Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 09 How to Cure Inflation - Full Video

192.98k views8961 WordsCopy TextShare

Free To Choose Network

Inflation results when the amount of money printed or coined increases faster than the creation of n...

Video Transcript:

Hello, I’m Robert McKenzie, at the Harper Library of the University of Chicago. Almost everyone here, like every family in the United States, has suffered one of the great evils of our time-inflation; spiraling prices that bring unemployment, and threaten to undermine the savings of the whole people. Well now, we’ve all agonized about this problem. Milton Friedman has spent many years analyzing it, and he’s convinced he understands the cure, as you’ll see in this film. (Opening music) (Birds singing) MILTON FRIEDMAN: The Sierra Nevadas in California, 10,000 feet above sea level. In the winter, temperatures drop to forty

below zero. In the summer, the place bakes in the thin mountain air. In this unlikely spot, the town town of Bodie sprang up. In its day, Bodie was filled with prostitutes, drunkards and gamblers, part of the colorful history of the American West. A century ago, this was a town of 10,000 people. What brought them here? Gold. If this were real gold, people would be scrambling for it. A series of gold strikes throughout the West brought people from all over the world, all kinds of people. They came here for one purpose and one purpose only... to

strike it rich, quick. But in the process, they built towns and cities in places where nobody would otherwise have dreamed of building a city. Gold built these cities, and when the gold was exhausted, the cities collapsed, and became ghost towns. Many of the people who came here ended up the way they began... broke and unhappy. But a few struck it rich. For them, gold was real wealth. But was it- for the world as a whole? People couldn't eat the gold, they couldn't wear the gold, they couldn't live in houses made of gold. Because there was

more gold, they had to pay a little more gold to buy goods and services. The prices of things, in terms of gold went up. At tremendous cost, at sacrifice of lives, people dug gold out of the bowels of the earth. What happened to that gold? Eventually, at long last, it was transported to distant places only to be buried again under the ground, this time in the vaults of banks throughout the world. There is hardly anything that hasn't been used for money; rock salt in Ethiopia, brass rings in West Africa, cowry shells in Uganda, even a

toy cannon. Anything can be used as money. Crocodile money in Malaysia, absurd isn't it? That beleaguered minority of the population that still smokes may recognize this stuff as the raw material from which their cigarettes are made. But in the early days of the Colonies, long before the United States was established, this was money. It was the common money of Virginia, Maryland and the Carolinas. It was used for all sorts of things. The legislature voted that it could be used legally to pay taxes. It was used to buy food, clothing and housing. Indeed, one of the

most interesting sights was to see the husky young fellows at that time, lug 100 pounds of it down to the docks to pay the costs of the passage of the beauteous young ladies, who had come over from England to be their brides. Now, you know how money is. There's a tendency for it to grow, for more and more of it to be produced, and that's what happened with this tobacco. As more tobacco was produced, there was more money. And as always- when there's more money, prices went up: inflation. Indeed, at the very end of the

process, prices were 40 times as high in terms of tobacco as they had been at the beginning of the process. And as always... when inflation occurs, people complained. And as always, the legislature tried to do something. And as always...to very little avail. They prohibited certain classes of people from growing tobacco. They tried to reduce the total amount of tobacco grown. They required people to destroy part of their tobacco. But it did no good. Finally, many people took it into their own hands, and they went around destroying other people's tobacco fields. That was too much. Then

they passed a law, making it a capital offense, punishable by by death, to destroy somebody else's tobacco. Gresham's Law, one of the oldest laws in economics, was well-illustrated. That law says that cheap money drives out dear money, and so it was with tobacco. Anybody who had a debt to pay, of course, tried to pay it in the worst quality of tobacco he had. He saved the good tobacco to sell overseas for hard money. The result was that bad money drove out good money. Finally, almost a century after they had started using tobacco as money, they

established warehouses, in which tobacco was deposited in barrels, certified by an inspector, according to his views as to its quality and quantity. And they issued warehouse certificates, which people gave from one to another to pay for the bills that they accumulated. These pieces of green printed-paper are today's counterparts of those tobacco certificates, except that they bear no relation to any commodity. In this program, I want to take you to Britain, to see how inflation weakens the social fabric of society; then to Tokyo, where the Japanese have the courage to cure inflation; to Berlin, where there

is a lesson to be learned from the West Germans, and how so-called cures are often worse than the disease; and to Washington, where our government keeps these machines working overtime. And I am going to show you how inflation can be cured. (machines making noise) The fact is, that most people enjoy the early stages of the inflationary process. Britain, in the swinging 60s: there was plenty of money around, business was brisk, jobs were plentiful, and prices had not yet taken off. Everybody seemed happy at first. But by the early 70s, as the good times rolled along,

prices started to rise more and more rapidly. Soon, some of these people are going to lose their jobs. The party was coming to an end. (60s music playing) The story is much the same in the United States, only the process started a little later. We've had one inflationary party after another. Yet we still can't seem to avoid them. How come? (traffic sounds) Before every election, our representatives would like to make us think we are getting a tax break. When they are able to do it, while at the same time- actually raising our taxes, because of

a bit of magic they have in their kit bag. That magic is inflation. They reduce the tax rates, but the taxes we have to pay go up because we are automatically shoved into higher brackets by the effect of inflation. A neat trick: Taxation without representation. BOB CRAWFORD: The more I work, it seems like the more they take off me. I know if I work an extra day or two extra days, what they take in Federal Income Tax alone is almost doubled, because apparently- it puts you in a higher income tax bracket and it takes more

off you. FRIEDMAN: Bob Crawford lives with his wife and three children in a suburb of Pittsburgh. They're a fairly average American family. Don't slam the door, Daphne! MRS. CRAWFORD: All right. DAPHNE: What are you doing? Making your favorite dish. FRIEDMAN: We went to the Crawford's home after he had spent a couple of days working out his federal and state income taxes for the year. For our benefit, he tried to estimate all the other taxes he had paid as well. In the end, though, he didn't discover much that will surprise anybody. BOB CRAWFORD: Inflation is going

up, everything is getting more expensive. No matter what you do, as soon as you walk out of the house, everything went up. Your gas bills keep going up, electric bills, your gasoline, you could name a thousand things that are going up. Everything is going sky high. Your food. My wife goes to the grocery store. We used to live on, say, $60 or $50 every two weeks just for our basic food. Now it's $80 or $90 every two weeks. Things are just going out of sight as far as expense to live on. Like I say it's

getting tough. It seems like every month it gets worse and worse. And I don't know where it's going to end. At the end of the day that I spend nearly $6,000 of my earnings on taxes. That leaves me with a total of $12,000 to live on. That might seem like a lot of money, but five, six years ago I was earning $12,000. FRIEDMAN: How does taxation without representation really affect how much the Crawford family has left to spend after it's paid its income taxes? Well, in 1972 Bob Crawford earned $12,000. Some of that income was

not subject to income tax. After paying income tax on the rest he had this much left to spend. Six years later he was earning $18,000 a year. By 1978 the amount free from tax was larger. But he was now in a higher tax bracket, so his taxes went up by a larger percentage than his income. However, those dollars weren't worth anything like as much. Even his wages, let alone his income after taxes, hadn't kept up with inflation. His buying power was lower than before. That is taxation without representation in practice. UNNAMED INDIVIDUAL: We have among

us a few brothers that are sitting here today that were with us on that committee and I'd like to tell you.... FRIEDMAN: There are many traditional scapegoats blamed for inflation. How often have you heard inflation blamed on labor unions for pushing up wages? Workers, of course, don't agree. UNNAMED INDIVIDUAL: But fellows this is not true. This is subterfuge. This is a myth. Your wage rates are not creating inflation. FRIEDMAN: And he's right. Higher wages are mostly a result of inflation rather than a cause of it. Indeed, the impression that unions cause inflation arises partly because

union wages are slow to react to inflation and then there is pressure to catch up. WORKER: On a day-to-day basis, we try to represent our own members. But that in fact is not the case. Not only can we not play catch up, we can't even maintain a wage rate commensurate with the cost of living that's gone up in this country. FRIEDMAN: Another scapegoat for inflation is the cost of goods coming from abroad. Inflation, we're told, is imported: higher prices abroad driving up prices at home. It's another way government can blame someone else for inflation. But

this argument, too, is wrong. The prices of imports in the countries from which they come are not in terms of dollars, they are in terms of lira or yen or other foreign currencies. What happens to their prices in dollars depends on exchange rates, which in turn reflect inflation in the United States. Since 1973 some governments have had a field day blaming the Arabs for inflation. But if high oil prices were the cause of inflation, how is it that inflation has been less here in Germany, a country that must import every drop of oil and gas

that it uses on the roads and in industry, than for example it is in the United States, which produces half of its own oil? Japan has no oil of its own at all. Yet at the very time the Arabs were quadrupling oil prices, the Japanese people were bringing inflation down from 30 to less than 5% a year. The fallacy is to confuse particular prices, like the price of oil, with prices in general. Back at home, President Nixon understood this. PRESIDENT NIXON: "Now here's what I will not do. I will not take this nation down the

road of wage and price controls, however politically expedient that may seem. Controls and rationing may seem like an easy way out, but they are really an easy way in, for more trouble, to the explosion that follows when you try to clamp a lid on a rising head of steam without turning down the fire under the pot. Wage and price controls only postpone the day of reckoning. And in so doing, they rob every American of a very important part of his freedom.” FRIEDMAN: Now listen to this: NIXON: "The time has come for decisive action, action that

will break the vicious circle of spiraling prices and costs. I am today ordering a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States for a period of 90 days. In addition, I call upon corporations to extend the wage-price freeze to all dividends." FRIEDMAN: Many a political leader has been tempted to turn to wage and price controls despite their repeated failure in practice. On this subject they never seem to learn. But some lessons may be learned. That happened to British Prime Minister James Callahan, who finally discovered that a very different economic myth was wrong. He

told the Labour Party Conference about it in 1976. JAMES CALLAHAN: "We used to think that you could use, spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all candor that that option no longer exists. It only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step. That's the history of the last 20 years." FRIEDMAN: Well, it's one thing to say it. One reason why inflation does so

much harm is because it affects different groups differently. Some benefit and of course they attribute that to their own cleverness. Some are hurt, but of course they attribute that to the evil actions of other people. And the whole problem is made far worse by the false cures which government adopts, particularly wage and price control. The garbage collectors in London felt justifiably aggrieved because their wages had not been permitted to keep pace with the cost of living. They struck, hurting not the people who impose the controls, but their friends and neighbors who had to live with

mounting piles of rat infested garbage. Hospital attendants felt justifiably aggrieved because their wages had not been permitted to keep up with the cost of living. They struck, hurting not the people who impose the controls, but cancer patients who were turned out of hospital beds. The attendants behaved as a group in a way they never would have behaved as individuals. One group is set against another group. The social fabric of society is torn apart, inflicting scars that it will take decades to heal, and all to no avail because wage and price controls, far from being a

cure for inflation, only make inflation worse. Within the memory of most of our political leaders, there's one vivid example of how economic ruin can be magnified by controls, and a classic demonstration of what to do when it happens. Germany, 1945, a devastated country. A nation defeated in war. The new governing body was the Allied Control Commission, representing the United States, Britain, France and the Soviet Union. They imposed strict controls on practically every aspect of life, including wages and prices. Along with the effects of war, the results were tragic. The basic economic order of the country

began to collapse. Money lost its value. People reverted to primitive barter, where they used cameras, fountain pens, cigarettes, whiskey as money. That was less than 40 years ago. This is Germany, as we know it today, transformed into a place a lot of people would like to live in. How did they achieve their miraculous recovery? What did they know that we don't know? Early one Sunday morning, it was June 20th, 1948, the German Minister of Economics, Ludwig Erhard, a professional economist, simultaneously introduced a new currency, today's Deutsche Mark, and at one fell swoop, abolished almost all

controls on prices and wages. Why did he do it on a Sunday morning? It wasn't as you might suppose because the Stock Markets were closed on that day. It was, as he loved to confess, because the offices of the American, the British, and the French occupation authorities were closed that day. He was sure that if he had done it when they were open they would have countermanded the order. It worked like a charm. Within days, the shops were full of goods. Within months, the German economy was humming along at full steam. Economists weren't surprised at

the results; after all, that's what a price system is for. But to the rest of the world, it seemed an economic miracle that a defeated and devastated country could, in little more than a decade become the strongest economy on the continent of Europe. In a sense this city, West Berlin, is something of a unique economic test tube, set as it is deep in Communist East Germany. Two fundamentally different economic systems collide here in Europe, ours and theirs; separated by political philosophies, definitions of freedom and a steel and concrete wall. To digress from inflation, economic freedom

does not stand alone. It is part of a wider order. I wanted to show you how much difference it makes by letting you see how the people live on the other side of that Berlin Wall. But the East German authorities wouldn't let us. The people over there speak the same language as the people over here. They have the same culture. They have the same forebearers. They are the same people. Yet you don't need me to tell you how differently they live. There is one simple explanation. The political system over there cannot tolerate economic freedom. The

political system over here could not exist without it. But political freedom cannot be preserved unless inflation is kept in bounds. That's the responsibility of government, which has a monopoly over places like this. The reason we have inflation in the United States, or for that matter anywhere in the world, is because these pieces of paper, and the accompanying book entry, or their counterparts in other nations, are growing more rapidly than the quantity of goods and services produced. The truth is inflation is made in one place and one place only: here in Washington. This is the only

place were there are presses like this that turn out these pieces of paper we call money. This is the place where the power resides to determine how rapidly the amount of money shall increase. What happened to all that noise? That's what would happen to inflation if we stopped letting the amount of money grow so rapidly. This is not a new idea. It's not a new cure. It's not a new problem. It's happened over and over again in history. Sometimes inflation has been cured this way on purpose. Sometimes it's happened by accident. During the Civil War,

the North, late in the Civil War, overran the place in the South where the printing presses were sitting up, where the pieces of paper were being turned out. Prior to that point, the South had had a very rapid inflation; if my memory serves me right, something like 4% a month. It took the Confederacy something over two weeks to find a new place where they could set up their printing presses and start them going again. During that two-week period, inflation came halt. After the two-week period, when the presses started running again, inflation started up again. It's

that clear, that straightforward. More recently, there's dramatic example of the only effective way to deal with rampant inflation. In 1973, Japanese housewives going to market were faced with an unpleasant fact. The cash in their purses seemed to be losing its value. Prices were starting to soar as the awful story of inflation began to unfold once again. The Japanese government knew what to do. What's more, they were prepared to do it. When it was all over, economists were able to record precisely what had happened. In 1971 the quantity of money started to grow more rapidly. As

always happens, inflation wasn't affected for a time. But by late 1972 it started to respond. In early ’73, the government reacted. It started to cut monetary growth. But inflation continued to soar for a time. The delayed reaction made 1973 a very tough year of recession. Inflation tumbled only when the government demonstrated its determination to keep monetary growth in check. It took five years to squeeze inflation out of the system. Japan had attained relative stability. Unfortunately, there's no way to avoid the difficult road the Japanese had to follow before they could have both low inflation and

a healthy economy. First, they had to live through a recession until slow monetary growth had its delayed effect on inflation. Inflation is just like alcoholism. In both cases, when you start drinking or when you start printing too much money, the good effects come first and the bad effects only come later. That's why in both cases there is a strong temptation to overdo it, to drink too much and to print too much money. When it comes to the cure, it's the other way around. When you stop drinking or when you stop printing money, the bad effects

come first and the good effects only come later. That's why it's so hard to persist with the cure. In the United States, four times in the 20 years after 1957, we undertook the cure. But each time we lacked the will to continue. As a result, we had all the bad effects and none of the good effects. Japan, on the other hand, by sticking to a policy of slowing down the printing presses for five years, was, by 1978 able to reap all the benefits: low inflation and a recovering economy. But there is nothing special about Japan.

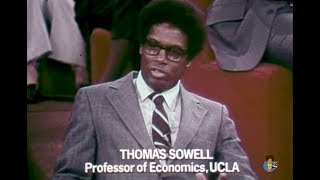

Every country that has had the courage to persist in a policy of slow monetary growth has been able to cure inflation and at the same time achieve a healthy economy. ROBERT MCKENZIE: And here at the Harper Library of the University of Chicago, our distinguished guests have their own ideas, too. So, lets join them now. CONGRESSMAN CLARENCE BROWN: If you could control the money supply, you can certainly cut back or control the rate of of inflation. I'd have to say that that prescription is a little bit easier to write than it is to fill. I think

there are some other ways to do it and I would relate the money supply -- I think inflation is a measure of the relationship between money and the goods and services that money meant to cover. And so if you can stimulate the goods, the production of goods and services, it's helpful. It's a little tougher to control the money supply, although I think it can be done, than just saying that you should control it, because we've got the growth of credit cards, which is a form of money, created, in effect, by the free enterprise system. It

isn't all just printed in Washington, but that may sound too defensive. I think he was right in saying that the inflation is Washington-based. MCKENZIE: Mr. Martin, nobody has been in the firing line longer than you, 17 years head of the Fed. Could you briefly comment on that and we'll go around the group? WILLIAM MARTIN: I want to say 19 years. (Laughter) MARTIN: I wouldn't be out here if it weren't for Milton Friedman, today. He came down and gave us advice from time to time. MILTON FRIEDMAN: You've never taken it. (Laughter) MCKENZIE: He's going to do

some interviewing later, I warn you. MARTIN: And I'm rather glad we didn't take it - (Laughter) -- all the time. BERYL SPRINKEL: In your 19 years as Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Bill, the average growth in the money supply was 3.1 percent per year. The inflation rate was 2.2 percent. Since you left, the money supply has exactly doubled. The inflation rate is, average, over 7 percent, and, of course, in recent times the money supply has been growing in double-digit territory, as has our inflation rate. OTMAR EMMINGER: May I, first of all, confirm two facts which

have been so vividly brought out in the film of Professor Friedman; namely, that at the basis of the relatively good performance of Western Germany were really two events: One, the establishment of the new sound money, which we tried to preserve as sound afterwards. And, secondly, the jump overnight into a free market economy without any controls over prices and wages. These are the two fundamental facts. We have tried to preserve monetary stability by just trying to follow this prescription of Professor Friedman; namely, monetary discipline, keeping monetary growth relatively moderate. I must, however, warn you, it's not

so easy as it looks if you just say, governments have to have the courage to persist in that course. FRIEDMAN: Nobody does disagree with the proposition that excessive growth in money supply is an essential element in the inflationary process and that the real problem is not what to do, but how to have the courage and the will to do it. And I want to go and start, if I may, on that subject, because I think that's what we ought to explore. Why is it we haven't had the courage and don't, and under what circumstances will

we? And I want to start with Bill Martin because his experience is a very interesting experience. His 19 years was divided into different periods. In the first period, that average that Beryl Sprinkel spoke about, averaged two very different periods. An early period of very slow growth and and slow inflation; a later period of what at the time was regarded as creeping inflation, now we'd be delighted to get back to it. People don't remember that at the time that Mr. Nixon introduced price and wage controls in 1971 to control an outrageous inflation, the rate of inflation

was four-and-a-half percent per year. Today we'd regard that as a major achievement. But the latter part of the period when you were chairman was a period when the inflation rate was starting to creep up and money growth rate was also creeping up. Now if I go from your period, you were eloquent in your statements to the public, to the press, to everyone, about the evils of inflation, and about the determination of the Federal Reserve not to be the architect of inflation. Your successor, Arthur Burns, was just as eloquent. Made exactly the same kinds of statements

as effectively, and again over and over again said the Federal Reserve will not be the architect of inflation. His successor, Mr. G. William Miller, made the same speeches and the same statements and the same protestations. His successor, Paul Volcker, he is making the same statements. Now my question to you is: Why is it that there has been such a striking difference between the excellent pronouncements of all chairmen of the Fed-- therefore it's not personal on you, you have a lot of company, unfortunately for the country-- why is it that there has been such a wide

diversion between the excellent pronouncements on the one hand, and what I regard as a very poor performance on the other? MARTIN: Because monetary policy is not the only element. Fiscal policy is equally important. FRIEDMAN: You're shifting the buck to the Treasury. MARTIN: Yes. FRIEDMAN: To the Congress. FRIEDMAN: We'll get to Mr. Brown, MARTIN: Yeah, that's right. FRIEDMAN: don't worry. (Laughter) MARTIN: The relationship of fiscal policy to monetary policy is one of the important things. McKENZIE: Would you remind us, the general audience, when you say "fiscal policy", what you mean in distinction to "monetary policy"? MARTIN:

Well, taxation. MCKENZIE: Yeah. MARTIN: The raising revenue. FRIEDMAN: And spending. MARTIN: And spending. FRIEDMAN: And deficits. MARTIN: And deficits, yes, exactly. And I think that you have to realize that when I've talked for a long time about the independence of the Federal Reserve, that's independence within the government, not independence of the government. And I've worked consistently with the Treasury to try to see that the government is financed. Now this gets back to spending. The government says they're gonna spend a certain amount, and then it turns out they don't spend that amount. It doubles. FRIEDMAN: The

job of the Federal Reserve is not to run government spending; it's not to run government taxation. The job of the Federal Reserve is to control the money supply and I believe, frankly, I have always believed, as you know, that these are excuses and not reasons for the performance. MARTIN: Well that's where you and I differ, because I think we would be irresponsible if we didn't take into account the needs and what the government is saying and doing. I think if we just went on our own, irresponsibly, I say it on this, because I was in

the Treasury before I came FRIEDMAN: I know. I know. MARTIN: to this -- go to the Fed; and I know the other side of the picture. I think we'd be rightly condemned by the American people and by the electorate. FRIEDMAN: Every central bank in this world, including the German Central Bank, including the Federal Reserve System, has the technical capacity to make the money supply do over a period of two or three or four months, not daily, but over a period, has the technical capacity to control it. (Several people talking at once.) FRIEDMAN: I cannot explain

the kind of excessive money creation that has occurred, in terms of the technical incapacity of the Federal Reserve System or of the German Central Bank, or of the Bank of England, or any other central bank in the world. EMMINGER: I wouldn't say technically we are incapable of doing that, although we have never succeeded in controlling the money supply month by month. But I would say we can technically control it half yearly, from one half-year period to the next and that would be sufficient - FRIEDMAN: That would be sufficient. EMMINGER: -- for controlling inflation. EMMINGER: However,

I - VOICE OFF SCREEN: It doesn't move. FRIEDMAN: I'm an economic scientist, and I'm trying to observe phenomena, and I observe that every Federal Reserve chairman says one thing and does another. I don't mean he does, the system does. McKENZIE: Yeah. How different is your setup in Germany? You've heard this problem of governments getting committed to spending and the Fed having, one way or the other, to accommodate itself to it. Now what's your position on this very interesting problem? EMMINGER: We are very independent of the government, from the government, but, on the other hand, we

are an advisor of the government also on the budget deficits, and they would not easily go before Parliament with a deficit which much of it is openly criticized and disapproved by the same bank. Why? Because we have a tradition in our country that we can also publicly criticize the government on this account. And second, if, as has happened in our case too, the government goes beyond what is tolerable for the sake of overall equilibrium, we have let it come through in the capital markets; that is to say, they have driven up interest rates. That has

drawn public criticism and that has had some effect on their attitude. FRIEDMAN: I think that is a very important point that Dr. Emminger just made, because there is not a one-to-one relationship between government deficits and what happens to the money supply at all. The pressure on the Federal Reserve comes indirectly. It comes because large government deficits, if they are financed in the general capital market, will drive up interest rates, and then we have the Wright Patmans in Congress and their successors pressuring the Federal Reserve to enter in and finance the deficit by printing money as

a way of supposedly holding down interest rates. Now before I turn to Mr. Brown and ask him that, I just want to make one point which is very important. The Federal Reserve's activities in trying to hold down interest rates have put us in a position where we have the highest interest rates in history. It's another example of how, of the difference between the announced intentions of a policy, and the actual result. But now I want to come to Clarence Brown and ask him, shift the buck to him, and put him on the hot seat for

a bit. The government spending has been going up rapidly, Republican administration or Democratic administration. This is a nonpartisan issue, it doesn't matter. Government deficits have been going up rapidly, Republican administration or Democratic administration. Why is it that here again you have the difference between pronouncements and performance? There is no Congressman, no Senator, who will come out and say, "I am in favor of inflation." There is not a single one who will say, "I am in favor of big deficits." They'll all say, “We want to balance the budget, we want to hold down spending, we want

an economical government.” How do you explain the difference between performance and talk on the side of Congress? BROWN: Well first I think BROWN: we have to make one point. I'm not so much with the government as I am against it. FRIEDMAN: I understand. BROWN: As you know, I'm a minority member of Congress. FRIEDMAN: Again, I'm not -- I'm not directing this at you personally. BROWN: I understand, of course; and while the administrations, as you've mentioned, Republican and Democratic administrations, have both been responsible for increases in spending, at least in terms of their recommendations, it is

the Congress and only the Congress that appropriates the funds and determines what the taxes are. The President has no authority to do that, and so one must lay it at the feet of the U.S. Congress. Now, I guess we'd have to concede that it's a little bit more fun to give away things than it is to withhold them. And this is the reason that the Congress responds to a general public that says, "I want you to cut everybody else's program but the one in which I am most particularly interested. Save money, but incidentally, my wife

is taking care of the orphanages and so lets try to help the orphanages," or whatever it is. Let me try to make a point, if I can, however, on what I think is a new spirit moving within the Congress and that is that inflation, as a national affliction, is beginning to have an impact on the political psychology of many Americans. Now the Germans, the Japanese, and others have had this terrific postwar inflation. The Germans have been through it twice, after World War I and World War II, and it's a part of their national psyche. But

we are affected in this country by the depression. Our whole tax structure is built on the depression. The idea of the tax structure in the past has been to get the money out of the mattress, where it went after the banks failed in this country and jobs were lost, and out of the woodshed or tin box in the back yard, get it out of there and put it into circulation. Get it moving, get things going. And one of the ways to do that was to encourage inflation, because if you held on to it, the money

would depreciate; and the other way was to tax it away from people and let the government spend it. Now there's a reaction to that and people are beginning to say, "Wait just a minute. We're not afflicted as much as we were by depression. We're now afflicted by inflation, and we'd like for you to get it under control." Now you can do that in another way and that without reducing the money supply radically. I think the Joint Economic Committee has recommended that we do it gradually. But the way that you can do it is to reduce

taxes and the impact of government, that is, the weight of government, and increase private savings, so that the private savings can finance some of the debt that you have. FRIEDMAN: There is no way you can do it without reducing, in my opinion, the rate of monetary growth. And I, recognizing the facts, even though they ought not to be that way, I wonder whether you can reduce the rate of monetary growth unless Congress actually does reduce government spending as well as government taxes. BROWN: The problem is that every time we use demand management, we get into

a kind of an iron maiden kind of situation. We twist this way and one of the spikes grabs us here, so we twist that way and a spike over here gets us. And every recession has had higher basic unemployment rates than the previous recession in the last several years, and every inflation has had higher inflation. We've got to get that tilt out of the society. MCKENZIE: Wouldn't it be fair to say, though, that a fundamental difference is the Germans are more deeply fearful of a return to inflation, having had the horrifying experience between the wars,

especially. We tend to be more afraid of recession turning into depression. EMMINGER: I think there is something in it, and in particular in Germany the government would have to fear very much in their electoral prospects if they went into such an election period with a high inflation rate. But there is another important difference. MARTIN: We fear unemployment EMMINGER: You fear unemployment, MARTIN: more than inflation it seems. EMMINGER: but unemployment is feared with us, too, but inflation is just as much feared. But there is another difference; namely, once you have got into that escalating inflation, every

time the base, the plateau, is higher, it's extremely difficult to get out of it. You must avoid getting into that, now that's very cheap advice from me because you are now. (Laughing) EMMINGER: But we have, for the last fifteen, twenty years, always studied foreign experiences, and told ourselves we never must get into this vicious circle. Once you are in, it takes a long time to get out of it. That is what I am preaching now, that we should avoid at all costs to get again into this vicious circle as we had it already in '73-'74.

It took us, also, four years to get out of it, although we were only at eight percent inflation. Four years to get down to three percent. EMMINGER: So you -- McKENZIE: Those were -- yes. EMMINGER: You have, I think, the question whether you can do if in a gradualist way over many, many years, or whether you don't need a sort of shock treatment. SPRINKEL: The film said it took the Japanese - what - four years? FRIEDMAN: Five years. SPRINKEL: Five years. But one of my my greatest concerns is that we haven't suffered enough yet. Most

of the nations that have finally got their inflations - BROWN: Bad election speech. SPRINKEL: -- well, I'm not running for office, Clarence. (Laughter) SPRINKEL: Most countries that finally got their inflation under control had 20, 30 percent or worse inflation. Germany had much worse and the public supports them. We live in a democracy, and we're getting constituencies that gain from inflation. You look at people that own real estate, they've done very well. And how can we get there without going through even more pain, and I doubt that we will. FRIEDMAN: If you ask who are the

constituencies that have benefited most from inflation there are no doubt, it is the homeowners. But it's also the -- it's also the Congressmen who have been able to vote higher spending without having to vote higher taxes. They have in fact – BROWN: That's right. FRIEDMAN: -- Congress has in fact voted for inflation. But you have never had a Congressman on record to that effect. It's the government civil servants who have their own salaries are indexed and tied to inflation.They have a retirement benefit, a retirement pension that's tied to inflation. They qualify, a large fraction of

them, for Social Security as well, which is tied to inflation. So that the beneficial - BROWN: Labor contracts that are BROWN: indexed and many pricing things BROWN: that are tied to it. FRIEDMAN: But the one thing that isn't FRIEDMAN: tied to inflation, and here I want to come back and ask why Congress has been so -- so bad in this area, is our taxes. It has been impossible to get Congress to index the tax system so that you don't have the present effect where every one percent increase in inflation pushes people up into higher brackets

and forces them to pay higher taxes. BROWN: Well, as you know, I'm an advocate of that. FRIEDMAN: I know you are. McKENZIE: Some countries do that, McKENZIE: of course. Canada does that. FRIEDMAN: Oh, of course McKENZIE: Indexes the- BROWN: And I went up to Canada on a BROWN: little weekend seminar program on indexing and came back an advocate of indexing because I found out that the people who are delighted with indexing are the taxpayers. Because as the inflation FRIEDMAN: Absolutley. BROWN: rate goes up their tax level either maintains at the same level or goes down.

The people who are least -- well, the people who are very unhappy with it are the people who have to plan government spending, because it is reducing the amount of money that the government has rather than watching it go up by ten or twelve billion, (you get a little dividend to spend in this country, the bureaucrats do, every year). But the politicians are unhappy with it too, as Dr. Friedman points out because, you see, the politicians don't get to vote a tax reduction, it happens automatically. And so you can't go back and in a praiseworthy

way tell your constituents that I am for you, I voted a tax reduction. And I think we ought to be able to index the tax system so that tax reduction is automatic, rather than have what we've had in the past, and that is an automatic increase in the taxes. And the politicians say, "Well, we're sorry about inflation, but --". FRIEDMAN: Well I want to -- I want to go and make a very different point. I sit here and berate you and you, as government officials, and so on, but I understand very well that the real

culprits are not the politicians, are not the central bankers, but it's I and my fellow citizens. I always say to people when I talk about this, "If you want to know who's responsible for inflation, look in the mirror." It's not because of the way you spend your money. Inflation doesn't arise because you got consumers who are spendthrift; they've always been spendthrift. It doesn't arise because you've got businessmen who are greedy. They've always been greedy. Inflation arises because we as citizens have been asking you as politicians to perform an impossible task. We've been asking you to

spend somebody else's money on us, but not to spend our money on anybody else. BROWN: You don't want us to cut back those dollars for education, right? FRIEDMAN: Right. And, therefore -- FRIEDMAN: well, no, I do. McKENZIE: We've already had a program on that. FRIEDMAN: We've already had a program on that and there's no viewer of these programs who will be in any doubt about my position on that. But the public at large has not- and this is where we come to the political will that Dr. Emminger quite properly talked about. It is -- everybody

talks against inflation, but what he means is that he wants the prices of the things he sells to go up and the prices of the things he buys to go down. But, sooner or later, we come to the point where it will be politically profitable to end inflation. This is the point that - SPRINKEL: Yes. FRIEDMAN: -- I think you were making. SPRINKEL: The suffering idea. FRIEDMAN: Where do you think the -- you know, what do you think the rate of inflation has to be, and judged by the the experience of other countries, before we

will be in that position and when do you think that will happen? SPRINKEL: Well, the evidence says it's got to be over 20 percent. Now you would think we could learn from others rather than have to repeat mistakes. FRIEDMAN: Apparently nobody can learn from history. SPRINKEL: But at the present time we're going toward higher and not lower inflation. MCKENZIE: You said earlier, if you want to see who causes inflation look in the mirror. FRIEDMAN: Right. MCKENZIE: Now, for everybody watching and taking part in this, there must be some moral to that. What does need --

what has to be the change of attitude of the man in the mirror you're looking at before we can effectively implement what you call a tough policy, that takes courage? FRIEDMAN: I think that the man in the mirror has to come to recognize that inflation is the most destructive disease known to modern society. There is nothing which will destroy a society so thoroughly and so fully as letting inflation run riot. He must come to recognize that he doesn't have any good choices. That there are no easy answers. That once you get in this situation where

the economy is sick of this insidious disease, there's gonna be no miracle drug which will enable him to be well tomorrow. That the only choices he has, do I go through a tough period for four or five years of relatively high unemployment, relatively low growth, or do I try to push it off by taking some more of the hair of the dog that bit me and get around it now at the cost of still higher unemployment, as Clarence Brown said, later on. The only choice this country faces is: whether we have temporary unemployment for a

short period, as a side effect of curing inflation or whether we go into a period of still higher unemployment later on and have it to do all over again. That's the only choice we face. And when the public at large recognizes that, they will then elect people to Congress, a president to office who is committed to less government spending and to less government printing of money and until that happens we will not cure inflation. BROWN: But, Dr. Friedman, let me - (Applause) BROWN: Let me differ with you to this extent. I think it is important

that at the time you are trying to get inflation out of the economy that you also give the man in the street, the common man, the opportunity to have a little bit more of his own resources to spend. And if you can reduce his taxes at that time and then reduce government in that process, you give him his money to spend rather than having him yield up all that money to government. If you cut his taxes in a way to encourage it, to putting that money into savings, you can encourage the additional savings in a

private sense to finance the debt that you have to carry, and you can also encourage the stimulation of growth in the society; that is, the investment into the capital improvements of modernization of plant, make the U.S. more competitive with other countries. And we can try to do it without as much painful unemployment as we can get by with. Don't you think that has some merit? FRIEDMAN: The only way -- FRIEDMAN: I am all in favor, as you know of cutting government spending. I am all in favor of getting rid of the counterproductive government regulation that

reduces productivity and disrupts investment. But - BROWN: And we do that, we can cut BROWN: taxes some, can we not? FRIEDMAN: We should -- taxes -- but you are introducing a confusion that has confused the American people. And that is the confusion between spending and taxes. The real tax on the American people is not what you label taxes. It's total spending. If congress spends fifty billion dollars more than it takes in, if government spends fifty billion dollars, who do you suppose pays that fifty billion dollars? BROWN: Of course, of course. FRIEDMAN: The Arab Sheiks aren't

paying it. Santa Claus isn't paying it. The Tooth Fairy isn't paying it. You and I as taxpayers are paying it indirectly through hidden taxation. And therefore the crucial thing is to cut down total government spending, from the point of view of inflation. From the point of view of productivity, some of the other measures you were talking about are far more important. BROWN: But if you concede that BROWN: inflation and taxes are both part and parcel of the same thing, and if you cut spending - FRIEDMAN: They're not part and parcel FRIEDMAN: of the same thing.

BROWN: If you cut spending you -- well, but, you take the money from them in one way or another. The average citizen. FRIEDMAN: Absolutely. BROWN: To finance the growth of government. FRIEDMAN: That's right. BROWN: So if you cut back the size of government, you can cut both their inflation and their taxes. FRIEDMAN: That's right. BROWN: If you – FRIEDMAN: I am all in favor of that. BROWN: All right. FRIEDMAN: All I am saying is: Don't kid yourself into thinking that there is some painless way to do it. There just is not. BROWN: One other way

is productivity. If you can -- if you can increase production, then the impact of inflation is less because you have more goods chasing - FRIEDMAN: Absolutely, but you have to have a sense of proportion. From the point of view of the real income of the American people, nothing is more important than increasing productivity. But from the point of view of inflation, it's a bit actor. It would be a miracle if we could raise our productivity from three to five percent a year, that would reduce inflation by two BROWN: No question, it won't happen FRIEDMAN: percent.

BROWN: overnight, but it's part of the -- it's part of a long range squeezing out of inflation. FRIEDMAN: There is only one way to ease the -- in my opinion there is only one way to ease the pains of curing inflation and that way is not available. That way is to make it credible to the American people that you are really going to follow the policy you say you're going to follow. Unfortunately I don't see any way we can do that. (Several people talking at once.) EMMINGER: Professor Friedman, that's exactly the point which I wanted

to illustrate by our own experience. We also had to squeeze out inflation and there was a painful time of one-and-a-half years, but after that we had a continuous lowering of the inflation rate with a slow upward movement in the economy since 1975. Year-by-year, inflation went down, and we had a moderate growth rate which has led us now to full employment. FRIEDMAN: That's what - EMMINGER: So you can shorten this period by just this credibility and by a consensus you must have, also, with the trade unions, with the whole population, that they acknowledge that policy and

also play their part in it. Then the pains will be much less. SPRINKEL: You see in our case, expectations are that inflation's going to get worse because it always has. This means we must disappoint in a very painful way those expectations, and it's likely to take longer, at least the first time around. Now our real problem has not been that we haven't tried. We have tried and brought inflation down. Our real problem was, we didn't stick to it. And then you have it all to do over. BROWN: Well I would -- BROWN: I would concede

that psychology plays a great, perhaps even the major part, but I do believe that if you have private savings stimulated by your tax system, rather than discouraged by your tax system, you can finance some of that public debt by private savings rather than by inflation, and the result will be to ease to some degree the pain of that heavy unemployment that you seem to suggest is the only only way to deal with the problem. FRIEDMAN: The talk is fine, but the problem is that it's used to evade the key issue: How do you make it

credible to the public that you are really going to stick to a policy? Four times we've tried it, and four times we've stopped before we've run the course. (Several people talking at once.) MCKENZIE: There we leave the matter for tonight, and next week's concluding program in this series is not to be missed. (Applause) MCKENZIE: From Harper Library, good-bye.

Related Videos

57:48

Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 10 How to Stay ...

Free To Choose Network

95,648 views

57:39

Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 04 From Cradle ...

Free To Choose Network

103,840 views

46:28

Milton Friedman on Donahue #2

EdChoice

1,547,682 views

2:28:47

The Savings Expert: Are You Under 45? You ...

The Diary Of A CEO

1,829,018 views

1:26:04

Milton Friedman Speaks: Money and Inflatio...

Free To Choose Network

1,294,875 views

57:43

Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 08 Who Protects...

Free To Choose Network

67,117 views

55:10

How Money Became Worthless | End Of The Ro...

Journeyman Pictures

174,220 views

1:42:54

System Of Money | Creation of Money | Mone...

Moconomy

104,849 views

45:28

Milton Friedman on Donahue - 1979

EdChoice

959,899 views

57:09

Free To Choose - Milton Friedman on The We...

Reelblack One

970,216 views

42:24

Ray Dalio Explaining Principles of Investing

Liwa Capital Advisors

459,640 views

57:54

Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 05 Created Equa...

Free To Choose Network

108,382 views

53:19

Money, Power and Wall Street, Part One (fu...

FRONTLINE PBS | Official

6,375,553 views

25:34

TAKE IT TO THE LIMITS: Milton Friedman on ...

Hoover Institution

1,447,310 views

52:46

Milton Friedman Speaks: Myths That Conceal...

Free To Choose Network

1,627,433 views

1:18:55

Milton Friedman Speaks: Free Trade: Produc...

Free To Choose Network

63,279 views

57:48

Free To Choose 1980 - Vol. 01 The Power of...

Free To Choose Network

315,491 views

33:39

Yanis Varoufakis on the death of capitalis...

Channel 4 News

887,836 views

55:36

End of the Road: How Money Became Worthless

Best Documentary

2,633,819 views

1:26:41

Uncovering HSBC's Dark Financial Empire: T...

Real Stories

1,477,229 views