The Strange Tale of Balaam and His Talking Donkey

14.42k views3455 WordsCopy TextShare

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

Episode 8: The Strange Tale of Balaam and His Talking Donkey

The seer Balaam from the book of Numbe...

Video Transcript:

Balaam the seer is a strange character in the Bible. A prophet of God, but not an Israelite. A paragon of righteousness and piety in some passages, a wicked idolater in others.

In the New Testament and writings of early Christians, he is regarded as both a herald of the messiah and a heretic consumed by greed. Oh, and he has a donkey that can speak. Who is Balaam, and how did his story end up this way?

Stick around, as we trace the history of one of ancient Canaan’s most famous legends—both inside and outside the Bible. In 1967, a large number of plaster fragments inscribed with lettering were discovered among rubble that was being removed from an archaeological site in Deir ‘Alla, Jordan—a region known as Gilead in the Bible. As archaeologists began piecing together the inscription, they found it was an oracle attributed to “the Book of Balaam, son of Beor, a seer of the gods.

” It was an exceptional find, for it is rare to see Bible characters mentioned in other ancient texts. Written around the year 800 BCE in a Canaanite dialect, the inscription tells of a vision granted to Balaam one night. In that vision, Balaam observes the divine council of El, the high god of the Canaanites and Israelites.

The council includes a group of gods called the Shaddayin, who call upon a goddess—most likely the sun goddess Shamash—either to cause or to relent from causing a catastrophe that involves darkness and a great flood. The poor condition of the fragments make it impossible to translate some portions with certainty, but the vision and Balaam’s reaction as he weeps and tells the people what is coming have striking similarities with many of the Bible’s prophecies of doom and judgment. The reference to the Shaddayin is also fascinating, because the singular form ‘Shaddai’ functions as an archaic and obscure name for God in the Old Testament.

In Exodus 6, Yahweh tells Moses that El Shaddai is the name by which he was known to earlier generations. In Balaam’s oracles in Numbers, he also calls himself “the one who sees the vision of Shaddai. ” The plural form can also be found in Deuteronomy 32:17 and Job 19:29, depending how those two verses are interpreted.

We may never know for sure if Balaam was a real person, but this find tells us that he was a well-respected character in the Iron Age Levant, and that the religious beliefs of his followers had much in common with the beliefs that shaped the Pentateuch. In the Bible, Balaam is introduced in the book of Numbers during the Israelites’ journey through the Transjordan on their way to the Promised Land. A shorter version of the same journey is told in the early chapters of Deuteronomy.

In those chapters, the Israelites pass through the lands of Edom, Moab, and Ammon peacefully and end up at a mountain called Pisgah, near the Jordan River and a place called Beth-Peor. This is the last stop of their journey before they cross the river and occupy the Promised Land. In Numbers, however, the story goes a bit differently.

A dispute with the king of Edom requires the Israelites to take a different route, and the Israelites end up camped in the plain near the Jordan River across from Jericho. The king of Moab, whose name is Balak, fears that the Israelites will attack him, so he concocts a plan to hire the famous prophet Balaam to place a curse on Israel. He dispatches his messengers to Balaam, who lives near a river “in the land of Ammo.

” It’s not clear exactly where this is, but the Jabbok River near Deir ‘Alla is one possibility. Balak’s envoys relay his message: Come now, curse this people for me, since they are stronger than I; perhaps I shall be able to defeat them and drive them from the land, for I know that whomever you bless is blessed, and whomever you curse is cursed. Balaam promises to give an answer by morning: Stay here tonight, and I will bring back word to you, just as Yahweh speaks to me.

That night, while Balaam sleeps, God comes to him in a vision, telling him to refuse Balak’s request. You shall not go with them; you shall not curse the people, for they are blessed. Upon waking, Balaam relays God’s message and sends the Moabites away.

Balak persists and sends a second delegation. This time, Balaam is told by God to go with them: Get up and go with them, but do only what I tell you to do. In the morning, Balaam saddles up his donkey and sets out with the Moabite officials.

However, the journey to Moab is interrupted by a strange episode in which an angel visible only to Balaam’s she-donkey blocks the way. When Balaam hits the donkey, she speaks in a human voice to protest. We’ll dig into this episode more later on.

Balaam then arrives at the River Arnon, the northern boundary of Moab, and meets with Balak. Balak takes him to a spot where the Israelites can be seen, but after building altars and performing sacrifices, Balaam pronounces an oracle of blessing over Israel instead of a curse. Two more times, an increasingly irate Balak takes Balaam to mountains overlooking the Israelites, and Balaam speaks blessings over Israel.

Balak gives up and tells Balaam he will receive no reward for his services. Balaam responds by giving one more oracle, this time predicting the defeat of Moab and other nations by a future Israelite king. The story concludes with Balaam and Balak going their separate ways and returning home.

Here, in the oldest biblical story about Balaam, the seer is viewed “unequivocally positively,” as Old Testament expert Jonathan Robker puts it. (p. 5) There are a few oddities with this passage that will be relevant later.

One is that the story twice mentions the “elders of Midian. ” Moab was in great dread of the people [of Israel], because they were so numerous…. And Moab said to the elders of Midian, “This horde will now lick up all that is around us, as an ox licks up the grass of the field.

” So the elders of Moab and the elders of Midian departed with divination in their hand…. This makes little sense, since Midian is located far to the south, beyond Moab and Edom, and has no connection with Moab or the events of this story. These elders of Midian have no function in the narrative and disappear after the story’s introduction.

They seem to be a late addition to the text, for reasons we shall see shortly. Another thing to note is that in chapter 25, immediately after the Balaam tale concludes, we have a strange and disturbing story—unrelated to Balaam—in which the women of Moab seduce the Israelites at Shittim and convince them to worship Moabite gods—particularly one called “Baal of Peor”. The Israelites are then struck with a plague that is only lifted when Phineas, grandson of Aaron the priest, brutally slays an Israelite man and his Midianite wife.

It’s not clear what this Midianite woman has to do with the Moabites or Baal of Peor, but the mention of the “summit of Peor” in Numbers 23:28 and Balaam’s patronym “Beor” might have suggested a link to the Baal-of-Peor incident. In other words, the editor of Numbers used word association and geography in his decision to recount the Balaam story before the unrelated Baal-of-Peor story. Several chapters later, in Numbers 31, we have a new story in which twelve thousand Israelites march off to war against Midian on the orders of Yahweh.

The Israelites slaughter the Midianites and plunder all their animals and possessions. Verse eight tells us that they also kill Balaam son of Beor “with the sword”. A few verses later, we are told that even the Midianite women must be killed because they had, on Balaam’s advice, incited the Israelites to betray Yahweh at Peor, thereby causing a plague.

This is quite a surprise, for as we just read in chapters 22–24, Balaam did no such thing. He never went to Midian, nor did he advise any women to lead the Israelites into idolatry. We were explicitly told that Balaam had simply returned to his home—which lay in the opposite direction from Midian—after blessing Israel four times.

Furthermore, the original Baal-Peor episode, which immediately followed the Balaam story, was primarily about Moabite women rather than Midianites. However, because the Baal-Peor incident and the Midianite wife incident directly followed the Balaam story in the narrative, the author of Numbers 31 has seen fit to combine them. He reshuffles their constituent elements and gives us a new story about Balaam, idolatry, and the Midianites — a group the author is strongly opposed to, for some reason — as antagonists.

The references to the “elders of Midian” were probably added to Numbers 22 at this stage to create a stronger association between Balaam and Midian, even though it makes no geographical sense. Robker notes: “Through no fault of his own, the character Balaam became affiliated with negative circumstances in the text of Numbers over the course of its redaction history. Numbers 31 took the Balaam legend in a new direction.

Balaam’s earlier righteous deeds were eclipsed by his new status as a villain and enemy of Israel. Later Old Testament authors persisted in depicting Balaam negatively, but doing so required harmonizing their accusations with the positive image of Balaam found in the original story. For example, Deuteronomy 23:3–5 cites the Balaam incident as an excuse to ban Moabites and Ammonites from the temple.

[The Ammonites and Moabites] hired against you Balaam son of Beor … to curse you. Yet Yahweh your God refused to heed Balaam; Yahweh your God turned the curse into a blessing for you, because Yahweh your God loved you. In this passage, possibly from the Persian era, the author shifts the blame away from the Midianites and toward the Moabites and the Ammonites—even though the latter had no role in the earlier Balaam stories.

To defend his negative depiction of Balaam, he states that Balaam actually did curse Israel, but Yahweh turned the curse into a blessing. Another example of this approach is found in Joshua 24:9–10, which is part of a longer summary of the exodus and wilderness journey. Then Balak son of Zippor of Moab arose and fought with Israel.

He sent and summoned Balaam son of Beor to curse them. But I was not willing to heed Balaam. He did in fact bless you, and I delivered you from his hand.

One problem with this summary is that Balak never actually fought Israel. Furthermore, the statement that Yahweh was not willing to heed Balaam contradicts the very next statement that Balaam actually blessed Israel. And whose hand did God deliver Israel from?

The syntax implies Balaam, but Balak must surely be meant. This is, in fact, a late change to the book of Joshua meant to vilify Balaam by implying he tried to curse Israel. The Greek Septuagint appears to preserve an earlier version of Joshua that agrees better with the original Balaam story: And Balak…rose up and set himself against Israel, and he sent for Balaam to curse you.

And the Lord your God was not willing to destroy you, and he blessed us with a blessing and rescued us out of their hands and gave them over. Let’s return to the talking she-donkey for a moment. Back in Numbers 22, while Balaam is traveling to meet King Balak, the angel of Yahweh is waiting for him on the road, armed with a drawn sword.

The jenny sees the angel and tries turning aside three times, and each time Balaam gets angry and strikes her to make her stay on the path. After her third beating, the jenny is suddenly endowed with speech by Yahweh, and instead of pointing out the angel, she “appeals to Balaam’s gratitude for her long service to him”. Finally, Balaam’s eyes are opened so he can see the angel and speak to it.

Balaam admits his fault, and the angel gives Balaam the same instructions that God had already given him back at home. The tale of the talking ass is widely understood as a secondary story inserted after Balaam had already been vilified. Robker calls it a “satirical fable.

” Yahweh’s anger at Balaam in this episode contradicts the fact that Balaam was commanded by God to go with Balak’s men just a few verses earlier. Animals that speak are rare in the Bible, the only other example being the loquacious snake in the Garden of Eden. The closest ancient literary parallel, in fact, is found in Homer’s Iliad, book 19.

As Achilles is chiding his horses for failing to protect his friend Patroclus in battle, the goddess Hera endows one of his horses, named Xanthus, with the ability to speak. Xanthus defends the two horses against Achilles’s accusation and promises to protect Achilles. The similarities with Balaam are striking: a heroic character treats his animal unjustly, whereupon a god or goddess opens the animals mouth so it can speak and defend itself by describing its loyal servitude.

A second Homeric parallel can be found in the Odyssey, book 16, in which the goddess Athena appears visible to some dogs but is invisible to Telemachus. We can’t be certain that the author of the donkey episode was familiar with Homer, but if he was, that would imply a late date of writing, during the Hellenistic era. There is in fact, more evidence for a late dating.

Balaam’s fourth oracle in Numbers 24 describes ships from Kittim attacking and subduing Mesopotamia after the Assyrian exile. While “Kittim” originally referred to Cyprus, it was later applied to the Greeks and Romans. Accordingly, this verse is thought by many interpreters to refer to the Greek conquest by Alexander the Great, as it does in 1 Maccabees.

From Villain to Messianic Prophet Up to this point, the Balaam narrative has been utilized to explain and defend the bad blood between Israel and its closest neighbors. To understand the next stage in the Balaam legend, we need to look at the content of his oracles—particularly this portion of Balaam’s fourth oracle: I see him, but not now;

I behold him, but not near.

a star shall come out of Jacob,

and a scepter shall rise out of Israel;

it shall crush the foreheads of Moab,

and the heads of the sons of Sheth.

In context, this is meant as a prophecy of King David—a prophecy already fulfilled, from the original reader’s perspective. But with the rise of Apocalyptic Judaism, it was reinterpreted as a prophecy of the end times—of the eschaton. Some scholars see a messianic view reflected in the various translations of this passage: the Septuagint replaces ‘scepter’ with ‘man’, and the Syriac Peshitta and some Aramaic Targums replace ‘star’ with ‘king’.

Furthermore, the Septuagint substantially rewrites verse 7, replacing Amalekite king Agag with the eschatological foe Gog from Ezekiel: A man will come forth from his offspring, and he shall rule over many nations, and his reign shall be exalted beyond Gog, and his reign shall be increased. During the inter-testamental period, the Jewish sect at Qumran held this oracle of Balaam's in uniquely high regard. According to the famous Damascus Document, they believed in two immanent messiahs: a military leader called the Prince of the Congregation, who was represented by the scepter, and a great priest called the Interpreter of the Law, who was represented by the star.

Curiously, they did not mention Balaam by name when citing the prophecy; perhaps due to his sullied reputation, they wanted to avoid connecting him with their prophecies. As Robker puts it, “They liked the message, but hated the messenger. ” Balaam’s fourth oracle is also cited in a messianic context in at least three other Dead Sea Scrolls: the War Scroll, 4QTestimonia, and 4Q541.

Many of these ideas about the Jewish Messiah as a savior figure associated with a star found a new home in Christianity. It is widely believed that Matthew had Balaam’s oracle in mind when he wrote his nativity story about a star appearing at Christ’s birth. And it is perhaps no accident that Jesus’ birth was attended by Magi who knew how to interpret the star, since Balaam was associated with the magi by early Christians as well as some Jewish writers, notably Philo of Alexandria.

Perhaps it is also not coincidence that Jesus’s grandfather is named Jacob in Matthew. In Matthew, as in the Dead Sea Scrolls, the author was reticent to mention Balaam because of his villainous reputation. This tension is evident in other Christian writings, and some authors would even misattribute Balaam’s oracle to a more suitable prophet, such as Isaiah.

Justin Martyr provides an early example of this: Another prophet, Isaiah … spoke thus: ‘A star shall rise out of Jacob, and a flower shall spring from the root of Jesse, and in His arm shall nations trust’. Indeed, a brilliant star has arisen, and a flower has sprung up from the root of Jesse—this is Christ. Christian writers continued to embellish the villainy of Balaam in New Testament times.

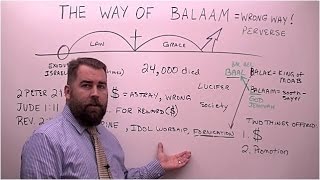

Jude 11 describes false teachers as those who “abandon themselves to Balaam’s error for the sake of wages”—implying that Balaam had been motivated by greed to commit wrongful acts, which is consistent with Rabbinic exegesis but not with the story in Numbers. Second Peter, a book closely related to Jude, also compares false teachers to Balaam. Like Jude, he highlights Balaam’s supposed greed, but he also can’t help mentioning the donkey.

They have left the straight road and have gone astray, following the road of Balaam son of Bosor, who loved the wages of doing wrong, but was rebuked for his own transgression; a speechless donkey spoke with a human voice and restrained the prophet’s madness. By the way, the mistaken patronym “Bosor” is strange. Robker theorizes that the author was summarizing the Balaam story from memory.

Lastly, the author of Revelation condemns the doctrine of his opponents as “the teaching of Balaam, who taught Balak to put a stumbling block before the people of Israel, so that they would eat food sacrificed to idols and practice fornication. ” (Rev. 2:14) This idea that Balaam gave Balak instructions for leading the Israelites astray comes from a Jewish tradition also found in Josephus, Antiquities 4.

129. What do we make of the Balaam character in light of his strange journey through time and tradition? It seems to me that Balaam’s status as both a famous seer and an outsider made him the ideal scapegoat for the strife and divisions that emerged over the course of Judaism and early Christianity.

Remember that early story in Deuteronomy of Israel’s trek out of Sinai? It describes how the Israelites were able to peacefully pass through the lands of Edom, Moab, and Ammon before crossing the Jordan. Yahweh even emphasized that he had given each of those nations—siblings of Israel—their respective lands.

Then Yahweh said to me: …You are about to pass through the territory of your kindred, the descendants of Esau, who live in Seir. … So we passed by our kin, the descendants of Esau who live in Seir, leaving behind the route of the Arabah and leaving behind Elath and Ezion-geber. But in Numbers, the events unfold differently.

The king of Edom refuses to grant passage through his country, so Israel is forced to go the long way around. Edom said to him: You shall not pass through, or we will come out with the sword against you. … Thus Edom refused to give Israel passage through their territory, so Israel turned away from them.

Here, Moab is also depicted as an enemy of Israel, and king Balak hires Balaam to curse Israel. Balaam is innocent in the narrative, but from this point on, he is inextricably associated with Israel’s enemies. Just a few chapters later, we have a war with Midian, for which Balaam is blamed.

And in Deuteronomy 23, both Moab and Ammon are condemned for hiring Balaam to curse Israel. Centuries later, as the nascent Christian community became embroiled in theological disputes, its leaders would once again invoke the name of Balaam to accuse their opponents of encouraging idolatry and being motivated by greed. And so, the legend of a great seer of international fame who could commune with the gods themselves ends in humiliation, as Balaam becomes a tool for political agendas, a lightning rod for strife and squabbles, and a laughingstock who was rebuked by his own donkey.

Related Videos

42:45

Balaam's Talking Donkey - Brad Gray

Walking The Text

24,373 views

12:15

Balaam and his donkey | Animated Bible Sto...

My First Bible

159,520 views

28:42

I actually read the Baal myth...here's wha...

DiscipleDojo

400,392 views

30:38

Who was Balaam And Why Is He Important To ...

Grace Digital Network

488,831 views

28:30

Rick Renner —Who is Balaam?

Renner Ministries

36,030 views

28:06

Lessons from the story of Balaam and his t...

Broadway Church

6,844 views

46:51

Balaam: The Madness of the Prophet – Numbe...

David Guzik

7,124 views

18:30

King Saul and the Ghost of Samuel – Death ...

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

6,604 views

26:57

The Riddle of the Golden Calf – A Story Sh...

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

9,193 views

43:11

Who is Yahweh - How a Warrior-Storm God be...

ESOTERICA

2,477,428 views

34:04

Joseph: The History of a Jewish Novella

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

4,601 views

12:55

Lost in Translation: Genesis 1 is NOT Abou...

James Tabor

333,231 views

39:28

The ORIGIN of Nimrod Will BLOW Your Mind! ...

MythVision Podcast

240,565 views

14:02

The First Nicene Council of AD 325: Unitin...

Theology Academy

49,529 views

21:51

The Philistines in History and the Bible

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

18,674 views

24:43

Leviathan and Yahweh's Conquest over the Sea

The Inquisitive Bible Reader

32,395 views

21:49

RABBINIC JUDAISM Led Me to JESUS | Eduard...

SO BE IT!

122,233 views

13:21

Dr. Ted Hildebrandt, Old Testament Literat...

Ted Hildebrandt Biblicalelearning

7,468 views

1:06:42

The Way of Balaam

Robert Breaker

50,025 views

11:35

Septuagint 📖 The Most Dangerous Book in t...

Digging up the Bible

402,951 views