Mulheres das águas

1.21M views3230 WordsCopy TextShare

VideoSaúde Distribuidora da Fiocruz

Um retrato da vida e da luta das pescadoras nos manguezais do Nordeste do Brasil. O modo de vida e a...

Video Transcript:

I’ve been fishing since my childhood. This is quite interesting. My mom, whenever she would go to the sea, she would take me.

We end up passing on this culture of ours. My children go to the mangrove and there is a mangrove flower that we name ‘‘pipe’’. It’s a small flower that falls standing up.

So, when they leave, I tell them: "Don’t touch the pipe because the pipe will fall standing and the mangrove will be born already". This way, they already come with a sense of respect to the mangrove. For us, the mangrove is sacred.

There are days when I think that the tides are well arranged, so tidy, so pretty. There are days when it is upset, like… us women as well. There are days when we are more beautiful, and there are days when we are more upset.

Thus, I relate the mangrove and the mud to a woman. In fishing, we feel free. There’s this relation of feeling liberated and free.

At the mangrove, women sing on the mud, they sing at the mangrove. It’s a moment of bliss, that, at the same time one is working, one is happy sharing and talking to the mangrove itself. I love our mangroves.

Do you know why? Because it is from here that we take our nourishment. We don’t starve here in our community.

I’ve told you that whatever we need, we have here: fish, oisters, mussel, seacrab, aratu-crab. I am a fisher. Our mangrove has it all, without us having to ask favours from anyone.

When I say that the sea is a therapy, it’s because I was born there, I was born in it. It is its sound that makes me sleep, that makes me reflect. I like it because… I don’t know.

I myself don’t even know why, you know, but I like it. It’s not very profitable, but you can make a living out of it. It’s the thing I like to do.

When we see that big circle of the moon, really big, we know that the tide is good, and it will have a lot of seafood. There is no mud without mangrove. The mangrove has its role.

It is the mangrove that is the nursery of the crabs, among others and which is taken to the mud. Then, this relationship between the mangrove, the apicum-crab, the waters and mud is which cannot be dismissed. The mangrove is fundamental in our lives.

Women of the tides We leave home in our canoes in the morning, with the tide… it depends on the time, sometimes it is 7am, 7:30, 8am. We leave when the tide is full. And we row until… about 40 minutes or an hour away, depending on where we want to go.

We row a lot. When we get there, the tide is already lower. We wait a little bit, and then we start fishing.

We drink a little water, we eat a banana, eat a cracker, we put our shoes on, fix the fishing rod, put on the bait, we put a little bit of extra sunscreen, and we go fishing. The aratu-crab is very clever. There are people who catch it while fishing, they put a piece of dried meat, or sausage, tie it to a rope stay above the mangrove and make a noise to alert it wherever it is.

And then, it comes, because it’s very curious, looking for what made the noise. Then it comes and holds to the bait. Then one has a bucket, and then one pulls and throws it in the bucket, pulls and throws in the bucket.

Come on, aratu… come near, aratu… We go on shouting, whistling, singing, banging on the bucket… Come on, aratu. I do not see myself doing anyting else but fishing. All I know is to fish.

I provide for my two boys with the fishing. How can it be that this sea and this mud can not survive, or have no future? If I can live off of it, if I can pay my water and electricity off fishing?

I just fish. And how is it so that the artisinal fishing has no future? It is the sea that determines my work.

I have no boss. I love saying that: "I have no boss". Who decides is the tide.

It is the tide that tells me when to leave and when to come back. I think one of the biggest problems that we face in fishery today is this: there is no added value to our fish. We have no boss to keep us from going to the sea, but there is still the middleman that says: "This is the price for your fish.

I will not pay more than R$ 15 for a kilo of your fish’’ And you work really hard to catch that kilo. Women have always conducted activities in a bigger time frame than men. But, at the same time, we’ve always been stuck in a process of invisibility, because we were regarded as those who help.

That who helps and, at the same time, is in the catching procedure, in improvement and commercialization. We do it, we need to have the will power to do it. You cannot go soft on this job, oh, no.

You have to say that you’re going to do it and do it. And by taking a job here, give a slack here, catch up there… I go check the pan on the stove, come back, sit down and continue catching. Do you know what I mean?

The clothes are soaking, I am over here, but I get there quickly, then I rinse the clothes, put them up to dry, and come back. Our life is pretty rushed. We go on cracking, cracking, cracking.

Do you know how many aratu-crabs are there to add up… to that much weight? Say, for example, a kilo. It depends on their size, if they are bigger, or smaller, it’s about 160 to 200 aratu-crabs to make up a kilo.

Cracked, of course, just the meat. The bigger ones, then that would be maybe 100 or 120 aratu-crabs to make up a kilo of their meat. That’s the second part of our job at the mangrove.

To catch, no matter how good you are, you can get, in average, three kilos a day, those who are fast. The slower ones, they can catch one and a half to two kilos a day, but that is for working all day long. It is the woman who coordinates.

It is the woman who administers. In the world of fishing, for instance, and I believe it is so all around Brazil, the fisherwomen coordinate their homes. Hence, in the context of the quilombola issue, when it comes to fishing, it is them who take control over the situation, even when conflict arises, if necessary.

The women are in the frontline of these conflicts. The women are also the most vulnerable to these conflicts. They are vulnerable to the arrival of these enterprises.

Actually, women are vulnerable to anything, but also empowered by the discourse they possess, and in the way they run their families life styles. So, we are not just fighting for our life quality, but also for those who eat our fish the fish distributed by the free fairs to the whole region and everywhere else. So, the fight is about securing the territory, is about the health of these women.

And let the government find a way to improve the quality of their work. Come, fellow men, no more indecision. Come, enlarge the rank, spread the flag of liberation.

Come, fellow women, this is our moment. Come from all sides and, arm in arm, join the movement. Let’s all together raise our way of life In the fishing ground, to live and work.

From North to South, how pretty, to see the classe organized. Joining men and women. Following the march on foot.

Look, here is the sugar cane, there is Goiana. When they set fire to this area, this polution goes all inside of the village. This here is a "baldo".

It’s called a "baldo", this mud barrier, which was made by the machines. It is dug so that the river won’t come this way anymore. This here could all be a mangrove field, our estuary.

That cannot be anymore, because this dike is made for the sugar cane plantation where the poison is placed, and when it rains, it falls down into the river. Look here how the water is flowing black, from here to the sea. Here is where the residues flow When the residue pours, it is through there, through this pipe.

Look at the difference in the water that flows from the refinery without residues, so to speak. Look how it comes from there and falls into the river. The pesticide that the airplane dropps onto the sugar cane field, it kills.

When the airplane doesn't come, then come the men with masks on their faces and with those pumps on their backs and they spray it on the sugar canes, manually. When it rains, it flows into the river and then it all over It stinks! It smells bad and the fish are all dead, belly up, floating.

Sometimes we come here to the river margins… It is called "Roundup", this poison. It is called "Roundup"… We come here often, and when we arrive we take pity on it. Big fish, small fish, it all turns white, with their bellies up.

Smell the stench. Most fishers that leave here to take the preventive test at the local health clinic, they get a germ called ‘‘coccobacillus’’. Most fishers, they all have it.

When we get to the health clinic, we get a cream to put in the vagina, but everyday is the same fight is the same, we have to be in the water. We feel an itch, a burning. It is an itch that stings, but we use the cream and it goes away for 15 days, one month without feeling that but the struggle is the same and after a month, we get the same symptom all over again.

That's it… The polution here is discharged with the tide and on the mangroves because there is no sewerage system for the discharge. The sewers are short… it is small, it is at the shore It should extend, maybe if it was extended further, there would be less polution. I just want my island to have basic sanitation.

So that we can feel like we’re people, and not see our sewage going to the sea, our feces on the water, floating in a place that was supposed to be sacred for our children to bathe for us to catch our shellfish with dignity. And not to hear reports that it is polluted. To us, Petrobras is synonymous with misery, it is synonymous with hunger.

We live surrounded by… I, for instance, live in a community that has 14 oil wells. Almost every year, the Landulpho Alves Refinery has a spill. In 2009 and 2008, there were the biggest spills in Brazil and it was here in my community.

Even today we suffer the consequences. The lack of fish relates to the big spills from the companies, that is, the Landulpho Alves Refinery, Proquigel, Dow Chemical, the Aratu Port, that is coming up with an expansion model. Expanding the port means an impact.

Now, they talk of Thermoelectric Complex, which is the largest thermal power plant in Latin America. To generate energy, they will use that product from Petrobras, the "bunker", which is a crude oil, without treatment. This material causes a so called "acid rain", which for our lives is another contamination.

When we go investigate and check out what this causes… at the least, it is cancer. A little further from here, geographically, close to the Margarida Salt Mine, is the "Enseada do Paraguaçu Shipyard". This enterprise brought up several environmental impacts, the rocks here were imploded, many hectares of mangroves were destroyed and we went through 2013, the worst year for fishing.

And now comes Fiat, comes the glass factory, comes the drug factory, and other industries that will soon be here. Whatever benifts that may bring, so far we have seen nothing. When these folks here from Goiana finish building these industries, they will be unemployed.

We must preserve our tide, our river, our mangrove, because that is the only industry where we will never see a closed door to our fishers. Where will all these people go if we lose the sea and the mangroves? If we lose our fish, then what are we going to live by?

I can't do anything else and not even want to! So, how are we going to live by? To survive on what?

There hasn’t been a single year that we haven’t felt an impact of these companies around our mangroves. And then it gets complicated, it kills the mangrove, it kills the nursery, and our lives, it is our bodies, as you have seen, my body is in the mud. And the mud is already with a chemical product that will cause some sort of disease to us, fisherwomen, with our bodies dumped in this mud.

Enough! There are times when they are deep down and we can’t catch them. We wander a lot to catch a kilo, two kilos of aratu-crab.

We walk a lot, indeed, going up and down the mangroves, walking in deep mud. We get all beaten. We take out the oyster, fill this bucket.

This here, filled with oyster, weights around 20 kilos or more. Oysters are heavy. From here we drag it all the way outside, to the canal… inside the mud pulling weight.

We are artisan fishers. We work very hard. The fatigue is stressful.

We end up in a situation, sometimes, it's enough… There is no way one is not feeling any pain. It is difficult, in such a job, to come home and say: ’I don’t feel any pain at all, I am fine’’. It’s difficult.

Because it does hurt. I stay like this. Then, when I get tired and my back hurts a little, sometimes my knees, I switch positions and I stay like this.

Do you get it? With the basket almost full, I put the bucket on my head, I kneel with the bucket on my head, I take the basket and throw it up. Sometimes, this arm of mine hurts like hell.

There are days when I can’t even raise it. One needs to create an instrument from the need to listen to these people. It is useless to do things without listening and sitting with us to get it organized.

So, the occupational disease, it was… The discussion about the occupational disease, by Professor Paulo Pena. Paulo Pena came to the community, went to the mangroves, to see how we did it and how we worked, and which difficulties we were facing. And along with us that became a wonderful thing… fisherwomen have a policy to deal with occupational diseases.

When we are ill and we realize that there is no way to do this job of ours, we must refer to a doctor so that we can improve our health issues and continue our work. But sometimes we go the doctor and we’re cared for. There are doctors who don’t even look at our faces.

Sometimes they barely ask us what we feel. They give us worm medication, dypirone and that’s it. We can’t even speak.

If they gave us a proper report so that we could go to the social welfare and get the benefits that would be a good thing for us. But whoever goes gets it denied. We, fisherwomen, when we reach 55 years of age, we can retire.

When I filed my retirement request, the first time, it was denied. I filed it a second time, and it was denied again. In my case, I tried three times.

It is hopeless! That way, I’m turning 59, which I did and still not retired. These are just some of the issues that many of us have and that the State simply does not recognize.

That the Government just denies as if it had… … people trained to deny these right to our people. It seems like the State goes to college to get specialized in denying rights to these people. In 2011, when this school started, there was a lot of people here.

Everybody quiet, not really understanding much. We would go around in fear, hesitating to speak up. But we started studying at school and to understand what the school was telling us: No, you don’t have to be silent, you must say what you are feeling, you must show what your community is feeling, what your community is going through.

With that, today, I am not afraid nor ashamed to say anywhere, that I am a fisher. Because earlier, most times, we were ashamed to say that we are fishers, because that was bad. We would go to the welfare office and you should not have your nails painted because that would be bad.

Then, you were not a fisher… if your nails were painted and your hair was tidy. Today, we learn from what is in the Law, and we must understand what the Law grants us. School assures us that, it has taught us that.

As well as teaching us to think about formation and educational processes and not processes of getting sicker It is about bringing first our history and our way of life. Let’s go try to catch some crabby. Fishing today is not easy.

We know the guaiamum-crab is there because of their poop, this poop at the border of the hole. We know it is there. So we take this stick.

Support it… when it goes in, it moves so it automatically closes. We must cover it from the sun so that it doesn’t get killed by heat, cover it up and just leave it. The next day, we come, and it’s closed down, like this.

We open it and it is inside. This is our life. It’s not easy, no, no, it’s tough.

But there we are, fighting. And we want our mangroves clean, free from pesticides, free from sewage. We do not want our mangrove to be dirty with pollution because this is where we provide to our folks.

And with all these difficulties that we have, even so, there are women and men that are out here all the time, especially women, fighting, resisting, because it could be a lot worse hadn’t we had the initiative to organize ourselves and be struggling, both as fishers and as people. In each corner, where we know that we are signing a death sentence to our people, we occupy it. And we will have to occupy other offices, we blockade the highway, we shut the ports, like the Port of Aratu, we assemble in the refineries, we will do everything that we believe we must do so that our lives are… so that we can survive this model that is out there that, for the sake of development, is threatening our lives.

Related Videos

38:30

Globo Reporter - Nordeste diferente Full H...

MV Technology

2,677,350 views

28:00

Como é morar em um flutuante na Amazônia? ...

Narrativas Femininas Pelo Mundo | Paula Cristina

1,078,182 views

30:52

As Sementes

VideoSaúde Distribuidora da Fiocruz

25,996 views

14:11

Na cadeia produtiva do sururu, mulheres tr...

Repórter Record Investigação

375,735 views

29:30

paraiso desconhecido

Altair Pimenta

1,072,711 views

32:22

Plongée au coeur du delta du Congo | 360° ...

ARTE Family FR

254,946 views

22:02

Eu Sou Quebradeira - Histórias e Tradição

Eu Sou Quebradeira / Histórias e Tradição

59,965 views

42:09

SOZINHO NO PIOR PAÍS DA ASIA, BANGLADESH 🇧🇩

Nômade Raiz

1,335,313 views

41:11

Single mother and baby - went to the strea...

Single mom life

1,640,560 views

56:27

Dona Raimundinha Do Rio Tajapuru 56'30

Chico Carneiro

660,605 views

43:15

A vida na cidade mais gelada do nordeste b...

Boa Sorte Viajante - Matheus Boa Sorte

696,641 views

30:52

AS SEMENTES legendas em português

Sead (Agricultura Familiar)

19,858 views

49:49

PESCA PERIGOSA no LAGO das ARIRANHAS, ELAS...

Gil Trindade. Vida Selvagem na Amazônia

1,318,138 views

29:18

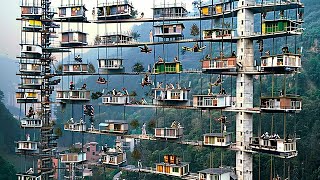

Pode Ser Difícil de Acreditar, Mas Pessoas...

#Refúgio Mental

4,009,485 views

20:14

Documentário l Marisqueiras da Ilha de Deus

Produção Visual

31,366 views

51:42

Mennonites - The most closed community in ...

Notre Monde

1,303,840 views

53:08

The Organic Gold Hunters of the Himalayas ...

Free Documentary

1,057,080 views

1:18:27

A Lei da Água - Filme Completo

O2 Play Filmes

2,618,678 views

16:33

MARISQUEIRAS - VIDA DE RAÇA

Nany Medeiros

11,384 views

30:53

Assim é a Vida na ÍNDIA: O PAÍS MAIS SUJO ...

FEITO GEO

1,610,718 views