Nanga Parbat 1934 Expedition Disaster

1.16M views3977 WordsCopy TextShare

Scary Interesting

8000m. Otherwise known as the death zone, this is an altitude that can no longer sustain human life....

Video Transcript:

The Death Zone at 8,000 meters or 26,247 feet, air pressure drops to less than 30% of what it is at sea level. This condition means that it's no longer suitable to sustain human life. In other words, in the Death Zone, your body begins to die.

Without supplemental oxygen, your oxygen-starved cells can no longer function, resulting in organ failure and eventually, total body shutdown. There are only 14 places anywhere on Earth where the Death Zone is reachable by land. These are the infamous 8,000-meter peaks.

As a result, these mountains are also considered the pinnacle of mountaineering accomplishments. So in today's video, we're gonna go over one of the earliest attempts to conquer one of these peaks, the 1934 Nanga Parbat expedition. As always, viewer discretion is advised.

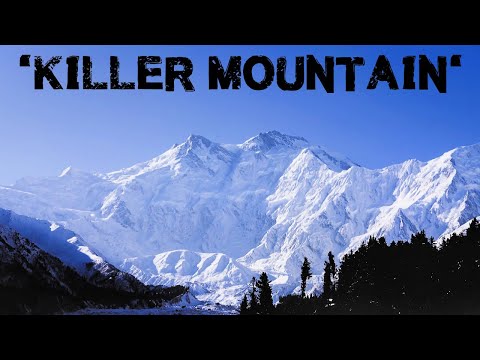

[music] Nanga Parbat. In Urdu, this name means "Naked Mountain". Known to the local simply as "Diamer", but the mountain has another name.

Among the world's finest mountaineers, the mountain has been given the more sinister name "Killer Mountain" for all the deaths that occurred early in the attempts to conquer it. Nanga Parbat is also the western most peak in the Himalayas and resides in the Pakistan administered region of Kashmir, which is just north of both India and Pakistan. As the ninth highest mountain on Earth, this means it is also one of the fabled 8,000-meter peaks and also one of the only mountains on Earth that possesses a so-called Death Zone.

And although most mountains are visually striking, Nanga Parbat is unique in that it's North face, known as the Rupal face, rises 15,000 vertical feet (4572 m) above the base. This might be the largest single vertical rock face anywhere on Earth. Nanga Parbat is also one of only two mountains to be ranked in the top 20 in both height and prominence, meaning that not only is it massive, but this massive height is also fully displayed in the surrounding area.

The most iconic view of this prominence is the famous Fairy Meadow where the crystalline icy face rises from a picturesque deep green meadow in the valleys below. The contrast is striking and only possible because of the size of the face and the way that it rises above the surrounding area. The mountain is also much more accessible than some of the other 8,000-meter peaks.

Take K2, for example, where summit hopefuls have to travel hundreds of kilometers from the nearest populated area to even reach the base. As a result of this accessibility, Nanga Parbat was the ideal choice for the premier mountaineers of the time following the influx of European mountaineers to the Himalayas. The first attempt was in 1895, but the expedition ended in tragedy after three of the members of the group were swept down the mountain to their deaths in an avalanche.

The next attempts wouldn't occur again all the way until the 1930s, this time by German mountaineers. At the time, only British mountaineers were given access to Everest, and several of the other 8,000-meter peaks were attempted unsuccessfully and determined to be too difficult. So Nanga Parbat was the next best choice, because it was 8,000 meters, and as of yet, still unclimbed.

The first of these expeditions was in 1932 by a team of eight of the best alpinists in the world. All of them had significant experience in the Alps and other ranges across Europe and Asia. However, none of them had experience in the Himalayas, which are an entirely different animal logistically.

First, many of these errors require explicit permission from the local government to even access the peaks. Then, there's the general difference in infrastructure that exists even today because some of these areas are simply underdeveloped as a result of poverty. This means that roads, supplies, gear, and even experienced help are either nonexistent or lower quality.

As a result, climbers of the area had to bring much of their equipment with them. And on these peaks, this is truly an immense amount of gear. Oftentimes, literal tons of gear, which requires dozens, sometimes hundreds of locals to carry the gear to the base of the mountains.

The locals hired for this purpose are known as porters. The pay is minimal compared to what would be paid to the locals of the climbers' own native countries, but it's still much more than what the local porters of the region could earn otherwise. But in exchange for these high wages, the work is very hard and very dangerous.

From the start of the 1932 expedition, there were logistical issues. The team had trouble acquiring the right permits, which meant that they had to take a long detour to even reach the mountain. Some of the gear they brought for the porters were stolen.

The weather was poor the majority of the time, and the base camp was hit by multiple avalanches. Over the course of this attempt, the team established a total of seven camps at different altitudes and ultimately reached 23,000 feet (7010. 4 m) before the weather was too bad to continue.

By then, many of the porters were in terrible shape due to altitude sickness, and the mountaineers themselves were not much better. One porter was said to only be able to walk a few feet before collapsing in the snow for a long period of time. The climbers, not used to such high altitudes either, would take a single step, and then five hard breaths before being able to take another.

At the onset of the first storm, the team spent several weeks waiting and faring equipment up and down between different camps, waiting to make a final push. Finally, even two of the climbers had to leave and nine of the 12 total porters were too sick to continue, bringing an end to their journey. This attempt was led by a man named Willy Merkl, and following his defeat, he almost immediately started planning his next attempt.

Two years later, in 1934, Merkl had assembled a new team of nine climbers, including himself and several scientists to make another attempt at the Killer Mountain. Unlike the previous expedition, this time, the team hired 35 trained and hardened Sherpa and Bhutia porters, many of whom participated in one or another of the famous early Himalayan expeditions. These were men who had experience in the mountains and were fit and well trained technically.

Then, on the 2nd of May, the entire group assembled in the city of Srinagar to make the final preparations. In addition to the experienced porters, 600 locals were hired to carry 570 loads of equipment for the 200-mile (322 km) walk to the base of Nanga Parbat. This route would take them in a semi-circle north of Srinagar, east around the mountain, and then finally, to the northeast side of the mountain itself.

This was also no ordinary walk. Winter is longer and harsher in the mountains, meaning that in May when they were traveling through the 10,000-foot (3,048 m) mountain passes, on the way there, the snow was still deep. Over the weeks of walking, porters collapsed from exhaustion until finally, the icy giant was visible in the distance across the valley as they walked over the famous Raikot Bridge.

17 days after leaving Srinagar, base camp was established in the serene grassy Fairytale Meadow at 13,000 feet (3,962 m). They now had 13,000 more to go to be the first ever to set foot on the summit of Nanga Parbat. As the train of supplies continued to arrive, some individuals stayed behind to set up camp, while another group, known as the advanced party, set off up the mountain to establish the root and next camps.

This group consisted of four climbers and 16 porters, and this first push took them through the massive Rakhiot Glacier. In this labyrinth of towering ice boulders and deep gouging crevasses, the team encountered dead-end after dead-end until finally discovering a safe passage. And despite the difficulty of the glacier, the weather stayed sunny in about 10 degrees below freezing.

So eventually, camp two was established beyond the glacier at 17,500 feet (5,334 m). From the point at which each camp was established, porters worked tirelessly to bring supplies higher up the mountain and ready to use. In the good weather, camp three was quickly established and it seemed as though camp four would be established in no time.

Everything was going almost too smoothly. Unfortunately, this notion was quickly shattered on the 7th of June. For the past day or so, a man named Alfred Drxel had been suffering from altitude sickness, which didn't seem serious initially.

At camp three, the decision was made to bring him back down to camp two in hopes of improving his condition. But by the time he arrived, he had a violent headache that only worsened as the day went on. And although he tried to brush it off, the other could tell how bad his condition had gotten in such a short period of time.

A message was sent to base camp, urging the team doctor to head up as soon as possible, and a porter named Pasang Kikuli, a legend of the area and just 23 years old at the time, brought the doctor up the following day in the afternoon. Then, at the doctor's request, Kikuli made another trip that evening in the dark and in the maze of the Rakhiot Glacier to get oxygen. He finally made it back at 3:00 AM but by then, it was too late.

Drxel's condition continued to worsen until 9:00 AM when he finally died of pulmonary edema. The thing about altitude is that as you ascend, air pressure decreases. The human body adapt to the pressure at sea level.

The result of this is that as air pressure decreases, pressure increases in the blood vessels and capillaries, causing fluid to actually leak out of the vascular tissues. In the lungs, this impedes oxygen intake, and the end result is something similar to drowning or suffocation. Drxel would die in the arms of his companions and his death would be a reminder of the seriousness of the task at hand.

The team spent a few days on a burial and funeral, and so despite their aggressive start, it wouldn't be until June 22nd that camp four was finally established at 20,000 feet (6,096 m) and would serve as their advanced base camp. On mountains as large as Nanga Parbat, the distances climbers have to travel are too great to do in a single day. It's for this reason that camps are even established.

Climbers will sleep and eat at these camps and travel sequentially higher over the course of days and weeks. These camps tend to get smaller as you travel up the mountain as less and less equipment is needed and more equipment has been used up. Advanced base camp would serve as the final large camp where the majority of the equipment stayed as a jumping off point for higher pushes.

If need be, climbers could always return to this advanced base camp where there would be shelter, food, supplies, and help. From camp four, the team ascended farther along the main ridge where they set up camp five at 22,000 feet. This was almost directly underneath another peak in the area known as Rakhiot Peak, and would be the beginning of the challenging climbing.

The route would now take them a treacherously steep ice slope that required that they actually cut steps in the ice for the porters. Ropes will then be fixed into the ice as an additional safety measure because any mistake on this slope would send them falling thousands of feet down the mountain. On July 1st, the advanced team set out up the face, cutting steps, fixing pitons, and laying over 600 feet (183 m) of rope.

It's also important to understand just how difficult things are at this altitude. At just 16,000 feet (4,879 m), the air pressure is already half of what it is at sea level. So as you travel higher, it's as though your fitness is decreasing or you're carrying more weight on your back at all times, which is only compounded by the fact that these slopes are impossibly steep.

And oftentimes, these men were actually carrying heavy rucksacks. For just a few hundred vertical feet, it took the advanced team the entire day to prepare the route. Then, on the morning of July 4th, the team set off up to camp six at 22,800 feet (6,949 m).

And although the porters were excellent, the gradient of the slope made this section extremely difficult for everyone. When they finally reached camp six, they stood directly across from the breathtaking Rakhiot Face that was 15,000 feet of sheer ice. With how good the weather had been so far and how successfully each push had been, the team estimated just three or four more days until the summit.

Unfortunately, just a couple thousand feet below the Death Zone now, and with the air ever thinning, the men were starting to get sick. That day, three porters would need to head down due to altitude sickness. Then, the following morning, two more were so sick that they needed to be escorted down the terrible slope of Rakhiot Peak.

Upon reaching camp five, the climber who accompanied them saw that dark clouds had completely obscured the view between camp five and lower down the mountain. Looking up the mountain, though, the skies were still clear. They just had to hope the storm wouldn't travel upward.

Their next task was a long, moderately sloped ridge between Rakhiot Peak to an area known as a Silver Saddle at 23,500 feet (7,163 m). This is a large U-shaped depression that sits about halfway between Rakhiot Peak and the true summit. Then, in the morning of Friday, July 6th, five European climbers and 11 porters set out across the icy rocky ridge.

Even some of the European climbers were having trouble breathing now, and as they got to the Silver Saddle, the wind started to get very strong, likely from the storm brewing down below. Two of the European climbers went on ahead and scouted for a new camp, different than the spot they intended that would provide more shelter from the wind. When they eventually stopped, it looked as though they were just a few hours from the summit, making a summit push hopeful for the following day.

But despite clear skies, the wind continued to get worse throughout the night, to the point that it was as if a hurricane was raging outside their tents. That night, the poles of their tents bent and snapped, and the wind was so strong that it even prevented them from exiting and tying the tents down. Still, the men were optimistic about their chances.

A brief break in the weather was all that they needed to make a summit push. But as is often the case, the following morning, the storm only grew stronger. By then, the men had already realized there would be no attempt that day.

The storm had gotten so bad that it was dark outside at lunchtime. Thankfully, despite the horrible conditions outside, their clothing was enough for them to be warm inside their tents. It was too cold to light the stove to prepare warm food, but they had enough cold food to last five days at least.

But over the course of the day, the storm grew stronger and stronger. If there was no break, they would slowly freeze. It's impossible to stay warm even with the best equipment if you're not moving and not eating hot food.

The morning of the following day - now, Sunday the eighth, Willy Merkl ordered everyone to head back down to camp four, and so the men set out in hurricane force winds, extreme cold, and blinding snow that reduced visibility to just 30 feet (9. 14 m). As with before, the group divided into two.

First was the advanced team of two Europeans and three porters to make tracks to the deep and newly fallen snow. Next were the final three European climbers and the last of the porters. One of these Europeans would follow up the rear to ensure that if anyone fell, they would be caught before falling too far.

And although everyone was still strong, the wind and reduced visibility required that they use extreme caution on the steep slopes. In one instance, one of the porters were torn from the steps below the Silver Saddle and just barely caught by two other men. This not only prevented his death, but also prevented him from pulling the rest of the team down as well.

Unfortunately, even though he was caught, the sleeping bag that he had tied to him was blown away when he fell. This meant that there was now only one bag for all of them. It was now crucial that they all reached camp four or five that night.

They wouldn't be able to survive the night with just a single sleeping bag. It was just too cold. Some of them would surely freeze to death.

Now, just below the Silver Saddle, the two front men unroped from their porters to stay closer to them. The wind kept washing away the tracks they made, so their porters kept making long, difficult detours, trying to find the way. With them unroped, they could stay closer and keep them from making so many unnecessary wrong turns.

Then, finally, in the evening of that day, those two front European climbers stumbled into camp four, covered in ice and exhausted. Their porters weren't with them, but they assumed that they were right behind them, just ahead of the second group. But group two never showed up.

It wouldn't be until much later that the full sequence of events was finally pieced together. And I have to warn you, there are many moving pieces in this next section, making it a bit difficult to follow. It's for this reason that I mostly left names out of this story.

Otherwise, there would be 20 or so names to keep track of as the group splintered into pieces. The camp that the full group turned back from that morning was camp eight, just ahead of the Silver Saddle. The lead group unroped from their three porters between camp seven and camp eight.

But these porters went no further than camp seven. They would stay the night in the tent at camp seven. The second group consisting of the three Europeans and remaining porters never even got to camp seven.

They had to set up a camp between seven and eight, which we'll call camp 7. 5. Unfortunately, one porter from this group would die that night in camp 7.

5 because of how terrible the conditions were. In these higher camps, the men were exhausted, they were frostbitten, and they were starting to become hypothermic. On the morning of the ninth, now one day after turning back, three of the porters were too sick and too snow blind to continue, so they stayed at camp 7.

5. The remaining three Europeans and four porters set off toward camp seven. One of these European climbers would unfortunately die just 50 feet (15.

24 m) from camp seven. He was so exhausted, he simply knelt down in the snow and froze to death. This tent was also so small that there wasn't enough room for the full group, meaning that a few of them would need to go farther down.

The porters were now in better shape than the two European climbers, so they went down to camp six instead. That same morning, the three porters from the lead group who stayed at camp seven left and continued down the mountain for camp six as well. So when the second group arrived, they had already left.

Eventually, all of the remaining porters would be camped close together without realizing it. The lead group of porters was at camp six, and the second group of porters made camp in a snow cave just before camp six. The following day, now Tuesday, July 10th, these two groups of porters joined together and all seven of them were seen traveling down the mountain in one group.

Upon seeing them, rescuers were sent up from camp four to meet them and help them down. But by the time they finally reached them, only four of the seven were left. Two had died on the steep steps of Rakhiot Peak and one more had tragically died just 10 feet from camp five.

The surviving four were exhausted and their fingers and toes were horribly frostbitten. Of the initial group that turned back a few days prior, just three porters remained at camp 7. 5 and two Europeans remained at camp seven.

Everyone else was either dead or safe at camp four. On Wednesday the 11th, one of the porters at camp 7. 5 would die as well, and the remaining two stayed for one more day before finally heading down for camp seven on Thursday.

When they reached the camp that Thursday on the 12th, the two remaining Europeans were still there as well. Rescuers tried desperately to get higher up the mountain, but the storm was so bad it wouldn't be until the evening of that day that they finally reached camp five. They intended on going up higher to save the remaining men or to bring down bodies, but the storm was so fierce it forced them back down to camp four.

On Friday the 13th, one more of the Europeans died at camp seven, leaving only two porters and the expedition leader, Willy Merkl, left alive. The following morning on Saturday, this group tried to make it down to camp six, but by then, Merkl could barely walk. They would have to shelter in a small ice cave that night in between camp six and camp seven.

Incredibly, down at camp four, the others watched the ridge intently and occasionally saw a single man walking along. Then, he made his way down the treacherous Rakhiot steps, and then finally, by some superhuman effort, into camp four. He managed to tell the others that Merkl and the final porter were still alive somewhere below camp seven.

On Sunday the 15th and Monday the 16th, rescuers tried desperately to reach them, but the newly fallen snow was chest-deep and the storm still raged, preventing them from going any higher. Sometime later, once the storm had finally passed, Merkl's body was located near the Rakhiot steps. His porter's body has never been found.

It's thought that his porter might have survived had he not stopped to help Merkl, but ultimately, sacrificed his life in hopes of bringing Merkl down with him. All in all, the 1934 Nanga Parbat climbing disaster resulted the deaths of 10 individuals. First was Alfred Drxel early in the expedition.

Then, in the storm, three more Europeans died, and a total of six porters. The last remaining survivor, a man named Ang Tsering, battled the storm for over a week before finally making it to safety. The two men who were the last to die likely lost their battle shortly after his salvation.

By the 22nd of July, all of the camps had been removed from Nanga Parbat. And in the words of Willy Merkl's brother Carl on the 1934 Nanga Parbat disaster, the sheer protracted agony has no parallel in mountaineering history. Hello everyone.

My name is Sean and welcome to Scary Interesting. Thank you all so much for watching and hopefully, I will see you in the next one.

Related Videos

19:04

This Object Has A TERRIBLE Secret

Scary Interesting

993,555 views

39:54

Dhaulagiri

Eddie Bauer

1,495,515 views

11:50

2025 Black Canyon 100K Race Highlights

Singletrack

7,714 views

17:35

Why Some Sherpas Say There Won’t Be Any Gu...

Business Insider

5,347,125 views

17:10

Link Sar: The Last Great Unclimbed Mountain

EpicTV

1,835,681 views

46:17

Breathtaking: K2 - The World's Most Danger...

Eddie Bauer

16,127,515 views

21:12

The WORST Mountain Disaster In History | H...

Scary Interesting

1,180,359 views

46:38

The Horrible Truth About Climbing Mount Ev...

Real Stories

423,309 views

48:18

Ghosts of K2

David Snow

2,029,890 views

47:23

Behind The First Summit of The World's Tal...

National Geographic

866,043 views

12:27

The Cairngorm Plateau Disaster | A Short D...

Fascinating Horror

2,325,568 views

28:24

The Most Dangerous Mountain on Earth | K2

Scary Interesting

1,785,283 views

53:36

Why Climbing Mount Everest Is So Expensive...

Business Insider

1,356,706 views

16:29

The Deadliest Mountain on Earth

Scary Interesting

578,921 views

46:07

The Secret History of Auschwitz’s Seven Dw...

Real Stories

336,241 views

19:59

Britain's WORST Mountaineering Disaster | ...

Scary Interesting

960,848 views

1:29:56

The Deadly Race To The Summit Of The Matte...

Wonder

1,407,975 views

47:55

The Inside Story Of Mount Everest's Deadli...

CNA Insider

1,688,995 views

52:20

The Disastrous Attempt To Reach The North ...

Timeline - World History Documentaries

888,580 views

12:35

Annapurna: The Silent KILLER Mountain

Everything Explained

661,871 views