Backpropagation, step-by-step | DL3

4.77M views2226 WordsCopy TextShare

3Blue1Brown

What's actually happening to a neural network as it learns?

Help fund future projects: https://www.p...

Video Transcript:

Here, we tackle backpropagation, the core algorithm behind how neural networks learn. After a quick recap for where we are, the first thing I'll do is an intuitive walkthrough for what the algorithm is actually doing, without any reference to the formulas. Then, for those of you who do want to dive into the math, the next video goes into the calculus underlying all this.

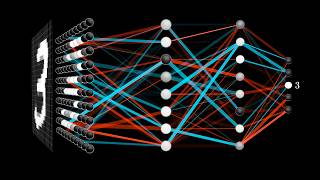

If you watched the last two videos, or if you're just jumping in with the appropriate background, you know what a neural network is, and how it feeds forward information. Here, we're doing the classic example of recognizing handwritten digits whose pixel values get fed into the first layer of the network with 784 neurons, and I've been showing a network with two hidden layers having just 16 neurons each, and an output layer of 10 neurons, indicating which digit the network is choosing as its answer. I'm also expecting you to understand gradient descent, as described in the last video, and how what we mean by learning is that we want to find which weights and biases minimize a certain cost function.

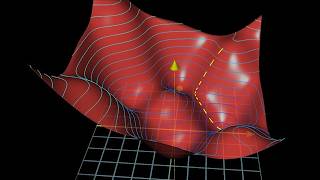

As a quick reminder, for the cost of a single training example, you take the output the network gives, along with the output you wanted it to give, and add up the squares of the differences between each component. Doing this for all of your tens of thousands of training examples and averaging the results, this gives you the total cost of the network. And as if that's not enough to think about, as described in the last video, the thing that we're looking for is the negative gradient of this cost function, which tells you how you need to change all of the weights and biases, all of these connections, so as to most efficiently decrease the cost.

Backpropagation, the topic of this video, is an algorithm for computing that crazy complicated gradient. And the one idea from the last video that I really want you to hold firmly in your mind right now is that because thinking of the gradient vector as a direction in 13,000 dimensions is, to put it lightly, beyond the scope of our imaginations, there's another way you can think about it. The magnitude of each component here is telling you how sensitive the cost function is to each weight and bias.

For example, let's say you go through the process I'm about to describe, and you compute the negative gradient, and the component associated with the weight on this edge here comes out to be 3. 2, while the component associated with this edge here comes out as 0. 1.

The way you would interpret that is that the cost of the function is 32 times more sensitive to changes in that first weight, so if you were to wiggle that value just a little bit, it's going to cause some change to the cost, and that change is 32 times greater than what the same wiggle to that second weight would give. Personally, when I was first learning about backpropagation, I think the most confusing aspect was just the notation and the index chasing of it all. But once you unwrap what each part of this algorithm is really doing, each individual effect it's having is actually pretty intuitive, it's just that there's a lot of little adjustments getting layered on top of each other.

So I'm going to start things off here with a complete disregard for the notation, and just step through the effects each training example has on the weights and biases. Because the cost function involves averaging a certain cost per example over all the tens of thousands of training examples, the way we adjust the weights and biases for a single gradient descent step also depends on every single example. Or rather, in principle it should, but for computational efficiency we'll do a little trick later to keep you from needing to hit every single example for every step.

In other cases, right now, all we're going to do is focus our attention on one single example, this image of a 2. What effect should this one training example have on how the weights and biases get adjusted? Let's say we're at a point where the network is not well trained yet, so the activations in the output are going to look pretty random, maybe something like 0.

5, 0. 8, 0. 2, on and on.

We can't directly change those activations, we only have influence on the weights and biases. But it's helpful to keep track of which adjustments we wish should take place to that output layer. And since we want it to classify the image as a 2, we want that third value to get nudged up while all the others get nudged down.

Moreover, the sizes of these nudges should be proportional to how far away each current value is from its target value. For example, the increase to that number 2 neuron's activation is in a sense more important than the decrease to the number 8 neuron, which is already pretty close to where it should be. So zooming in further, let's focus just on this one neuron, the one whose activation we wish to increase.

Remember, that activation is defined as a certain weighted sum of all the activations in the previous layer, plus a bias, which is all then plugged into something like the sigmoid squishification function, or a ReLU. So there are three different avenues that can team up together to help increase that activation. You can increase the bias, you can increase the weights, and you can change the activations from the previous layer.

Focusing on how the weights should be adjusted, notice how the weights actually have differing levels of influence. The connections with the brightest neurons from the preceding layer have the biggest effect since those weights are multiplied by larger activation values. So if you were to increase one of those weights, it actually has a stronger influence on the ultimate cost function than increasing the weights of connections with dimmer neurons, at least as far as this one training example is concerned.

Remember, when we talk about gradient descent, we don't just care about whether each component should get nudged up or down, we care about which ones give you the most bang for your buck. This, by the way, is at least somewhat reminiscent of a theory in neuroscience for how biological networks of neurons learn, Hebbian theory, often summed up in the phrase, neurons that fire together wire together. Here, the biggest increases to weights, the biggest strengthening of connections, happens between neurons which are the most active, and the ones which we wish to become more active.

In a sense, the neurons that are firing while seeing a 2 get more strongly linked to those are the ones firing when thinking about a 2. To be clear, I'm not in a position to make statements one way or another about whether artificial networks of neurons behave anything like biological brains, and this fires together wire together idea comes with a couple meaningful asterisks, but taken as a very loose analogy, I find it interesting to note. Anyway, the third way we can help increase this neuron's activation is by changing all the activations in the previous layer.

Namely, if everything connected to that digit 2 neuron with a positive weight got brighter, and if everything connected with a negative weight got dimmer, then that digit 2 neuron would become more active. And similar to the weight changes, you're going to get the most bang for your buck by seeking changes that are proportional to the size of the corresponding weights. Now of course, we cannot directly influence those activations, we only have control over the weights and biases.

But just as with the last layer, it's helpful to keep a note of what those desired changes are. But keep in mind, zooming out one step here, this is only what that digit 2 output neuron wants. Remember, we also want all the other neurons in the last layer to become less active, and each of those other output neurons has its own thoughts about what should happen to that second to last layer.

So, the desire of this digit 2 neuron is added together with the desires of all the other output neurons for what should happen to this second to last layer, again in proportion to the corresponding weights, and in proportion to how much each of those neurons needs to change. This right here is where the idea of propagating backwards comes in. By adding together all these desired effects, you basically get a list of nudges that you want to happen to this second to last layer.

And once you have those, you can recursively apply the same process to the relevant weights and biases that determine those values, repeating the same process I just walked through and moving backwards through the network. And zooming out a bit further, remember that this is all just how a single training example wishes to nudge each one of those weights and biases. If we only listened to what that 2 wanted, the network would ultimately be incentivized just to classify all images as a 2.

So what you do is go through this same backprop routine for every other training example, recording how each of them would like to change the weights and biases, and average together those desired changes. This collection here of the averaged nudges to each weight and bias is, loosely speaking, the negative gradient of the cost function referenced in the last video, or at least something proportional to it. I say loosely speaking only because I have yet to get quantitatively precise about those nudges, but if you understood every change I just referenced, why some are proportionally bigger than others, and how they all need to be added together, you understand the mechanics for what backpropagation is actually doing.

By the way, in practice, it takes computers an extremely long time to add up the influence of every training example every gradient descent step. So here's what's commonly done instead. You randomly shuffle your training data and then divide it into a whole bunch of mini-batches, let's say each one having 100 training examples.

Then you compute a step according to the mini-batch. It's not going to be the actual gradient of the cost function, which depends on all of the training data, not this tiny subset, so it's not the most efficient step downhill, but each mini-batch does give you a pretty good approximation, and more importantly, it gives you a significant computational speedup. If you were to plot the trajectory of your network under the relevant cost surface, it would be a little more like a drunk man stumbling aimlessly down a hill but taking quick steps, rather than a carefully calculating man determining the exact downhill direction of each step before taking a very slow and careful step in that direction.

This technique is referred to as stochastic gradient descent. There's a lot going on here, so let's just sum it up for ourselves, shall we? Backpropagation is the algorithm for determining how a single training example would like to nudge the weights and biases, not just in terms of whether they should go up or down, but in terms of what relative proportions to those changes cause the most rapid decrease to the cost.

A true gradient descent step would involve doing this for all your tens of thousands of training examples and averaging the desired changes you get. But that's computationally slow, so instead you randomly subdivide the data into mini-batches and compute each step with respect to a mini-batch. Repeatedly going through all of the mini-batches and making these adjustments, you will converge towards a local minimum of the cost function, which is to say your network will end up doing a really good job on the training examples.

So with all of that said, every line of code that would go into implementing backprop actually corresponds with something you have now seen, at least in informal terms. But sometimes knowing what the math does is only half the battle, and just representing the damn thing is where it gets all muddled and confusing. So for those of you who do want to go deeper, the next video goes through the same ideas that were just presented here, but in terms of the underlying calculus, which should hopefully make it a little more familiar as you see the topic in other resources.

Before that, one thing worth emphasizing is that for this algorithm to work, and this goes for all sorts of machine learning beyond just neural networks, you need a lot of training data. In our case, one thing that makes handwritten digits such a nice example is that there exists the MNIST database, with so many examples that have been labeled by humans. So a common challenge that those of you working in machine learning will be familiar with is just getting the labeled training data you actually need, whether that's having people label tens of thousands of images, or whatever other data type you might be dealing with.

Related Videos

10:18

Backpropagation calculus | DL4

3Blue1Brown

2,978,609 views

18:40

But what is a neural network? | Deep learn...

3Blue1Brown

17,909,252 views

25:06

What is the i really doing in Schrödinger'...

Welch Labs

160,865 views

8:00

What is Back Propagation

IBM Technology

70,575 views

8:48

Large Language Models explained briefly

3Blue1Brown

577,799 views

20:33

Gradient descent, how neural networks lear...

3Blue1Brown

7,240,084 views

17:22

A Proof That The Square Root of Two Is Irr...

D!NG

6,494,191 views

27:14

Transformers (how LLMs work) explained vis...

3Blue1Brown

3,827,896 views

![The moment we stopped understanding AI [AlexNet]](https://img.youtube.com/vi/UZDiGooFs54/mqdefault.jpg)

17:38

The moment we stopped understanding AI [Al...

Welch Labs

1,369,874 views

40:08

The Most Important Algorithm in Machine Le...

Artem Kirsanov

524,897 views

29:42

Why 4d geometry makes me sad

3Blue1Brown

966,670 views

16:40

I never understood why you can't go faster...

FloatHeadPhysics

4,009,527 views

10:00

Simulating Natural Selection

Primer

14,609,677 views

24:07

AI can't cross this line and we don't know...

Welch Labs

1,360,755 views

9:15

I Built a Neural Network from Scratch

Green Code

426,916 views

20:52

What causes the Pauli Exclusion Principle?

Physics Videos by Eugene Khutoryansky

416,507 views

25:28

Watching Neural Networks Learn

Emergent Garden

1,399,915 views

24:02

The Race to Harness Quantum Computing's Mi...

Bloomberg Originals

3,030,225 views

23:01

But what is a convolution?

3Blue1Brown

2,779,334 views