Through the Labyrinth: A Guide to Navigating Chaos and Confusion

46.86k views5690 WordsCopy TextShare

Eternalised

Confusion, wandering, isolation, darkness, disorientation—all evoke the labyrinth, a complex network...

Video Transcript:

“Not all those who wander are lost. ” Confusion, wandering, isolation, darkness, disorientation—all evoke the labyrinth, a complex network of paths in which it is difficult to find one’s way out. Or do they?

Today, the term “labyrinth” is used as a synonym for “maze”, which is technically incorrect. As we’ll see, the labyrinth’s original meaning has been entirely distorted, which is only to be expected from such a perplexing symbol. The labyrinth is an archetype, a primordial image that dates back to the Bronze Age (around 2500 to 2000 BC), making it one of the oldest symbols.

The earliest labyrinths are found in petroglyphs of prehistoric origin, mostly around Europe. In the Spanish province of Galicia many labyrinths appear, some with carvings of deer and other wild animals, perhaps magical symbols for the hunt. In Castilla y León two great rocks are seen with three bizarre labyrinths each.

In Naquane, Italy, a labyrinth from the Iron Age is surrounded by crowds of warriors, in the Tomb of Sardinia we find a labyrinth located in a tomb, suggesting that it could have been a symbol of rebirth or the afterlife, and in a labyrinth of Camonica Valley a man is depicted standing with his arms raised in prayer. These, among many others, can be considered as the first prototypes. Labyrinths are also found constructed from stone and boulders especially in the Nordic countries and Russia, most of which date back to the late Middle Ages (from AD 1300 to 1500).

Today, the labyrinth is found everywhere: in architecture, art, books, movies, and games. The archetypal image of the labyrinth fundamentally expresses the path of life, full of dark corners and unexpected turns. If we overcome them, we are transformed and enlightened – if not, we become disoriented and find life meaningless and Kafkaesque.

This reflects the age-old quest for self-realisation. In the cosmology of the O’odham people, a Native American tribe, the creator god I’itoi is depicted as the figure known as the “Man in the Maze. ” This labyrinth, which he enters through magical means, serves as protection from enemies while still allowing him to come out to help his people in times of great need.

The labyrinth represents life itself, with its twists and turns. Upon reaching the centre, we can look back on the path we had taken. That is when the Sun God comes to bless you and say you have made it, that is when you die and pass into the next world.

From within the labyrinth, the view is extremely restricted and confusing, while from above one discovers a supreme artistry and order. The labyrinth is a paradox that simultaneously incorporates chaos and order. This is one of the reasons why it has been misunderstood.

The labyrinth is most commonly associated with the Minoan civilisation, a Bronze Age culture in the island of Crete, now part of Greece. The classical or archetypal pattern of the labyrinth consists of a single pathway that loops back and forth to form seven circuits. It is also known as the Cretan labyrinth.

The earliest example of this is found in an inscribed clay tablet from the Mycenaean palace at Pylos in southern Greece. Accidently preserved by the fire that destroyed the palace around 1200 BC. On the back of the tablet is written, “One jar of honey to all the gods, one jar of honey to the Mistress of the Labyrinth” (possibly referring to Ariadne).

This seven-course pattern is shown in the labyrinth-decorated coins from Knossos. The word labyrinth comes from the Greek labyrinthos. The earliest known application of this term refers to an enormous structure in Egypt.

The 5th century BC Greek historian Herodotus had visited the labyrinth and claimed that it surpassed even the pyramids. He employs the term, as though it were a generic concept, to describe a large, awe-inspiring, skillfully built, stone complex. The Labyrinth of Egypt, as it is known, was counted among the wonders of the world, and made up a funerary temple that once stood near the foot of the pyramid of the pharaoh Amenemhet III, who ruled around 1800 BC.

It was only through later historians that a connection was made between the Egyptian “labyrinth” and the maze motif, albeit a modest precursor of the maze. The 1st century BC historian Diodorus of Sicily wrote that “a man who enters the labyrinth cannot easily find his way out”, and a century later, Pliny the Elder called it a “bewildering maze of passages”, and stated the Cretan labyrinth was but an imitation of the Egyptian labyrinth, “one hundred times smaller. ” Thus, for the first time, the labyrinth was compared with the confusing passageways associated with a maze.

The descriptions of these later authors of such paths are not accounts of personal experiences but reflect the development of ideas now linked to the labyrinth concept. In Plato's dialogue Euthydemus, written around 400 BC, the labyrinth is used as a metaphor in a matter-of-fact way: “then we got into a labyrinth, and when we thought we were at the end, came out again at the beginning, having still to seek as much as ever. ” This metaphor is based on how one moves in a classical labyrinth, which has a single course (unicursal) guaranteeing an unobstructed progress, albeit often by the most complex and winding of routes.

But there are no wrong turns possible, and by following the path, you eventually reach the centre. This is the labyrinth in its true and original form, with the earliest prototypes dating back to the Bronze Age. Mazes, on the other hand, date back to the late medieval period, and have multiple courses (multicursal).

They confuse us with multiple choices, dead ends and the threat of getting lost. The word maze likely derives from the Old English word mæs “confusion or bewilderment” which in turn comes from the Old Norse word mása. This is where our word “amazement” comes from.

The earliest maze designs were apparently used as defensive structures, for military purposes. Similarly, in the Hindu epic Mahabharata, the longest poem ever written, the chakra-vyūha (wheel formation) is a labyrinthine military formation of multiple defensive walls, it has seven layers of soldiers who rapidly move clockwise and anticlockwise so that all enemies are confused and trapped within this deadly spinning machine. The outer layers are manned by ordinary soldiers, while the inner layers contain elite warriors and at the centre is the commander-in-chief.

Designed for defense, it also has offensive elements. During the great battle, Abhimanyu, Arjuna’s son, learned how to penetrate this battle formation, but did not know how to find his way out again. Despite fighting bravely and reaching the centre, he was overwhelmed by the enemy on all sides and killed.

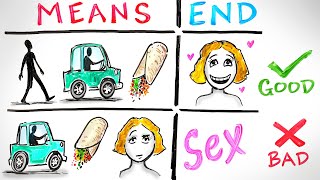

One must not tackle an initiation test for which one is not yet prepared. The labyrinth is associated with order, and the maze with chaos. This makes them opposites.

The experience of navigating a labyrinth is predictable, as there is no possibility of getting lost, only a single journey from start to finish. The maze challenges the navigator to find the correct route among many possible ones, creating a disorienting experience that evokes a feeling of being trapped, and there being no exit – a typical motif in our zeitgeist. For instance, in the immensely popular 2009 dystopian novel The Maze Runner, a boy wakes up in the Maze with no memory and must escape it.

The Maze is described as a massive structure with high, imposing stone walls covered with thick ivy that stretch as far as the eye can see. It is not only filled with long dark corridors and dead ends, but also with deadly creatures, and its walls change every night, making it nearly impossible to memorise or map. The maze embodies the timeless motif of getting lost and not knowing which way to go.

“Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom”, writes Søren Kierkegaard in his book The Concept of Anxiety. He gives us an analogy by imagining a man standing on the edge of a cliff, looking down into the yawning abyss. The man experiences anxiety of freedom in the form of the possibility of falling.

The greater the freedom, the more he is seized by the feeling of dread. As Friedrich Nietzsche stated, “When you stare for a long time into the abyss, the abyss stares back into you. ” This existential anxiety is not a fear of specific things, but rather an abstract and profound sense of disorientation.

You have the potential to choose from a sea of infinite possibilities; the problem is what to choose from. For Kierkegaard, we either lose ourselves in the finite, leading to anxiety through a sense of emptiness from focusing solely on immediate pleasures and concerns, or we lose ourselves in the infinite, where anxiety arises from escaping into spiritual aspirations while neglecting our daily responsibilities and duties. The human being is a synthesis of the finite and the infinite, and thus must balance both.

To quote Nietzsche again, “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how. ” To choose a path in life requires responsibility, which can be a heavy weight to bear. As long as you go with your heart, however, you are doing something meaningful and intended by fate.

We may think that a certain outcome is bad, but as the Stoics emphasise, our perceptions of good and bad are limited. Something that we consider bad, might end up being good, and vice versa. Thus, as Seneca writes in Letters from a Stoic, “we suffer more in imagination than in reality.

” Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges is renowned for his frequent use of the labyrinth symbol. In his novel The Garden of Forking Paths, Borges goes further in the idea of freedom and choice, by exploring the concept of the bifurcating path. Every path you walk in life subsequently divides into two other paths, ad infinitum.

But these do not just follow a linear divergent path, but are also convergent and parallel. All possible outcomes of decisions and events exist simultaneously in a complex branching network of alternate timelines. In other words, the paths that you didn’t walk will not just go on their own course for infinity, but eventually converge with your path.

Time itself is a labyrinth. It is the metaphysical world in which we are all embedded in. There’s no need to build a labyrinth when the entire universe is one.

To better understand the enigmatic symbol of the labyrinth, we must look into its origins in Greek mythology. King Minos of Crete prayed to the sea god Poseidon for a divine sign to prove his right to rule. Poseidon sent a magnificent white bull from the sea, which Minos was supposed to sacrifice in honour of the god.

Enchanted by the bull’s beauty, Minos decided to keep it and sacrifice a different bull instead. This act of defiance angered Poseidon. To punish Minos for his deceit, Poseidon caused his wife, Queen Pasiphae, to fall madly in love with the bull.

Pasiphae's desire was so strong that she enlisted the help of Daedalus, the archetypal master craftsman, to construct a wooden cow for her, allowing her to mate with the bull. The union between Pasiphae and the bull resulted in the birth of Asterius, the Minotaur (literally, “the bull of Minos”), a creature half man and half bull. In classical art it is depicted with the body of a man and the head of a bull, in later developments it is shown with a man’s head and torso on a bull’s body, reminiscent of a centaur.

As the Minotaur grew up, the terrifying beast became increasingly violent and started to devour people. This served as a constant reminder of Minos disobeying the gods. Psychologically, the Minotaur represents the shadow (the unknown, repressed qualities).

Afraid and ashamed of his stepson, Minos asked Daedalus to build a tremendous labyrinth, in which to hide the thing away. So intricate was the invention, that Daedalus himself, when he had finished it, was scarcely able to find his way back to the entrance. This served the king well, enabling him to dispose of his enemies while also hiding and feeding the Minotaur - who would now only eat humans.

When Minos’s eldest son came of age, he travelled to Athens to partake in the so-called Panathenaic Games. Somehow, he died, and Minos blamed Athens for his loss. In reparation, he required that King Aegeus pay him a tribute, every nine years, of seven youths and seven maidens.

These unfortunates, drawn by lots, would be sent to Crete in a ship with black sails, paraded before the people, and cast into the Labyrinth. When the third payment was approaching, the hero Theseus, took the place of one of the youths and volunteered to slay the Minotaur. He set off with a black sail, promising to his father, that if successful he would return with a white sail.

In Crete, Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell in love with Theseus and, on the advice of Daedalus, gave him a clew (a ball of thread or yarn). He tied it at the entrance of the labyrinth, so that he could later escape by following the clew. This gives us the modern word “clue” (that which points the way), and “clueless”.

Ever since, Ariadne’s thread has become the archetypal image for helping one navigate through a confusing or complicated situation. The way out of the labyrinth is to follow the thread of one’s soul. In Jungian terms, Ariadne is the guiding power of the anima (the female soul in man), who helps the hero in his katabasis (descent to the underworld), similar to the role of Beatrice in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

After Theseus kills the Minotaur, he leads the Athenians out of the labyrinth, and they sail away from Crete. Before reaching home, Theseus and the rescued victims celebrate on the islands by performing a peculiar dance called the “Crane Dance”, in which they went through the motions of threading the labyrinth. Theseus abandons Ariadne on the island of Naxos, and Dionysus marries her.

In one of Nietzsche’s last letters before his mental collapse, he wrote to Cosima Wagner: “Ariadne, I love you! ” Signed: Dionysus. Theseus entirely forgets to replace the black sail with the promised white sail, and King Aegeus sees the black-sailed ship approach.

Presuming his son dead, he jumps into the sea that is since named after him. His death secured the throne for Theseus. Minos suspects that Daedalus had revealed the labyrinth’s secrets to Theseus and imprisons him and his son Icarus in the labyrinth.

Daedalus constructed wings for them to escape, and warned Icarus not to fly too close to the sun, or the heat would melt the wax. He ignored his father’s instructions, and fell from the sky, plummeting into the sea, and drowned. Whether this mythical labyrinth actually existed is unknown.

For the original inspiration of this myth, most scholars point to the ruins of the vast palace complex at Knossos, which was central to the Minoan civilisation, discovered by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in the 19th century. The labyrinthine layout, with its many rooms and corridors, was by design rather than accident. The Central Court was regarded as the ‘final destination’ of the people, and likely served as a setting for communal ceremonies.

Reaching it required navigating the symbolic palatial space, a journey that echoes the rebirth experienced at the centre of a labyrinth. In this context, altered states of consciousness were shaped by the environment, not just by inner cognitive processes. A fragment of a fresco with a labyrinth design was discovered in the palace, dating back from 1700 to 1600 BC.

Moreover, the figure of the bull was crucial to the Minoans, the “horns of consecration” symbol is ubiquitous, and it is known that bull-leaping was one of the key rituals in their religion. Though the word labyrinthos remains of unknown origin, scholars have linked it to the Mycenaean Greek term da-pu-ri-to, which traces back to the Minoan word du-pu-re. This term is associated with Mount Ida, known as “the Mountain of the Goddess”, and is connected to sacred caverns, particularly those of Gortyna on Crete.

It has been suggested that caverns were the original inspiration for the mythical labyrinth, though they are maze-like. The French botanist J. P.

de Tournefort writes about visiting this subterranean passage by an inconspicuous hole in the rock in a steep part of Mount Ida, and finding himself in an intricately winding passage. The same place is visited by C. R.

Cockerell, who writes in his journal, “The clearly intentional intricacy and apparently endless number of galleries impressed me with a sense of horror and fascination I cannot describe. At every ten steps one was arrested, and had to turn to right or left, sometimes to choose one of three or four roads. ” The myth of the Minotaur has given us the first inklings of labyrinth symbolism.

However, while myths reflect fundamental patterns of the human psyche, they still incorporate cultural elements that can obscure the deeper archetypal symbolism. As we have seen, caves have been considered as the inspiration for the mythical labyrinth. In his book, Labyrinth: Studies on an Archetype, Gaetano Cipolla supports this idea by highlighting that caves and labyrinths partake of the same symbolism.

Caves, the original homes of early humans, not only served as protective places, but also as sacred spaces for magical rituals and rites of initiation. As the burial sites for their deceased ancestors, caves were closely associated with the underworld or the afterlife. Crossing the threshold into these chthonic realms symbolised a mystical return to Mother Earth, from whose womb all things originate.

Jungian analyst Joseph Henderson writes: “In all cultures, the labyrinth has the meaning of an entangling and confusing representation of the world of matriarchal consciousness; it can be traversed only by those who are ready for a special initiation into the mysterious world of the collective unconscious. ” The labyrinth is connected with birth. Spirals and meanders, precursors to the labyrinth, have been found among the cave paintings of prehistoric peoples, often incised on or near goddess figurines and carved animals.

These labyrinthine spirals indicate the symbolic passageway from the visible realm of the human into the invisible dimension of the divine, retracing the journey souls of the dead would have taken to re-enter the womb of the mother on their way to rebirth. It is no accident that in India, the labyrinth or yantra has traditionally been used as a magical practice to ease the pain of childbirth. For the Hopi native Americans, the labyrinth is a symbol for the Great Mother, birth and reincarnation.

It is possible that the term labyrinth originally denoted a dance whose path was determined by the classical labyrinth pattern, as Hungarian scholar Karl Kerenyi emphasises in his book Labyrinth Studies. This would connect with the Crane Dance. Bodily movement being the primal, most direct form of expression.

This recalls the Nataraja, a depiction of Shiva as the divine cosmic dancer, the dance of life itself, which includes creation, preservation, and the destruction of the universe. The labyrinth is also one of the oldest apotropaic symbols. Almost all Roman mosaic labyrinths depict a fortified city and were often placed near the entrance of a house to ward off evil.

Underlying this is the notion that evil spirits can fly only in a straight line, they are not able to find their way through a labyrinth’s twists and turns. In India, the labyrinth’s magically defensive function is traced to the chakra-vyūha. The labyrinth is the perfect embodiment of initiation rites, which are common in secret societies.

The purpose of the labyrinth’s frequent inclusion in initiatory rites is to temporarily disturb one’s rational consciousness or linear frame of orientation, allowing the non-rational, the instinctual, and the numinous, to guide one’s path to the truth. The interior space is filled with the maximum number of twists and turns possible. The experience of repeatedly approaching the goal, only to be led away from it, causes psychological strain.

Since there are no choices to be made on the path to the centre, those who can stand this strain will inevitably reach their goal. It is often when you are on the verge of giving up, that you are actually nearing a breakthrough. In a labyrinth, one does not lose oneself, one finds oneself.

In reaching the centre, one experiences a symbolic death and rebirth, so that the initiate is born into a new existence. This is expressed in the labyrinth’s serpentine pattern, the continual change of direction from left (the opposite direction in which the sun travels, i. e.

, toward death or unconsciousness) to right (the direction in which the sun travels, i. e. , life or consciousness).

Psychologically, the labyrinth is symbolic of a descent into hell. Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung writes: “The labyrinth is indeed a primordial image which one encounters in psychology mostly in the form of the fantasy of a descent to the underworld. In most cases, however, the topography of the unconscious is not expressed in the concentrated form of the labyrinth but in the false trails, deceptions and perils of an underworld journey.

” This description recalls the Egyptian representation of the underworld. In the Book of Gates, an ancient Egyptian funerary text, the deceased soul has to pass through a mazelike structure with a series of gates and encounter various obstacles, terrifying entities, and trials. The Book of the Dead contains spells and instructions to help the deceased navigate through this realm.

Dante's portrayal of Hell, on the other hand, consists of nine concentric circles, each becoming increasingly torturous as one descends, with Satan residing at the centre. “Midway in the journey of our life, I awoke to find myself alone and lost in a dark wood, having wandered from the straight path. ” These are the famous words of Dante in the Divine Comedy, before he enters the Gates of Hell, above which is inscribed, “Abandon all hope ye who enter.

” Note that Dante says it is “the journey of our life”, that is, it is an archetypal pattern that is shared by all of us. The journey to a dark realm in search of wisdom is universal. Jung’s own dark night of the soul is depicted in The Red Book.

While it may seem that we are alone in this journey outwardly, in the unconscious manifestations, we are always accompanied by other figures, Joseph Campbell writes: “And so it happens that if anyone—in whatever society—undertakes for himself the perilous journey into the darkness by descending, either intentionally or unintentionally, into the crooked lanes of his own spiritual labyrinth, he soon finds himself in a landscape of symbolical figures. ” Paradoxically, you find yourself when you become lost, because that is when most of us turn within for help. The unconscious knows more about us than we know about ourselves.

It is the ultimate source of wisdom and the master pattern of our life. Jung writes: “When no answer comes from within to the problems and complexities of life, they ultimately mean very little. Outward circumstances are no substitute for inner experience.

Therefore, my life has been singularly poor in outward happenings. I cannot tell much about them, for it would strike me as hollow and insubstantial. I can understand myself only in the light of inner happenings.

It is these that make up the singularity of my life. ” When we are without a sense of direction, the world seems like a giant labyrinth. The way out of this massa confusa or inner entanglement, as the alchemists put it, is to reach the centre, the symbol of wholeness par excellence.

The path, however, is never straight but rather serpentine. Jung writes: “[The art requires the whole person] exclaims an old alchemist. It is just this homo totus [whole person] whom we seek… But the right way to wholeness is made up, unfortunately, of fateful detours and wrong turnings.

It is the longissima via [longest path], not straight but snakelike, a path that unites the opposites in the manner of the guiding caduceus, a path whose labyrinthine twists and turns are not lacking in terrors. It is on this longissima via that we meet with those experiences which are said to be “inaccessible. ” Their inaccessibility really consists in the fact that they cost us an enormous amount of effort: they demand the very thing we most fear, namely the “wholeness” which we talk about so glibly and which lends itself to endless theorising, though in actual life we give it the widest possible berth.

” Though we all desire and talk about wholeness, we simultaneously will do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing our own soul. We seek light, only to fall into darkness. We idealise perfection, but life calls for completeness, and, as Jung says, “for this the ‘thorn in the flesh’ is needed, the suffering of defects without which there is no progress and no ascent.

” In the 1672 alchemical work, The Green Lion or The Light of the Philosophers a labyrinth appears as a sanctuary for the philosophers’ stone. Various elements appear, the most important being the sun and moon above the sanctuary, the classical planetary spheres, along with the alchemical symbols for salt, mercury and sulphur (body, spirit, and soul). The planets also stand for metals.

The correspondences between occurrences in the sky and those on earth are seen in a relationship of microcosm-macrocosm. In the foreground is an angel with the thread of Ariadne by which he endeavours to lead the couple into the labyrinth. Here, the labyrinth is a symbol of the difficulties of the “Great Work” of alchemical transmutation.

The alchemists emphasised that the miracle of the stone could only happen Deo concedente (God willing). The centre has always been considered a sacred space. It is where one enters the “special world” and receives new insights about oneself, others, and the world.

We move from the profane to the sacred, as Mircea Eliade puts it. This is where we find the “treasure hard to attain”, “the philosophers’ stone”, the “elixir of life”, “the diamond body”, etc. , symbols of what Jung calls the Self (the God-image or total personality).

As many mystics have pointed out, “He who knows himself knows God”. The centre is a place of the numinous, it is what Rudolf Otto calls mysterium tremendum et fascinans, a mystery that is at once terrifying and fascinating. It is awe-inspiring.

Many people think that to reach the centre is the end goal of self-realisation. But it is in fact only half the journey. Afterwards, one must escape the labyrinth by returning to the beginning, back to the “ordinary world”, but this time as a transformed person, seeing the world with “new eyes”.

It is a spiritual death and rebirth. T. S.

Eliot wrote, “And the end of all our exploring, will be to arrive where we started, and know the place for the first time. ” This is of course, a lifelong cyclical process. The path to individuation is like a labyrinthine spiral, it follows the process of circumambulation, where one moves in a series of concentric circles, that is, circles that share the same centre.

Hermes Trismegistus writes in the Emerald Tablet: “True it is, without falsehood, certain and most true. That which is below is like that which is above, and that which is above is like that which is below, to accomplish the miracle of one only thing. .

. It ascends from the earth to the heaven, and descends again to the earth, and receives the power of the above and below. Thus you will have the glory of the whole world.

Therefore all darkness will flee from you. ” The journey to the centre of the labyrinth is the transition from earth to heaven, and the return is bringing the heavenly into the earthly. Through the principle of correspondence, you bring the material to the spiritual and the spiritual back again to the material, imbuing your life with divine significance.

The same idea exists in the hero’s journey, where after leaving the “ordinary world” and entering the “special world”, one must return with the elixir to the former. The elixir is something for the hero to share with others, or something with the power to heal: wisdom, love or simply the experience of surviving the special world. Similarly, Kierkegaard’s knight of faith does not renounce to the world, but returns to it with full engagement by making a double movement: from finitude to infinity and back again to finitude, so that at every step he makes the movement of infinity.

He possesses an extraordinary faith in God that transcends the world. By the Middle Ages, labyrinths were taken as a symbol of the path to redemption or the path to God. Many were created in churches and cathedrals as architectural features, and a dramatic upsurge of interest surged during the so-called Gothic Revival.

Perhaps the most popular medieval labyrinth is the one in Chartres Cathedral in France, which is seen as a substitute for going on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Here, the labyrinth becomes a symbolic path for a spiritual journey, the twists and turns are the obstacles of the journey toward salvation. During the walk, some describe experiencing time and space differently.

It is as if the labyrinth becomes a liminal space, blurring the boundary between the inner world and the outer world, which metaphysically are the two sides of the same coin (the unus mundus or “one world”). This “inner journey” has commonly been depicted as a pilgrim on a spiritual quest. In the hugely influential 17th century religious emblem book Pia Desideria (Pious Desires), Herman Hugo depicts a pilgrim standing at the centre of a labyrinth.

He seeks the exit in the background, which leads to the “castle of heaven”, above which an angel is guiding the pilgrim with Ariadne’s thread, symbolising God’s Word. What is unique to this design is that the labyrinth walls are in fact the path, upon which the pilgrim must tread. Hence, the danger lies in the possibility of falling off; and, indeed, two figures are shown doing just that, whereas the blind man with his dog – an image of trusting one’s instincts – finds his way.

The beacon on the castle of heaven guides ships at sea; two wanderers are shown attempting to climb the mountain of heaven, one of which is falling down it. Below the engraving appears the motto, “O that my ways were directed to keep thy statutes”. In Matteo Silvaggi’s 1542 woodcut, Labyrinth of Earthly Love, appears Pluto “King of the Underworld” in the flames of Mt.

Etna, with a banderole pointing to the entrance of the labyrinth that reads “first gate”, in the other banderoles is inscribed “lust is burning”, and “self-love”. The centre bears the inscription: “Up unto the face of God. ” Changing the scene from hell to heaven, the Labyrinth of Divine Love, emphasises the love of God, and complete absorption in God.

In his 1623 book Labyrinth of the World and Paradise of the Heart, Czech writer John Amos Comenius depicts an allegory of a Pilgrim’s journey through a city which represents “the Labyrinth of the World”. The protagonist, referred to as the Pilgrim, seeks understanding and meaning in life, in a society plagued with confusion and moral corruption. Guided by Mr Ubiquitous and Mr Delusion, symbols of curiosity and deception, the Pilgrim encounters people consumed by vanity, greed, and moral corruption.

As he witnesses the pursuit of power and status at the cost of integrity, he becomes disillusioned. Then, Christ appears to the Pilgrim so that he may be a light in the world and guide others. The Pilgrim discovers that true peace is found within, in the “paradise of the heart”, and while the world is indeed a labyrinth, the heart can be a paradise when it is aligned with God.

Similarly, John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, published in 1678, follows Christian, a pilgrim weighed down by a heavy burden (symbolising sin), who leaves everything behind to seek salvation. Directed to the narrow gate, he is pursued by Obstinate and Pliable, who intend to bring him back, but he refuses to return to the “City of Destruction”. Obstinate leaves, deeming Christian mad, while Pliable joins him, hoping to partake of the treasures of the “Celestial City.

” On their journey, they fall into the Slough of Despond, a deep bog in which Christian continues to sink, for his burden is heavy. Pliable manages to get himself out and abandons him. But Pliable is ridiculed by his fellow countrymen for retreating after facing the first difficulty.

Christian is rescued by Help and continues his journey. Surprisingly, his burdens are quickly lifted early in the novel. He continues his path to Paradise, facing various challenges such as the Hill Difficulty, the Valley of Humiliation, the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and the River of Death.

The archetype of the labyrinth encompasses various images: the path of life, the Earth Mother, birth, dance, warding off evil, initiation, liminality, the descent into the underworld, symbolic death and rebirth, the journey to the Self, the alchemical Great Work and the pilgrim’s spiritual journey. When we realise that the labyrinthine twists and turns of our life is part of something greater, we can find meaning in them. By realising that it is within that we must seek for happiness, it will also reflect without.

And if you do your duty, you’ll be satisfied; if not, you will be miserable. The way to truth is a solitary journey, but as Jung quoted from an old alchemist, “No matter how isolated you are and how lonely you feel, if you do your work truly and conscientiously, unknown friends will come and seek you. ” By realising the essence of our soul, we simultaneously become connected with all living beings, nature, and the cosmos; in other words, with God, who makes the crooked paths straight.

Related Videos

55:15

How Dreams Can Anticipate Death and Point ...

Eternalised

220,466 views

1:00:00

The Psychology of Animals

Eternalised

195,385 views

11:30

Master Your Own Kingdom - Guy Ritchie & Jo...

After Skool

122,661 views

1:00:57

Is Everyone Conscious in the Same Way?

Simon Roper

169,700 views

32:18

The Defining Story of Our Time

Like Stories of Old

153,408 views

21:50

The ONE RULE for LIFE - Immanuel Kant's Mo...

After Skool

1,728,860 views

52:44

Inner Gold - Alchemy and Psychology

Eternalised

1,202,292 views

17:59

The Paradox of Being a Good Person - Georg...

Pursuit of Wonder

1,213,720 views

44:44

The Psychology of The Magician

Eternalised

637,258 views

53:36

The Psychology of Numbers

Eternalised

884,487 views

11:24

Carl Jung - How to Find Your Soul (writte...

After Skool

1,193,409 views

53:15

Hermeticism: The Ancient Wisdom of Hermes ...

Eternalised

1,880,453 views

41:20

The Psychology of The Wise Old Man (Sage)

Eternalised

313,873 views

48:35

The Psychology of The Paranormal - Carl Jung

Eternalised

357,012 views

35:05

The Psychology of The Shaman (Inner Journey)

Eternalised

782,832 views

2:32:23

What Is Reality?

History of the Universe

1,074,877 views

50:35

The Psychology of UFOs - Carl Jung

Eternalised

148,097 views

29:30

This Is Why You Can’t Go To Antarctica

Joe Scott

5,560,019 views

38:30

The Psychology of The Man-Child (Puer Aete...

Eternalised

2,043,710 views

27:35

The Dark World of Franz Kafka

Eternalised

432,555 views