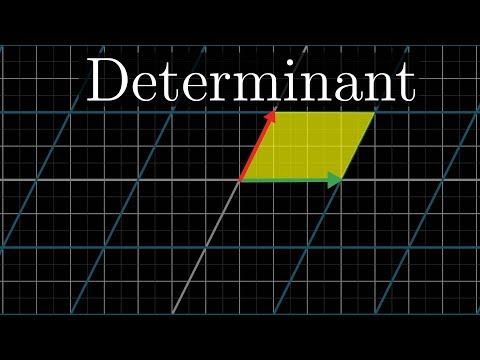

The determinant | Chapter 6, Essence of linear algebra

3.92M views1761 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

The determinant measures how much volumes change during a transformation.

Help fund future projects:...

Video Transcript:

Hello, hello again. So moving forward, I'll be assuming that you have a visual understanding of linear transformations and how they're represented with matrices, the way that I've been talking about in the last few videos. If you think about a couple of these linear transformations, you might notice how some of them seem to stretch space out, while others squish it on in.

One thing that turns out to be pretty useful for understanding one of these transformations is to measure exactly how much it stretches or squishes things. More specifically, to measure the factor by which the area of a given region increases or decreases. For example, look at the matrix with columns 3, 0 and 0, 2.

It scales i-hat by a factor of 3 and scales j-hat by a factor of 2. Now, if we focus our attention on the 1 by 1 square whose bottom sits on i-hat and whose left side sits on j-hat, after the transformation, this turns into a 2 by 3 rectangle. Since this region started out with area 1 and ended up with area 6, we can say the linear transformation has scaled its area by a factor of 6.

Compare that to a shear, whose matrix has columns 1, 0 and 1, 1, meaning i-hat stays in place and j-hat moves over to 1, 1. That same unit square determined by i-hat and j-hat gets slanted and turned into a parallelogram, but the area of that parallelogram is still 1, since its base and height each continue to have length 1. So even though this transformation smushes things about, it seems to leave areas unchanged, at least in the case of that 1 unit square.

Actually though, if you know how much the area of that one single unit square changes, it can tell you how the area of any possible region in space changes. For starters, notice that whatever happens to one square in the grid has to happen to any other square in the grid, no matter the size. This follows from the fact that grid lines remain parallel and evenly spaced.

Then, any shape that's not a grid square can be approximated by grid squares pretty well, with arbitrarily good approximations if you use small enough grid squares. So, since the areas of all those tiny grid squares are being scaled by some single amount, the area of the blob as a whole will also be scaled by that same single amount. This very special scaling factor, the factor by which a linear transformation changes any area, is called the determinant of that transformation.

I'll show how to compute the determinant of a transformation using its matrix later on in this video, but understanding what it represents is, trust me, much more important than the computation. For example, the determinant of a transformation would be 3 if that transformation increases the area of a region by a factor of 3. 40 00:02:57,610 --> 00:02:57,040 The determinant of a transformation would be ½ 41 00:02:58,180 --> 00:02:57,610 if it squishes down all areas by a factor of ½.

The determinant of a transformation would be 1 half if it squishes down all areas by a factor of 1 half. And the determinant of a 2D transformation is 0 if it squishes all of space onto a line, or even onto a single point. Since then, the area of any region would become zero.

That last example will prove to be pretty important. It means that checking if the determinant of a given matrix is zero will give a way of computing whether or not the transformation associated with that matrix squishes everything into a smaller dimension. You'll see in the next few videos why this is even a useful thing to think about, but for now, I just want to lay down all of the visual intuition, which, in and of itself, is a beautiful thing to think about.

Okay, I need to confess that what I've said so far is not quite right. The full concept of the determinant allows for negative values. But what would the idea of scaling an area by a negative amount even mean?

This has to do with the idea of orientation. For example, notice how this transformation gives the sensation of flipping space over. If you were thinking of 2D space as a sheet of paper, a transformation like that one seems to turn over that sheet onto the other side.

Any transformations that do this are said to invert the orientation of space. Another way to think about it is in terms of i-hat and j-hat. Notice that in their starting positions, j-hat is to the left of i-hat.

If, after a transformation, j-hat is now on the right of i-hat, the orientation of space has been inverted. Whenever this happens, whenever the orientation of space is inverted, the determinant will be negative. The absolute value of the determinant, though, still tells you the factor by which areas have been scaled.

For example, the matrix with columns 1, 1 and 2, negative 1 encodes a transformation that has determinant, I'll just tell you, negative 3. And what this means is that space gets flipped over and areas are scaled by a factor of 3. So why would this idea of a negative area scaling factor be a natural way to describe orientation flipping?

Think about the series of transformations you get by slowly letting i-hat get closer and closer to j-hat. As i-hat gets closer, all of the areas in space are getting squished more and more, meaning the determinant approaches 0. Once i-hat lines up perfectly with j-hat, the determinant is 0.

Then, if i-hat continues the way that it was going, doesn't it kind of feel natural for the determinant to keep decreasing into the negative numbers? So that's the understanding of determinants in two dimensions. What do you think it should mean for three dimensions?

It also tells you how much a transformation scales things, but this time, it tells you how much volumes get scaled. Just as in two dimensions, where this is easiest to think about by focusing on one particular square with an area 1 and watching only what happens to it, in three dimensions, it helps to focus your attention on the specific 1 by 1 by 1 cube whose edges are resting on the basis vectors, i-hat, j-hat and k-hat. After the transformation, that cube might get warped into some kind of slanty slanty cube.

This shape, by the way, has the best name ever, parallelipiped, a name that's made even more delightful when your professor has a nice thick Russian accent. Since this cube starts out with a volume of 1, and the determinant gives the factor by which any volume is scaled, you can think of the determinant simply as being the volume of that parallelipiped that the cube turns into. A determinant of 0 would mean that all of space is squished onto something with 0 volume, meaning either a flat plane, a line, or, in the most extreme case, onto a single point.

Those of you who watched chapter 2 will recognize this as meaning that the columns of the matrix are linearly dependent. Can you see why? What about negative determinants?

What should that mean for three dimensions? One way to describe orientation in 3D is with the right hand rule. Point the forefinger of your right hand in the direction of i-hat, stick out your middle finger in the direction of j-hat, and notice how when you point your thumb up, it's in the direction of k-hat.

If you can still do that after the transformation, orientation has not changed, and the determinant is positive. Otherwise, if after the transformation it only makes sense to do that with your left hand, orientation has been flipped, and the determinant is negative. So, if you haven't seen it before, you're probably wondering by now, how do you actually compute the determinant?

For a 2x2 matrix with entries a, b, c, d, the formula is a times d minus b times c. Here's part of an intuition for where this formula comes from. Let's say that the terms b and c both happened to be 0.

Then, the term a tells you how much i-hat is stretched in the x direction, and the term d tells you how much j-hat is stretched in the y direction. So, since those other terms are 0, it should make sense that a times d gives the area of the rectangle that our favorite unit square turns into, kind of like the 3, 0, 0, 2 example from earlier. Even if only one of b or c are 0, you'll have a parallelogram with a base a and a height d.

So, the area should still be a times d. Loosely speaking, if both b and c are non-zero, then that b times c term tells you how much this parallelogram is stretched or squished in the diagonal direction. For those of you hungry for a more precise description of this b times c term, here's a helpful diagram if you'd like to pause and ponder.

Now, if you feel like computing determinants by hand is something that you need to know, the only way to get it down is to just practice it with a few. There's really not that much I can say or animate that's going to drill in the computation. This is all triply true for three-dimensional determinants.

There is a formula, and if you feel like that's something you need to know, you should practice with a few matrices, or, you know, go watch Sal Khan work through a few. Honestly, though, I don't think that those computations fall within the essence of linear algebra, but I definitely think that understanding what the determinant represents falls within that essence. Here's kind of a fun question to think about before the next video.

If you multiply two matrices together, the determinant of the resulting matrix is the same as the product of the determinants of the original two matrices. If you tried to justify this with numbers, it would take a really long time, but see if you can explain why this makes sense in just one sentence. Next up, I'll be relating the idea of linear transformations covered so far to one of the areas where linear algebra is most useful, linear systems of equations.

See you then!

Related Videos

12:09

Inverse matrices, column space and null sp...

3Blue1Brown

2,971,351 views

11:14

The Man Who Solved the World’s Most Famous...

Newsthink

1,062,458 views

17:16

Eigenvectors and eigenvalues | Chapter 14,...

3Blue1Brown

4,989,420 views

27:14

What is Jacobian? | The right way of think...

Mathemaniac

1,926,234 views

1:02:46

Grant Sanderson: 3Blue1Brown and the Beaut...

Lex Fridman

559,488 views

53:17

19. Determinant Formulas and Cofactors

MIT OpenCourseWare

357,405 views

14:12

Dot products and duality | Chapter 9, Esse...

3Blue1Brown

2,607,299 views

10:59

Linear transformations and matrices | Chap...

3Blue1Brown

5,346,021 views

15:57

The Big Picture of Linear Algebra

MIT OpenCourseWare

982,294 views

16:26

Dear linear algebra students, This is what...

Zach Star

1,172,123 views

19:07

Why is the determinant like that?

broke math student

180,162 views

27:07

How (and why) to raise e to the power of a...

3Blue1Brown

2,928,283 views

21:58

How to Design a Wheel That Rolls Smoothly ...

Morphocular

1,717,635 views

9:59

Linear combinations, span, and basis vecto...

3Blue1Brown

5,599,674 views

14:31

Determinant and Elementary Row Operation

Prime Newtons

28,635 views

9:52

Vectors | Chapter 1, Essence of linear alg...

3Blue1Brown

8,902,039 views

16:10

The Puzzling Fourth Dimension (and exotic ...

Numberphile

288,652 views

29:59

Tesla’s 3-6-9 and Vortex Math: Is this rea...

Mathologer

4,127,272 views

31:33

The Oldest Unsolved Problem in Math

Veritasium

12,127,524 views