I've got several fun things for you this video. An unsolved problem, a very elegant solution to a weaker version of the problem, and a little bit about what topology is and why people care. But before I jump into it, it's worth saying a few words on why I'm excited to share this solution.

When I was a kid, since I loved math and sought out various mathy things, I would occasionally find myself in some talk or a seminar where people wanted to get the youth excited about things that mathematicians care about. A very common go-to topic to excite our imaginations was topology. We might be shown something like a mobius strip, maybe building it out of construction paper by twisting a rectangle and gluing its ends.

Look, we'd be told, as we were asked to draw a line along the surface. It's a surface with just one side. Or we might be told that topologists view coffee mugs and donuts as the same thing, since each has just one hole.

But these kinds of demos always left a lurking question. How is this math? How does any of this actually help to solve problems?

It wasn't until I saw the problem that I'm about to show you, with its elegant and surprising solution, that I started to understand why mathematicians actually care about some of these shapes and the properties they have. So, there's this unsolved problem called the inscribed square problem. If you have a closed loop, meaning you squiggle some line through space in a potentially crazy way and you end up back where you started, the question is whether or not you'll always be able to find four points on this loop that make up a square.

If your closed loop was a circle, for example, it's quite easy to find an inscribed square. Infinitely many, in fact. If your loop was instead an ellipse, it's still pretty easy to find an inscribed square.

The question is whether or not every possible closed loop, no matter how crazy, has at least one inscribed square. Pretty interesting, right? I mean, just the fact that this is unsolved is interesting, that the current tools of math can neither confirm nor deny that there's some loop with no inscribed square in it.

Now, if we weaken the question a bit and ask about inscribed rectangles instead of inscribed squares, it's still pretty hard, but there is a beautiful, video-worthy solution that might actually be my favorite piece of math. The idea is to shift the focus away from individual points on the loop and instead onto pairs of points. We'll use the following fact about rectangles.

Let's label the vertices of some rectangle ABCD. Then the pair of points AC has a few things in common with the pair of points BD. The distance between A and C equals the distance between B and D, and the midpoint of A and C is the same as the midpoint of B and D.

In fact, any time you have two separate pairs of points in space, AC and BD, if you can guarantee that they share a midpoint and that the distance between AC equals the distance between B and D, it's enough to guarantee that those four points make up a rectangle. So what we're going to do is try to prove that for any closed loop, it's always possible to find two distinct pairs of points on that loop that share a midpoint and which are the same distance apart. Take a moment to make sure that's clear.

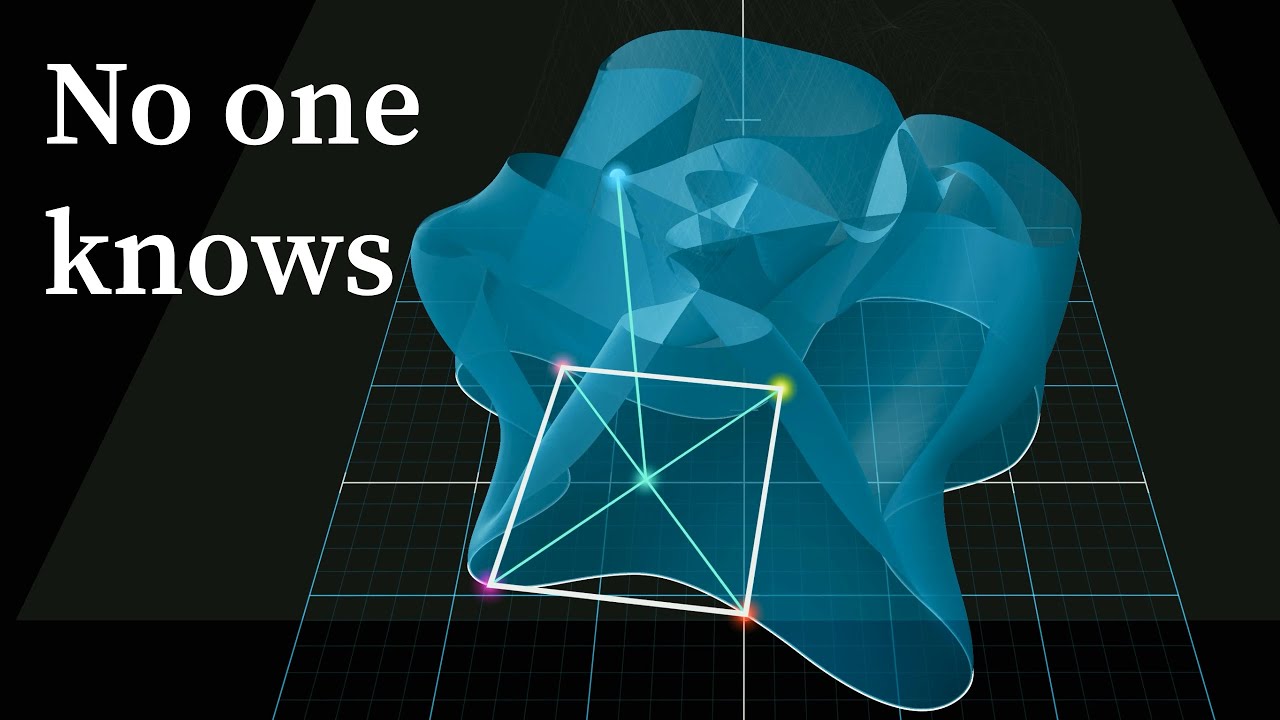

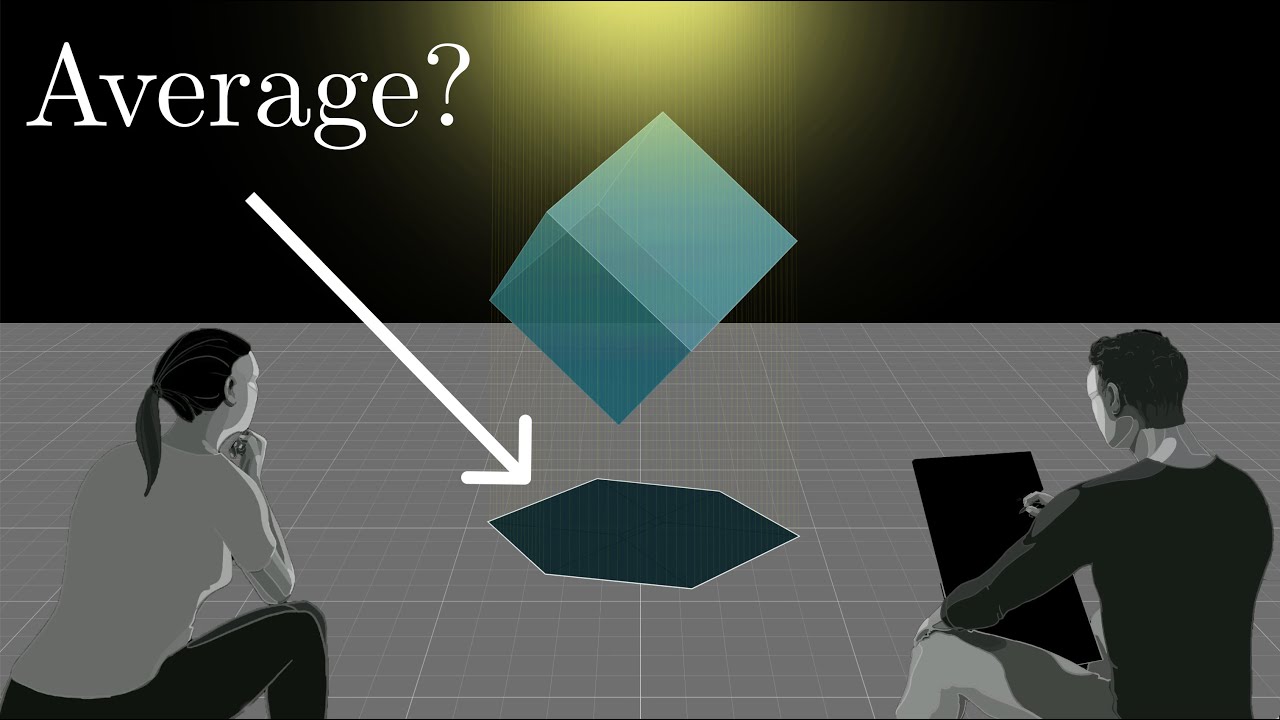

We're finding two distinct pairs of points that share a common midpoint and which are the same distance apart. The way we'll go about this is to define a function that takes in pairs of points on the loop and outputs a single point in 3D space, which kind of encodes the midpoint and distance information. It will be sort of like a graph.

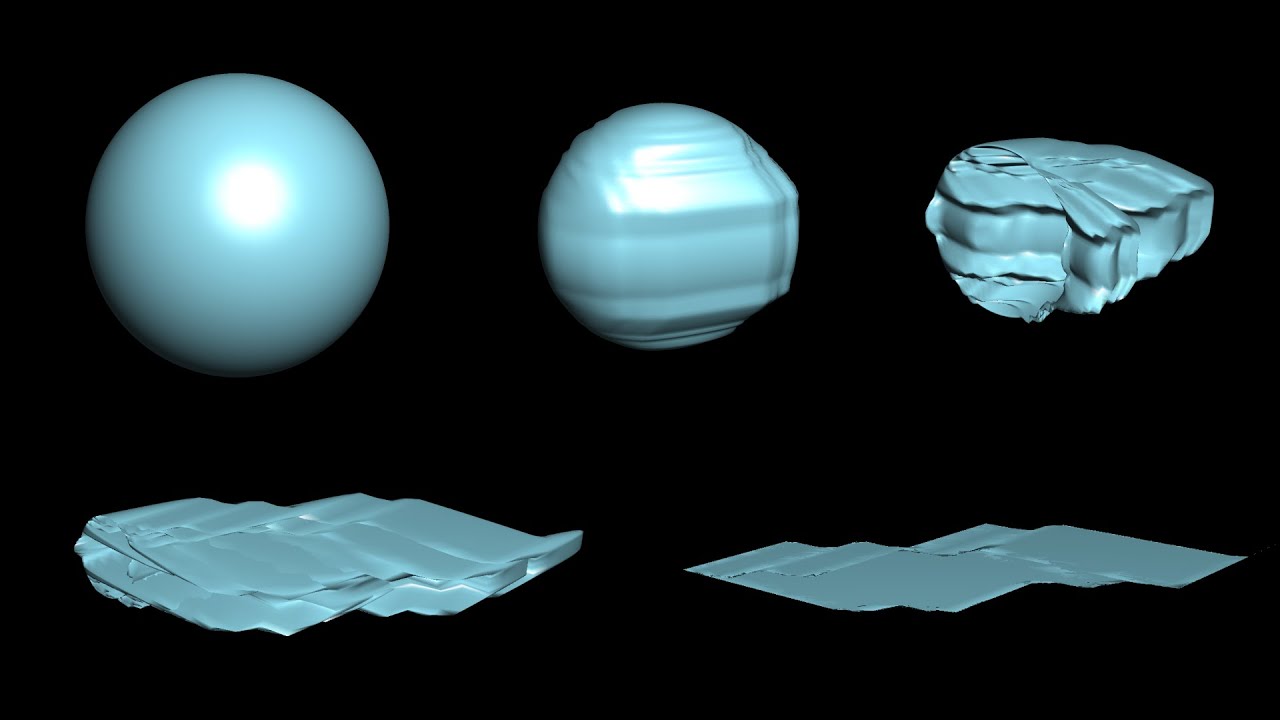

Consider the closed loop to be sitting on the xy-plane in 3D space. For a given pair of points, label their midpoint m, which will be some point on the xy-plane, and label the distance between them d. Plot the point, which is exactly d units above that midpoint m in the z-direction.

As you do this for many possible pairs of points, you'll effectively be drawing through 3D space. And if you do it for all possible pairs of points on the loop, you'll draw out some kind of surface above the plane. Now look at the surface, and notice how it seems to hug the loop itself.

This is actually going to be important later, so let's think about why it happens. As the pair of points on the loop gets closer and closer, the plotted point gets lower, since its height is by definition equal to the distance between the points. Also, the midpoint gets closer and closer to the loop as the points approach each other.

Once the pair of points coincides, meaning the input of our function looks like xx for some point x on the loop, the plotted point of the surface will be exactly on the loop at the point x. Okay, so remember that. Another important fact is that this function is continuous, and all that really means is that if you slightly adjust a given pair of points, then the corresponding output in 3D is only slightly adjusted as well.

There's never a sudden discontinuous jump. Our goal, then, is to show that this function has a collision, that two distinct pairs of points each map to the same spot in 3D space. Because the only way for that to happen is if they share a common midpoint, and if their distance d apart from each other is the same.

So in some sense, finding an inscribed rectangle comes down to showing that this surface has to intersect itself. To move forward from here, we need to build up a relationship with the idea of pairs of points on a loop. Think about how we represent pairs of real numbers using a two-dimensional coordinate plane.

Analogous to this, we're going to seek out a certain 2D surface which naturally represents all pairs of points on the loop. Understanding the properties of this surface will help to show why the graph that we just defined has to intersect itself. Now, when I say pair of points, there are two things that I could be talking about.

The first is ordered pairs of points, which would mean a pair like AB would be considered distinct from the pair BA. That is, there's some notion of which point is the first one. The second idea is unordered points, where AB and BA would be considered the same thing, where all that really matters is what the points are, and there's no meaning to which one is first.

Ultimately, we want to understand unordered pairs of points, but to get there, we need to take a path of thought through ordered pairs. We'll start out by straightening out the loop, cutting it at some point, and deforming it into an interval. For the sake of having some labels, let's say that this is the interval on the number line from 0 to 1.

By following where each point ends up, every point on the loop corresponds with a unique number on this interval, except for the point where the cut happened, which corresponds simultaneously to both endpoints of the interval, meaning the numbers 0 and 1. Now, the benefit of straightening out this loop like this is that we can start thinking about pairs of points the same way we think about pairs of numbers. Make a y-axis using a second interval, then associate each pair of values on the interval with a single point in this 1x1 square that they span out.

Every individual point of this square naturally corresponds to a pair of points on the loop, since its x and y coordinates are each numbers between 0 and 1, which are in turn associated to some unique point on the loop. Remember, we're trying to find a surface that naturally represents the set of all pairs of points on the loop, and this square is the first step to doing that. The problem is that there's some ambiguity when it comes to the edges of the square.

Remember, the endpoints 0 and 1 on the interval really correspond to the same point of the loop, as if to say that those endpoints need to be glued together if we're going to faithfully map back to the loop. So all of the points on the left edge of the square, like 0, 0, 0. 1, 0, 0.

2, on and on and on, really represent the same pair of points on the loop as the corresponding coordinates on the right edge of the square, 1, 0. 1, 1, 0. 2, on and on and on.

So for this square to represent the pairs of points on the loop in a unique way, we need to glue this left edge to the right edge. I'll mark each edge with some arrows to remember how the edges need to be lined up. Likewise, the bottom edge needs to be glued to the top edge, since y-coordinates of 0 and 1 really represent the same second point in a given pair of points on the loop.

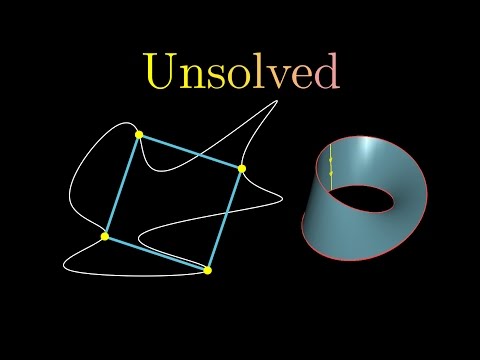

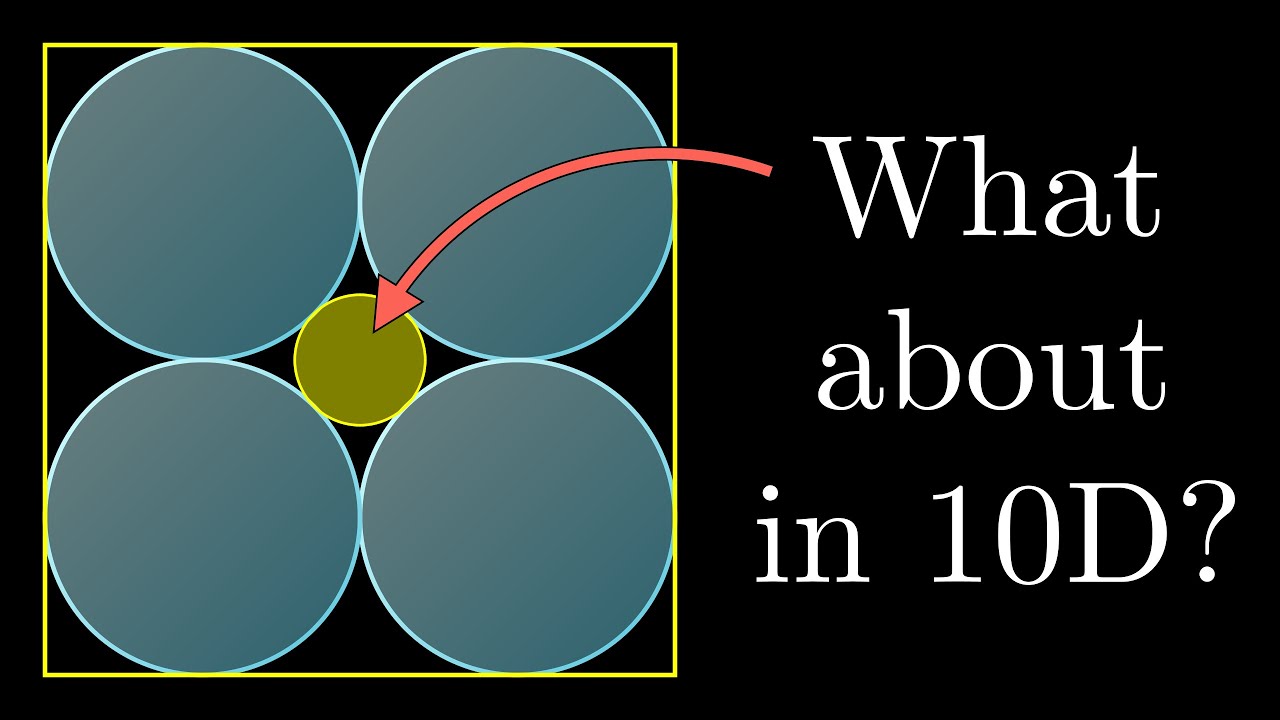

If you bend this square to perform the gluing, first rolling it into a cylinder to glue the left and right edges, then gluing the ends of that cylinder, which represent the top and bottom edges, we get a torus, better known as the surface of a doughnut. Every individual point on this torus corresponds to a unique pair of points on the loop, and likewise, every pair of points on the loop corresponds to some unique point on this torus. The torus is to pair of points on the loop what the xy-plane is to pairs of points on the real number line.

The key property of this association is that it's continuous both ways, meaning if you nudge any point on the torus by just a tiny amount, it corresponds to only a very slight nudge to the pair of points on the loop, and vice versa. So if the torus is the natural shape for ordered pairs of points on the loop, what's the natural shape for unordered pairs? After all, the whole reason we're doing this is to show that two distinct pairs of pairs of points on the loop share a midpoint and are the same distance apart.

But if we consider a pair AB to be distinct from BA, then that would trivially give us two separate pairs which have the same midpoint and distance apart. That's like saying you can always find a rectangle so long as you consider any pair of points to be a rectangle. Not helpful.

So let's think about this. Let's think about how to represent unordered pairs of points looking back at our unit square. We need to say that the coordinates 0.

2, 0. 3 represent the same pair as 0. 3, 0.

2. Or that 0. 5, 0.

7 really represents the same thing as 0. 7, 0. 5.

And in general, any coordinates x, y has to represent the same thing as y, x. Once again, we capture this idea by gluing points together when they're supposed to represent the same pair, which in this case requires folding the square over diagonally. Now notice this diagonal line, the crease of the fold.

It represents all pairs of points that look like xx, meaning the pairs which are really just a single point written twice. Right now, it's marked with a red line. And you should remember it.

It will become important to know where all of these pairs like xx live. But we still have some arrows to glue together here. We need to glue that bottom edge to the right edge.

And the orientation with which we do this is going to be important. Points towards the left of the bottom edge have to be glued to points towards the bottom of the right edge. And points towards the right of the bottom edge have to be glued to points towards the top of the right edge.

It's weird to think about, right? Go ahead, pause and ponder this for a moment. The trick, which is kind of clever, is to make a diagonal cut, which we need to remember to glue back in just a moment.

After that, we can glue the bottom and the right like so. But notice the orientation of the arrows here. To glue back what we just cut, we don't simply connect the edges of this rectangle to get a cylinder.

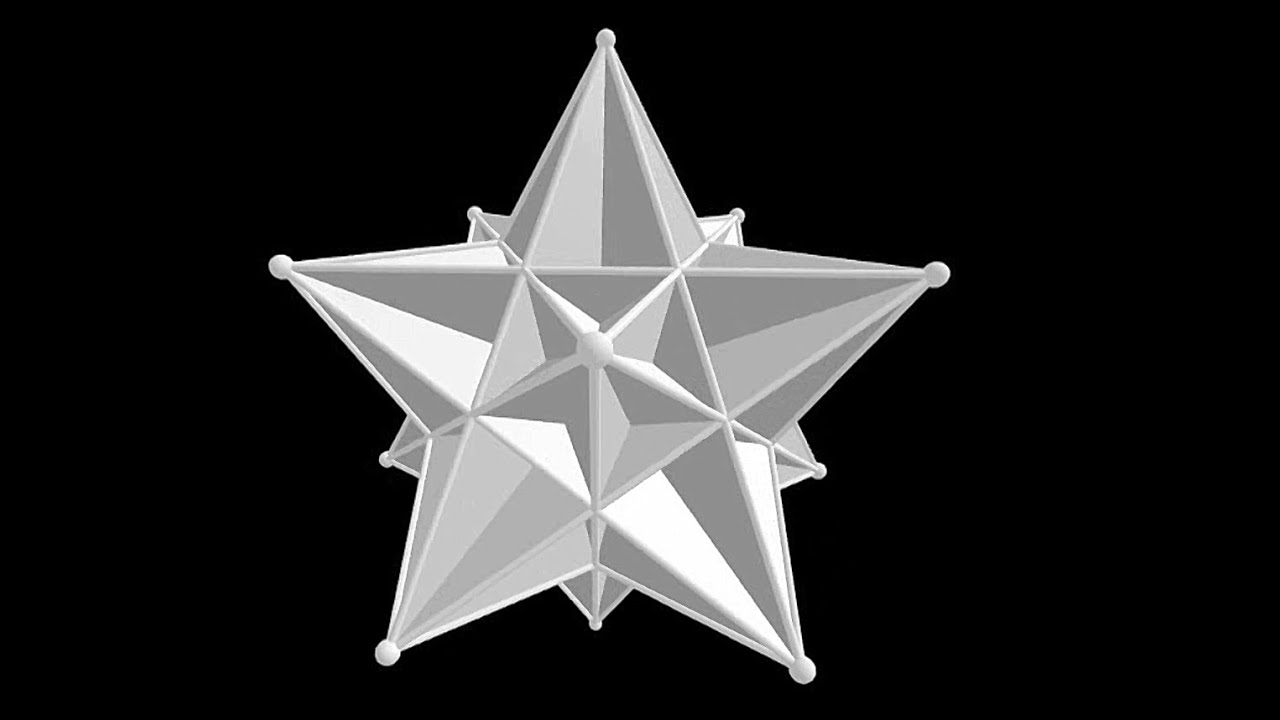

We have to make a twist. Doing this in 3D space, the shape we get is a Möbius strip. Isn't that awesome?

Evidently, the surface which represents all pairs of unordered points on the loop is the Möbius strip. And notice, the edge of this strip, shown here in red, represents the pairs of points that look like xx, those which are really just a single point listed twice. The Möbius strip is to unordered pairs of points on the loop what the xy-plane is to pairs of real numbers.

That totally blew my mind when I first saw it. Now, with this fact that there is a continuous one-to-one association between unordered pairs of points on the loop and individual points on this Möbius strip, we can solve the inscribed rectangle problem. Remember, we had defined this special kind of graph in 3D space, where the loop was sitting in the xy-plane.

For each pair of points, you consider their midpoint m, which lives on the xy-plane, and their distance d apart, and you plot a point which is exactly d units above m. Because of the continuous one-to-one association between pairs of points on the loop and the Möbius strip, this gives us a natural map from the Möbius strip onto this surface in 3D space. For every point on the Möbius strip, consider the pair of points on the loop that it represents, then plug that pair of points into the special function.

And here's the key point. When pairs of points on the loop are extremely close together, the output of the function is right above the loop itself, and in the extreme case of pairs of points like xx, the output of the function is exactly on the loop. Since points on this red edge of the Möbius strip correspond to pairs like xx, when the Möbius strip is mapped onto this surface, it must be done in such a way that the edge of the strip gets mapped right onto that loop in the xy-plane.

But if you stand back and think about it for a moment, considering the strange shape of the Möbius strip, there is no way to glue its edge to something two-dimensional without forcing the strip to intersect itself. Since points of the Möbius strip represent pairs of points on the loop, if the strip intersects itself during this mapping, it means that there are at least two distinct pairs of points that correspond to the same output on this surface, which means they share a midpoint and are the same distance apart, which in turn means that they form a rectangle. And that's the proof!

Or at least, if you're willing to trust me in saying that you can't glue the edge of the Möbius strip to a plane without forcing it to intersect itself, then that's the proof. This fact is intuitively clear looking at the Möbius strip, but in order to make it rigorous, you basically need to start developing the field of topology. In fact, for any of you who have a topology class in your future, going through the exercise of trying to justify this is a good way to gain an appreciation for why topologists choose to make certain definitions.

And I want you to take note of something here. The reason for talking about the torus and the Möbius strip was not because we were playing around with construction paper, or because we were daydreaming about deforming a coffee mug. They came up as a natural way to understand pairs of points on a loop, and that's something that we needed to solve a concrete problem.

Thank you.