Why Monkeys Can Only Count To Four

1.04M views936 WordsCopy TextShare

MinuteEarth

To try everything Brilliant has to offer for free for a full 30 days, visit https://brilliant.org/mi...

Video Transcript:

This video is sponsored by Brilliant. More about them at the end of the video. There’s an island in the Caribbean where I used to perform magic tricks for monkeys.

Hi, I’m David, and this is MinuteEarth. I was working on a big study about how animal brains work, and as part of that research, I carried around a big bag of props. Whenever I found a monkey hanging out by itself, I’d bring out this stage – basically a platform that I’d then hide from the monkey’s view with a big piece of posterboard.

I’d take an apple out of the bag and dramatically lower it behind the posterboard, then I’d take out a second apple and then a third. Finally, with a flourish, I’d remove the posterboard, revealing the apples to the monkey. Usually, there would be three apples there but occasionally – thanks to a hidden chamber where I could stash or retrieve an apple – the number of apples on the platform wouldn’t match the number of apples I’d removed from the bag.

When those mismatches happened, the monkeys would stare as if they were surprised – or had even been tricked – which was super cool because it suggests that they have the ability to count. And monkeys aren’t alone. Over the past few decades, using similar sleight-of-hand experiments, magicians – I mean, researchers – have found that pretty much every animal we can test – from spiders to sea lions – seems to get surprised when the number of items they expect to see doesn’t match the number of items that are revealed.

At least that’s what happens when the illusion is performed with numbers smaller than four. But if I lowered, say, four apples during the trick and revealed five apples, the monkeys didn't seem surprised at all; nor would any other species of animal that scientists have tested. This suggests that maybe non-human animals can’t count any higher than four.

But that’s not exactly right. Because while monkeys aren’t surprised when they see four apples get lowered and five get revealed, they are surprised when four apples get lowered and six are revealed, or when nine apples get lowered and twelve get revealed. What the monkeys actually seem to be doing is comparing the relative sizes of two sets of stuff.

One set is the amount of stuff they see go behind the posterboard and the other set is the amount of stuff they see get revealed. So if they expect there to be a pile of apples that looks like this, and instead they see a pile that looks like this, that relative difference is big enough for them to notice, but if they expect a pile that looks like this and instead they see a pile that looks like this, that relative difference seems to be small enough that they don’t seem to notice. Why do animals do this relative comparison, though, instead of just, you know, counting stuff?

Well, when there's a very small amount of something important out there – like, say, yummy apples, or scary predators – it makes sense for an animal to be able to discern small differences between amounts. But when there are lots of things out there, knowing the exact number isn’t as important – it’s more about knowing when the amounts are different enough to matter. And “different enough” to an animal, seems to be a difference greater than 25% – more or less.

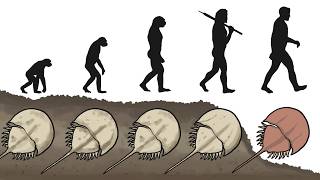

Being able to specifically count numbers of things may just be a waste of energy and brainpower in most situations. Humans – with our super-ability to count and differentiate specific numbers – are actually the weird ones. This skill seems to be unlocked by language, which allows us to give a name to every single individual number, and thus seems to move our counting ability out of the parts of the brain that are used to generally compare set sizes and into a special highly-developed part of the brain that's devoted to more complicated computation.

That’s why, when I repeated my magic show with adult humans, they were of course surprised, even when I did the trick with bigger numbers. But – to show how important language is – when I did the show for preverbal humans – you know, toddlers – they reacted the exact same way the monkeys did – they weren't surprised by small differences between big numbers, but they were very impressed when three apples magically became two! Well, not exactly – they didn’t seem to care much about apples.

I had to trick them with something they cared more about: stuffed animals. Language, though isn't everything when it comes to computation; you also have to develop that part of your brain devoted to math-ing. And Brilliant is where you learn by doing, with thousands of interactive lessons in data analysis, math, programming, and AI.

Brilliant helps you build real skills through hands-on problem-solving based on lessons created by MIT and CalTech professors. And Brilliant just launched a ton of new data courses, all of which use real-world data to train you to see trends and make better-informed decisions. I’m currently making my way through their new course on exploring data visually, where I’m learning how to parse and visualize not just large quantities, but massive datasets in order to make them easier to interpret.

To try everything Brilliant has to offer for free for a full 30 days, visit brilliant. org/MinuteEarth or click on the link in the description. You’ll also get 20% off an annual premium subscription.

Thanks Brilliant.

Related Videos

7:05

Why Don't We Eat Carnivores?

MinuteEarth

3,184,964 views

23:34

Why Democracy Is Mathematically Impossible

Veritasium

5,923,935 views

13:08

We Fell For The Oldest Lie On The Internet

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell

5,972,537 views

4:13

The Species That Broke Evolution?

MinuteEarth

468,845 views

6:42

The Trouble With Tumbleweed

CGP Grey

12,034,787 views

4:01

Which Will Kill You First?

MinuteEarth

956,486 views

8:12

Why Can’t We Make New Stradivari Violins?

SciShow

3,374,038 views

9:27

Hexagons are the Bestagons

CGP Grey

15,651,384 views

4:22

Why There Are No King Bees

MinuteEarth

3,595,707 views

13:17

Simulating the Evolution of Aggression

Primer

23,934,002 views

3:22

The WEIRD Way Monkeys Got to America

MinuteEarth

1,561,511 views

8:12

How We Domesticated Cats (Twice)

PBS Eons

12,147,885 views

17:01

The rarest move in chess

Paralogical

2,734,886 views

15:53

What Actual Aliens Might Look Like

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell

4,865,689 views

13:02

These Survival Myths Could Actually Get Yo...

Debunked

1,583,469 views

7:47

What if the World turned to Gold? - The Go...

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell

14,716,654 views

21:56

A Solid 20 Minutes of Useless Information

AustinMcConnell

7,429,069 views

4:43

Why Do People Hate Koalas? (ft. @tibees )

MinuteEarth

1,178,523 views

32:22

Simulating the Evolution of Aging

Primer

806,843 views

4:55

The Truth About Petri Dishes 🧫

MinuteEarth

426,058 views