Le Salse Madri in un 2 stelle Michelin francese con Giuliano Sperandio - Le Taillevent**

1.53M views1666 WordsCopy TextShare

Italia Squisita

🇮🇹 Giuliano Sperandio è lo chef in copertina del numero 45 della rivista ItaliaSquisita, con la su...

Video Transcript:

Good morning, everyone! I'm Giuliano Sperandio, kitchen chef in the restaurant Le Taillevent in Paris. Today with Italia Squisita we decided to delve into and analyze a topic that is as interesting as vast: mother sauces according to Auguste Escoffier, who was the first person to codify French cuisine.

The mother sauces are four plus one. The four mother sauces are the espagnole, the velouté, the béchamel, the tomato sauce, and an intruder, which is the fifth, which according to Escoffier gets to be part of the cold mother sauces, which is mayonnaise. It's considered as an intruder as, first of all, it's cold, and because, differently from the hot mother sauces, it's emulsified, as well.

For this reason, we dedicated a separate video to the making of a mayonnaise, with the more classic method of hand making. The analysis on mother sauces was also made to understand that mother sauces are indeed the mothers to many other sauces, but these mothers also have grandmothers because an espagnole has at its mother a brown souce, a velouté has at its mother, in turn, a veal white stock, a chicken white stock or a fish fumet. Base sauce will be the protagonists of this video.

Let's start from the one I use as base, that for me is chicken stock. In order to make a chicken stock, we're adding chicken wings as a base. We can clearly use some chicken carcasses, thighs or a whole chicken.

I'm covering these chicken wings with cold water and bringing to a boil. Initially, you can notice how the water is dirty, let's say, with the impurities from the chicken. As the water temperature gradually raises, we can see how this water becomes whitish, until the impurities start coagulating.

These impurities, once it boiled and they coagulated, are removed with a skimmer and we can already see how the broth, the water get much clearer already. Once they lightly cooked, we can add the aromatic garnish made of onion, garlic, cloves, pepper and a bouquet garni. In the bouquet garni is leek, celery, thyme and bay leaves.

In this instance, we're also adding champignon de Paris mushrooms, as the important thing in the chicken stock is to add everything that can be aromatic. We could add ginger if we'd like, or other types of mushrooms. I'm not adding tomatoes, nor carrots, as I don't like them and I don't like the sweetness they add.

Once we added the aromatic garnish and the vegetable part, we're closing the lid and allowing it to cook for 4, 5 or even 6 hours, time is relative. The most important thing is to taste. Once we decided, or anyway, we have the feeling the broth reached the most of its taste intensity, we can filter it.

This is the final result. It must be a clear, light broth, but at the same time, tasty, and we'll use it to add it to all of the other sauces we're going to make next. Every morning at Taillevent we prepare fresh sauces.

We're preparing them in the morning for lunch and in the afternoon for dinner, so the idea is exactly to have fresh sauces, made each and every service time. Today we're going to show you how we make at Taillevent our brown base sauce. We're preparing a veal sauce, a roe deer sauce, a lamb sauce and a chicken sauce, and in the smallest container will be wild goose cuttings.

Let's start by heating all of the containers up so we can add the carcasses and meat in to give it straight away a Maillard reaction. What is that? It's just a reaction of caramelization of the surface.

Consequently, we're adding the meat into the cocottes, the pots, without moving it. We aren't mixing straight away, as if we're moving the meat right away, the container cools down and we'd be making boiled meat. The idea is to caramelize perfectly the whole surface of the meat, this is why it is all cut into small pieces, so that the browning of the meat is easier.

Doing this requires attention, attention not to burn the bones and meat, otherwise the result will be bitter. Once the surface, the meat starts caramelizing, we're adding butter, in such quantity so as to cover the meat, so we'll obtain a color that is even more homogeneous. Once the caramelization is on point, we're adding the aromatic garnish.

Garlic, shallot, we're allowing it to caramelize well as a whole, paying attention as we're adding them, because if we're adding them too early, eventually we'll get a burnt shallot and garlic, if we're adding them too late, we'll have burnt meat, so we need to pay attention and add them at the right moment. Only at the end, we'll add the aromatic herbs: rosemary, thyme, sage. Once everything is properly caramelized, we're degreasing it in a strainer, for example.

We're allowing the fat to drip off and we're adding them back into the container, inside the cocotte. We're glazing, mostly de-glazing with vinegar from Jerez to give it sourness. Once the vinegar evaporated and there's only a hint of sour that is not aggressive, we're adding chicken stock, meaning the base I just showed to you before.

The idea is to add it three times. The first time. just a small ladleful and reduce until the fat appears to the surface again.

We'll repeat a second and a third time, because as we do so, we're concentrating taste. Taste is paramount for us in order to get a finished and intense sauce without the need to add liters and liters of water. So, once these three passages are done, we're adding and finishing with a remouille.

What is a remouille? It's simply the sauce we made the day before. We saved the juices and the sauce, and before we throw the bones and meat away, we're adding chicken stock to level and allowing it to cook for about an hour, so as to collect all of the juices and all of the tastes that stuck to the meat.

We're using this base to continue cooking our sauce. Once we covered with this remouille, we're changing the container as we toasted and cooked them in a large container at the beginning. We can see how if we allow them to cook in a wide container, the evaporation is much faster, as a consequence it will reduce much quicker and we'll get the impression it is cooked when, in fact, it isn't.

We're covering it with more broth, if necessary, to level, and one important thing: before it starts boiling, we're de-glazing it, even if we already did it once, it's important to de-glaze it once more otherwise we'd be making an emulsion and we don't want to obtain an emulsion of fat and liquid, what we want is clear liquid. Once it's de-glazed, we're allowing it to cook. It needs to simmer for two-three hours.

We're moving it off the heat and allowing it to infuse with rosemary, with sage, with thyme for some minutes. After this time, we're sifting it through a chinoise and allowing it to cool down at room temperature, if we have time, or in a blast chiller. The liquid goes to the bottom, the remaining fat - there's always some - will rise to the surface, and we're removing this fat.

We're allowing the sauce to reduce until the desired consistency. The base we mostly use to bind sauces is roux. Roux is a base of flour cooked in butter, also used, as it's well known, as a base to bind béchamel.

One interesting thing in Escoffier is that in his recipes for sauces, he already talks about arrowroot. Why is it today so important as a thickener? Because, differently from roux, that can change the color of a sauce, differently from potato starch, that can make a sauce a bit sticky, arrowroot allows us to get a sauce that is clear, but at the same time thick.

At Taillevent, the brown base sauce, or in this case, lamb sauce, is used as a side, for example, for lamb ribs, specifically aromatized with truffle. After showing you chicken stock and the meat brown sauce, we're going to show you another classic of the French kitchen, which is supreme sauce, as a side, for example, for a chicken pie. Supreme sauce is simply chicken stock bound with roux, meaning a velouté that is added with more chicken stock, allowing it to reduce and eventually adding cream.

At the restaurant, I like to simplify this recipe. I like to make a reduced chicken stock with cream that we're going to bind some minutes before service only, using fois gras. Fois gras allows us to bind this sauce and at the same time gives it an aromatic complexity that is much more important than roux.

An interesting thing in Escoffier's culinary guide: talking about sauces, he was always talking about an economical side. It's incredible because it's so current. He used to say roux was introduced in order to bind a sauce, consequently to obtain more quantity, but sometimes lowering its quality.

As a consequence, the analysis we made today, and mostly as far as my cooking is concerned, is that the great mother sauces by Escoffier were modified according to the personality of each cook, because that is what matters to me, to have a base of analysis, a logical base to understand what something is, and then not just make them mechanically, but adding some personality and some logic. I think you could tell by yourself that this topic, the mother sauces, is very wide and deserves an analysis that is much more complex than what we made today. I hope I gave you some material to work on and maybe even answers to some of your doubts.

Greetings, and see you soon to continue this adventure. Ciao!

Related Videos

18:07

The Rossini Tournedos in a 3 Michelin star...

Italia Squisita

2,801,619 views

16:22

Bechamel in a French Michelin Two-Star Res...

Italia Squisita

2,257,718 views

11:35

Seafood Spaghetti with 50 Fish by chef Giu...

Italia Squisita

1,123,526 views

14:27

Lasagna in the oldest Michelin restaurant ...

Italia Squisita

470,146 views

16:34

How to Make a Beurre Blanc (Butter Sauce) ...

Chef Jean-Pierre

631,375 views

16:28

Cordon Bleu and Mashed Potatoes in a Frenc...

Italia Squisita

1,421,227 views

12:54

French Onion Soup in a Michelin French Res...

Italia Squisita

527,349 views

22:58

How Legendary Chef Eric Ripert Runs One of...

Eater

1,476,910 views

13:08

Pasta alla ZOZZONA (con le uova del pollai...

Gambero Rosso

1,025,118 views

28:11

Demi Glace The King of All Sauces | Chef J...

Chef Jean-Pierre

838,785 views

26:22

The Most Precious French Chicken in the 3 ...

Italia Squisita

839,376 views

8:14

La Cottura del Riso nel Mondo Orientale

Cucina con Feng

36,272 views

18:37

Beef Wellington in a 3 Michelin stars Engl...

Italia Squisita

2,502,280 views

11:16

How a Master Chef Runs a 2 Michelin Star N...

Eater

8,165,881 views

13:23

CODA ALLA VACCINARA - Le ricette di Giorgione

Gambero Rosso

634,007 views

23:06

"King of Carbonara" shares his Pasta Recip...

Aden Films

3,638,253 views

19:13

Potato Rösti in a Swiss 2-star Michelin re...

Italia Squisita

440,879 views

14:45

Beurre Blanc Tutorial | using the classic ...

French Cooking Academy

1,606,407 views

9:36

Fettuccine Alfredo - La ricetta di Giorgione

Gambero Rosso

1,628,984 views

22:39

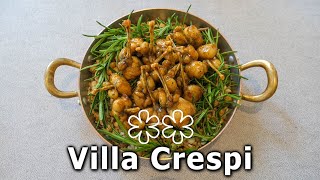

We are back at VILLA CRESPI, the 2 Micheli...

Cosa mangiamo oggi?

1,712,582 views