Fake News: Fact & Fiction - Episode 4: Covid-19: Fake news and conspiracy theories

76.86k views2801 WordsCopy TextShare

BBC Learning English

Do you believe everything you see and hear online about the coronavirus pandemic? With the spread of...

Video Transcript:

Hugo: Hello. This is Fake News, Fact and Fiction from BBC Learning English. I'm Hugo.

Sam: And I'm Sam. Hugo: And as you see we're not in the studio today. Like in many parts of the world we're practising social distancing and working from home.

How are you doing there, Sam? Sam: I'm doing OK. Thank you Hugo, but it is definitely a strange world that we're living in right now, isn't it?

And I don't know if you remember but in our first programme we talked about stories going viral, so spreading around the internet really quickly and well now, what we have is a real virus that has gone viral. Hugo: Indeed. And that is going to be the focus of today's programme.

This pandemic has seen a large amount of fake news attached to it. And as we sit at home browsing the internet we may have come across many different stories and theories of the causes of the virus or possible cures. So today we're looking at fake news in the era of Covid-19.

But before we get to that Sam, do you have some vocabulary for us? Sam: Yes I do. So today I'm focusing on some useful vocabulary you might use if you think that what you've seen online is not true.

Red flags are often used as a warning sign. In fact in Britain when motor cars were first used on the streets the law said that you had to have someone walking in front of the vehicle carrying a red flag to warn other road users. These days if a piece of information or a social media post 'raises a red flag' it means you are suspicious that it might be fake news.

There are many red flags to watch out for. For example a post that says something like 'the media doesn't want you to know this' or maybe it's a meme or a quote that claims that a politician you don't like has said or done something terrible. These posts might be easy to share or they might even say 'you must share this!

' or 'share this if you agree'. Those are some examples of red flags that could make you doubt how true the information is. We all like to share things and we all like it when things we share are liked.

But before you hit that share button it's a good idea to fact-check the information the verb fact-check, first used in the 1970s, simply means to check the facts to confirm that the information is true. There are quite a few fact- checking websites which can help you to verify, prove, or debunk, disprove, the information. Debunk, a verb from the 1920s, means to prove or demonstrate that something is not true that it is completely false.

So fact- checking can help you to debunk false claims made on social media. Now you might be wondering, as there is a word debunk, is there a word bunk? Well yes there is but it's not a verb it's a noun.

Bunk and also bunkum are words that mean nonsense. Interestingly they are political in origin and come from the county of Buncombe in the United States. This county was represented by a politician who talked a lot without saying anything important.

So he talked bunkum. Now back to the studio. Hugo: Very interesting Sam, it certainly wasn't bunkum but there was a piece of fake news there wasn't there?

'Back to the studio'? Sam: Yes, well spotted. I did record that section before I knew that we would be filming from home for this episode so I hope you will forgive me for that.

Hugo: Of course, now this pandemic has been dominating the news for a long time now and there are many legitimate areas of discussion to do with restrictions of movement, testing, treatments and the economy. Sam: But we've also seen a lot of different theories about the virus which are not supported by any evidence but which many people have still shared . Some of these are what are known as conspiracy theories.

Hugo: And examples of conspiracy theories are that the earth is flat or that the moon landings were fake and even though these theories are comprehensively debunked some people still strongly believe them. To find out more about conspiracy theories we spoke to Professor Joe Uscinski. He's an associate professor of political science at the University of Miami and the author of the book 'Conspiracy Theories, a Primer'.

We asked him first to define the term conspiracy theory and why people believe them. A conspiracy theory is an allegation or an idea that a small group of powerful people are working in secret to effect an event or circumstance in a way that benefits them and harms the common good. And further this theory hasn't been confirmed by the people we would look to to confirm such events.

There is nothing new about conspiracy theories and you can find them if you look through almost any historical document. So for example the United States Declaration of Independence has a few paragraphs about politics. But then once you read beneath that, it's largely a list of conspiracy theories about the king of England.

So they exist amongst all people at all times. They're very much a human constant. People like to have their ideas make sense when in combination with each other.

So in order for someone to adopt a conspiracy theory that theory has to match with what they already believe. So for example if you really like President Obama, you're probably not going to think that he faked his birth certificate to illegally become president. If you really like President Bush, you're not going to buy the theory that he blew up the Twin Towers on 9/11.

So people's conspiracy theories have to match their underlying world views that they already carry with them so that's why people's conspiracy theories tend to match their political persuasion whether they're liberal or conservative and they have to match their other world views too. So for that reason it's actually more difficult to convince people of conspiracy theories than you might think. Hugo: So we only really buy into a conspiracy theory if it's in line with what we already think about the world.

Sam: Yes and that ties in with a lot of the fake news research doesn't it? So people will share things they believe to be true or want to be true because the ideas match with their own political or ideological views. I'd also like to mention the phrase 'buy' or 'buy into' which he and you Hugo just used.

So these both mean to believe or accept that something is true and you can use the phrase 'I don't buy it' if you are not convinced that something is true. So for example, I heard somewhere that eating lemons can cure coronavirus but I don't buy it. Hugo: Absolutely.

Now let's take a trip around the world. We spoke to a number of our BBC colleagues across the globe to find out what kind of fake news and conspiracy theories related to Covid-19 have been shared on different continents and apologies in advance for the quality of the line in some cases Here in Afghanistan at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis a mullah in the west off the country, in Herat, compared the number of fatalities in Muslim countries with the number of deaths in Western countries and after that said that these numbers showed us the Covid-19 and coronavirus does not kill Muslims. But he was absolutely wrong.

Nowadays we see the number of deaths in Muslim countries and here in Afghanistan is rising day by day. We have received a video and some content with some links to internet, to some documents and so on, saying that the virus has been created by U. S.

scientists who have helped Chinese scientists in Wuhan. But, less than two weeks later we have received another video and other video in the same line, on the same topic saying that the virus has been created by Chinese helped by French scientists. But what was worse is that it's roughly the same images.

The same images that they're giving as evidence of the of fraud. This shows clearly that it's a fake. Here in Brazil there are a lot of messages on WhatsApp and other social media showing photos and videos of people opening up coffins in cemeteries and showing them full of stones.

And they use this to support the conspiracy theory that people are like, increasing the number of deaths artificially just to create problems to our president, you know. There are a lot of these messages with these images to support this idea that this situation is created to, to hurt him politically. But these images are from like a case two years ago in a city in Sao Paulo state, in the country, that was like, a fraud, to insurance you know, like two years ago.

So yeah this is one of the things that are happening here because of the pandemic. Here in Hong Kong. I've heard many theories and you can always find the most confidential intelligence in my mother's mobile phone.

There was a time I received an urgent call from her only to find that she started reading a WhatsApp message to me that was about how the U. S. military smuggled coronavirus to Wuhan in order to destroy China's fast growing economy.

Of course that was absolutely groundless. However the message was circulated widely in her social circle. They are patriots who tend to believe any conspiracy theories targeted at the U.

S. authority. So even if I could convince her that the information was fake this time she would only send me another one next time.

It's just unstoppable. Hugo: So we hear there some typical examples of fake news such as real photographs being deliberately mis-described and examples of the kind of belief in conspiracy theories Professor Uscinski was talking about. Sam: Yes and we hear that people want to share these theories because they have a negative view of a particular country and are happy to believe almost anything negative they hear about them.

I'd also like to pick out a particular word that Billy Chan used. He used the word 'groundless' to refer to some claims. 'Groundless' means not based on any evidence.

There's no proof for it. Hugo: So there we had some insights from around the world. Let's look closer to home now we're joined by our BBC colleague Marianna Spring.

Thanks for being with us. So if you can just explain the work you do here at the BBC first. Marianna: Yes, so I am the specialist disinformation reporter which means that me along with a team at BBC Trending who are part of the World Service and BBC Monitoring and BBC Reality Check.

And so we investigate misleading posts as well as looking to tell the stories of the people who fight and spread misinformation across the world. Hugo: So you must be really really busy. Is it your feeling that from what you've seen that disinformation, conspiracy theories about Covid-19 are very different around the world?

Marianna: I think this pandemic is particularly interesting because most of the misleading stuff we've seen has actually been incredibly global. So there was one particularly viral case that we tracked, a list of dodgy medical myths and tips, and it hopped from the Facebook page of a man in the U. K.

to Facebook groups for Catholics living in India to the Instagram account of a Ghanaian television presenter. So this stuff really goes global and is attributed to a range of different people, to hospitals, professors doctors in the US, in Africa in Europe. There's no limit to to who it can be who is alleged to have started or spread the rumour.

However. I do think there are also specific instances of conspiracy theories or misleading information that are specific to certain countries. In other places, for instance in the U.

K. there's been a conspiracy theory relating to 5G suggesting that 5G technology could perhaps be linked to coronavirus and the spread of it. Those claims are totally false.

But I think because here in the U. K. we've been talking lots about 5G technology and how it will be rolled out they've felt relevant.

And then in other countries across the world there are specific home remedies or suggestions, for instance in China or Vietnam, which have caused harm to people because they believed they would prevent or cure coronavirus. Hugo: And how can we in the mainstream media help particularly in a time when we're being attacked, we're not always trusted by people? Marianna: I think there are two crucial things that we can do to cover this area for different audiences.

The first one is not just to show our answers but to show the workings. So when we reveal that something is false or misleading we don't just put that assertion out there. We also show how we reach that point.

We show how we investigated a specific post or specific claims and why they're untrue. And I think that's a really good way of letting people into how we operate and actually gaining their trust. And secondly I think it's crucial to educate audiences in how they can both spot and stop misleading stuff spreading online.

So there are certain red flags that we look out for when we see something online that makes me think "Oh that looks a bit suspicious". One of them will be these introductions I've mentioned where a friend's brother's cousin's uncle who's a doctor in New York has said something or other. If we see an introduction like that it's probably not right and you need to get to the bottom of who that information has come from.

And also often posts will say 'you must read this - you must share it' in capital letters or mismatched fonts and that can also be another sign that something might be misleading. Another key thing that we look out for are posts that play on our emotions, often boring, often accurate information is actually a bit more boring and it's the stuff that makes us angry or or even happy that seems to give us answers we were looking for that tends to be misleading. So that sort of leads around to to our top tips for stopping the spread which which are essentially that we just need to pause and think and reflect before we share anything and repeating that message to audiences is incredibly important in terms of stopping and tackling the spread of misleading stuff online.

Hugo: Fascinating. Marianna Spring. Thanks for being with us.

Marianna: Thank you. Hugo: So Sam, anything you'd like to pick up from what Marianna just said? Sam: Yes.

She said lots and lots of interesting things but I'll only focus on two. She used the word 'misleading' a couple of times. So 'misleading' is basically something that is trying to make you think a certain way but isn't telling you all of the facts.

The other word she used was 'dodgy'. So this is basically something that is suspicious. You can't really trust it.

It's quite an informal word and it's an adjective. Hugo: Thanks Sam, well that's about all we have time for. But before we go, Sam please remind us of today's key vocabulary.

Sam: Of course. So today we looked at the phrase 'to raise a red flag'. This is used when something about a post or a meme or an image for example makes you think that it might not be true or that it might be fake news.

The verb 'to fact-check' is the process of checking the facts so trying to find out if something is true or not. If you 'debunk' something you show that it's not true. And if you 'verify' something you show the opposite.

So you show that it is true. If you 'buy' or 'buy into' something, it means that you believe it. You think it's true.

If something is 'groundless', it has no evidence to support it. Then we looked at 'misleading' which is something that makes you think a certain way even though maybe it doesn't present all of the facts. And something 'dodgy' is something that is suspicious, maybe not trustworthy.

Hugo: Thank you very much Sam and thank you for watching this special at home version of Fake News, Fact and Fiction. Until next time, goodbye and stay safe. Sam: Bye bye everyone.

Related Videos

10:58

Fake News: Fact & Fiction - Episode 3: Inf...

BBC Learning English

98,276 views

12:21

Fake News: Fact & Fiction - Episode 5: Why...

BBC Learning English

38,522 views

27:11

You're Probably Wrong About Rainbows

Veritasium

3,433,768 views

9:47

9/11 Conspiracy Theories | Jack Dee: So Wh...

Jack Dee

274,626 views

9:45

Hear Arnold Schwarzenegger's prediction ab...

CNN

6,452,752 views

17:44

Conspiracy Theories and the Problem of Dis...

TEDx Talks

262,823 views

10:40

Fake News: Fact & Fiction - Episode 2: Whe...

BBC Learning English

38,951 views

13:42

Brexit: EU red tape will cost small busine...

LBC

32,019 views

1:15:28

We can split the atom but not distinguish ...

Big Think

521,760 views

1:23:07

Ricky Gervais: Comedy, Football and Brothe...

The Overlap

2,291,465 views

18:02

Strange answers to the psychopath test | J...

TED

24,459,154 views

38:21

The hackers and the social media influence...

BBC World Service

449,552 views

36:05

Should I have children? - CrowdScience, BB...

BBC World Service

421,672 views

13:03

Just because it's a conspiracy doesn't mea...

TEDx Talks

444,113 views

15:24

7 Signs of Undiagnosed Autism in Adults

Autism From The Inside

1,634,431 views

7:03

Why it’s so easy to fall for fake news and...

CBC News

73,937 views

7:46

South Korea's martial law crisis: BBC Lear...

BBC Learning English

7,326 views

18:36

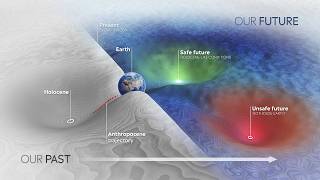

The Tipping Points of Climate Change — and...

TED

990,666 views

17:13

Overtourism: How to be a responsible touri...

BBC World Service

1,129,814 views

8:42

Fake News: Fact & Fiction - Episode 1: The...

BBC Learning English

65,907 views