Customizing your Character: Brandon Sanderson's Writing Lecture #6 (2025)

153.63k views12555 WordsCopy TextShare

Brandon Sanderson

Last week we talked about how to make your characters worth rooting for (or against), but this week ...

Video Transcript:

BRANDON: Hey! Welcome to Brandon Sanderson's Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy lectures from 2025. Today we're doing our second week on character. I do this as a hybrid one where I do some lecturing and a little bit extra Q&A because we lost a week to some technical difficulties. But I get to everything that I wanted to get to today. So come and join us for Week 2 of Character. Hey! We're going to do a second--I almost said episode. Hey, welcome to the Brandon Show! CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: We're going to do a second lecture on character today.

I will try to be a little more liberal with letting questions be asked, because, you know, we aren't going to have a Q&A lecture for this one specifically. So you'll have to save those questions and sneak them in. But I did want to get the second lecture on character to you because last time I only got kind of to the really core idea of motivation. And that's not really the presentation of the character. Right? Like, I feel the stuff we talked about last time is the most important thing to making a character kind of function

in a narrative sense. But what we didn't talk about is how you actually present them. And to the audience, the stuff we're going to talk about today is actually what they would say is the more important stuff. This is the sort of stuff they bond to that makes the character memorable. So it's kind of interesting. Like, behind the scenes, I'm really focused on, all right, what makes this character have rooting interest? What makes this character dynamic so they're changing? What makes this character proactive? Or how am I building the story such that a character who

is not proactive doesn't impede the story, so that readers don't turn against the character for impeding the story. These are all those things. But today we're going to talk about personality and things like that. I did want to throw up a mention of iconic characters. This is not my phrasing. I got this from Howard Taylor, who got it from someone else. And I wanted to take a moment to mention iconic characters are the phrasing I prefer to use for characters who do not have character arcs, who do not necessarily change story to story. And there

are a lot of these. Sometimes they'll have a mini character arc in a given story. But that arc is not relevant to their entire personality. These are characters whose stories are written to be read out of order. Right? Oh, hi, baby! CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Getting started early on writing your stories. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Iconic characters are people like--James Bone is kind of the classic example. Right? James Bone, Dirk Pitt, who I mentioned before. But it also kind of goes to the Babysitter's Club" to the Hardy Boys, to some things like this. Those are the obvious

examples. But you can probably think of stories where a character's personality and arc is not as important as their external arc. I would say that in Elantris, my first published book, Raoden has mostly an external arc. And the idea with that character being that you sometimes just don't have a character changing. Now, Raoden has what we call an apprentice arc. Right? He's going up in understanding and knowledge, and so he does have some movement on the sliders. But his conflict is mostly external. This is kind of key for iconic characters. The question--now we like competence.

We like proactivity. We can really handle in some genres characters where the competence and the proactivity are such that we don't care if the character's learning anything. Sometimes we maybe get a little tired of every character having to learn something. And sometimes you just want to watch someone pick up bazookas and blow things up and do a very good job of it. And in these cases, the question is not "Will the character learn to use the Force in time?" The question becomes "Is this the time where the villains are just so capable that our iconic

hero is unable to save the day in time?" and/or "What does it cost this character to save the day in time?" And you can probably think of some stories that you have very much enjoyed where the resolution is bittersweet because the character was extremely capable, but capable enough to save most people but not everybody, and these sorts of things. And so in general I recommend character arcs. Not a hot take. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: However, there is definitely a place for a character thought of as an iconic character who's fighting against something more external. They can

be very fun to read. And they can be very poignant. Right? Like, I would argue that a lot of Agatha Christie novels are like this. And some of the really most powerful Agatha Christie novels have characters, like Hercule Poirot, who are not necessarily changing, but the emotional journey they go through on that one book, even though, you know, you could read them out of order, can be super poignant and emotional and have a lot of depth, even though the story's not about, you know, Hercule Poirot overcoming his individual flaws. Sometimes he does have his limitations

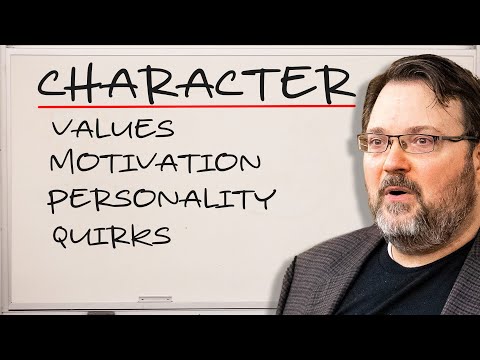

and things like that that he has to deal with. I wanted to get that out there kind of as a coda to last week's lecture before we talk about kind of the three things that I think are how you present a character to the reader. So we did all this work behind the scenes. Now to what you do. Well, you want to be able to present these three things: personality, motivation, and values. Right? And I would say these three things are interconnected. Motivation is what does the character want? Right? Personality is how does the character

express what they want out of life? And values are what are they willing to do or to give up in order to get what they want? And I build them around, in my mind, these kind of core ideas. And so we're going to take these one at a time. We'll go ahead with the one in the middle. I should have reversed those. Let's talk motivation. We talked about it last week, but I wanted to give you a chance to ask questions on this and to kind of dig into it. Motivation, I would say, it's the

first and most important one for your character. Your discovery writers are going to find it often while you're writing. The character motivation will grow out of what you're trying to do with that story and with that character. I am often asking a bunch of questions--and I have that as the last bullet point--in order to find my character motivation. And I am usually searching for it a little bit while I'm writing. I believe I told you guys this, but I generally outline heavily my plot and my world, but I do not outline my characters as extensively.

I then go to the story and start writing them as I am searching for these three things: personality, motivation, values. And I'm exploring different manifestations of how I could express these things. And as I'm finding them, I'm jumping back to the outline and rebuilding the outline now that I know who the characters are. And I find that if I don't do it this way that I either just come up with all this stuff and throw it away, or I am very rigid with it and then the character doesn't seem to have a life to them.

And so kind of--I mentioned this before. I had three Vins before I arrived at the Vin that worked. Right? I had two Kaladins before I arrived at the Kaladin that worked. Dalinar was always Dalinar. He worked on the first try. He just is who he is. Like, the Dalinar that you read about is the same Dalinar in 2002, who is the same Dalinar who's in the story I started writing when I was 16. So Dalinar's just Dalinar, too stubborn to be anybody else. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: But this is--I'm hunting these things, and I'm asking myself

some questions along the motivation. And there's--I just jotted down a bunch of these questions that I'm asking myself kind of naturally as I'm writing. One is backstory. What in this character's history informs why they make the decisions that they do right now. This can be tragic or not. Not every character needs a tragic backstory. But I feel like it's a pretty valid thing to say that a lot of the decisions that we make and the motivations that we have come from what we learned when we were younger and the people that we have become as

we've made decisions. What key decisions? Right? You know, influenced this character? I suggest asking yourself kind of the hard questions on this character. Right? Like, what doesn't this person want people to know about them? And how much does that inform the choices that they make? Not every character needs something like this, or needs that exact question, but most characters need something like this. What failure will they never repeat? And how do they interact with blaming themselves for failures? Some people interact with those things in different ways. You know, flaws, hinderances, limitations, all of these things

kind of play into that. The classic Hollywood way of doing this is to ask yourself "What does the character want? Why can't they have it? What does the character need? And what must they sacrifice to have that?" And those kind of variations on those four questions come up quite often when you're looking at kind of Hollywood works and things like that. With all of these questions, I'm asking myself the why. One of the more--the ways that people--I've asked a lot of authors how they come up with characters. And most of them responded some measure of

instinct and gut. Like, we study plot more than we tend to study character as writers. But a lot of them, you'll press them and they'll be like, some of them use a dossier. This is a list of questions they ask themselves about every character. You can find sample ones online. Everybody has, you know, their own take on it. I just gave you some of the ones I ask myself. Some people, like, keep a list of those to help them distinguish characters. I have a friend who looks through a magazine searching for a picture of a

non-famous person, just the ads and stuff, of somebody they're like, "This is my character." And once they see the person, then she knows, "Oh, this is how they would act. This is who they are." And things like this. Everyone has their own methods. But one of the key things to make a character work is to figure out some fundamentals of who they are and what decisions they would make so that you are able to extrapolate that. Let me see if I can explain this better. And I'm going to use kind of an odd metaphor. You're

used to that from me. I get very detailed, mind-bending questions about the worldbuilding of the Cosmere, of my books. Specifically, "How would this intricate, minute thing about the magic interact with this very obscure aspect of magic on another world?" I get a lot of questions like that. I am often able to answer those, not because I have considered that corner case, but because I have fundamental rules that the magic for the Cosmere works upon, so that I know that if I answer that question here, I can answer it in a way that in the future,

if I were to ask myself that same question, not remembering I'd answered it, I will answer it in the same way because I'm extrapolating from the same core fundamental ideals that make the magic system work. I look for that in my characters. The idea being that I can anticipate how this character would act because of these few core things about them, so that if they ever deviate from this I know I need to make sure that there's an explanation in text because the reader will get a sense for this. So motivation is just--it's going to

inform the rest of this. What do they want? Why do they want it? What about their backstory, personality, or the things we talked about last week, inform why they want these things? Questions about this before we go on to personality, which is kind of like the veneer that you put on this character after you've figured out their motivations. Again, this is the--sorry, I shouldn't tap for--here you go. Listen to that. ASMR. Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: You're going to have so much fun. Yeah. Tayin's nodding. It went pop. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: They will

probably cut that for you. You can thank Donald, wherever he went. He's not--oh, Donald's not here. He was back at the office. STUDENT: He had to do something else. BRANDON: He had to do something else. Well, Donald eventually will cut that out for you. Let's go to some questions. Ask me some questions. STUDENT: How do you establish villain motivations when often it's just take over the world? BRANDON: Right. How do you establish villain motivations when it's often just take over the world? Let me quote Pat Rothfuss, one of my favorite Pat Rothfuss quotes. I'm sitting

on a panel with Pat, and someone says, you know, like, "What do you do with this?" And he's like, "Well, make sure not to do the one where they all want to destroy the world, because who really wants to destroy the world? That's where all their stuff is." CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: So how do you establish villain motivations, and how do you make it so that it's realistic? And this can be a challenge. Right? Because it's been done so many times. I would say that if you can come up with key motivations that caused this then

you are going to get a lot of mileage. When I said the why. Magneto wants to potentially destroy all humans, and if not, enslave them. Why? If you know Magneto you can answer that. Right? Well, Magneto was put in a concentration camp. He realized it was "me or them. Humans will do the same things to mutants in the future. Therefore, I have to strike first and make sure I can never be put in that situation again." It's a completely, like, you know, kill all humans. Basically, that's what he ends up trying to do in the

first X-Men film. You know, he thinks it might not kill them, but then he realizes it will and just kind of goes forward with it. Right? And that's just a horrible, horrible thing. But you understand. Now, you can have iconic villains kind of in the same way that you don't understand. I often talk about Lord of the Rings in this example. Lord of the Rings would probably not be strengthened as a film trilogy or as a book series if you had in-depth knowledge of what Sauron's motivations are. Right? Sauron in those stories is an iconic

villain whose job is to represent a giant, terrible force that has to be reckoned with. That's totally fine. To offset that, Tolkien makes sure to include Gollum, who has a very understandable motivation. He's been corrupted by the Ring, which is kind of a representation of power and things like that. But it's what's corrupting Frodo. It becomes very relatable in that specific instance. So you can see what his motives are. He just wants the Ring. Why? Because this force of evil has warped him and he's really kind of pathetic because of it. You don't have to--.

When we talk magic systems we'll talk about external and internal logic. You don't have to have external logic for why, you know, the motives of the Ring, or why the power of the Ring corrupts. That's not, you know--. Internal logic is usually enough. Meaning, internally it's consistent. So how do you do this? Well, those are two kind of extremes, where you can make someone iconic, or you can give them something very relatable. If the motive makes sense but is taken to extreme, a lot of times villains are made with a tragic flaw, without which they

would be a hero. Right? And that flaw is often that they're willing to go to extremes. Magneto, "Hey, mutants are in trouble. I learned from the Holocaust that humans will destroy the other with even less reason in that case, with no reason, and they'll do it here because they're afraid of us. Therefore, I need to make sure the mutants are protected." He takes it the step further. "So I'm going to destroy them all first." Right? So there's some clues on that. If all else fails, make Sauron sexy. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: And hope it works. CLASS:

(laughing) BRANDON: Sorry, I had to throw that in. I'm talking about this iconic hero, and then there's stupid sexy Sauron going skiing with Homer. All right. All right. What else have we got? Over here. STUDENT: Do you have any advice for writing, like, nonhuman characters that the main character does interact with? BRANDON: Yeah. Nonhuman characters that the main character does interact with. One of the keys to remember here, and I don't think I talked about it last week, is how you treat a viewpoint character and a non-viewpoint character is very different in narrative. And this

goes for your villain question as well. If you're willing to give them viewpoints, which you don't always want to do, you will instantly humanize through use of viewpoint. When we see through someone's eyes, we get an instant burst of empathy usually for them. And from there it depends on how relatable you make their motivations, even if they are--. Like, often your motivation can be relatable, and your execution can be alien, and it'll still work very well. For instance, you know, we all love our family. If the alien has a very alien type of family, it's

like, "All of them are my clones," well, that's an alien type, but we all understand loving your family. And so if you want to humanize them and make them more sympathetic, you make their motivations very relatable, even if the manifestation is alien and show it through their eyes. If you're not going to show through their eyes, then usually how we perceive the character will depend on how the viewpoint characters perceive them, unless you are doing the reversal. Right? If you are laying it on thick, you can flip it on its head. Oftentimes, this is what

you do with a character who is--. Like, if you have a character who themselves is unrelatable, and they see an alien and think, "Ah, those stupid aliens. I hate them. We will immediately bomb," to the alien instead of the character because you've already expressed this character's values are opposite from our own. Right? And so are you going to use the viewpoint? Vernor Vinge in A Fire Upon the Deep is a fantastic place to go for--oh, you got it right there. STUDENT: I was looking it up because, like, those are books that really show how to

do that well. BRANDON: Yeah. So what Vernor Vinge does very well--he's one of the masters of science fiction. If you like Dune, you'll probably like A Fire Upon the Deep. Just, it's a very different book, but it has that same sort of depth of worldbuilding and kind of epic scope. And in this he has an alien species, which is just brilliant. And the alien species is they are a group mind, not a hive mind, of doglike creatures. Like, four to five individuals come together, and they become a complete individual. And on their own they're only

fragments. They're not smart enough to be a full individual. You would think this is completely unrelatable. But the moment you're through their eyes, the motivations are very relatable, and you just immediately click with this group of dog creatures that have been shattered, and they have one piece of a great hero who's part of their, you know--. Like, and it's so interesting, but it also is super relatable. So that's one thing. The less you show us and the less the main characters know, the more sense of wonder, which can be scary wonder, or it can be

inviting wonder, depending on your tone, you will have. The more viewpoints you show, the more you'll instantly humanize. And so it really kind of depends on what you want to do. You're writing fantasy, so you do want--or science fiction--your alien characters, I would say, to express something that could not really work in the human experience, in order to be like otherwise why are you having this alien. So historically, a lot of them are just to take a human attribute and to magnify them by 10. Right? These are the Klingons. They are a warrior race. These

are the Vulcans. They're very, you know, they're very logical, things like that. But, you know, I would ask yourself that question. You're going to go to this alien, and like, what makes them--why couldn't you do this with a human character. And then how much do you want to make them sympathetic? How much do you want to give them viewpoints and things like that? Does that help at all? Great. Other questions. Yeah. Right here, and then we'll hop back there. STUDENT: How do you make background characters distinct from each other? BRANDON: Yeah. How do you make

background characters distinct? So this is going to be one of those things you're going to have to practice a lot and learn. I recommend one of a couple of things. Right? For all of your characters, even your viewpoint characters--you don't need them as much for your viewpoint characters--I do recommend some sort of visual signifier that the reader can latch onto to remember them until they are comfortable with their personality, whereupon this thing does not have to necessarily be, you know, a feature. But if this is the only person in the group with glasses, and you

highlight that every time, it will help them click. Right? And if, in the same way, they have a distinctive motivation--this is what we kind of talk about with quirks--that just comes out, is the type that can come out naturally in conversation. You don't need both, but sometimes both are good. But what you're looking at is the reader's going to be searching, "Who is this again?" Oh, yeah. This is the person who just absolutely loves, or has a weird interaction with water. Water is strange. Robert Jordan did this. Right? It's the whole Fremen thing. He took

that to an extreme for a culture in his. It's like, how this character interacts to a cup of water just sitting there. How can you just leave a cup of water? Like, that coming out repeatedly, so it reinforces. Now, the thing you're going to deal with, with this in a book, is this is instantly going to stereotype that character. OK? Because we don't know them yet, that's going to form the stereotype. You're going to either, in some books you leave that character kind of as a stereotype of themselves. You try not to stereotype entire groups

this way. But you can leave them and just be like, this is this quirky character. They don't have--you know, this is who they are. They're there for comic relief. Right? Relief. You know, when most people get stuck to the wall with Stormlight, they're like, "Get me off." Lopen starts proposing to the floor. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: This is who they are and things like that. And having that. But you're going to want to move beyond that. A couple ways to move beyond that is eventually give them a viewpoint, or to give them a heart to heart

with the main character where you start to get some of this stuff that you can't, you know, "Why are you like this?" "Well, maybe like this." Understanding that sometimes it's just your personality, and not everything has to have deeper meaning. But, you know, why are you like this? Or how does who you are make you interact with the world? Right? And then also if you're having them be a representative of a fantasy race or something, I would recommend making sure there's an array of characters from that culture who you let us see what are some

cultural things and what are some individual things, so not every Vulcan becomes Spock. And, you know, that's not a criticism of Spock. Spock needed to do what Spock needed to do. Spock needed you to be able to go to this TV show that you maybe have never seen an episode before. Right? Spock needed to be iconic. Kirk needed to be iconic. Bones needed to be iconic. You needed to be able to come into it, watch them out of order, know who they are. And for that reason, all Vulcans kind of needed to be Spock, because

otherwise, you know, there's too much there. It's not an epic fantasy story. It's a half-hour TV program. Or an hour long? How long was the original Star Trek? STAFF: An hour? BRANDON: It was an hour. Yeah. An hour with a lot of ads, but an hour. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: By the way, have you guys ever gone back and watched original Star Trek and you're like, "The soft filters. The soft filters." Any time there's a woman on screen it's like, "Ooooh!" It really is. It looks like they're having their senior photos in high school taken. Right?

And then it cuts back to Kirk and he's just like flat, you know, regular. And then you go back and there's a totally different lens zoomed in. And, you know, like, ah. The Khan episode is great, but the stock filter in the Khan episode. Anyway. So the time that they had is very different from the time you had. So do try to take that extra time and things like this. But remember, they'll be remembered for their quirks first. And so you can lean into that and use that, and then you add depth over time. OK?

Yeah? STUDENT: How many characters should we flesh out in our story? BRANDON: How many characters should you flesh out in your story? It depends on a couple of things. It's an excellent question. How much space do you have, and what subgenre are you in, and what type of story are you telling? All right? So, rule of thumb, the more viewpoints you add, the longer your book will get, and it kind of is exponential. So one viewpoint, very easy to write even a short story from one viewpoint. Right? Two main viewpoints, it becomes really--you can do

it, but it becomes much harder. It starts to have this magnifying effect and things like that. I recommend just keep in mind a few things. The really good book with one or two viewpoints, in a reader's mind, compared to the really good book with 10 viewpoints they like equally much. But this one for a writer's skill is 10 times harder. So as you're a newer writer, if this is what you love to write, write that. Don't worry. Right? But as a newer writer, if you're choosing between projects, being able to control bouncing between two viewpoints,

or doing one first person viewpoint that is really well handled, the end result's quality, the reader's not going to be like--. Well, some people do prefer the big epics, granted. But those can be equally good books. But this one's chances of spiraling out of control on you are enormous. So if it's your first book, I might recommend one or two viewpoint characters. Two, most people can handle. It teaches you to swap and how to balance chapters. With two viewpoints what you can do is when one is boring you can cut to the other. And you're

used to this format because of network television, which usually uses A plot/B plot. And the reason they do that is, like, a character's like, "And now I need to get from here to here." Cut. Other characters arrive to the place that they were going. And you do all this and then cut. And you're at this character. So you can cut the boring stuff. You can still do that in one viewpoint. You just put a pound sign, put a blank line and they cut. But there's some momentum that happens when you're jumping back and forth. Learning

the two-viewpoint narrative can be really handy for that reason. However, a couple other rules of thumb. The more people whose--the more plotlines you have, the more it goes out of control as well. So for instance, two characters who are part of, like, a romance, that are both in the same place, interacting with each other, does not expand the scope of the novel as much as two people on two different continents, working with different parts of the worldbuilding, with different goals. OK? And so you can do that. But if you add like, you're like, "I want

to do four characters," but it's two sets of two, that's way easier than four in different places coming together. But that can be really satisfying. Right? So in The Stormlight Archive I did four. Right? We have the Kaladin plotline. We have the Shallan plotline. We have the Dalinar plotline. And we have the Szeth plotline. And they are slowly kind of intersecting. And we have some sub-viewpoints to some of those. For instance, we're doing Adolin viewpoints with Dalinar viewpoints. Adding Adolin on actually helped keep the book--it made the book work way better. He wasn't in the

original drafts. So having a second viewpoint there that I can take off some of this stuff and add to him ended up helping, and that didn't expand the scope of the novel. I made that swap. I took some of the scenes that had been Dalinar, and I maybe added, you know, 5% of the book to add an entirely new viewpoint character. But it was completely subsumed by another character's plot arc. If that makes sense. So just be aware. Like, Way of Kings is 400,000 words. OK? That's what it took me to do pretty well four

viewpoints. And one of those, Szeth, is barely getting any. OK? So there you go. Viewpoint clusters. Ask yourself how many arcs, how many viewpoints you're going to have, and these sorts of things. And then I guess the other thing I was going to say is your genre. Right? If you're on a fast-paced thriller with a lot of external conflict, you have much less time for introspection. Because you have less time for introspection, you're going to be able to do a much weaker job with character arcs and motivations than you normally would. If you are writing--I'm

reading an Emily Henry book right now. My wife likes them. Do you guys like Emily Henry? It's a romance novel. And every chapter is just flirting. Right? CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: There's a plot, but the real plot of this story--it's actually very good--but the real plot of this story is "Woman is around doing something. She accidentally bumps into guy that she's totally not going to hook up with. They flirt forever and then break. And then she goes somewhere else, and he happens to be there too. And he's like, 'Are you stalking me?' 'No, I'm not stalking

you.' Flirt, flirt, flirt, flirt, flirt. Break, chapter, next scene. He's there too!" Right? CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Like, "Flirt, flirt, flirt, flirt, flirt." Right? Like, that's how those books go. You have a ton of room for introspection in those things, particularly if it's like a first person viewpoint, which I think this might be, from the woman's viewpoint, not trying to do anybody else's. She can spend so much time on, you know, how she interacts with her sister. How she interacted with her mother. Because, you know, the story is not the world is going to explode, and

we have seven hours to stop it and we're having to--. The story is, you know as soon as we get done with this scene she's going to show up somewhere else and he's going to be there, and they're going to grouchily flirt. And that's the whole book. So there you are. I'll put a mild content warning on that one. We are at BYU. I haven't gotten to any parts that wouldn't be more than mild. But I'm not to the end yet. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: So it might be more than a mild content warning. So yeah.

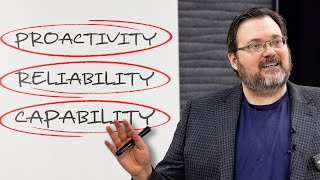

So there you are. Go ahead. STUDENT: So annoying characters are annoying to read. How could I keep readers engaged and, heaven forbid, even like that person? BRANDON: How do you make people like annoying characters? And how do you keep them reading? Well, you've got the tools, the keep them reading part. Right? It's proactivity, pacing, promise, progress. Like if you're making progress--. The most annoying thing to a reader is not a character being annoying. It's a character standing in the way of the plot moving forward. Right? They will deal with a character that they individually find

annoying if the story is moving. Now, how can you minimize that character being annoying? Well, you can have your viewpoint character find them annoying too, and find ways to not, like--. If the joke is, "Oh, no. I have to deal with this person." Right? Or it does something interesting to the character. Otherwise, it's like, why do you have this character if their only purpose is to annoy the reader? Maybe that's not a character to have. Right? Most of the characters that work that are annoying, like, it's because of the impact on a viewpoint character, or

it's the viewpoint character realizing they're going too far and trying to curtail these things and, you know, working with themselves. Like they're a little bit more annoying at the beginning. Right? Like, Donkey annoys Shrek. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: But we laugh because Shrek being annoyed is funny. Right? CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: So we are less annoyed by Donkey than Shrek is because we get to laugh at Shrek. Right? And, you know, Shrek gets to voice the frustrations we have and then in other places Donkey is there to offer some emotional heart, which moves the story along, which

we like. I guess I would ask yourself, what's the purpose of your annoying character? There's definitely some reasons for them. All right. Way in the back. Then we'll get to some of you over here. STUDENT: In the same vein-- BRANDON: Mm hmm. STUDENT: How do you write a character that you just want your readers to hate? BRANDON: How do you write a character that you just want the readers to hate? So there's different levels of hate. There's the ones you love to hate. And love to hate usually works when this character is like--what do we

love to hate? We love to hate a character who is competent and all of these things but is at the same time just doing stuff that is, like, loathsome. We love to hate them because the loathsome stuff they're doing is also not--how shall we say? It's not so bad that you feel bad reading it. Does that make sense? And so a character we love to hate is somebody like that. Right? Who's the best we love to hate? STUDENT: Thanos. STUDENT: Doofenshmirtz. BRANDON: Doofenshmirtz? We just love Doofenshmirtz. Right? CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: We just love him. Thanos

is a better example. Right? Like, what Thanos is doing is awful. Right? But, like, he moves the story along so much, and we don't have to watch a lot of it, and the heroes get to face him down. And it's like, you know they're going to save the world eventually. How else do you write a character that you hate? Well, make sure that they interfere with the hero's--they hit the heroes in their weaknesses. If they hit the heroes in their limitations, it's even more. Right? Like, if you hit Superman, if you take Kryptonite and you

get Superman, "Oh, we hate you." If you exploit the fact that Superman has a moral code, we hate you even more. Right? And so just kind of look--make sure that they're hitting the heroes in the place that they're vulnerable in ways that'll make us, you know, really hate them. It's more than simple cruelty. It's cruelty that impedes the people that we like, is probably your best bet. All right. We're going to go over here. We'll go back there, and then we'll hop over here. STUDENT: Yeah. How do you handle characters shifting motivations as they discover

information? BRANDON: Yeah. How do you have characters shifting motivations as they discover new information? That's an excellent question because in most books that's what you want to have happen. Your character arc is really about a shift in motivations. In fact, the best character arcs generally are. When someone, like, really loves a character arc, it's because Kuzco has moved from wanting his new summer palace to wanting friends and protecting those friends. Right? And so how do you do this? Well, this is your job showing the progress. Right? You establish the motivation early, and you either show

that it's short-sighted. "I need to get the power converters." "You need to save the entire galaxy, Luke." "But the power converters." Like, he doesn't really want to get the power converters. He's annoyed by it. But that kind of represents "I have to get back to Aunt--I can't actually go on the adventure." Show you're going to show steps early on. Your promise is this person's scope needs to be expanded. Bilbo, we want you to go on an adventure with dwarves and steal from a dragon. We don't want you to sit at home and be peaceful. I'm

sorry. So we want your motivations to shift over time and we want to show that you're acquiring new motivations. And slow progress on that. Right? And give us something we want that the character doesn't yet want. Show why it would be good for them, and show over time them acquiring a new value, which replaces their motivations. OK? Now, you can backslide too. You can go the other direction. And in that case they're acquiring, you know, a new value that is detrimental to who they are, and that's replacing their motivations. We haven't really gotten to values

yet, but you can figure that one out. Right? Makes sense? All right. Go ahead. STUDENT: So question. Kind of what you were talking about, about introspection before. If you're writing from the viewpoint of a character who's, like, intentionally very introspective and is getting distracted a lot and is commenting on everything, how do you still feel like the plot's moving forward-- BRANDON: Yeah. STUDENT: If he's always kind of commenting? BRANDON: OK. So you've got a character who likes to comment on everything. They're very introspective. We call this navel gazing, in writing parlance. The character's naval gazing.

They're looking inward. But how do you keep the plot moving if this is this type of character? Lots of ways you can do this. Bilbo's a classic example of this. Right? He's kind of forced out into the world. He would be just sitting and thinking about which cheese, you know, which cheese tastes the best on which given day. And then he finds that he really likes adventure, to the point that, you know, he writes a whole book about it and later on he wishes he were back on adventure. So he's acquired a new value. One

of the things you're going to have to do is you're going to have to use external forces to keep them moving and pulling them back. Or you make their voice so darn readable and interesting that we don't notice that they're navel gazing. This is the thing you will find in a lot of first person romance novels, and/or those snarky YA teen girl protagonists. Right? That because the writing is so interesting that you don't mind so much. Like Jane Austen, one of the great writers of all time. Jane Austen, it's because of--and it's not even first

person--but it's because of the voice of the prose and the character that we are engaged by scenes that normally don't feel like they're moving the plot along very much. But we're there for the voice. And one of the things that I should tell you about, like, plot, progress, payoff. Right? Like, that's how you make a kind of classic plot work. Remember not everybody is there for plot. That's if you want a plot to be engaging. Sometimes people are there for voice. Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. You are reading Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy for voice.

So promise, progress, payoff is not, like--this is seventh on the list of important things for that book series. And if it flubs it at some point, usually it's done intentionally, because he was a brilliant writer, to service one of the things earlier on the list. The humor is more important than whether the mechanics of the worldbuilding make sense, and the kind of message is more important, and the voice is more important in those books. One of the reasons I like Pratchett so much is because he's able to balance these two things and have a plot

be important and some of these voice and things, you know. Like, I think that balance, for me, works better than it does in Hitchhiker's. But Hitchhiker's is brilliant. And the fact that you would, like, go this whole lecture on plot, progress, payoff. You'd hand it to Douglas Adams. He'd be like, "Ph-h-h." You know. Throw it over his shoulder and go write one of the best science fiction books of all time. Means that people read for different things and different books do different things. So keep that in mind. OK? Some books are about the introspection. You

can lean into that. You can make it work. But your voice is going to be really, really handy for that, and kind of like--. If you can make it so that introspection is relevant to what the reader wants to be reading for that given book and the subgenre, you're going to be able to get away with more of it. In general, editors try to trim this back, and they're usually right. You usually need less of this than you think. But as writers we love it. Right? We are there for characters sitting and navel gazing for

chapters on end because that's why we write is the contemplate the world and dance through flowers and things like that. But, you know. All right? OK. Right here. STUDENT: So--it's me? BRANDON: Yes, it is you. STUDENT: Sorry. BRANDON: Yeah. You can't ever tell. Sometimes I point--yeah. STUDENT: So how can you illustrate, especially, like, introspectively with an internal monologue, like, the gradual higher improvement or debasing of a character's morals? BRANDON: Yeah. How do you show the improvement or debasing of a person's morals? This does go back to promise, progress, payoff. Right? This is where, like, oftentimes

you will, for a character arc, show somebody being unable or unwilling, depending on the type of character arc, to do something early on. And you present them other opportunities through the story to achieve those same things. Right? That is why Better Off Dead--deep cut--starts with a character trying to ski a hill, and then the big, climactic ending moment he has to ski that same hill. Right? And he's failed every other time. Better Off Dead is a parody of a teen sports drama done as a comedy. But it still uses the same structure. In the same

way, you might show somebody making a good choice early in the book, that in the middle you know what their choice would have been, but they're presented with the same thing and this time they slide a little, and the next time they slide a little. Just make sure the reason for that value swap is there, that changing motivation. We understand why. Right? Though it's not handled brilliantly, everybody's seen it, so Episodes 1, 2 and 3 are there to show the debasement of an idealistic Jedi. And the point is showing the change in values based on

him falling in love and the person that he loves life being worth more to him than the values of the institution that raised him. Right? And you see that over time. Again, it can be kind of clunky, but the arc is there. What George was trying to do was there. And it's a good illustration of this. And so you know at the end when he makes the decision to go against Mace Windu that it's not a decision he would have made earlier. And you've seen him not make that decision but start to think about it

a little bit. So there you are. Any in this one? And then we're going to go to some more. Yeah. Right here in the stripes. On your--yeah. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: You've got stripes. Mm hmm. STUDENT: Are we going to have a lecture like more on romance? Because my-- BRANDON: Hey! What an excellent segue. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: What an excellent segue. So next week you will have some guest lecturers because I'm in Hawaii. Yay! It's a writing retreat with all of my officers. So we're all going to Hawaii. It's what we're spending the Wheel of Time

money on. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: I consult on the Wheel of Time television show, and they pay me, like, $100,000 or something, and we're just going to use that and go to Hawaii. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Me, and Dan, and Adam, and my wife, and everybody will be sitting in hammocks and thinking about all of you back here where it's actually going to be kind of warm next week. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: We should have gone, you know, last week when it was all snowy so I could--. But anyway, our guest lecturers are going to be Jenn and

Becky. And they are--. So I had a fun experience with them. Like, my 15 person class often has people who do not look like traditional students. Shall we say that? Meaning they're old people like me. Right? Like, you go in the class and you're like, "Oh, you're in your 40s and 50s." And it's because, you know, my class is an evening class and anybody can take it, and it's just based off of, you know, how good your writing sample is. Well, it turns out that two of the people there who were more my age were

professional novelists. They had a bit of a leg up in the submissions thing. And they're both romance novelists who wanted to learn to write fantasy. And so they are both indie published. They both earn--I won't give away how much money they earn, but they earn significant livings with their writing. Like, what you would consider a good living that I think most of the people in this room would be like, "I would take that job." Right? They're doing very well with their writing. They know indie publishing and they both write romance. Romantasy being the thing right

now, I asked them to adjust their lecture. I often have them in. And usually they're in while I'm here, so I've heard their lecture multiple times. I asked them to add a section on romance. Because it is the big thing right now, I figured having two romance experts talk about romance and about indue publishing--. Because as I warned you, I know indie publishing from the perspective of somebody for whom indie publishing is skewed and distorted. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: So yeah. So next week, I'll just pass the romance buck along to Jenn and Becky. I've already

asked them to prepare that lecture, and theoretically you should have a good time. I know their other lecture. I think it's really solid. It just talks about indie publishing really well. you seem very eager to-- STUDENT: I was just curious what their last names were? BRANDON: It's Becky Monson and Jennifer Neilsen? Neal? Peel, Peel, Jennifer Peel. Yeah. Becky Monson and Jennifer Peel. Yeah. You can look them up and maybe check out their books. They both published the books they were writing in my class. They were fantasy novels, but they're really romance novels with a fantastical

elements. So I can't take too much credit. But they did seem to really enjoy the class. They were a huge advantage to the 15 person class, just workshopping with extra professional writers. So there you are. So that'll be the lecture. We are going to try to record that. Hopefully, we won't have any hiccups. But we'll see what happens with that, and, you know, and things. All right. So Jennifer Peel and Becky Monson next week. All right. So we talked a little bit--well, we talked a lot about motivation. Let's talk about personality. So personality is how

you express the things that you want for your characters. I'm not talking about your personality. Things like this. A lot of the stuff I was saying about the side characters comes into play here. But you can if you want use one of the--I don't know if I want to call them pseudoscience--we'll say science adjacent personality profile quizzes that people love, that are usually letters and/or colors, pretending all people fit into one of those. Totally not the same thing as horoscopes. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: But people swear by them, and I don't want to get in trouble.

I know some of you really love them. And you're like, "I'm an IED," or whatever it is. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: There might be a J in there. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Really the thing to keep in mind is you can simplify this. Right? So with your character, how do they go about getting what they want? That's going to be a big part of their personality. Meaning, are they aggressive about it? Are they passive about it? Are they one who will just jump out and speak up what they want? Will they stay back and work it into

a conversation? Will they never mention it? You know, how do they manifest? If they love their family, how do they manifest that? Some people manifest that by, you know, how they take care of people. Other people manifest that by writing a check. And how does your character manifest this value or motivation that they have, and how can the reader latch onto that? Once again, at the beginning every character's going to come off as a stereotype mixed with an archetype. Right? They're going to be, "All right, this is the wallflower who never speaks up for what

they want and lets everybody walk all over them." You will add nuance as the story goes. And if you want to, you know, start off, like, with a main character, you can just out of the gate say, "Yeah, this is the wallflower who doesn't speak up for what they want, unless you do X, and then they scream in your face." You can start with a contradiction for a main character. I recommend against it generally for the side characters, but you can make that their thing. But start getting us into this idea. Like, your early promises

are who is this character? How do they go about? What is the text going to treat as a flaw that they need to overcome? And what is it going to treat not as a flaw? Right? What is it going to treat as something that is just like, we love the fact that the character is like this. We don't want them to abandon that aspect of themselves. The text doesn't want them to. They have to work around it, but they're not necessarily going to abandon it. And trying to get across the personality of the character, dialogue

and the first actions they take are going to be your keys to this. Dialogue can do so much heavy lifting in stories. You have to watch out for maid and butler. Have I talked about this before? Yeah. What you don't want to do is have them come up and say their motivations. But your dialogue can show how they express themselves and their motivations. And one of the things that I do recommend that writers try is having three characters in a scene and trying to write a scene where they all, you know, want things and stuff

like that with no dialogue tags and no setting descriptions. Yeah. And see how can you make your characters distinctive with three characters, so it's not just a back and forth. Some are interjecting. It's all messy. It's not 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3. How can you make it so that the reader never loses track? If you can learn this, it will strengthen your dialogue. And it's one of the places to find personality for your characters. You can use dialogue cues or viewpoint cues now and then. They can be overused, but they can be useful. Gambit

gets a lot of mileage out of having a Cajun accent and the way that he speaks. It can be, like, dialects can be grating. Usually less is more in books because you have to write it out. Usually you want to give flourishes and things like that. But remember this should still evoke something deeper about the character. I recommend against some of the ones that have become cliche. For instance, to show someone intelligent, traditionally diction, a lot of times they'll be like they don't use contractions, and they use words that, you know, the $20 words that

nobody knows. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: You've probably seen these before. It does work. Be careful though. I've known some people who are very intelligent. You guys might know that my college roommate was a guy named Ken Jennings. Right? Is that a surprise to some of you? Yeah, some of you. Ken Jennings. I was there when he was winning on Jeopardy and he would not tell us how many he'd won because he was under NDA, and we just watched and watched, and he kept winning and he kept winning, and finally he was able to tell us, "Yeah,

I won the whole season. I have to go back and keep filming." CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: "That's how long I kept winning." Right? Ken does--Ken uses contractions. Ken doesn't use $20 words. Once in a while he'll throw one out when it's really precise. He's precise. He uses the right word, not just a word to sound smart but because it is a better word, and he speaks, when he's with other very intelligent people, he starts shifting into a new language we call Simpson's Quotesism. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: He speaks almost entirely in Simpson's quotes. I'm exaggerating. But the

references, and the kind of cutting each other off because they know what each other are going to say, and then the zingers of jokes, and the sort of twisting phrases, they do that a ton. That's how those very intelligent people interface with dialogue. And it's nothing--doesn't sound like Spock at all. Doesn't sound like your traditional "Well, we have a this much percent chance of this, and long word that nobody knows." I've met a lot of intelligent people. They don't talk like that. But they do use rhetorical devices in conversation. Meaning, they have been educated so

they know how to make a thesis statement when they start talking, they support with evidence, and then they wrap up with a conclusion, even if it is "This is the best Simpson's episode, and I'll tell you why." Right? Like, "You know the quotes. It's this quote." Like, highly educated people will organize their thoughts differently. Their sentences will become more complex, and they will build off of each other. This is something I've noticed. If you can get that down in your diction, you will have a different kind of depth of evoking "this is an intelligent character"

than simply having them not use contractions. You will do some of the other stuff. Like, there are times where I, like, you know, I have a character who just loves big words. That's like an aspect. That's a little different. They'll use these and then people will make fun of them. They're like, "It's just a really nice word. Listen to it." Like, that's a character attribute, and that kind of gets into the quirks. Finding a few quirks that you can use for your character, and if those can manifest in their motivations a little bit, they can

relate to them, they can come out in their diction and their viewpoint, those are the quirks that will really pull a reader in. And it depends on your subgenre, and your mileage may vary. David from The Reckoners, which is one of the book series I've written, being really bad at metaphors. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: It worked wonderfully. Right? It really did work wonderfully, and readers responded to it very well. I tried something similar in The Frugal Wizard's Handbook for Surviving Medieval England, where the guy's just like rating everything out of star values, and it didn't work

as well. Right? In his viewpoint. And so, you know, one felt very natural to David. Why it felt very natural to David is his personality is he jumps into things before he thinks them through. That's kind of a core attribute of him. He will jump into metaphors without thinking of what the metaphor means, and he'd just have to come up with something. And his brain works in a different way, and he just says it. And it only makes sense to him. It actually reinforces his primary character trait. The other just felt tacked on. It felt

like quirk for quirk's sake. I felt like it worked better than, you know, than its biggest detractors. But it is a weaker one for that reason. And hopefully that can explain to you, like, having your quirks reinforce somehow your theme and your character in certain ways is going to be helpful for you. Let's do some more questions. So who else wants to ask questions about characters? Yeah. Back there. STUDENT: I'm a big fan of the Cohen brothers and how they, like, write characters. BRANDON: Yeah. OK. STUDENT: Their side characters are very good at just kind

of like giving you a very good understanding of them in a short amount of time. BRANDON: Yeah. STUDENT: How do you kind of like translate that to, like, prose? BRANDON: So the question is, he really likes the Cohen brothers, and Cohen brothers are very good at side characters and making everyone very distinctive. How can you translate that to prose? So what makes a Cohen Brother film work is that it's, like, a parody--. Imagine a parody is, like, 100% exaggeration. And a Cohen Brothers film is a 10% exaggeration instead. Because you're doing just that slight exaggeration,

and you're making it a loving exaggeration instead of a point at and laugh, that exaggeration kind of exemplifies things like this. And so because of that, they'll take a certain interesting piece of diction, and they will exaggerate it by 10%. And they will take, like, character motivations, and they are larger than life. They are exaggerated a little bit. In order--even for the life that someone's living, even if it's a normal life. Right? They exaggerate it by 10%. And they allow the humor of situational comedy to creep into the drama, and then they hit you with

the drama with kind of a left hook. It's a very specific, individual, and kind of brilliant mixing of these things. If I were going to try to do this in prose, I would pick something that looks linguistically interesting on the page, and I would exaggerate it by, like, 10%. And how you're going to work that's going to depend very individually on you. There are certain things you can get across very well, and certain things that would be a little bit harder. But I think you could figure it out. So exaggerate the dialects, just by like

10%. And then make sure you have that mixture. Like, they try really hard that as the situations get ridiculous, the motivations of the human, the protagonist, are so relatable that you're able to push through. And so I would have that little extra ridiculousness of a story. Like, don't go as far as Pratchett. But it's kind of like that sort of thing. He's doing the same thing. He's turning that dial up to 75% instead of to 10%. That's what I would recommend. I've never sat down and actually tried it. Probably the closest I get is from

some of the Hoid story narratives where he does kind of the same thing. Like when you're reading Tress, some things are dialed up, like, 10% about character personalities and the way that people act, where you can kind of tell Hoid's exaggerating a little bit. That's what I'd recommend. Yeah, over here, and then we'll come up here. You've been raising a lot. Sorry. Yeah, I did see you. We'll get there and then come down here. STUDENT: Have you read The Sun Eater? BRANDON: I have not read The Sun Eater. STUDENT: OK. I'll have to phrase this

a different way then. BRANDON: Uh huh. STUDENT: Thoughts on, like, characters that, if we're not in their own viewpoint would totally be a villain? BRANDON: Yeah. Thoughts on characters that if we're not in their viewpoint they would be the villain. This is a whole host of types of story, a whole genre. What are your thoughts? Well, that's what books are really good at. Books are really good at showing you through the eyes of somebody and expressing their own motivations in their own eyes. I don't think that we need to spend a lot of time on

tips for that because it's a natural strength of the genre. It's actually much harder in film than it is in books because you have that natural viewpoint. Like, as we're seeing through someone's eyes, we understand their rationale. Just make sure that their motivations are really sympathetic, and you're probably going to be OK. And, you know, you can also have in a book, if you want, you know, someone, he would be, or she, they would be a villain in another story. You can show that they didn't intend these consequences, and had actually planned to try to

make sure they didn't happen. But some freak accident made it occur. Right? And so there were casualties. But you can also show that they think that if they don't do what they're trying to do, the world will end, or things like that. Like, you have so much power to explain and rationalize the viewpoint character that I would argue that a whole host of stories that we all love, the characters would be seen as villains externally because--but we have extra information from the viewpoint. So yeah. All right. Go ahead. STUDENT: For, like, a pretty beginner writer

specifically. BRANDON: Mm hmm. STUDENT: If you want to tell a story that focuses around a group of people, but you have a main viewpoint, like maybe like five people, what do you think is the easiest way to help them all stand out but not, like, get [unclear] too much. BRANDON: Yeah. Yeah. Make a medium-large cast of characters all stand out? Contrast is your friend here. Being able to have two characters in a situation where they will talk about how they'd make opposite choices will segregate them in our mind into the person who would do this

and the person who would do that. And by putting them together in situations and showing how each of them act--. Now again, this will start stereotyping them. In fact, you can think of how any ensemble cast of any show or book starts off as, all right, this is the tough one, this is the sneaky one, this is the one who's open hearted. Right? Whether it's Lost, or whether it's, you know, The Lord of the Rings, you know, The Fellowship. And then they get more time to kind of break out of that mold over time. But

it's that contrast. Right? Like, let's look at Lord of the Rings. Boromir's the one who wants the Ring. Gimli wants to hit it with his ax. Right? CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: There's a contrast. Gandalph refuses it and is terrified of it. Nobody else is, but Gandalph is terrified. How they all respond to this one simple thing--. You don't want Merry and Pippin to get it because they would lose it. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Right? Like it's just--you know how they would all treat the ring, and you build from that. That contrast is absolutely your most important thing

in giving us our initial kind of feel for an ensemble cast. STUDENT: Thank you. BRANDON: Yeah. Go ahead. STUDENT: If you're signposting, like, a betrayal. BRANDON: Yes. STUDENT: What's a good way to do that? BRANDON: Signpost a betrayal? It depends on what kind of betrayal it is. in Dune, the betrayal is signposted by having the traitor say, "Well, I'm going to betray them." That creates suspense rather than mystery. Right? What emotion are you looking for from this? And, like, what kind of signposting are you looking to do? Is this a betrayal of a dear friend?

Well, you start off by showing the friendship and why--. But then you have to subtly indicate the shifting of values so that when the actual betrayal happens--. Or if it's someone who's been sneaky all along and is just there to betray someone, you want in that case to be able to look through and find all the clues. And one of your best things you can do is have a Sixth Sense moment where when your reveal happens the main character thinks of all the things that they should have seen that were the clues. Not to spoil

The Sixth Sense, but there's a moment at the end where it's like, "Here's all the stuff you missed." And you're like, "Oh, I saw all of that and it was right there." Those sorts of moments are really handy. But it depends on if you want mystery or suspense, if you want shock, what emotion you're looking for. STUDENT: Thanks. BRANDON: Mm hmm. What have we got? All right. We'll go here and then to the baby. CLASS: (laughing) BRANDON: Baby's got a question. STUDENT: How do you make sure dialogue doesn't drag on? BRANDON: How do you make

sure dialogue doesn't drag on? Breaking it up does wonders. Readers’ eyes start to glaze over if one person is talking too much. But the same information cut up with people interjecting and chatting helps a ton. Make sure that all the characters are participating. We want to avoid a Socratic dialogue. As good as they are for what they're doing, a Socratic dialogue is "guy talks about how awesome he is, and another person asks really leading question to let them answer it in a really interesting way." That starts to read like a soapbox essay where the characters

are not participating. Characters disagreeing, characters kind of having a little fight through their dialogue and treating it a bit like an action scene, will all help speed it up. And then good old fashioned screen writing adage, "In late. Out early." In late. Out early is just a, you want to start any given scene as late as possible to the interesting things happening, and you want to get out as early as possible after the interesting things happen. What are the interesting things? That's, you know--. But just the adage of, can I get this closer to the

parts that are really going to be succulent and great is a good adage to have. So usually readers prefer dialogue to narration, usually. So as long as it's snappy and working. You obviously want a balance of both in most books. But usually they prefer it. All right. STUDENT: How can I write a character that's influenced by a background that I've never had? BRANDON: How do you write a character? How do you write--? So there are entire sequences, in fact, I think Writing Excuses has done multiple episodes about, you know, writing the other, is what they

call this. So there's a couple of things. And this is a big question, so we'll end here. I'll be on this for four minutes. So number one, reading primary sources is just enormously helpful. We live in a wonderful age where everybody--everything you'd want to read about somebody has written about. In fact, one of the best things that they'll do is they'll often write about "Here is what media gets wrong about X. I am a forensic scientist. Here is what people get wrong about forensic science." That'll tell you so much. What do people get wrong about

living as a transgender person in the United States. Read that. It will tell you. What does media get wrong, and things like that. It will tell you so much. So read primary sources. Number two, remember that people are, you know, characters are human beings, and any given human being doesn't fit their mold perfectly. So you can write a character who doesn't fit their mold in some ways, as long as you're getting other things right. There will be some things that are just individual to that character. There aren't a lot of women like Spensa. Right? You

know? But there are some. And so just remembering that and making sure that you're getting some things that are common to the experience and some things that are individual to the character and making sure you're highlighting the individual ones as kind of different for that character. Having primary sources read your story and tell you what you're doing wrong. Like, Skyward got so much better because I went and got fighter pilots to read it. And I said, "All right. What am I doing wrong?" They're like, "Oh, this, this, and this." And, you know, some of them

were extensive rewrites but the book got so much better because I had actual fighter pilots tell me what it feels like. And it turns out them reading my prose, trying to stumble through, using primary sources has been super helpful. Dissociative identity disorder is another one. Like, I needed a ton of help with that. And a lot of times you can't tell the ones you're doing a good job with and ones you're doing a bad job with until you get some of those reads. Because some things that I thought I was confident in, turns out people

read it and were like, "Yeah, that matches mine." And having a variety of reads. Right? Like, if you can get three or four people because, again, people are individuals. Living with dissociative identity disorder is different for each individual. And so I had three different people, I believe it was, read for us and, you know, as long as things were conceivable that a character with this could do this, and I was hitting the hallmarks in other places, then it worked. And ask yourself, you know, in some of these cases you want to be careful not to

be doing damage. Right? And a lot of the times, like, that's the biggest worry. If you're wanting to write someone's life experience, and you are one of the, you know--. Like in my case I'm a very popular author. I'm one of the few people who a lot of people will read in a year. If I get something wrong and perpetuate a stereotype, it can just be devastating to the readers who are like, you know, like, "Everyone thinks this about us." We got a reader on Tress of the Emerald Sea, and they were like, "Everyone gets

this wrong. We can't lip read nearly as well as TV and books make us. And it actually causes harm for us because people just assume we can follow a conversation when lip reading is just not capable of doing what media has made it." I'm like, "Oh, I don't want to make that worse." Because it makes their lives just a little bit harder when everyone assumes that they can lip read. So in that case, having that authentic source--. And so what we do is if it's somebody we go out for that, we actually pay them. And

there are some people who this is part of their job, and they tend to be very good at it. As a new writer you may not be able to do that. But you still can ask on forums and things, and have people look at the specific scenes and give you some feedback. The authenticity will make your story better. In every case where one of these has come up and I've changed it and stretched further, my story has been better for all readers, not just for those. And if you want to know why, go watch the

99% Invisible podcast on curb cuts to kind of understand how learning about something like this can improve everybody. But anyway, there's my thing. Thank you for that question. I'm glad you asked it. I'll be gone next week, and we'll do Sanderson's Laws of Magic the week I get back. CLASS: (cheering and applause)

Related Videos

1:13:32

Sanderson's Laws of Magic - Brandon Sander...

Brandon Sanderson

141,110 views

1:10:10

Creating Proactive, Relatable, and Capable...

Brandon Sanderson

176,548 views

2:54:47

Stormlight Archive - FULL STORY RECAP BEFO...

Wizards and Warriors

447,477 views

1:15:53

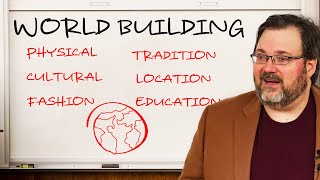

The Tools to Make Your Worlds Better - Bra...

Brandon Sanderson

125,230 views

Summer Cabin Jazz | Soft Jazz Melodies Wit...

Whispering Jazz Melody

31:44

Types of Character Arcs - Brandon Sanderso...

Brandon Sanderson

67,801 views

1:16:36

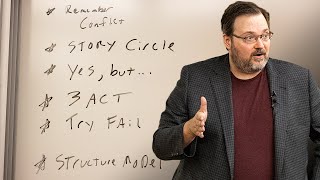

Story Structures - Plot Theory: Brandon Sa...

Brandon Sanderson

262,089 views

15:40

How To Spot Bad Writing - Jack Grapes

Film Courage

144,258 views

37:03

Frequently Asked Questions on Writing Plot...

Brandon Sanderson

169,288 views

22:49

Why Great Writers Steal Ideas | With Brand...

Hello Future Me

169,333 views

1:15:55

Plot Q&A: Brandon Sanderson's Writing Lect...

Brandon Sanderson

183,313 views

24:43

Answering Your Worldbuilding Questions - B...

Brandon Sanderson

47,257 views

🌿 Tranquil Beach Café Jazz Music | Mornin...

Dream Jazz Melody

23:24

Brandon Sanderson talks Tolkien, Fantasy, ...

Nerd of the Rings

108,964 views

3:10:32

Brandon Sanderson — Building a Fiction Emp...

Tim Ferriss

180,561 views

1:13:56

How To Worldbuild on Earth? - Brandon Sand...

Brandon Sanderson

87,614 views

1:15:11

How Publishing Works - Brandon Sanderson's...

Brandon Sanderson

67,233 views

38:55

Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing ...

The Royal Institution

2,610,945 views

22:36

What Makes a Good D&D Character?

Pointy Hat

1,178,740 views

1:12:14

Lecture #9: Characters — Brandon Sanderson...

Brandon Sanderson

905,614 views