary Interesting, and to some of The Worst Disasters in History. As a warning, the second disaster in today's video is so disturbing and so gruesome, that it led to radical and sweeping changes across an entire industry. And so, although the events are fleeting and non-descriptive, they are still highly disturbing, so viewer discretion is strongly advised.

[intro music] Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley was once a powerhouse of energy production for the United States. Thanks to the area's massive deposit of anthracite, which is a type of coal up to six times more valuable than regular coal, the Wyoming Valley played a significant role during the American Industrial Revolution. And due to this and other factors, it saw a wealth of success during World War I as the employment rate skyrocketed with the need for coal increasing.

But unfortunately, this boom wouldn't last indefinitely as alternative fuel sources started to enter the marketplace. By the time World War II began in 1939, the demand for anthracite wasn't nearly what it once was, and while most blue-collar industries raked in money as they supported the American war effort, the Wyoming Valley was very much in decline. And obviously, things didn't get any better after the war ended, as unemployment rates for the region were some of the highest anywhere in the nation.

The industry held on as best as it could, and many mines in the area were still operational by the late 1950s. However, conditions and ethics were sketchy at best, as the companies that owned the mines pushed to produce as much anthracite as possible. This was an approach that would lead to disaster at the Knox Mine in Pittston on January 22nd, 1959.

That morning, around 81 miners living in a three-county Wyoming Valley, got up and got ready for work. 41-year-old Frank Orlowski, who worked in the mines much of his adult life, began his morning routine, which usually consisted of enjoying a cup of coffee while reading the newspaper before heading out. He never usually ate breakfast, but that morning, he said he was hungry, so his wife made him a bowl of cereal before she packed a few extra sandwiches in his lunch pail.

Elsewhere, Samuel Altieri always rode the bus with his wife together in the mornings, as the stops for their respective jobs were along the same route. After saying goodbye to his wife, she got off the bus to begin her work shift at the Pittston Apparel Company, and the two went their separate ways. When surveyor, Joseph Stella, got to work, he entered the Knox Mine with plans to inspect some of the worksites.

It had been a week or two since he performed a routine inspection on some of the mine's miles of underground tunnels, so he entered the main shaft of the river slope section and began heading toward where several crews were working. He then reached one of the worksites and checked that everything was as it should be before turning around in the direction of another worksite. Just as he was making his way down another one of the mine's many corridors, he heard one of the miners from behind, shouting to get out of the mine.

When John turned around, he then saw Samuel and several of the other miners running behind him. He and some other miners then rounded up the rest of the men and started making their way toward the main shaft. And before long, they noticed something under their feet.

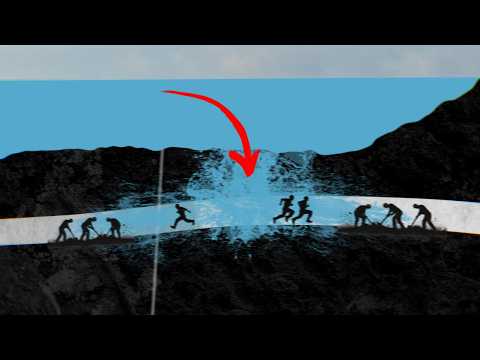

It was water, and it was rising fast. Now, the Knox Mine was an elaborate maze of tunnels that was as deep as a thousand feet, or 305 meters beneath the surface. But part of the mine, particularly the river slope section, ran directly under the Susquehanna River, so the mine operators always had to be mindful not to dig too close to the riverbed.

On that day though, one of the crews neglected to drill boreholes to gauge how thick the rock ceiling was. At the very minimum, 35 feet, or 11 meters, was considered safe to dig to, but something had gone very wrong. Digging in the section went much too close to the riverbed, and the roof collapsed, causing millions of gallons of water to come rushing into the mine in an instant.

It just so happened also that the Susquehanna River was experiencing one of the worst floods in recent memory at the time due to heavy rains earlier in the week. As water gushed into the mine, the surface of the river just above the 75 foot, or 23 meter-wide hole, began swirling, and a violent whirlpool formed, sucking down flood debris and huge chunks of ice that had formed in the river. So before long, their run toward the main shaft turned into a trudge through waist-deep water that was rapidly rising.

As the torrent continued to flood the tunnels, seven of the men spent the next five hours in frigid river water, only escaping after climbing hundreds of feet up an air shaft they discovered further upstream. Elsewhere, seven hours after the water began pouring into the mine, another group of 26 survivors was found wading through the flooded tunnels and led to safety. As more and more of those who managed to escape gathered outside the mine, it became apparent that 12 miners were missing, and if they survived at all, they were likely trapped.

Around this time as well, at least 28 men were taken to local hospitals with various injuries. At 3:15 that afternoon, and as all hell was breaking loose at the mine, Samuel's wife waited on the corner outside her workplace as the bus pulled up. Normally, she'd board the bus and be greeted by her husband's face smiling back at her from their usual seats, but this time, Samuel wasn't there.

Initially, she didn't pay it much mind because he would sometimes get a ride home from work from one of his fellow miners, but she quickly learned that something was terribly wrong when a woman on the bus turned to her and asked her if she heard about the accident at the Knox Mine. As terrifying as this news was to hear, she knew that because Samuel was an electrician, he wasn't always required to be in the mine, so she'd hoped she'd find him already home when she arrived. When that wasn't the case and the hours ticked by without any sign of him, she made her way to the mine only to be met with a large crowd of gathering townspeople.

In the crowd, she found several other miners, clearly soaking wet and exhausted from what they'd endured to escape, and they assured her that Samuel got out because they saw him. He had apparently posted up in one of the tunnels and was helping point the passing men towards safety and doing his best to keep everyone calm. While she was still trying to process everything that was going on, a frantic effort to stop the flood was underway.

In order to do that, the hole would have to be plugged up, but there was no way to access it from inside the flooding mine. The only way to stop the water was to plug the hole from the river itself. Officials needed to use the whirlpool to their advantage since it was pulling the entire river toward it.

Soon enough they started dumping mine cars, railroad cars, bales of hay, and piles of scrap wood into the swirling waters, hoping that by piling up this type of debris, it would plug the hole. So by nightfall, more than 30 coal gondolas and hundreds of bales of hay had been tossed into the whirlpool, but incredibly, its strength wasn't letting up. This effort continued throughout the night and into the next day, and since the Knox Mine had connection points to the other mines in the Wyoming Valley, 11 operations were suddenly closed for the foreseeable future, putting about 10,000 miners out of work.

Afterward, those who could assisted in the effort to plug the gaping hole in the riverbed, and by midday, the Lehigh Valley Railroad began building a road alongside its tracks to give trucks better access to the whirlpool, which sat about 20 yards from the swollen riverbank. Then by the end of the day, 38 more gondola cars, 200 mine cars, and truckloads of the largest rocks that could be gathered, were dumped into the river, as well as utility poles, railroad ties, and any other bulky debris rescuers could find. During a press briefing around this time, mine officials reported they believed that they had slowed the flow of water into the mine by about 30–35%.

They also expressed hope that the 12 men that were missing had found higher ground, but as time went on, a tragic picture started to come together. A miner who refused to be named in newspaper articles, told reporters that he had personally witnessed three bodies swirling in the floodwaters inside the mine's tunnels. And even more ominously, water measurements were taken at different shafts in the area.

At the No. 14 Coal Company shaft, about a mile south of the Knox Mine, the water had reached a depth of 325 feet, or 99 meters. And at the closer Hoyt Shaft, the water had risen to 500 feet, or 152 meters.

This did not bode well for the survival conditions of the missing miners. If the water was that high at the connecting mines, it was a strong indication that the Knox Mine was almost completely flooded out by that point. On January 25th, a scathing report appeared in a local newspaper about how the wives of the missing miners had been treated by the mining company.

Not only had the women not slept in two nights since the flood occurred, but they were also furious. All of them had gathered together, and the company officials knew where the women were holding vigil, yet no one from the company met with them or even told them that their husbands were among the missing. The names of the 12 missing miners were printed in newspapers and released to radio stations, and until that point, the only way they could have known that their loved ones were possibly victims of the flood, was through them not showing up at home.

One of the wives of the missing even said that they lived about a 10-minute walk from the mine, and her husband always followed the same routine after work. He'd come home, have a beer, and then take a bath. When she came home from her work day, she discovered the house empty and the beer in the refrigerator untouched.

It wasn't until she learned of the flood by word of mouth that she connected the dots. Later that day, another press briefing was held, and the Knox mining company officials had several big updates to share. After three days of pouring anything they could into the river to stop the flood, they had finally managed to plug the hole.

With that said though, they had very little hope that any of the men who were missing, could still be alive inside. The mine superintendent even went as far as to tell the media that there were no high points that were above the water line inside. And once again, this was also news that the loved ones of the missing men had to learn through reporters.

Around noon on January 26th, pumps that had arrived at site were set to be switched on, but there was an unexpected delay. Word of the disaster had caused many people from nearby towns and even out of state to flock to the Wyoming Valley. With the number of cars far exceeding the number of parking spots, people simply began abandoning their cars in the middle of city streets, which impeded efforts to get pumping underway.

It would end up taking more than 100 police officers to sort out the mess and clear the way for army engineers and navy consultants to reach the scene and begin the pumping effort. And obviously, time was of the essence as the missing men, if alive, had been trapped for four days. Unfortunately though, this would prove to be an insignificant delay.

Pumping took place around the clock for four more days, and the water level inside the mine only dropped about four or five feet, or less than two meters. On January 29th, pumps with the ability to remove up to 133,000 gallons of water a minute arrived at the mine, but there was more bad news. Estimates of how much river water had spilled into the mine were up to 40 billion gallons.

The Pennsylvania State Secretary of Mines even said that it would likely take upwards of three weeks or more to reach the miners. In fact, he believed that it would take another week or two just to reduce the water level by a hundred feet. And so, hope that the missing men would be found alive, was all but crushed by the news.

Pumping continued despite the tragic developments, but on February 10th, the effort suffered a setback as water started leaking back into the mine from the Susquehanna. By then, any reports in the mine had presumed that all the missing men were dead. Despite the efforts to pump the mine free of water, the bodies of the 12 men were never found.

Frank and Samuel were among the dead. An inquiry into the disaster got underway, and it was determined that the flood occurred as a result of illegal mining practices by the Knox mining company. Workers were advised to dig closer to the riverbed than was safe, which ultimately caused the ceiling to fail and billions of gallons of water to begin pouring in.

Ten mine officials would go on to be indicted, and six of them would serve jail time for their roles in the disaster. Sadly, the poor treatment of the widows would continue as the wives of the 12 victims wouldn't receive death benefits for more than four years after the tragedy. Some mining still occurs in the Wyoming Valley today, but the effects of the Knox Mine disaster are still felt as residents are reluctant to support new energy industries in the area.

In the predawn hours of December 18th, 1867, residents and visitors alike in the city of Cleveland, Ohio were starting their day. Just one week before Christmas, many were preparing for a holiday season that would include travel, which was something that had been much more difficult just a few years earlier. The US was still recovering from the Civil War which claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands.

But by 1867, things were starting to settle into a new normal, and the Christmas season was an opportunity to get back to family traditions. Many of those just waking up had tickets for the 6:40 AM Lakeshore Express train bound for Buffalo, New York, and were making their final preparations before heading to Cleveland's Union Station. And while some were travelling for pleasure, others were trying to squeeze in a last bit of business before the holidays.

Like, for example, one couple had just opened a general store in a small town in Pennsylvania and were going to Buffalo to purchase stock. Another couple had just gotten married, and they were travelling for a holiday season honeymoon. Another passenger was on his way to New York City to check on the east coast operations of his business, but he also planned to visit family and friends he had in the area during the trip.

That man was 28-year-old John D. Rockefeller of the famed Rockefeller family. John was a shrewd and disciplined businessman who meticulously managed to schedule down to the minute, but for some reason, on the morning of December 18th, he woke up late.

Upon realizing this, John quickly packed away the final items he planned to take with him, including wrapped gifts he planned to give to family and friends, and he had his luggage sent to head to the train station while he finished getting himself ready to leave. The weather that morning was typical for the shores of Lake Erie for that time of year. The temperature was brisk, and there was snow and ice in the ground, but the sun would be shining all day, making for clear and pristine travel conditions.

For unknown reasons, however, the Lakeshore Express was running behind that morning. Its departure time of 6:40 AM came and went with the train still idling at the station, which was lucky for John as his luggage finally arrived and was placed into one of the baggage cars. However, unfortunately, this still wasn't enough time for John, and when he finally showed up at Union Station, the Lakeshore Express was already several minutes into the journey, leaving him behind in Cleveland.

Now, while it was an express train, the Lakeshore would make several planned stops that day. The route itself hugged the eastern coast of Lake Erie, with the tracks barely veering more than a few miles off the shore, hence the route's name. From Cleveland, the train would travel to the northeast, spending somewhere around the first 70 miles in Ohio before crossing over the border into Pennsylvania.

It would then continue through the city of Erie, Pennsylvania, on its way to Western New York, where the majority of the mileage was. From front to back, the train was also made up of one locomotive, four baggage cars, and four passenger cars— the last three of which were first-class. Each passenger car also held about 50 people, and top to bottom, they were constructed mostly of wood.

As the trip wore on and the morning became early afternoon, the Lakeshore Express found itself close to three hours behind schedule due to its late start. To make up for this, it ran right around its maximum speed of 28 miles per hour, or 45 kilometers per hour. This was a safe pace for the clear, beautiful day it was.

Now, the train was initially scheduled to reach the station in Buffalo by 1:30, but it was looking more and more like its arrival was going to be closer to 4:30, if not later. This meant that those planning to get on the train at stations along the way, were forced to wait much longer than anticipated. On a platform in the small New York town of Brocton, this was of little concern to 39-year-old wood dealer, Benjamin Betts.

As he waited at the Brocton platform, he met another businessman and the pair became fast friends, so much so that they had lunch together while they waited for the delayed train. The two continued to pass the time with conversation until around 2:20 PM, when the Lakeshore Express finally appeared in the distance and began to slow ahead of the Brocton station. When it stopped, Benjamin and his new friend would have to part ways, with Benjamin having a second-class ticket, and the other man having a first-class seat.

After saying their goodbyes, the man with the first-class ticket walked his way to the very last passenger car and boarded, while Benjamin headed to second-class. This car was the first of four passenger cars that made up the end of the train. Soon after boarding, the Lakeshore Express pulled out of Brocton and headed for Dunkirk where it stopped for about 10 minutes to take on more passengers.

Not far ahead, it stopped again at Silver Creek, this time to load up on water and wood which took a relatively short time. At 2:49 PM, the Silver Creek telegraph operator tapped out a message to the daytime railroad agent in Angola, New York, that the express was heading his way. And before long, the Angola agent spotted the train, and soon after it passed, it approached a 160-foot-long bridge made of wood and concrete that sat above the Big Sister Creek, which is a waterway located at the bottom of a steep gorge.

As it began to cross the railroad bridge at around 3:11 PM, Benjamin noticed something strange from his second-class seat. The train started shaking, and suddenly, the brakes were applied, and the friction against the tracks let out a loud squeal that echoed throughout the gorge. To Benjamin, who was no stranger to train travel, the feeling was almost like some of the cars had disconnected; but from the second-class car, he had no idea of the type of devastation that was occurring in the back of the train.

As the express was making its way toward the bridge, it passed over what's called a frog, which is a crossing point of two separate tracks. When it did, the track crossing dislodged one of the wheels of the last car, causing it to start wobbling side to side over the gorge as the train continued to barrel forward. Then, just 21 feet, or about 6 meters ahead of the frog, was a railroad spike that was jutting out of its place, and the express ran right over it, further unbalancing the last car and causing it to jump the tracks.

It was at that moment that the last two cars decoupled from the rest of the train, quickly throwing passengers inside, into chaos. Nearly everyone then leapt from their seats and tried to make their way forward to the front of the train, but the wobbling and shaking was so violent that they were tossed around the inside of the car. Some people ended up trampled in the panic which would only grow as the end car tipped off the bridge and then began tumbling down into the gorge.

The second to last car remained in the tracks for a few more feet and appeared like it might make it all the way across the bridge, but it also derailed right as it was crossing its way onto firm land and slid down the gorge embankment. As the two cars rolled, the passengers inside continued to be thrown about. And making matters even more harrowing, the cars had large stoves that kept the passengers warm, and as they tumbled, so did the stoves.

And as they did, they spewed out hot coals everywhere, which burned passengers, and worse, set some on fire. The cars then came to a rest just a few yards away from one another and almost immediately burst into flames, as a result of the coals coming in contact with the kerosene gas from the lamps burning inside. Much of the wood that made up the car's construction turned into splinters as well on impact, further fueling the flames.

When his car came to a stop, Benjamin bolted from his seat, hopped off the second-class car, and began making his way down the steep, rocky, and icy gorge embankment, along with other brave passengers. Villagers from Angola also rushed to the scene to assist, having heard the loud squeal of the train's brakes and the impact of the cars at the bottom of the gorge. When Benjamin reached the gorge floor, he ran over to what remained of the last car as the fire continued to consume it.

And inside, he saw a man crying for help, and just behind him was his friend from the Brocton station. Reaching inside, Benjamin pulled out the first man, who was badly burned with what remained of his clothes, smoldering and smoking. He handed the man off to rescuers and turned back to get his friend out, but by the time he peered back inside the car, it was too late.

His friend was completely consumed. For the first five minutes after the derailment, the sound of those inside the train, echoed throughout the gorge. As the minutes ticked by, however, the panicked pleas for help became quieter and quieter, until the only sound in the gorge was the crackling of the fire eating up the wood splinters of the cars.

And horrifyingly, even all the way back in the village of Angola, residents reported the smell of burning in the air. Many of those who came to help in the rescue did what they could, but the cars burned so hot that even the bravest among them were driven back. When the sounds finally stopped, there was little more that anyone could do but wait until the flames died down so the process of recovery could begin.

As it did, a full picture of the tragedy in Angola began to unfold. The very few who managed to survive in the final two cars escaped with massive and significant injuries, including broken bones and serious burns. In fact, in the final car, only 3 of the 50 people on board survived the accident.

In addition, the coroner and a team of police, firemen, and doctors struggled to sort out the dead. Most of them were so badly burned that it was difficult to determine where one person stopped and another began. An unknown number of passengers also died from the impact with the gorge floor as the recovery team found a mass of furniture and bodies compressed and tangled together at the end of one of the cars.

Some time later, as night fell and the wreckage in the gorge smoked, another train pulled into the station in Angola and came to a stop. Aboard it was John who was forced to take a later train because he missed the morning Lakeshore Express. When he learned of what happened just a few feet ahead, he looked at his ticket from the morning train.

He was slated to sit in the train's final car. As the days passed and the bodies were gathered, those who could be identified were removed from the wreckage and handed over to mourning and traumatized families for burial. The unidentified were then placed into wooden crates, sometimes more than one per crate, and taken to Buffalo on a funeral train.

Several buildings in Buffalo then served as a temporary morgue as each of them were laid out so that family members could walk through and identify their loved ones. Like, for example, the couple on their honeymoon were identified a week after the accident occurred when their luggage claim tickets were discovered on them. Also among the dead were the couple that opened a general store, a newspaper editor, and even the railroad's president who was sitting in the last car.

Beyond those though, further identification was hampered by the train not keeping a passenger list. And even the total number of past individuals is in question, but it's generally agreed that at least 50 people lost their lives in the accident. And of those, 19 were never identified and were buried together in a Buffalo cemetery, although that number is also the source of controversy.

In the aftermath, reports of what happened spread nationwide, and newspapers around the country dubbed the accident "The Angola Horror", which is a name still synonymous with tragedy today. And because of public outcry, the incident was the impetus for several significant changes to the railroad industry. Wooden cars were banned, causing every train in the country to replace theirs with cars made of iron.

Better braking systems were also invented and deployed. Wood-burning stoves in passenger cars were also bolted to the floor to prevent them from tumbling in the case of derailment. And finally, track gauges also became standardized.

Up to that point, different tracks had different gauges, which was believed to be a contributing factor in The Angola Horror. And saved by the one rare instance of running late, John would go on to form the Standard Oil company and later began selling products meant to make railroads safer. Benjamin, meanwhile, left the wood-dealing business and became an engineer who contributed greatly to modern bridge design and safety.

If you made it this far, thanks so much for watching. If you want to listen to the audio-only version of these videos, you can listen wherever you listen to podcasts. If you want to support the channel, consider joining the Patreon or becoming a channel member here on YouTube.

Also, if you have a story suggestion, feel free to submit it to the form found in the description, and hopefully, I will see you in the next one.

Related Videos

23:39

The Worst Disasters in History

Scary Interesting

688,646 views

16:57

What Happened To The Nautilus?

Mustard

13,818,054 views

1:23:35

OFFSHORE NIGHTMARE: The Collapse of Texas ...

Brick Immortar

930,433 views

1:55:27

Worst Fails of the Year | Try Not to Laugh 💩

FailArmy

2,179,419 views

3:22:17

3 Hours Of WW2 Facts To Fall Asleep To

Timeline - World History Documentaries

1,624,443 views

20:32

The Braamfontein Explosion

Into the Shadows

508,612 views

17:58

The Worst Place to Be Stranded on a Mountain

Scary Interesting

184,944 views

1:09:09

The Enduring Mystery of Jack the Ripper

LEMMiNO

12,684,906 views

1:34:02

7 Worst Disasters That Were EASY to Prevent

Dark Records

1,605,475 views

23:57

The Worst Disasters In History | Part 3

Scary Interesting

676,945 views

7:45

Star Trek Discovery Dies... To Thunderous ...

The Critical Drinker

493,657 views

3:30:57

The Full History of Douglas Aircraft - Spe...

Rex's Hangar

650,022 views

2:01:18

Half-Life 2: 20th Anniversary Documentary

Valve

5,143,440 views

26:04

A Collection of Horrible Fates

Scary Interesting

315,372 views

17:55

The Terrifying Deepest Ocean Stranding in ...

Scary Interesting

463,878 views

23:42

The Worst Disasters in History

Scary Interesting

598,430 views

1:49:07

Exciting Quests from the World of Matchbox...

Hot Wheels

4,804,951 views

18:04

The $842,000,000 Salvage of Golden Ray

Waterline Stories

133,821 views

3:03:29

101 Interesting Facts to Fuel Your Next Co...

BRIGHT SIDE

251,832 views

21:36

Why The UK Never Made Another Harrier Jet

The Military Show

790,628 views