Making uranium glass

13.34M views5504 WordsCopy TextShare

NileRed

Visit https://Brilliant.org/NileRed to get 20% off a year of Brilliant Premium!

For this project, ...

Video Transcript:

This video has been sponsored by Brilliant. Sometime last year was the first time that I heard about uranium glass, and I thought that it was some marketing thing or something, but it's actually real. It's not glass made entirely out of uranium, but it is glass with uranium in it.

This got me really interested in it and I decided to buy some, and I got this cup of it off eBay. Pure uranium glass is normally yellow, but this one is green, and I think it's because they put some iron into it. Regardless of that, that's not really what makes uranium glass special, and it's what it looks like under a black light.

The uranium in it fluoresces, and it makes this really nice green color. The actual amount of uranium in it is quite small, so the glass itself is only minorly radioactive. General glassware and cups like this, were super popular in the late 1800s and the early 1900s.

However, during World War II, the government started confiscating all the uranium and diverting it to nuclear research. This killed the entire industry for uranium glass, until the late '50s, when some restrictions on uranium were lifted. A few companies started making it again, but at that point, the health effects of radiation were a lot more well-known.

Also after the nuclear bombs, the public perception of uranium wasn't exactly great. Nowadays, there are apparently still a few companies that make it, but I wasn't able to find any of it for sale. As far as I know, if you want to get some uranium glass, you really can only buy the old stuff.

I found this all really interesting, and I've been wanting to work with uranium for a while, so I decided to make some uranium glass. My original plan was to buy some uranium ore, and then refine it, and use that purified uranium, to put into some glass. However, I learned from Cody over at Cody'sLab, that the government doesn't really like it when you show how to refine uranium on the internet.

Instead, I had to start with an already purified source, and I was able to find some depleted uranium. This means that it's missing the isotope to do things like generate nuclear power or make nuclear weapons. However, it's still good for making glass.

Uranyl nitrate is the nitrate salt of uranium, and when it's pure, it can form these nice yellow crystals. Besides just looking pretty, it seems relatively mundane, and that's something that I've always found interesting about radiation. As this uranyl nitrate just sits there, it's shooting off thousands of extremely small particles, but they're way too small to see or to feel.

There's no way to naturally perceive that it's there, and this was one of the biggest reasons why it took so long to discover radiation. To know that it's there, it has to be detected using some instrument or setup, and over the years, many different methods have been developed. Nowadays, one of the easiest ways is to just use a Geiger counter.

But before starting this project, I didn't have one. However, when working with something radioactive like uranium, it's pretty much absolutely necessary. I looked around online, and I ended up getting this one off Amazon, which wasn't very expensive, but it was supposed to be decent.

I turned it on and I let it stabilize for a minute, and I saw that the natural background radiation was about 15 cpm. Cpm stands for counts per minute, and it's a reading of how many radioactive particles it detects over a minute. Radiation exists everywhere in the environment, and you're always being bombarded by it naturally, and this reading of 15 cpm is actually quite low.

It was time to test it with the uranium, so I just put it next to it. There was clearly an effect, and this Geiger counter was going to be more than usable for this project, but it unfortunately wasn't going to be super accurate. This was because most of the radiation that's let off by uranium is in the form of something called alpha particles, and this counter is not even able to detect them.

It's only able to pick up the beta and the gamma rays that it's letting off, which are significantly less than the alpha. Despite this, it's still going to be really useful because I don't actually need a super accurate reading. I just have to know whether or not it's there.

Before getting started, I just wanted to try one other thing. Uranyl nitrate was supposed to be fluorescent under UV, so I put some on a dish, turned off the lights, and shot it with my black light. It was definitely fluorescent.

This made me think that maybe to make the uranium glass, I could just directly throw the uranyl nitrate into some molten glass. However, when I looked it up, it didn't seem like that was the case. I could barely find anything about making uranium glass in general, but out of all the info that I did find, it always mentioned using something called sodium diuranate.

Based on this and considering the fact that I never made uranium glass before, I figured that it was probably best for me to use that as well. This meant that the project was going to be a bit more fun because I'd have to do some uranium chemistry, to convert the urinol nitrate into the sodium diuranate. To get this started, I had to add the uranyl nitrate to a beaker, and normally, I would have just quickly waited out on some paper and then dumped it in.

However, this time, I was working with uranium compound, so I had to be a lot more careful. This is because, the dust that it could let off, is not only radioactive, it's also toxic, and it can lead to heavy metal poisoning. To be as safe as possible, I carefully weighed everything directly in the beaker, and in total, I used about 15 grams.

Then on top of this, I dropped in a magnetic stir bar, and I poured in some water, which should have been enough to dissolve all of the uranyl nitrate. I turned on the stirring, and I waited for it all to disappear, but unfortunately, it ended up staying a little bit cloudy. I tried adding some more water just in case there wasn't enough, but it didn't seem to do very much.

This was unfortunate because it now meant that I had to clean things up a bit, and I didn't really want to have to work with a solution of uranium. Thankfully, however, cleaning it up wasn't exactly going to be super difficult, and I just had to do a quick filtration. I did this by passing it through some cotton and some sea light, which is like super fine sand.

The stuff that initially passes through tends to still be a bit cloudy, so I let it run for a bit, and then I swapped it out for a new beaker and put the other stuff through it again. After this, it was perfectly nice and clear, but there was still a bunch of uranium solution all over the funnel and in the cotton and sea light, so I washed it out with a bit of water. When all the water had eventually passed through, I took away the funnel, and the solution was pretty much good to go.

To convert this to the sodium diurinate, I had to react it with something called sodium hydroxide. This is also known as lye, and it's often sold as drain cleaner, and that's where I get all mine from. For this reaction, it also all had to be dissolved into water, but the exact concentration of it didn't really matter.

I figured that something around 30% by weight would probably be good, so I measured out about 70 milliliters of water and dumped in roughly 30 grams. It all dissolves relatively easily into water, but it also generates a lot of heat, so in the end, the solution is usually pretty hot. However, I wanted it to be closer to room temperature or maybe just slightly warm, so I put it in the fridge to cool it down.

When I felt that it was good, I took it out of the fridge, and I started slowly adding it to the uranyl nitrate. Almost immediately, it started forming these weird solid, doughnut-looking things, and this was all sodium diuranate. The reason this happened was because unlike the uranyl nitrate and the sodium hydroxide, the sodium diuranate is practically insoluble in water, so the moment that it formed, it separated out.

What I had to do now was basically just keep adding the sodium hydroxide until it stopped making the diuranate. At this point, it was still pretty simple because the solution was nice and clear, and it was really obvious to see. However, I eventually started stirring it and the whole thing got a bit murky, so I couldn't just rely on looking at it.

Instead, to know when it was done, I had to keep testing the pH. I did this just using some cheap pH papers, and I kept adding the hydroxide until it turned blue, which told me that the pH was about 10. After this, I just let it sit there for a bit to make sure that it all fully reacted, and then I filtered it off.

I just did this by pouring it through a simple coffee filter, and when most of the water had passed through, I washed it a few times with distilled water. I then let it sit there until all that water passed through as well. Now, I had some relatively clean sodium diuranate.

It was all still wet and goopy, and I'd have to dry it out, but it was going to take forever just sitting here in the strainer. With other chemicals, I'd usually just set up a fan on the side to help speed things up, but that would probably end up shooting a small amount of dust into the air, and I didn't really feel comfortable doing that with uranium. Instead, I carefully took out the coffee filter and I put it in a bowl, and I pulled a vacuum on it.

Under a vacuum, water vaporizes a lot more, and this makes it dry a lot faster. In a closed space, like in this vacuum chamber, there's nowhere for the water vapor to go. To fix this problem, I included a bunch of drying salt at the bottom, which would constantly pick up the water vapor.

I pulled it out about five hours later, and it was mostly dry. I purposely didn't let it dry completely because I wanted to avoid as much dust as I could. By keeping it slightly wet and a bit pasty, I was able to pretty safely scrape it all off, without making any death clouds.

Also, besides the safety issue, I was worried that if I let it dry completely, that it would just stick to the paper and become impossible to separate. I was able to get almost all of it and put it into a small bottle, but there was still some stuck to the paper. Getting this last bit was a lot sloppier than I wanted it to be, but I didn't really have any alternative.

I just did my best to scrape it all off, and then everything that even remotely came into contact with the uranium was put into a special waste container. Everything that I took off, was transferred to the same small bottle, and I did it as carefully as I could, but it was still a bit messy. There was a bit of uranium that managed to get on the outside of the bottle, and I, of course, had to clean that up.

I did this by just wiping it down a few times with some wet paper towel. With all the uranium safely in the bottle, and none of it on the outside to poison me when I touched it, I was ready to finish drying it. To do this, I put it into the same vacuum chamber that I used earlier, and I pulled a really strong vacuum on it.

I wanted it to be as absolutely dry as possible, so I left it in there for 3 or 4 days. I came back to it a few days later, repressurized the chamber and took it out. It worked.

It was really dry. When it's dry like this, it has a tendency to give off dust and powder, which is obviously really horrible to breathe in. This was why I only dried it completely in the final container that I was storing it in, so I wouldn't have to move it around or handle it.

I went ahead and weighed what I had here, and it came out to be 9 grams, which was about what I expected. Just for fun, I decided to test it with the Geiger counter, and you can see that the glass was able to block most of the radiation. The reading that it had was only barely above the normal background level, but that totally changed when I moved it over the top.

The reason this happened, was that most of the radiation that was being let off here was in the form of alpha and beta particles, and they just couldn't make it through the glass. As I mentioned before, this counter isn't able to pick up alpha particles in general. What I was seeing here was probably mostly from beta particles.

One other thing that I wanted to try was to shoot UV on it, and I was surprised that it didn't fluoresce. Maybe it was fluorescing, and it was just super weak, but as far as I could tell, it was pretty dead. I thought this was really interesting because logically, you'd assume that if you wanted to make glass fluoresce, you'd put something fluorescent in it.

However, I guess that just isn't the case, and glass chemistry is a bit more complicated than I thought. But anyway, now that I had the sodium diuranate, I could start trying to make the glass. However, I'd never made glass before, so I had no idea how to do it.

I looked around online, and one of the best things that I found was a video by Ben who runs the channel Applied Science. He gave a lot of good details and tips, and almost everything that I'll be doing here is based on stuff that I learned from him. I also got a few tips from Andy, who runs the channel called How to Make Everything.

When it comes to making glass, it's not super straightforward, and there are a lot of different ingredients that can be used. For beginners, Ben just recommended to use a mixture of three different things: silica, sodium carbonate, and boric acid. That's what I went with, and all these ingredients were really easy to get, and I just ordered them all from Amazon.

I then got a jar, added 60 grams of each, and shook it up to mix it a bit. Like this, it would probably work to make glass, but in my opinion, the powder was still too chunky. To fix this, I put it all into a blender, and I ran it for a few minutes.

This apparently worked pretty well, and after this, it was a super fine powder, and it looked like flour. This was definitely way better than before, and I hoped that it would give me a better quality glass. Before adding any uranium to it, it was a good idea to test it to make sure that it worked.

I had also never made glass before, and it was probably a good idea to get at least some experience making it before trying it with uranium in it. The general idea behind making glass was very simple, and all I had to do was melt this powder. I added a bunch of it to this dish that I had, which was normally used to melt things like gold, and I put it into a small furnace.

By the fact that it was glowing orange, it was obviously pretty hot, and I had set it to around 1,100°C. I wasn't completely sure that this would be hot enough to melt it, but when I checked on it a few minutes later, it looked like it was working. Because there was more space in the dish, I decided to add some more glass.

At this high temperature, the sodium carbonate was mostly just melting, but the boric acid was breaking down into boron trioxide and water vapor. This caused it to bubble a bit, and you can see this if you look really closely. The main purpose of these chemicals, was that they both have much lower melting points than silica, and they help lower the overall melting point of the mixture.

Pure silica only starts melting around 1,700°C, but at that point, it's still way too thick to work with, and you have to get it well over 2,000. Getting the temperature this high is just very hard in general, and because of this, additives are almost always included to lower the melting point. In my case, because I used boron trioxide, the final result would be some borosilicate glass.

In general, borosilicate glass is a lot less sensitive to big changes in temperature, and I hoped that this would help prevent the glass from cracking as it cooled down. But anyway, I let it sit like this for about 30 minutes, and I waited for it to completely liquefy. When it eventually looked like it was about ready, I used a blowtorch to preheat a graphite square.

Then I carefully got the dish from the furnace, and I poured out all the glass. I let it cool over the next 15 or 20 minutes, and it looked pretty decent. It looked like just a regular piece of glass, and I was actually pretty proud of it.

I really thought that it would crack, but apparently it didn't, and I was still a bit skeptical of it. I left it overnight to see if anything would change, and by the next day, it was still totally fine. As far as I could tell, this glass mixture worked pretty well, and the process seemed to be relatively simple.

After doing it just once, I was definitely by no means a pro at making glass, but I felt that I was ready to get the uranium involved. To do this, I just had to add some uranium to the glass mix, but it was still a bit too chunky. If I added it like this, it wouldn't mix in properly, and it would make some really uneven glass.

So far, I had really done my best to avoid working with any powdered uranium, but unfortunately, I didn't really have a choice here. I just did my best to grind it very carefully, and to try to make as little dust as possible. When I was done, I put it all back into the bottle, and everything that came into contact with the uranium, was put into my waste container.

To actually add it to the glass mix, the amount of uranium that I needed was super small. However, I didn't know exactly how much I had to add because from what I found online some recipes use as low as 0. 1% uranium and some as high as 3%.

This concentration was all done by weight, and I decided to go with a moderate 0. 25%. I figured that this way, if the final glass didn't glow well, I could just add some more.

At 0. 25%, barely any was needed, and for what I had here, I only had to add 0. 4 grams.

To mix it in, I shook it around for several minutes, and when I was done, it looked the same as it was before the uranium. As far as I could tell, it was still really white, and I guess there just wasn't enough of it to noticeably change the color. The dish from before was already in the furnace, and I started loading it up with some spoonfuls.

I waited for this all to melt, and then I added some more, and I left it there for about half an hour. Also, as a point of safety, this was all being done in my fume hood just in case it let off any uranium fumes. In reality, there probably wasn't much or any of it, but it was obviously something that I had to be very careful with.

When I checked on it, and it looked ready, I preheated that graphite block again. Then I took out the dish, and I poured out what was hopefully uranium glass. While it was still red-hot, it was hard to tell, but as it cooled, it was definitely colored this time.

It also shrank a bit, and when I felt that it was solid enough to move, I picked it up, and put it on some glass insulation. With a white background, the color was a lot easier to see, and it was a really nice and bright yellow. This was exactly what I was hoping it would look like, and so far, things seemed to be going pretty well.

The next thing to do was to test and see if it was fluorescent. I got out my UV lamp, turned it on, and it was working. The glass was definitely a bit green, but it wasn't very impressive to say the least.

My first assumption from this was that 0. 25% just wasn't enough uranium. However, then I thought, maybe it was just still too hot, and I had to wait for it to cool down.

I decided to have some patience and to test it again a few minutes later. This time, it still wasn't amazing, but it was for sure better than before. I then let it cool completely down to room temperature before testing again, and this time, it worked really well.

The 0. 25% of uranium that I used was apparently more than enough, and I guess I wasn't going to have to add any extra. There was still some glass left in the dish, so I poured it out as well, and I made another little flat glass thing.

This one also worked really well once it was at room temperature, and it glowed nicely under UV. After making these, it was getting late, so I had to leave everything and come back in the morning. Unfortunately, when I checked on the glass, one of them had spontaneously broke.

These pieces were a lot bigger than that first test run, and it was looking like this might cause some problems. One of them was still okay, and I thought that maybe only one of them breaking was just some bad luck. Then almost as it somehow knew what I was thinking, it responded by splitting in half right when it was sitting in front of me.

This was completely random, so I unfortunately didn't get it on camera, but this made it clear to me that there was an issue. This was happening because I had cooled down the glass quickly and unevenly, and it had caused a lot of internal stress. What I thought might work to fix this was to just insulate the glass and have it cooled down really slowly.

The final result would still be under high stress, but I was hoping that it would lower it enough just so that it would stop spontaneously falling apart. For this one, I also decided to try making it a lot bigger and I loaded up way more glass. I then poured it all out, and the moment that it looks solid enough, I put it between some insulation.

After that, I moved it to one of my benches to cool, and it initially seemed to be working well. However, a few hours later, I heard the sound of breaking glass, and this was what I came back to. A lot of stress had clearly built up, and it was apparently enough to shoot some of it a couple inches.

The pieces that survived didn't seem to be too fragile, at least when I was hitting them. However, shockingly them with heat probably would have caused them to pop. I decided to try breaking a piece of it with pliers, and it was surprisingly difficult.

The moment that it did break, it just exploded from all that internal stress. I thought this was really cool, but what I wasn't a fan of, was all the powdered uranium glass dust that was flying everywhere. After doing this, I realized my only real option was to anneal it.

To do this, I'd have to hold the glass at around 450°C for several hours. At this temperature, the glass is solid, but it's still liquid enough that its atoms are able to move around. This happens really slowly, which is why it takes several hours, but it lets them move to new positions and reduce the overall internal stress.

This is the proper way to do things, and it's what I ideally would have done before, but I was trying to avoid it because I only had one furnace. This makes it much more difficult and slow to do things, but I figured I would try it out. I still really wanted to make a big disk of it, so I melted the rest of the powder that I had, and I poured out another one.

Then as it was cooling, I quickly changed the furnace temperature to 450°C, and I put it in. To anneal this, it would take at least several hours and I was planning to leave it overnight. In the meantime, I collected all the broken glass that I had, and because now I didn't have a furnace, I melted it with a torch.

What I wanted to try here was to do some glassblowing with it, but I had no idea what I was doing, and it was a total failure. Instead, I just made several beads that I thought were small enough, that I could get away without annealing them. However, at the last minute, I got the genius idea to anneal them just in case.

I knew it was a bad idea to open the furnace, but I did it anyway, and it was, well, a bad idea. I tried to put it in quickly, but when the beaker touched the disk, it started forming a crack. I then tried to move it around to get a better look at it, and cracks formed everywhere that I touched.

I actually thought that this was pretty cool, but now I was worried that it would end up exploding again. I took it out, and I blasted it with a torch to heat it up again and to melt the surface. This way, I was hoping that even if there were cracks, if I sealed the top, it could prevent it from falling apart.

After this, I put it back into the furnace and I let everything anneal overnight. The next day, I was worried that I'd open it up and just see a disaster, but it turned out to be fine. I was initially a bit disappointed that the big piece got so cracked, but I actually ended up liking it.

I think having it like this made it a bit more interesting. I think the small beads that I made also turned out really well, and none of them were cracked or falling apart. The question that I had now, was how radioactive were these pieces of glass?

Considering the amount of uranium that I put into it, it was definitely quite low, but I still wanted to test it. The Geiger counter that I had wasn't the best for this, and I decided to invest in a better one. This one is much more sensitive and has a bigger detection area, and it can also detect alpha particles.

To test it out, I did it with the biggest piece, and with the uranium concentration of only 0. 25%, I assumed that the reading would be really low. However, it was more than what I got with the pure uranyl nitrate because it was now actually seeing the alpha particles.

The detector also had a totally different shape and a much larger surface area, which let it pick up many more particles. As a unit, cpm only shows the strict number of particles that it detects, and it doesn't differentiate between things like alpha, beta, or gamma. This is important in trying to judge how dangerous a radioactive source is because they aren't all equal.

For this reason, it's sometimes better to go with a different unit like Sieverts, which will take this into account. In micro Sieverts per hour, this gave a reading of about 5. 5.

According to this, which I got from the Canadian Nuclear Association, it means that if you held your cheek against it, it would be like getting a dental X-ray every two hours. For one of the beads, I got that it was only about 1. 3 micro Sieverts per hour, and this was just because it was a lot smaller.

In either case, at this level of radiation, this glass is generally safe to have around and to occasionally handle. However, it would be a very bad idea to fill your pockets with them or something, and to carry it around all the time. It might be okay to occasionally wear it as a necklace or something for a short period of time, but I don't think it's the greatest idea.

In a somewhat recent video, I said that I wasn't really going to be doing sponsorships anymore, and it was mostly because I didn't feel comfortable doing them. One of my biggest issues was that I didn't like being told what to say or to cover specific marketing or buzzword talking points. Even I would never promote something that I didn't genuinely like, I just didn't really like this part of it.

I decided, that I'd start doing them again if I could almost have completely free rein over them. When I came up with this idea, I honestly didn't think that anyone would actually do this. But to my surprise, Brilliant approached me and they did exactly that.

Before this, I had actually never heard of Brilliant, but I've been using it now for about a week and I really like it. I mostly use it on my phone, but it's also available on the computer by just going to their website, brilliant. org.

They offer a bunch of mini-courses in things like math, physics, chemistry, and computer science, and they do it in a way that I think is really fun. This is because they take a different and more active approach to learning that makes it feel a lot more like a game. They cover a lot of the fundamentals, and I've been mostly focusing on the physics ones, because physics has always been a huge hole in my knowledge.

What I also like is that it's really easy to start and stop, because it's broken up into a lot of small sections. I generally don't have a lot of time to do things, but I'm still progressing through it, even when I just randomly go on it for several minutes at a time. But with all that being said, if you're interested in learning something new, you should definitely check out Brilliant.

They offer a free version, which you can try out first, and then if you like it, you can sign up for the premium, which has a lot more material and many more features. Also, if you do decide to go with Premium, you should sign up using my link, which is brilliant. org/NileRed, because they're giving 20% off to the first 200 people that use it.

But anyway, I hope you guys enjoyed the video, and I'll see you on the next one. As usual, a big thanks goes out to all my supporters on Patreon. Everyone who supports me can see my videos at least 24 hours before I post them to YouTube.

Also, everyone on Patreon can directly message me. If you support me with $5 or more, you'll get your name at the end like you see here.

Related Videos

26:25

Making the world's most expensive carbonat...

NileRed

13,214,725 views

45:39

Making superconductors

NileRed

19,757,911 views

11:55

Making Uranium

Chemiolis

181,159 views

16:33

The "Impossible Torpedo" was real

Steve Mould

909,310 views

20:36

It's Happening - China Launches World's Fi...

Dr Ben Miles

1,845,678 views

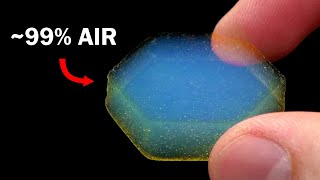

43:56

Making aerogel

NileRed

34,952,995 views

35:28

Making chocolate from scratch to feed an a...

NileBlue

8,446,916 views

27:11

You're Probably Wrong About Rainbows

Veritasium

3,730,243 views

19:53

Going supercritical.

NileBlue

5,646,401 views

23:05

This Should Be Impossible...

Alec Steele

1,186,297 views

1:08:11

Turning plastic gloves into hot sauce

NileRed

19,511,025 views

29:57

Making a bismuth knife to undo an injustice

NileBlue

14,467,023 views

45:56

Turning paint thinner into cherry soda

NileRed

8,979,796 views

21:35

Making American cheese to debunk a conspiracy

NileBlue

7,747,686 views

34:10

Making a deadly chemical in my parents' ga...

NileRed

6,985,269 views

13:19

This chemical really doesn't want to exist

NileRed

8,330,216 views

16:56

How To Make Ruby in a Microwave

NightHawkInLight

2,457,025 views

18:11

Turning a BLOB into PURE GOLD!

Modern Goldsmith

18,118,453 views

25:37

Making my favorite liquid carcinogen

NileRed

7,304,555 views

21:27

Hydrogen Peroxide: going all the way

Explosions&Fire

1,951,606 views