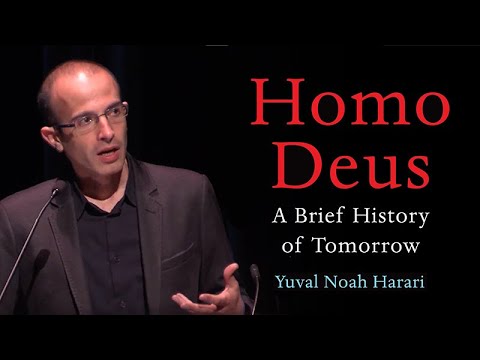

Homo Deus: A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOMORROW with Yuval Noah Harari

1.89M views7332 WordsCopy TextShare

University of California Television (UCTV)

Historian Yuval Noah Harari has taken the world on a tour through the span of humanity, from apes to...

Video Transcript:

(lighthearted guitar music) (audience clapping) - Thank you, it's a honor and a daunting privilege to introduce Professor Yuval Harari. Dr Harari is a lecturer at the Department of History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He received his PhD from the University of Oxford in 2002.

He is a best-selling author, he was the author of "Sapiens: A Brief History "of Humankind", that was number one in The New York Times Best Seller and just recently, appearing "Homo Deus: A Brief History "of Tomorrow". He's won numerous awards including twice the Polonsky Prize for creativity and originality in 2009, and 2012 and numerous other books and really notable honors. Oftentimes, when we think about historians, we imagine them focusing on some very narrow topic, some particular era, some 20 years, some particular author, some particular battle, something of that sort.

My apologies to historians in the audience who I may have insulted, (audience laughing) but this is sort of our stereotype. But Professor Harari is exactly the opposite of that sort of narrow perspective. He has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to ask really, really big questions and to contextualize them in a truly daunting manner.

He asks questions such as, how do we get from being an insignificant species, that he compares to being no more impactful than jellyfish or woodpeckers to as recently as 70,000 years ago, to dominating the globe the way no species has ever done? What are the stages that humanity has gone through? And how can we understand those stages?

Are we happier today than we were in the past? And remarkably and curiously he concludes, perhaps not. And one of the most challenging of all questions is what makes humans special?

What distinguishes humans from the rest of the species that are out there? And his answer, for at least the first part of it, is relatively straightforward. He argues that humans are able to evidence flexible cooperation in large numbers.

Yes, other animals can cooperate, chimpanzees can cooperate, but not in large scales though, groups of maybe 15, 20, 30, but certainly not in the hundreds thousands that humans are. Bees can operate in large scale, but not flexibly. What distinguishes humans is their capacity to be both able to operate in these large scales and to operate cooperatively and flexibly.

And then he asks the question, the harder question, how do we do it? How are we capable of manifesting this remarkable flexibility at such a large scale? And here his answer is really very timely, especially in this time of fake news and alternative facts, things that we are the sort of, how can people believe these things?

How can this be possible? And his conclusion is that, in fact, our capacity to believe in such things is actually part of what makes us so special. That ultimately, it's humankind's imagination and our ability to believe in fictions, to hold collectively a belief in fictions, which is what gives us our remarkable capacity.

So, our fake news and our alternative facts and our willingness to believe in this, although these may have some serious consequences, may also be reflective of what has gotten us here in the first place. So he argues that there're really also these two aspects of reality. There's objective reality that we share with animals, and then there's the fictional reality, which is what makes us unique and special.

And the things that he includes in fictional reality, is most of the things that we take nearest and dearest, things like religion, corporations, nations, rights, laws, countries, even money. All of these are fictions, but they are tremendously powerful fictions. They are what give us the glue that holds us together and allows us to operate in such a remarkable power.

So ultimately, according to DrHarari, the power of humanity is in its capacity to tell and believe in great stories. And I'm confident that Dr Harari will demonstrate this capacity to tell great stories this evening. With no further ado, Dr Harari.

(audience clapping) - Thank you. So thank you for this introduction, and thank you all for coming to hear me. And I want to speak today about not the past, not how we got here, but about the future, how we proceed from here.

And in fact, I don't think that Homo sapiens has much of a future left. We are probably one of the last generations of Homo sapiens, in a century or two at most, I guess that humans like you and me will disappear, and earth will be dominated by very different kind of beings or entities. Beings that will be more different from us than we are different from Neanderthals or from chimpanzees.

And we are beginning to see the signs of this revolution all around us. And I want to tonight to focus on one particularly important sign, which is what is happening to authority. To the shift, authority is now shifting away from humans.

For centuries, for thousands of years really, we have been accumulating power and authority in our own human hands, but now, authority is beginning to slip away, to shift from us to other entities, and in particular, to shift from us to algorithms. But before discussing these algorithms, and their potential for being the new rulers of the world, I want to spend a few minutes looking at the last few centuries, which saw really the apogee of human authority, in the shape of the ideology or worldview known as humanism. For centuries before, humans believed that the real source of authority in the world, is not their imagination, is not their collective power, but most humans thought that authority actually comes from outside, authority comes from above the clouds, from the heavens, authority comes from the gods.

The most important sources of authority in politics, in economics, in ethics, were the great gods, and their sacred books, and their representatives on Earth. The priests, the rabbis, the shamans, the caliph, the popes and so forth. Then in the last two, three centuries, we saw the humanist revolution, a tremendous political and religious and ethical revolution, which said basically, which brought down authority from the heavens down to earth, down to humans, and said that the most important source of authority, the supreme source of authority, in all fields of life is human beings, and in particular, it is the feelings and the free choices of human individuals.

What humanism told humans, is that when you have some problem in your life, whether it's a problem in your personal life, or whether it's a problem in the collective life of an entire society, or an entire nation, you don't need to look for the answer from God or from the Bible or some big brother. You need to look for the answer within yourself, in your feelings, in your free choices. And we've all heard thousands of times these slogans which tell us, listen to yourself, connect to yourself and follow your heart, do what feels good to you.

And these are really the most important ideas or advices about authority for the last two or three centuries. In almost all fields of life, if we start with politics, so in a humanist world, in a world that believes that the highest authority is human feelings, in politics this manifests itself in the idea that the voter is the supreme authority, the voter knows best. When you have some really big political decision, like who should rule the country, who should be president, so you don't ask God and you don't ask the pope, and you don't ask the Council of Nobel Laureates.

Rather you go to each and every Homo sapiens, and you ask, "What do you think? "What do you feel about this question? ".

And most of the time, it's really the feelings that decide the issue. It's not rational thinking, it's human feelings. And the common assumption in humanist politics is that there is no higher authority than human feelings.

You cannot come to humans and tell them, "Yes, you think like that, you feel like that. "But there is some higher authority "that tells you that you are wrong". This was the case, for example, in the Middle Ages, but not in modern humanistic politics, certainly not in a democracy.

The same thing is true also in the economic field. What is humanist economics? It's an economic view that says that the highest authority is the feelings, the wishes, the whims of individual customers.

The customer is always right. How do you know if an economic decision is the right decision? How do you know if a product is a good product?

In a humanist economy, you ask the customers, the customers vote with their credit card, and once they've voted, there is no higher authority that can tell the customers, "No, you are wrong". Let's say you want to produce the best car in the world, what is the best car in the world? So let's say Toyota or Ford want to produce the best car in the world.

They gather together the Nobel Prize winners in physics in chemistry in economics. They bring together the best psychologists and sociologists, they even throw in the best artists and the Oscar winners and whatever. And they give them four years to think together and design and manufacture the perfect car.

And they do it. And they produce the Toyota perfect or the Ford perfect. And then they produce millions of these cars, and send them to car agencies all over the country or all over the world.

And the customers don't buy the cars. What does it mean? Does it mean that the customers are wrong?

No, the customer is always right, in a humanistic economy. It means that all these wise people are wrong. They are not a higher authority than the customer.

In a communist dictatorship, you can come to the people and say, "This is "the car for you, "the Politburo decided in its wisdom, "that this is the perfect car for the Soviet worker "and this is the car you're going to have". But this is not how it works in a liberal humanistic economy, where there is no higher authority than the customer. The same idea is also found at the basis of modern art.

What is humanist art? It is art that believes that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. How do you know what is art?

How do you know what is good art? What is beautiful and what is ugly? For thousands of years, philosophers and thinkers and artists had all kinds of theories about what is art and what is beautiful.

And usually, they thought that there was some objective yardstick. A divine yardstick probably, that defines art and beauty. God defines what is art and what is beautiful.

Then came along humanist aesthetics in the last two centuries and shifted the source of authority to human feelings. Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. In 1917, exactly a century ago, Marcel Duchamp took an ordinary mass-produced urinal declared it a work of art, named it Fountain, and ever since then, if you went to a first year course in art history, you probably saw this image almost in every first year history of art course they bring this image in one of the first lessons, and the lecture shows the image and asks the students, "Well, what do you think?

". And all hell breaks loose. "Hey, it's art, it's not art, it is, it isn't".

How do you define art? And at least if this is a humanist university or humanist college, the lecture will steer the discussion to the conclusion that there is no objective definition or yardstick for art, or for beauty. Art is anything that human beings think or define as art, as beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

If you think that this is beautiful, this is a beautiful work of art, and you're willing to pay millions of dollars to have it in your home, and it costs millions of dollars. Now the Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, then who is there in the world that can tell you that you're wrong? And that you don't know what art is or what beauty is?

So this is humanist aesthetics. The same principle also appears in the ethical field. What is good and what is evil?

What is a pious action and what is a sin? So in previous eras, again, you went to God or you went to the pope, or you went to the Bible. Let's say, with the case of homosexuality.

So in the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church came and said homosexuality is a sin. Why? Because God said so, because the Bible said so, because the pope said so.

And this was the source of ethical authority. Nobody cared much what people actually felt about it. Now, in the era of humanist ethics, the saying is we don't care very much what God says, or what the Bible says or what the pope says.

We want to know how people actually feel. If two men are in love, and they both feel very happy with that, and they don't harm anybody, so what could possibly be wrong with it? It's very simple.

The highest authority in the field of ethics is the authority of human feelings. If humans feel good about something, and nobody feels bad about it, then it's good. Of course, there are some difficult questions also in humanist ethics.

What happens if I feel good about something, let's say an extramarital affair, but my husband feels very bad about it? So whose feelings count for more? Then you have a dilemma an ethical dilemma, you have a discussion.

But the key point is that the discussion will be conducted in terms of human feelings, not in terms of divine commandments. It's interesting that today, even some religious fundamentalists have learned this trick. And they're using the language of human feelings and not the language of divine commandments.

I come from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and every year for the past 10 years or so, we have in Jerusalem, our own gay parade, which is a very rare day of harmony in Jerusalem, because this is a very conflict-ridden city for most of the year, but the gay parade is a special day of harmony, because then you have all the Orthodox Jews and Muslims and Christians coming together to fume and to shout against the gay parade. (audience laughing) So we have one day of harmony in this city. (audience laughing) But the really interesting thing is the arguments that at least some of them use.

They go to the television or to the radio, and they say it hurts our feelings. They don't say God said that homosexuality is a terrible sin. Some of them say so of course, but when they go on television, they would usually say they shouldn't hold the Gay Pride Parade in Jerusalem, because it hurts our feelings.

Just the same way that gay people want us to respect their feelings, they should respect our feelings and hold the parade in Tel Aviv or some other place not in Jerusalem. (audience laughing) Now, again, it doesn't really matter what you think about the argument, the interesting point here is that even such religious fundamentalists have learned that it's more effective to conduct the debate in terms of human feelings, and not in terms of divine commandments. And finally, since we are in a university, so let's say a few words also about education.

So what is humanist education? For hundreds of years when people thought that the supreme source of authority was outside humans, the main aim of education was to connect people to that outside source of authority. If you thought, for example, that the Bible was the highest source of authority, or God was the highest source of authority, then the main purpose of education, was to teach you what God said, and what the Bible said, and what the wise people of the past have said.

In humanist education, since the highest source of authority is your own feelings and your own thoughts, the chief aim, the most important aim is to enable you to think for yourself. You go to everybody from kindergarten to the professor of that university, and you ask them, "What are you trying to teach the kids, "the pupils, the students? ".

And they will tell you, "Oh, we try to teach mathematics "and we try to teach physics, "and we try to teach history, "but above all, "I try to teach my students to think for themselves". This is the highest ideal of humanist education, because this is the source of authority, you have to be able to connect to it. Now, all of this is now under the cloud now facing a huge threat a deadly threat.

This entire humanist worldview is facing a threat, not so much from religious fundamentalists, or from dictators in North Korea or Russia or elsewhere. The really big threat to the humanist worldview is now emerging from the laboratories, from the universities, from the research departments in places like Silicon Valley, because what more and more scientists are telling us, is that this entire story of humanism is really based on outdated science or an outdated understanding of the world, and in particular, an outdated understanding of Homo sapiens, of this ape from East Africa. Humanism is based on a belief in free will, in the ability of humans to make free choices and a very strong belief in human feelings as the best source of authority in the world.

But, now scientists are saying, first of all, there is no such thing as free will. Science is familiar with just two kinds of processes in nature. You have deterministic processes, and you have random processes, and of course, you have combinations of randomness and determinism, which result in a probabilistic outcome, but none of that is freedom.

Freedom has absolutely no meaning from a physical or biological perspective. It's just another myth, another empty term that humans have invented. Humans have invented God, and humans have invented heaven and hell, and humans have invented free will, but there is no more truth to free will than there is to heaven and hell.

And as for feelings, they are definitely real, they are not a fiction of our imagination, but feelings are really just biochemical algorithms, and there is nothing metaphysical or supernatural about them. There is no obvious reason to consider them as the highest authority in the world, and most importantly, what scientists and engineers are telling us more and more, is that if we only have enough data, and enough computing power, we can create external algorithms that understand humans and their feelings much better than humans can understand themselves. And once you have an algorithm that understands you, and understands your feeling better than you understand yourself, this is the point when authority really shifts away from humans to algorithms.

Now, that sounds both frightening, I guess, and complicated. So I'll try to explain what it means. First of all, what does it mean, that feelings and organisms really are algorithms?

You can say that, in a way it's possible to summarize more than a century of research in the life sciences and especially in biology and in evolution, in just three words, organisms are algorithms. This is now more and more the dominant view, not only in the life sciences, but also in computer science, which is why the two are merging, and what this idea that organisms are algorithms, what it really means is that human feelings and not just human, also chimpanzee and elephant and dolphin feelings, sensations and emotions, they're all just a biochemical process of calculation, calculating probabilities in order to make decisions. Feelings are not some metaphysical quality that God gave Homo sapiens in order to write poetry and appreciate music, feelings are processes of calculation, biochemical calculation, shaped by millions of years of natural selection, to enable humans and other mammals and other animals to make good decisions when they are faced with problems of survival and reproduction.

What does it mean? Let's take a concrete example. Let's say you're a baboon somewhere in the African savanna, and you face a typical problem of survival.

In order to survive, you have to eat, in order to survive you have to be careful not to be eaten by somebody else. And let's say that as you walk along the savanna, you suddenly see a tree with bananas on it. But you also see a lion, not far from the tree.

And you need to make a decision whether to risk your life for the bananas or not. This is the kind of problem that animals like baboons and like humans have been facing for millions and millions of years. Now in order to.

. . This is really a question of calculating probabilities.

I the baboon, I need to calculate the probability that I would starve to death if I don't eat the bananas, versus the probability that the lion will eat me if I try to reach for these bananas. I need to know which probability is higher in order to make a good decision. For that, I first of all need to collect a lot of data, I need data about the bananas.

How far are the bananas? How many bananas? Are they big or small?

Ripe or green? It's one situation when we are talking about 10 big ripe bananas, and it's very different if you have just two small green bananas. Similarly, I need information, I need data about the lion.

How far is the lion? How big is the lion? How fast I think the lion can run.

Is the lion asleep or awaken? Does the lion look hungry or satiated? I need all these kinds of data about the lion.

And of course, I need a lot of data about myself, how hungry I am, how fast I can run and so forth. Then I need to take all these pieces of data and somehow calculate them very, very fast, the probabilities. How does the baboon do it?

The baboon does not take out a pen and a piece of paper or calculator and start calculating probabilities. No, the entire body of the baboon is the calculator. It takes in the data with what we call our senses, our sensations, with our sight, with our smell, with our ears, we take in all the data also from within the body, and then the nervous system and the brain, they're the calculator that within a split second, calculates the probabilities, and the answer will appear not as a number, the answer will appear as a feeling or an emotion.

If chances are that I should go and get the bananas, then this will appear as the emotion of courage. I will feel very courageous, I feel I can do it, or my hair will stand out, my chest will puff up, and I'll run for the bananas. If the result of the calculation is that it's too dangerous, then this too will appear not as a number, but as an emotion, this is fear.

This is how fear emerges. And I will be very frightened and run away from there. So what we, in day to day language call feelings and emotions and so forth, according to the standard theory today in the life sciences, these are really biochemical algorithms calculating probabilities.

Now until today, until the early 21st century, this idea, this understanding that organisms are algorithms, that emotions and feelings are really just a biochemical process of calculating probabilities, this didn't have much of a practical impact, because nobody had the capacity to collect enough data, and nobody had the computing power necessary to analyze that data, and really understand what's happening within me. For thousands of years, all kinds of authorities tried to hack humans, tried to understand what goes through our minds, what do we think? What do we feel?

But nobody was really able to do it. The Catholic Church in the Middle Ages or the KGB in Soviet Russia, they were very interested in understanding humans, in hacking humans, but they couldn't do it. Even if the KGB followed you around everywhere and recorded every conversation you had, and every activity that you took, the KGB did not have the biological understanding, and it did not have the computing power necessary to really make sense of what happens within the human brain or within the human body.

So until today, when humanism told people, don't listen to the pope, don't listen to the Bible, don't listen to Stalin, don't listen to the KGB, listen to your feelings. This was good advice. Because your feelings really were the best methods for making decision, they're the best algorithm in the world.

Your feelings, human feelings were algorithms shaped by millions of years of natural selection, algorithms that withstood the harshest quality tests in the world, the quality tests of natural selection. So if you had to choose between listening to the Bible, and listening to your feelings, it was very good advice, what humanism told you, listen to your feelings. The Bible was just the wisdom of a few priests in ancient Jerusalem.

Your feelings were the best mechanism for making decision that has been shaped by millions and millions of years of natural selection. So it made good advice to listen to your feelings. But now, things are changing.

We are now at the intersection or at the collision point between two immense scientific tidal waves. On the one hand for more than a century, at least since Charles Darwin, we have been gaining a better and better understanding of the human body, and of the human brain, and of human decision making and human emotions and sensations and so forth. And at the same time, with the rise and development of computer science, we have been learning how to engineer better and better electronic algorithms, with more and more computing power.

Until today, these two were kind of separate developments, but now they are coming together. I think the crucial thing that is happening right now in the second decade of the 21st century, is the merging of these two tidal waves. The wall separating biotech from infotech is collapsing, which you can also see in the market, that corporations like Apple or Amazon or Google or Facebook, that began as strictly infotech corporations, are increasingly becoming biotech.

Because really, there is no longer any essential difference between the two. And we're very close to the point when unlike the KGB, and unlike the Catholic Church, Facebook or Google will be able to understand you better than you understand yourself. Because they will have the data, they will have the biological knowledge, and they will have the computing power necessary to understand exactly how you feel, and why you feel the way that you feel.

This is already happening in one very important field which is the field of medicine. In the field of medicine, it's already happened basically. Authority has already began to shift dramatically from humans to algorithms.

I think it's a very fair estimate or prediction, that the most important decisions about your health, about your body, during your lifetime will not be taken by you on the basis of your feelings, they will be taken by algorithms on the basis of what they know about you and you don't know about yourself. To give a practical real life example, which made a lot of headlines. Two, three years ago, there was this very famous story about Angelina Jolie.

She did a genetic test, a DNA test that revealed she had a mutation, I think it was in the BRCA1 gene. And according to big data statistics, women who have this particular mutation in this particular gene, they have an 87% chance of getting breast cancer. Now, at the time, Angelina Jolie did not have breast cancer.

She of course made all the tests and checks and she did not have breast cancer at the time. She felt also perfectly healthy. Her feelings were telling her, "You're perfectly okay.

"You don't need to do anything". But the big data algorithms, they were telling her a very different story. They told her you have a time bomb ticking in your DNA.

And even though you don't feel anything is wrong, you had better do something about it now. And Angelina Jolie very courageously and sensibly preferred to listen to the algorithm, and not to her own feelings. She underwent a double mastectomy, and also published her story, I think it was in The New York Times in order to encourage other women to do similar tests and perhaps take similar preventive steps.

So this kind of scenario, that your feelings tell you you're absolutely okay, but some big data algorithm that knows you, tells you no, you're not okay, and you prefer to listen to the algorithm, this I think is more and more going to be the shape of medicine in the 21st century. But it won't remain restricted to medicine. We are likely to see a similar shift in authority in almost all fields of human activity.

In the past, say in the Middle Ages, you had the monotheistic and polytheistic religions, telling people authority comes down from the clouds, from the gods. If you have a problem in your life, listen to the Word of God, listen to the Bible. Then you had humanism, coming and telling people let's bring down authority from the clouds to human feelings.

Don't listen to the Bible, don't listen to God, to the pope, listen to your own feelings. Now, we are seeing the rise of a new worldview, or a new ideology, which we can call dataism, because it believes that authority in the end comes from data. And dataism shifts back authorities to the clouds, to the Google Cloud, (audience laughing) to the Microsoft Cloud.

And dataism tells people, "Don't listen to your feelings, "listen to Google, listen to Amazon. "They know how you feel, "and they also know why you feel the way that you feel, "and therefore they can make better decisions "on your behalf". What does it mean in practice?

It's very important for me as a historian, to always bring down not only authority from the clouds to humans, but also bring down these very abstract ideas to concrete examples from the daily life of people. So what does it mean, that authority shifts away from our feelings to these external algorithms? So because I write books, I'm very interested in books.

So let's take an example from the world of books. A mundane decision that you need to take what book to read? So in the Middle Ages, you went to the source of authority, to the priest, and you asked the priest what book should I read?

And the priest will tell you read the Bible, it's the best book in the world, all the answers are there, you don't need to read any other book in your life, just the Bible is enough. Then came humanism in the last two, three centuries, and told people, "Ah, yes, the Bible, "there are some nice chapters there, "but so many parts of it, "they really need a good editor. (audience laughing) "And really, you don't need to listen to anybody, "other than yourself, "just follow your feelings".

There are so many good books out there in the world. You go to a bookshop, you wander between the aisles, you take this book and that book, you flip through, you feel some gut instinct, connecting you to a particular book, take this book, buy it, read it. So this was the humanist way of choosing which book to buy.

Now with the beginning of the rise of dataism, we go to the Amazon virtual bookshop, and the moment I enter the Amazon Bookshop, an algorithm pops up and tells me, "I know you. "I've been following you, "I've been following your likes and dislikes, "and based on what I know about you, "and statistics about millions of other readers and books, "I recommend these three books to you". But this is really just the first small baby step.

The next step, which is already being taken today, is that Amazon in order to improve the algorithm, it needs more and more data on you, and your preferences and your feelings. So if you read, like me, if you read a book on Kindle, you should know that as you read the book, for the first time in history, the book is reading you. It never happened before.

You go back to ancient times or you go back to the early modern print revolution, so Gutenberg brought print to Europe and they started printing books, but all these books printed by Gutenberg and his successors, they never read people. It's only the people who read the books. Now books are reading people.

As I or you read a book on Kindle, Kindle is following me. Kindle knows which pages I read fast, which pages I read slow, it's very easy for Kindle to know that. And Kindle also notices when I stop reading the book, and perhaps never coming back to it.

Based on that kind of information, Amazon has a much better idea what I like and what I don't like. But this is still very, very primitive. The crucial thing is to get to the biometric data, to get within your body, to get within your brain in your mind.

And this can start to happen today. If you connect Kindle to face recognition software, which is already in existence, then Kindle could know, when I laugh, when I cry, when I'm bored, when I'm angry, based on my facial expression. It's the same way that I know what's your mood now, what your emotion is by trying to read your faces.

We can now have Kindle reading the faces of readers. And based on that, Amazon will have a much better idea of what I like or don't like. But this is still primitive, because it still doesn't really get inside the body.

The really crucial step, and we are very, very close to that step, is when you connect Kindle to biometric sensors on or inside my body. And once you do that, Kindle will know the exact emotional impact of every sentence I read in the book. I read a sentence, and Kindle knows, which means Amazon knows, what happened to my blood pressure, what happened to my adrenaline level, what happened to my brain activity as I read this sentence.

By the time I finish the book, let's say I read Tolstoy's "War and Peace". By the time that I finish reading Tolstoy's "War and Peace", I forgot most of it. (audience laughing) But Amazon will never forget anything.

By the time I finish "War and Peace", Amazon knows exactly who I am, what is my personality type, and how to press my emotional buttons. And based on this Kind of knowledge, it can do far more than just recommend books for me. In different situations, it could be taken in different ways.

If you live, let's say in North Korea, so everybody will have to wear this biometric bracelet, and if you enter a room and you see a picture of Kim Jong-un, and your blood pressure and brain activity indicates anger, then that's the end of you. (audience laughing) In a liberal society, like the United States, it can go in different directions. Amazon recommending not just things like books, but far more important things like dates or even marriages.

Like let's say that I'm in a relationship, and my boyfriend asks me, well, I want to get married, either we get married or we separate, you have a choice. So kind of one of the most important choices that any animal needs to make during its lifetime about mates. So let's say you're presented with this dilemma, either we get married, or we're separating, no third option.

So, in the Middle Ages, you would go to the priest to ask for advice. In the humanist age, in the 19th and 20th century, they will tell you just follow your heart. Just try to connect to your authentic self and just follow your heart.

In the 21st century, the advice will be "Oh, listen to Amazon, "ask Google what to do". And I would come to Google or Amazon, and I would say, "Google, I have this dilemma. "What do you recommend that I do?

"What is the best course of action for me? ". And Google will say, "Oh, I've been following you around "during your lifetime.

"I've been reading all your emails "and all your search words on the internet. "I've been listening to all your phone calls, "I've been tracking whenever you saw movie or read a book, "I saw what was happening to your heart. "Also, every time you went on a date, "I followed you around "and I saw what happened to your blood pressure, "or to your heart rate or to your brain activity.

"And I know your DNA scan "and all your medical records and then whatever. "And of course, I know I have all this data, "also about your boyfriend or your girlfriend, "and I have data on millions and millions of successful "and unsuccessful relationships. "And based on all this data, "I recommend to you with a probability of 87%, (audience laughing) "that it's a good idea to get married.

"That's the best thing for you, to get married". But Google will tell me, "I know you so well, "that I even know you don't like the advice I now gave you. (audience laughing) "And I also understand why, "because you think you can do better, "because you think that, oh, he's not good looking enough".

"And your biochemical algorithm that was shaped in "the African savanna 100,000 years ago, "it gives far too much importance "to external looks, to beauty. "Because this is what mattered in "the African savanna 100,000 years ago, "it was a good indicator of fitness. "And you are still following this old-fashioned algorithm "from the African savanna.

"But my algorithm is much, much better. "I have the latest statistics on relationships "in the post modern world. "And I don't ignore beauty, "I don't ignore good looks.

"But unlike your algorithm, "that gives good looks 30% in weighing, "in evaluating relationships, "I know that the true impact of looks "on the long term success of a relationship is just 11%. "So I took this into consideration, "and I'm still telling you, "that you're better off married". And in the end, it's an empirical question.

Google doesn't have to be perfect, it just have to be better than the average human. It just have to make consistently better recommendations than the decisions people take for themselves. And people often make such terrible mistakes in the most important decisions of their life.

They choose what to study or whom to marry or whatever, and after 10 years, they, "Ah, this was such a terrible mistake". And Google will just have to be better than that. And it won't happen overnight, like in some immediate revolution, it's a process.

We'll ask Google or Amazon or Facebook or whatever, for their advice on more and more decisions, and if we see that indeed we get good recommendations better than the decisions we ourselves usually take, then we trust them more and more, trust them more with our data, and also trust them more with authority to make decisions for us. And it's really happening all around us in small baby steps. Like if you think about finding your way around town.

So more and more people delegate this responsibility to Google Maps or to Waze, or some other GPS application. You reach an intersection, your gut instinct tells you turn right, Google Maps tells you, "No, no, no, turn me left. "I know that there is a traffic jam on the right".

And you trust your intuition, and you turn right and your late. Next time, you say, "Okay, I'll try Google Maps", and you follow Google's recommendation and you arrive on time, you learn not to trust your intuition, it's better to trust Google. And very soon, people reach a point, when they have no idea where they are, they lose their spatial ability to know where they are and find their way around space.

They just follow blindly whatever the application is telling them. And if something happens and the smartphone shuts down, they are clueless. They don't know to find the way around space.

This is happening already today, and it's not because some government forced us to do it, it's decisions we are all taking on a daily basis. Now, two caveats before I open the floor for your questions. First of all very important to emphasize that all this depends on the idea that we are in the process of hacking the human being, and in particular, of hacking the human mind and the human brain.

But we are still very, very far from understanding the brain and even further from understanding the mind. And there is a chance that in the end, it will turn out that organisms aren't algorithms after all. There are some very deep things we still don't understand about the brain and the mind, and all this dream will turn out to be a fantasy.

So this is the first thing we need to take into account, we still, we are not yet there yet, really understanding the human brain and the human mind. The other important thing to bear in mind, is that technology is never deterministic. You can use the same technology in order to create very different kinds of societies.

This is one of the chief lessons of the 20th century. You could use the technology of the 20th century, of the Industrial Revolution, trains and electricity and radio and cars and so forth. You could use that to create a communist dictatorship or a fascist regime or a liberal democracy.

The trains did not tell you what to do with them. You have here a very famous image. This is East Asia.

An image of East Asia at night taken from outer space from a satellite. And what you see the bottom right corner is South Korea, a sea of light. And in the top corner you see China, another sea of light.

And in between the dark part, it's not the sea, this is North Korea. Now why is North Korea so dark, while South Korea is so full of light? It's not because North Koreans haven't heard about electricity or light bulbs.

It's because they chose to do very different things with electricity than the people in South Korea or in China. So this is a very visual illustration of the idea that technology is not deterministic. And if you don't like some of the scenarios, some of the possibilities that I've outlined in this talk tonight, you should know that you can still do something about it.

So thank you for listening, and we now have time for some questions.

Related Videos

44:18

Yuval Noah Harari on AI, Future Tech, Soci...

Yuval Noah Harari

228,101 views

58:48

Yuval Noah Harari | 21 Lessons for the 21s...

Talks at Google

2,911,050 views

28:21

The Future of Humanity - with Yuval Noah H...

The Royal Institution

964,240 views

1:11:12

Why the world isn't fair: Yuval Noah Harar...

GZERO Media

38,233 views

1:27:15

Yuval Noah Harari on the myths we need to ...

Intelligence Squared

1,835,924 views

1:07:32

Yuval Noah Harari & Ian Bremmer at The 92n...

Yuval Noah Harari

428,551 views

31:41

The Politics of Consciousness | video lect...

Yuval Noah Harari

508,290 views

36:27

Rory Stewart Attempts to Explain the Histo...

The Rest Is Politics

2,027,254 views

22:35

Yuval Noah Harari: 'There is a battle for ...

Sky News

241,585 views

1:22:37

Disruption, Democracy and the Global Order...

CSER Cambridge

132,531 views

![How Did The Wealthy Gain Power In The Past? - Yuval Noah Harari [2015] | Intelligence Squared](https://img.youtube.com/vi/TYAKHLrr51w/mqdefault.jpg)

18:17

How Did The Wealthy Gain Power In The Past...

Intelligence Squared

135,844 views

56:36

Yuval Harari erzählt die Geschichte von mo...

SRF Kultur Sternstunden

1,346,481 views

13:27

Yuval Noah Harari: The 2021 60 Minutes int...

60 Minutes

897,260 views

1:23:14

New Religions of the 21st Century | Yuval ...

Talks at Google

1,256,904 views

1:23:19

Natalie Portman and Yuval Noah Harari in C...

Yuval Noah Harari

1,913,897 views

1:22:08

The Nature of Reality: A Dialogue Between ...

ICE at Dartmouth

2,532,966 views

41:21

AI and the future of humanity | Yuval Noah...

Yuval Noah Harari

2,223,213 views

46:13

Yuval Harari - The Challenges of The 21st ...

The Artificial Intelligence Channel

254,082 views

1:11:27

TimesTalks | Yuval Noah Harari

New York Times Events

317,489 views

31:34

Lee Berger - New discoveries in human orig...

GLEX Summit

231,678 views