Best Short Strangle Adjustments: 3 Short Strangles

154.46k views3250 WordsCopy TextShare

tastylive

Subscribe to our Second Channel: @tastylivetrending

Check out more options and trading videos at www...

Video Transcript:

[Music] Hey everyone, welcome back to the show. My name is Mike, this is my whiteboard, and today we're going to be talking about our miniseries on adjustment. Again, we're going to actually look into strangles today.

So we're going to look at the opening trade, we're going to look at some things that can happen throughout the trade, maybe an increase in implied volatility, or maybe a decrease in the stock price, or maybe both. We're going to analyze what we can do to move our break-evens to our benefit and also give us a better chance to be successful in the long run. So let's look at the first opening trade.

Just to recap, what a strangle is, it's really just selling two out-of-the-money options, specifically an out-of-the-money put and an out-of-the-money call, together at the same time in the same expiration cycle. What this does is it creates a profit zone between these short strikes, because if I have a short put, that is a bullish assumption, and I sell a short call, which is a bearish assumption, both of these assumptions are going to battle each other, but it creates a profit zone within the strikes. So anywhere between these strikes, 70 and 90, as long as the stock price expires there, then at expiration, these options are going to stay out of the money; they're not going to have any intrinsic value at all, and they would expire from my account.

They would disappear, and I would be able to keep that credit I originally received. When we're looking at this trade specifically, I've got a $150 credit, let's say, and let's say that I'm looking at an expiration of a perfect 45 days till expiration. You’ll hear that often on TastyTrade, that we're looking for that 40 to 45 days till expiration window, and that's because that is the time frame that gives us the best P&L per day when we're selling premium.

So that's why we always go to that 40 to 45 days till expiration mark. So let's say I've got this perfect setup where I'm collecting a $150 credit and I have 45 days to go, which means if I'm collecting a $150 credit, my max profit on this trade is going to be $150. Again, when we’re talking about option contracts, if I'm selling a one lot, which means I'm just selling one put and one call to create this strategy, I have to multiply my credit of $150 by 100 because one option contract has a theoretical equivalent or theoretical control of 100 shares of stock.

So I always need to take that $150 value and multiply it by 100 to see what my max profit would really be in real-world terms. Since I'm selling a short call, my max loss is considered to be unlimited. Of course, a stock can only go to zero; it can't go past zero.

So on the downside, I do have sort of a defined risk. My stock can't go past zero, so I can't lose more than my downside break-even if the stock does go to zero, which would be 68. 50.

All I did there to calculate that is take my $150 credit and move it over from my short strike. Since we’re selling premium, that’s always going to help our break-even because we can use that credit we collected to offset any losses we might see with a strike that’s in the money. So when I’m looking at the short premium of $150 to calculate my break-evens here, I’m just taking $150 and subtracting it from 70 to get 68.

50 on the downside, and on the upside, I’m actually adding the $150 because when we’re looking at a short call, that’s equivalent to short shares. So if I’m selling $150 worth of credit, I just add it onto there because my losses are going to start coming up here as opposed to a put, where they would be realized below the strike price. My break-even then is 68.

50 and 91. 50 on this trade, and my max loss is unlimited. Again, because there is no cap to where the stock can go; a stock can’t go below zero, but it can go to 100, 200, 300, so there’s no cap on the upside here, which is why we list our max loss as unlimited.

Now, let’s go to the next slide and we’ll talk about an aspect of the trade that is often overlooked, and that is implied volatility increasing. One opportunity that we have when we’re seeing marked losses, specifically with this trade, is that it gives us an opportunity to scale into that. So when we’re talking about trading and lot sizes, maybe you’ll hear Tom refer to it as a tranche; really what we’re talking about is segments of our overall contract size.

So if I said if I’m able to trade maybe a five lot, let’s say my default size is a five lot. Instead of going all five contracts at once into this trade, maybe I would look to deploy two at once, and then maybe another two, and then maybe one, or maybe three at first and then another two. What that does is it gives me a lot more flexibility to manage this trade in a much better way.

So let’s take a look at this one when we’re talking about an implied volatility increase. So I’ve got my original trade listed here, where I’m collecting a $150 credit. I'm selling an out-of-the-money put and also an out-of-the-money call, and these strikes are at 70 and 90.

When implied volatility increases, all that is doing is reflecting what’s happening in the option price market. So if implied volatility is. .

. Increasing that means that the option prices have increased as well. So what that means is that I can probably go farther out in time, or actually in the same expiration, I can go farther out in terms of strike prices and collect that same credit.

If we think about implied volatility as the bell curve—we see it on the Do Trade page—if implied volatility increases, you're going to see the bell curve widen out. That's because the probabilities are going to be correlated with the chances of a stock price reaching that strike. So, if implied volatility is increasing, what that essentially means is that the stock price has a chance to go up even higher or down even lower, because implied volatility is just looking at the range of where a stock price may go, or the one standard deviation range where the stock price may go over one year's time.

So, if implied volatility is increasing, you're going to see the probabilities also increase on those further-out strikes, but the prices of those options should increase as well. So, what does this mean for us? What this means is that instead of just layering on another trade on these same strikes—sure, we could totally do that.

If I did that, scaling into implied volatility, I would probably collect more than a $150 credit if I stuck with these same strikes. But what I wanted to illustrate here is, if 5 days pass and we see implied volatility has increased significantly, which would show me a marked loss on this trade, because if the option prices have increased (if I sold them here), option prices have increased, then I'm going to see a marked loss. When we're selling premium, we want the prices to decrease so we can buy back that spread for a lower price to reap those profits.

But if implied volatility has increased, that's indicating that the option prices have increased. So, maybe a different way we can scale into this is by looking to collect the same credit, and in doing so, we're able to move much further out. So, as you can see, I can move my call three points further out, and I can also move my put three points further out, and let's say that's giving me that $150 credit that I'm looking for.

So, how does this affect all of these values down here? Well, number one, my max profit is going to be $3 now because I have two contracts. Now I've got two strangles on.

While they do have different strikes, at the end of the day, I still have two strangles. My break-even is going to benefit because I'm collecting that additional $150. My break-evens now move to my short strikes here.

You might be thinking to yourself, “Well, if I'm collecting this premium, shouldn't my break-evens be further than these strikes? ” Well, normally it would, if we were selling the same strikes here. If I was selling the same strikes of 90 and 70, then my break-even would be further out here.

But since I'm moving my strikes out, which gives me a higher probability of profit on this specific trade, what we need to do is consider the fact that yes, my break-even was originally 91. 50 up here, so if the stock price goes to 93 on this trade, I would see a $150 loss, and I would be collecting $150 here. So, if I have a $150 loss on this trade and I've collected $150 here, my real break-even, if I have both of these trades on, is going to be right at this short strike.

So, 93 on this side and 67 on that side. My max loss is still unlimited. Again, the stock price can't go below zero, but a stock can go well above the strikes you have listed here, so the loss is still considered to be unlimited because we don't have that defined risk on the call side or the defined risk on the put side.

One important thing to note, though, is that now instead of having a one lot of this strangle, I now have a two lot with different strikes. So, if the stock price does end up going past these strikes, we're going to see the losses accelerate to 2x the speed we would normally see if we just had the one contract. But if I'm able to trade up to five contracts in my personal portfolio, then being able to scale into this implied volatility increase is going to give me a much better chance to be successful in the long run.

Another important note on this specific adjustment is that my max profit is going to be realized still if my stock price is between 70 and 90. As we know, our break-evens are at 93 and 67. So, if the stock price ends up anywhere between 90 and 93, we're going to be able to realize a profit, but less than that max profit here.

So, their max profit is still going to be when the stock price is between 70 and 90, because that's when all four of these contracts would be able to expire worthless. Let's go to the next slide, and we'll look at a totally different example, and we're going to look at if the stock price goes down. So, again, we have our original trade here, but what happens if over about 20 days, the stock price goes from 80 to 69?

So, what we've shown to do on TastyTrade, and what we've shown has been profitable with our back test from the research team, is to move the strike down—so move the untested strike down. If you ever wonder what the untested or tested strike is in. .

. This specific example, the put strike would be the tested strike because the stock price has gone from being in the middle here, going all the way down to the put strike, which is now being touched. So the put side is going to be the tested side, and since the call side is going to be the profitable side, it's going to be the untested side.

That's another way to think of it: whichever side is the losing side of a neutral strategy is going to be that tested side, and whatever side is going to be the winning side is going to be the untested side. So, let's say we close out this call here and we roll it down to the 81 strike for a 45-cent credit. Since I have 26 days to go, I might want to stay in the same cycle.

We have shown that when we're getting down to the expiration, maybe there's seven or ten days; maybe that's when I would move my strikes out in time. But if I'm able to capture a credit just by moving my strike down here, then maybe I would stay in the same expiration cycle. It's also important to assess my assumption as well.

So do I think the stock price can get back in between this range in 26 days? Personally, I would say sure because it's right now at 69 and my strikes are at 70 and 81 now, which is really important to understand when it comes to my break-even. So, if we look at the credit we received of 45, of course we would add that on to our original credit of $150 to bring our new max profit to $1.

95. However, our new max profit is not realized if the stock price is between 70 and 90 anymore because we rolled our call down; we closed out the 90 strike and rolled it down to 81. So, for us to realize this new max profit of $1.

95, I need the stock price to be between 70 and 81. It can be at 70 or 81; as long as it's not one penny in the money, both of these options would expire worthless, and we would realize that max profit of $1. 95, which is just a summation of the credit we've received.

When we look at our break-evens on our downside, we're actually benefiting from this trade from this roll here because our new max profit and our total credit is $1. 95. I can now subtract that from the put strike, which brings my break-even on the downside all the way down to 60.

805. Since we rolled our call side down from 90 to 81, our break-even is no longer in the '90s. It's important to realize that our break-even is now at $82.

95, and all I did there was take my total credit of 45, add that to the $150 credit I originally received, and then just add that to my strike price here. My max loss is still unlimited because, again, we are not defined risk, especially to the upside. This is just a close out of the 90 call, so we don't have a spread here.

We're just moving our short call down, and now we have a strangle at 70 and 81, as opposed to 70 and 90. But since we were able to collect a credit and increase our max profit and move our break-even down past where the stock price is even further than that, this is a nice adjustment to make, especially when we're tested on one of the sides. So, we've got a situation where the stock price or the strike price was tested.

We also have a situation where we scaled into implied volatility. Let's see what we can do on the next slide if we combine those things. So we've got a combination of those things, and we're looking at only seven days to go.

So at this point, what I'm really going to do is assess what I think about this trade. I've got the stock price actually at 70 instead of 69, so it's sitting right on my short put. One thing that I might want to do is capture the profit that I originally received on the trade.

If my assumption has changed, or if my assumption is still the same—that it's going to stay pretty range-bound—or the stock price is going to stay range-bound and implied volatility has increased so much, I'm looking around on the trade desk and I can see that with the order chains I'm looking at a straddle, comparing it to a strangle. I can see that I can keep, or I can roll my put out in time to a new 45 days till expiration cycle, and I can also sell a call on the 70 strike in the 45 days till expiration cycle. I can collect a whopping $6 credit.

So, the stock price is trading at 70; I can collect a $6 credit because implied volatility is so high. So maybe I would go ahead and assess my position. If I think it's still going to be range-bound and I still want to be in this position, maybe I would look to sell a straddle instead of a strangle.

We know that straddles are going to best take advantage of an implied volatility contraction because when we look at that bell curve of the probabilities, it's also pretty inherent of where the extrinsic value is. The most extrinsic value is right in the at-the-money strikes, and when we know intrinsic value is just a reflection of implied volatility and time, if we see an IV contraction, we should see those middle strikes contract the most. So maybe I would look.

. . To create a new trade where I'm collecting a $6 credit, I now have a break-even of 64 and 76.

I'm just taking that credit and moving it to the downside to determine my downside break-even and adding it to that 70 strike and 70 stock price to determine my upside break-even. However, my max loss here is still unlimited because it is an undefined risk trade. So, let's wrap all this together with some takeaways for you.

The first takeaway is that IV expansion can create opportunities even when we see marked losses. We hear this all the time, especially on the support desk. When implied volatility increases, or maybe a position just shows a loss even when the stock's strikes have not been breached, that may be an opportunity to scale into that.

If implied volatility has increased, it may give us a better chance to be successful if we're selling premium in a higher environment than we were before. Another thing to take away is to always be aware of the break-even. We saw that when we rolled that call strike down, we moved the break-even pretty significantly.

Although we did adjust our break-even to the downside quite nicely, we did move our break-even on the upside down about nine points, so it's important to consider that. Lastly, if we're getting to the tail end of a trade, it's important to reassess our assumption and decide whether we want to stay in that trade or get out and move our capital elsewhere. So, thanks for tuning in.

This has been three short strangle adjustments; hopefully, you enjoyed it! If you've got any questions or feedback at all, shoot me an email here, or you can tweet me at DoTraderMike. We've got Jim Schultz from Theory to Practice coming up next, so stay tuned.

Hey everyone, thanks for watching our video! If you liked this video, give it a thumbs up or share it with a friend. Click below to watch more videos, subscribe to our channel, or go to our [Music] website.

Related Videos

14:40

Vertical Debit Spreads 101

tastylive

143,979 views

17:06

How I Would Manage a Short Strangle Moving...

tastylive

27,638 views

14:28

We Compared This Dip To 2008... The Simila...

tastylive

13,114 views

52:56

The BEST 0DTE Strategies for Profit with T...

OptionsPlay

81,313 views

22:09

How He Trades Full Time with ONE Strategy

tastylive

198,234 views

31:31

How This Professor Unlocked a Winning 0 DT...

tastylive

84,082 views

35:53

Building An Option Portfolio (without over...

tastylive

69,652 views

17:19

The Top 3 0 DTE Options Trading Strategies

SMB Capital

273,132 views

18:10

How do we choose which underlying to trade?

tastylive

155,377 views

12:01

Selling Put Options in $10,000 (or less) T...

tastylive

464,915 views

53:15

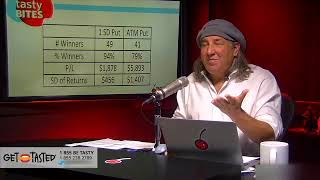

Tom Sosnoff | Option Trading Strategies w...

The Investor's Podcast Network

32,171 views

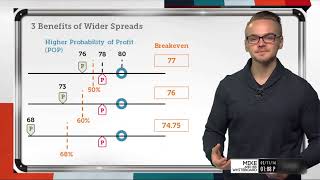

15:43

Wider Options Spreads: 3 Benefits | Option...

tastylive

87,342 views

57:33

You'll NEVER Buy Stocks Again: Deep in the...

OptionsPlay

77,053 views

10:58

How to Manage Your Deltas In Options Trading

tastylive

16,670 views

1:03:02

The Blueprint to Tom Sosnoff's Ideal Portf...

tastylive

65,616 views

50:18

Every Options Strategy (and how to manage ...

tastylive

52,225 views

26:05

How to Build Wealth with Covered Calls, Di...

tastylive

47,910 views

47:44

Ranking Option Strategies Based On Risk | ...

tastylive

73,786 views

22:55

The 5 Deadly Covered Call MISTAKES (which ...

SMB Capital

254,520 views

32:17

Trader With 1.7 Mil Returned Explains His ...

tastylive

26,807 views